article

- Plenty of clear and specific examples of notes of all sorts. People often ask ‘but what should a note look like?’ Here’s the answer, visually.

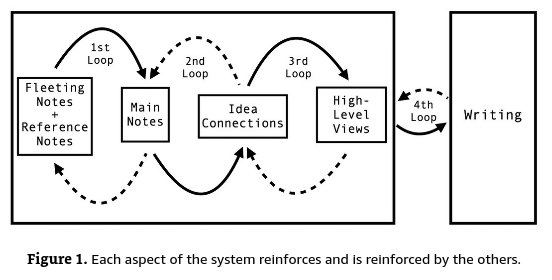

- Many helpful workflow diagrams. People also ask ‘how does the system operate as a whole?’ This book shows exactly how the Zettelkasten process works, and in what order.

- Clear references both to Niklas Luhmann’s process and to other relevant predecessors. If you want to refer back to the sources, there is a wealth of pointers here.

- At the end of each chapter, a checklist of specific activities to try, to implement the ideas just covered: what to do, what to remember and what to watch out for. If you’re wondering exactly what to do next with your notes, this book shows you (also, what not to do, especially in ch. 7).

- Helpful writing advice, which shows how to use your Zettelkasten to produce four different kinds of material: short-short items (i.e. social media posts), blog posts, articles and books.

- Overall, a clear, step-by-step, repeatable writing process to follow, from capturing your thoughts (ch. 1) right through to managing your writing workflow (ch. 9).

- What is the real work of serendipity?

- A library of good neighbours

- The Dewey Decimal System pigeonholes all knowledge, like cells in a prison

- Harrison Owen, creator of Open Space Technology.

-

Don’t build a magnificent but useless encyclopaedia

-

Document your journey through the deep forest

-

Avoid inert ideas

-

Converse about what really matters to you

-

Imagine, then build, new knowledge products

-

Where (and how) you go is more important than where you start from

-

An example

- Maureen Murdock (1990) and later Gail Carriger (2020) have both presented feminised versions of the heroic quest narrative. I’m not convinced that these heroine’s journeys are really all that different, though, since they still assume that heroism, albeit that of women, is where it’s at. At least there’s an attempt to re-balance the faulty idea that only men are at the centre.

- The New Yorker published a moving non-fiction account by Laura Secor of an Iranian woman’s bravery. The true story of journalist Asieh Amini doesn’t rely on a standard heroic arc, yet is highly effective. This is only one example of very many alternatives.

- Novelist Becky Chambers points out in a talk on YouTube that real life has no protagonists. Surely this can help us to question stale narrative forms, especially those which claim to be true to reality.

- Meanwhile, Christina de la Rocha is on a noble quest to put an end to the hero’s journey in literature and beyond. OK, not a quest. Perhaps she’d approve of Ursula le Guin’s claim that “the novel is a fundamentally unheroic kind of story”. More on that in a moment.

- Screenwriter Anthony Mullins has written a whole book showing that there’s plenty more than only one kind of character arc.

-

See also Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1994) on women’s role in technology, textiles and the string revolution. ↩︎

-

If you’re not sure what website feeds are, see IndieWeb: feed reader and how to use RSS feeds. ↩︎

-

Does the index box distort the facts?

-

Can you create coherent writing just from a pile of notes?

-

Perhaps you should keep your notes private

-

Make it flow

-

To create coherent writing, make coherent notes

-

Begin with fragments

-

From smaller parts build a greater whole

-

Join your work together

-

Do it seamlessly well

- If you’ve enjoyed it so far, you can just keep doing what you’ve been doing, collecting all the things. Why not?

- But if you like, you could start doing it more deliberately. For example, at the start of a new year, you could say to yourself: In 2023 I seem to have been interested in a,b, and c. Now in 2024 I want to explore more about b, drop a, and learn about d and e.

- How to be interested in everything

- Don’t you need to start with categories?

- It’s tempting to place your notes in fixed categories

- To build something big start with small fragments

- Thoughts are nest-eggs: Thoreau on writing

- This article is adapted from a comment on Reddit

-

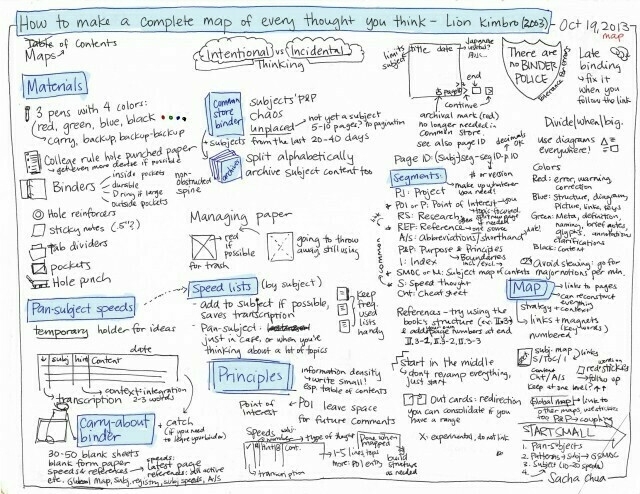

There are exceptions. A few people have tried to video their whole lives. And at least one person, Lion Kimbro, has tried to write down all their thoughts. But its not sustainable. ↩︎

-

Which way is up?

-

Try seeing the trees and the forest too

-

Hierarchy, heterarchy, homoarchy… am I just making these words up?

-

Get linking to get thinking

-

The key questions

-

What if I really just want a fixed structure?

A System for Writing by Bob Doto

“The note you just took has yet to realize its potential.” - Bob Doto

Another ‘Zettelkasten primer’ won’t be needed for some time, since this one is direct, concise, thorough and strongly practical.

📚A System for Writing by Bob Doto is out!

If you’ve become confused or cynical watching those endless videos in which an influencer who discovered the Zettelkasten five minutes ago is suddenly the expert; or if you’ve read Sönke Ahrens' book, How to Take Smart Notes and thought “now I know why I should make notes but I still don’t really know how”, well here’s the antidote: the only Zettelkasten book you’ll ever need.

My paperback copy of A System for Writing arrived just in time for weekend reading. It’s a deliberately useful book, with a clear three-part structure. It gets to the point quickly and stays there: how to write notes, how to connect them and how to use this system to produce finished written work.

Things I especially appreciate in A System for Writing:

Will anyone be disappointed? Well, if you’re only looking for a manual on a particular piece of software, this book won’t satisfy you. It tells almost nothing about whatever the popular app-of-the-day is. You are not going to be told here whether Obsidian is better than Obshmidian. Software comes and goes, while the underlying principles of the Zettelkasten approach, as presented here, can be applied in many different contexts.

What about those who aren’t all that interested in actually publishing anything, who instead just want their notes to help them remember stuff, perhaps for tests? Well, although this book focuses without apology on writing, it will still be really useful for anyone making notes as a ‘second memory’ (Luhmann’s term) because by reading this (especially the first two parts) they’ll soon be making clearer, more concise and more accessible notes, whatever they intend to use them for.

And what of those who have absolutely no interest in obscure terms like ‘Zettelkasten’, who recoil from any kind of dubious productivity fetish, and just want to get things written? This is where the book excels and where it really comes good on the promise of its title. Yes, this is a system for writing. The author, who has himself written several books, shows from his direct experience how an effective note-making practice can lead to a more natural, unforced, effective and consistent writing practice. The Zettelkasten as presented here is an approach to note-making that will simply aid writing, without wasting time or effort.

This has certainly been my experience. Before I implemented my own Zettelkasten approach I was struggling both with organising my notes and with producing coherent writing. Since then, it’s been a different story. But until now there hasn’t been a Zettelkasten guidebook I’d wholeheartedly recommend to others. Now there certainly is.

So if you want to learn quickly how to capture your ideas effectively and write productively, stress-free, then get hold of A System for Writing right now.

More about Bob Doto.

Read about the illusion of integrated thought, which is cited in chapter 7 of the book.

My take on starting a Zettelkasten: How to make a Zettelkasten from your existing deep experience.

Something from nothing is no fairy tale

As an adult, one of my favourite fairy tales is Puss in Boots.

I have immense respect for this talking cat. He has nothing going for him - not even a decent pair of shoes. And to make matters worse he finds himself lumbered with a pretty mediocre human owner.

Folklore academics have a way of classifying the tales they study. It’s called the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index (ATU). And in this index, Puss in Boots is Type 545: the cat as helper.

That’s completely wrong.

Read it for yourself. This story is not about the frankly lacklustre youngest son of the mill. No, it’s about the cat, a cat who has almost no help, who has to do practically everything himself, and who never gives up until finally he gets what he needs.

The great writer Angela Carter would have agreed with this. She observed the cat was “the servant so much the master already“[^1]. But this is hardly controversial. Perrault’s version of the story actually has the title “The Master Cat“.

So as you probably remember, the tale begins when the cat experiences an unexpected disaster. The old miller dies, leaving the mill to his eldest son.

But the mill’s cat he leaves to the youngest son.

Not only is the cat suddenly homeless, but to make things even worse his fate is now shackled to a penniless human without prospects.

So what’s a homeless cat to do?

Why not let your reading be a smorgasbord of serendipity?

Yes indeed, why not let your reading be a smorgasbord of serendipity?

Here’s Anna Funder, author of Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life, on working at the University of Melbourne English Department library as a student:

“It sounds prehistoric now, but I sat at the front desk, typing out index cards for new acquisitions or requests from staff for books or journals — anything from the latest novel, to psychoanalysis, poetry or medieval studies. I read things that had nothing to do with my studies: a smorgasbord of serendipity. Despite my time there, I have never understood the Dewey decimal system: how can numbers tell you what a book is, to a decimal point?” - Every book you could want and many more

My take on this?

HEAJ:Mundaneum by Marc Wathieu is licensed under CC BY 2.0

A minimal approach to making notes

I want a minimal approach to making notes.

I don’t want anything fancy, just enough structure to be useful.

When I see people’s souped-up Obsidian note-taking vaults my head spins (OK, I’m jealous). I also wonder, though, what extra result is achieved with a fantastically complex system. Having said that, I’m keen on people creating a working environment that works for them, and I do admire people’s creativity in this area.

I just can’t be bothered to do it myself.

When discussing the Zettelkasten approach to making notes, it seems there are a lot of different note types to consider, which confuses people. The extensive discussion about different types of notes caused by reading Sonke Ahrens’s book How to Take Smart Notes makes me think this multiple-note-types approach is just too complicated for me. So what do I do instead?

A forest of evergreen notes

Jon M Sterling, a computer scientist at Cambridge University, has created his own ‘mathematical Zettelkasten’, which he also calls ‘a forest of evergreen notes’.

He maintains a very interesting website, built using a tool he created, named, appropriately enough, Forester.

The implementation of his ideas raises all sorts of ideas and questions for me, almost all enthusiastic. Here are a few in no order at all:

Make your notes a creative working environment

“Do you have an ideal creative environment? Also do you believe the physical space influences your creativity?”

This is a question Manuel Moreale regularly asks his guests on the People and Blogs newsletter. The answers are always fascinating and well worth a read.

This got me thinking about my own working environment and maybe I overthought it. It looks like I’ve totally ignored Barry Hess’s reminder that you’re a blogger not an essayist.[^1] Anyway, here goes.

Note: This post is part of the Indieweb Carnival on creative environments.

Is the Web reconfiguring itself again?

Is the web falling apart?, Eric Gregorich wonders.

Meanwhile Manuel Moreale is confident that the web is not dying.

I agree with both of them. These views aren’t contradictory. Falling apart is what the Web does best. It’s been falling apart since it started, and reconfiguring itself too.

Google search used to control and shape the web. Because everyone just Googled their searches, websites all used Search Engine Optimization in a vicious circle of conformity. But that’s finally changing.

Search gets degraded by advertising greed on one side and AI tools are generating drivel on the other. Both are examples of what Ed Zitron calls the rot economy.

So how can good material rise to the surface?

In part it’s a return to the old ways. Blogrolls and webrings and RSS are having a mini-revival and it’s not entirely mere nostalgia. One-person search engines like Marginalia are having a moment, as are metasearch engines and other ‘folk’ search strategies. I like little experiments like A Website Is A Room.

Here’s my tip: to find interesting books, great quotes, and intriguing podcasts, more people should know about micro.blog Discover!

Photo by Valeria Hutter on Unsplash

How to set your own agenda

Harrison Owen, who died in March 2024, invented one of the most hopeful approaches to group facilitation I’ve ever come across. He called it ‘Open Space Technology’ (OST), but it was far from hi-tech. In fact, the main ‘technology’ was simply in how people in a group setting can interact fruitfully with one another, even when they really don’t agree.

“Peace of the sort that brings wholeness, harmony, and health to our lives only happens when chaos, confusion, and conflict are included and transcended.”

I first came across Open Space as a means of organising workshops in highly contested political spaces.

In the UK during the 1980s and early 1990s progressive social activity was constantly undermined by Trotskyites (or whatever they were) striving to co-opt social movements for their own ends. There was always a risk that as soon as you set up a committee of any kind, they’d get themselves voted onto it and turn it into a front for the true workers revolutionary communist workers party, or some such combination of those terms.

But what were the alternatives? The Labour Party had been hammered with this problem, and had settled on a full-blown witch hunt against anyone affiliated with the Militant Tendency, which like a monstrous baby cuckoo had nearly pushed them out of their own nest. We’d witnessed how the so-called cure was nearly as bad as the disease.

I think it was about 1992 when we organised our own small Open Space event. Of course, the entryists turned up, but the Law of Two Feet really stumped them. When they realised anyone could set the agenda they were delighted. This must have seemed much easier than having to take over by stealth! But when the discussions began they were confounded by the fact that, equally, anyone could just walk away and find something more important to them. To everyone except the entryists, the experience was delightful.

Image by Chris Kinkel from Pixabay

Of course, OST didn’t change the whole world, and it’s not useful for every meeting. But it was formative for me personally, because I could see how people could come together to identify, commit to and begin to solve their own problems, without waiting for someone else to do it for them.

Open Space Technology has also left a strong mark on facilitation generally. Unconferences, World Café, Bar Camp, the Art of Hosting, design sprints, and many other approaches owe a great deal to Harrison Owen’s pioneering determination to trust people to pursue their own agendas.

Vale Harrison Owen.

More:

Working in Open Space: A Guided Tour

Don't make a Zitatsalat out of your writing

Zitatsalat? What does that even mean?

Yes, Zitatsalat. I found this lovely but rarely used German term in the title of a book by the journalist Stephan Maus. The book’s name is Zitatsalat von Hinz & Kunz.[^1]

I love the rhyming rhythm of this compound term, but what does Zitatsalat actually mean?

Well, Zitatsalat translates as Quote Salad. It’s not a compliment.

Zitatsalat, by Stephan Maus (2002).

But what’s wrong with quoting other writers?

How to make Mastodon even more fun!

Here are a couple of fun websites that will make Mastodon (and possibly the whole fediverse) even more fun. I know, it hardly seems possible. And if you know of others, please let me know about them too.

Just my toots

Do you sometimes wish you could see all your posts on Mastodon in a long list with no distractions? Of course you do! Every day! That’s why justmytoots.com is here to help. And yes, it shows you just your toots.

For the record, I hate the word ‘toots’.

At least where I live no one thinks of flatulence when they hear it, but still, it somehow manages to sound even more stupid than ‘tweets’, which takes some doing.

Now, above the cacophony of all the tooting I can almost hear you ask, “What’s the alternative?” ‘Posts’, that’s the alternative, and that’s what I’m sticking with. Why not join me, world?

Until then, you can see just my toots at https://justmytoots.com/@writingslowly@aus.social

RSS is dead LOL

Now this one really is cool.

You know how everyone at the Internet always says ‘RSS is dead’, right? It’s so annoying!

But anyway, just type in a fediverse username into rss-is-dead.lol and up pops a list of RSS feeds for that user and every account that account follows.

Its amazing! Nearly everyone I follow has an RSS feed! Wow!

Pretty much proves RSS still ain’t dead. Take that, haters!

Bonus fact: it turns out you can use RSS to ‘boost your productivity’. I don’t know what that phrase means, but it sounds great!

Meanwhile, check out my graph, or whatever you call it, at rss-is-dead.lol.

How to start a Zettelkasten from your existing deep experience

An organized collection of notes (a Zettelkasten) can help you make sense of your existing knowledge, and then make better use of it. Make your notes personal and make them relevant. Resist the urge to make them exhaustive.

Yes, we can be heroes, but does that mean we should be?

Yes really, we can be heroes. Thanks very much David Bowie! But if this sounds attractive, perhaps we should be careful what we wish for.

Do you want to be the hero of your own story? Perhaps you already are

According to reporting in Scientific American, imagining yourself as the hero of your own life gives you an increased sense of meaning.

“Our research reveals that the hero’s journey is not just for legends and superheroes. In a recent study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, we show that people who frame their own life as a hero’s journey find more meaning in it”.

But it’s not always great to be a hero

Meanwhile, from a quite different research perspective, comes a warning: Stanley and Kay (2023) caution that making people out to be heroic can inadvertently single them out for poor treatment from their peers.

“our studies show that heroization ultimately promotes worse treatment of the very groups that it is meant to venerate.”

Reading this I immediately thought of all those ‘heroic’ health workers who helped their communities through the COVID crisis at great personal cost and with very little long-term recognition (McAllister et al. 2020). In far too many cases, calling doctors, nurses and hospital workers heroes and even super-heroes ended up as quite tokenistic, little more than a way of justifying the exploitation of their labour. First they make you a hero, then they make you burn out.

Banksy’s artwork of a child playing with a nurse ‘superhero’ doll raised more than 16m for charity… but nurses' pay and conditions didn’t take off

Sometimes heroism isn’t what it seems

And here’s yet another, quite different warning: sometimes the person who sets themselves up as a classic hero is revealed to be anything but that. The case of Australian SAS fighter Ben Roberts-Smith is an extraordinary example of the moral jeopardy of a whole society desperate to believe in heroism. It seems this decorated and celebrated ‘war hero’ was really quite the opposite. The cover-up shows how much people want to believe in heroes, even when they don’t exist. This real-life tale has echoes of Beowulf to it. In Maria Dahvana Headley’s contemporary version (2021), the final words of that centuries-old tale ring painfully, bleakly, hollow with macho delusion:

”He rode hard! He stayed thirsty! He was the man! He was the man.”

So can we journey beyond the ‘hero’s journey’ already?

The hero’s journey trope has become so ubiquitous that it’s sometimes hard to remember that there’s any other kind of story. But there certainly is.

And author Jane Alison goes even further. In her book Meander, Spiral, Explode she notes that there are far more key patterns in literature than just the arc.

Not every story is a journey

Taking her cue from Joseph Frank’s book The idea of spatial form, and from Peter Stevens’s Patterns in Nature, Alison identifies some alternative or complimentary shapes.

I particularly like her concept of the story that meanders like a river, or ripples in waves and wavelets. These aquatic images remind me of something the former monk and psychotherapist Thomas Moore said about how life itself has a kind of liquidity to it:

“Your story is a kind of water, making fluid the brittle events of your life. A story liquefies you, prepares you for more subtle transformations. The tales that emerge from your dark night deconstruct your existence and put you again in the flowing, clear, and cool river of life.” (Moore, 2004, p. 61)

In his book on spatial form, Joseph Frank examines the structure of Djuna Barnes’s modernist novel, Nightwood. This novel doesn’t have a hero’s journey or a flowing river, but instead has a series of views or glimpses of life. He says:

“The eight chapters of Nightwood are like searchlights, probing the darkness each from a different direction, yet ultimately focusing on and illuminating the same entanglement of the human spirit . . . And these chapters are knit together, not by the progress of any action . . . but by the continual reference and cross-reference of images and symbols which must be referred to each other spatially throughout the time-act of reading.”

This searchlight metaphor is illuminating, but story structure can be yet looser, more diffuse than rivers and spotlights. I’m particularly taken with Ursula Le Guin’s carrier bag theory of fiction. Remember she said the novel is a fundamentally unheroic kind of story? If so then what is it?

“the natural, proper, fitting shape of the novel might be that of a sack, a bag. A book holds words. Words hold things. They bear meanings. A novel is a medicine bundle, holding things in a particular, powerful relation to one another and to us.”

Le Guin’s insight is itself based on the carrier bag theory of human evolution, as described in Elizabeth Fisher’s Women’s Creation (1979).

“The first cultural device was probably a recipient …. Many theorizers feel that the earliest cultural inventions must have been a container to hold gathered products and some kind of sling or net carrier.” 1

Not everyone needs to be a hero to be a valid person. Mostly it’s better when we’re not. And not every story needs to be a hero’s journey for it to be worth the telling. The idea of the hero can be useful in some circumstances, dangerous in others. But more often it just gets in the way. Sometimes it’s really about “complex skills and compassion”. Sometimes it’s less about hunting and more about gathering.

So now, do you still want to be a hero, you hero you?

Now read:

More than ever, embracing your humanity is the way forward

References

Alison, Jane. 2019. Meander, Spiral, Explode. Design and Pattern in Narrative. New York: Catapult.

Barber, Elizabeth Wayland. 1994. Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years; Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times. New York, NY: Norton.

Barnes, Djuna. 2006/1937. Nightwood, New York: New Directions.

Carriger, Gail. 2020. The Heroine’s Journey: For Writers, Readers, and Fans of Pop Culture. Gail Carriger LLC.

Fisher, Elizabeth. 1979. Woman’s Creation: Sexual Evolution and the Shaping of Society. 1st ed. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press.

Frank, Joseph. 1991 The Idea of Spatial Form, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Headley, Maria Dahvana. 2021. Beowulf. A New Translation. Melbourne and London: Scribe.

Kaul, Aashish. 2014. Mapping space in fiction: Joseph Frank and the idea of spatial form. 3am Magazine

LeGuin, Kroeber, Ursula. 1989. “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” in Dancing at the Edge of the World. New York: Grove Atlantic Press. Accessed at stillmoving.org/resources…

Margaret McAllister, Donna Lee Brien & Sue Dean (2020) The problem with the superhero narrative during COVID-19, Contemporary Nurse, 56:3, 199-203, DOI: 10.1080/10376178.2020.1827964

Moore, Thomas. 2004. Dark Nights of the Soul. London, UK: Piatkus Books.

Mullins, Anthony. 2021. Beyond the Hero’s Journey: A Screenwriting Guide for When You’ve Got a Different Story to Tell. Sydney, N.S.W: NewSouth Publishing.

Murdock, M. 1990. The Heroine’s Journey. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications.

Rogers, B. A., Chicas, H., Kelly, J. M., Kubin, E., Christian, M. S., Kachanoff, F. J., Berger, J., Puryear, C., McAdams, D. P., & Gray, K. 2023. Seeing your life story as a Hero’s Journey increases meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 125(4), 752–778. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000341

Secor, Laura. 2015. War of Words. New Yorker

Stanley, M. L., & Kay, A. C. 2023. The consequences of heroization for exploitation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000365

Stevens, P. 1974. Patterns in Nature, New York: Little, Brown & Co.

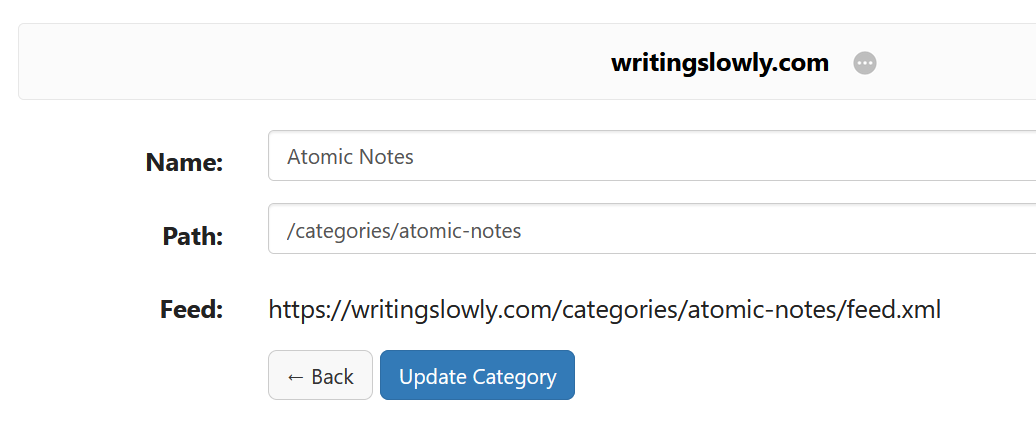

Atomic notes - all in one place

From today there’s a new category in the navigation bar of Writing Slowly.

‘Atomic Notes’ now shows all posts about making notes.

How to make effective notes is a long-standing obsession of mine, but this new category was inspired by Bob Doto, who has his own fantastic resource page: All things Zettelkasten.

The Atomic Notes category is now highlighted on the site navigation bar.

And if you’d like to follow along with your favourite feed reader,there’s also a dedicated RSS feed (in addition to the more general whole-site feed).1

But if there’s a particular key-word you’re looking for here at Writing Slowly, you can use the built-in search.

And if you prefer completely random discovery, the site’s lucky dip feature has you covered.

Connect with me on micro.blog or on Mastodon. And on Reddit, I’m - you guessed it - @atomicnotes.

See also:

Assigning posts to a new category with micro.blog

A new post category in micro.blog, filtered to include existing posts

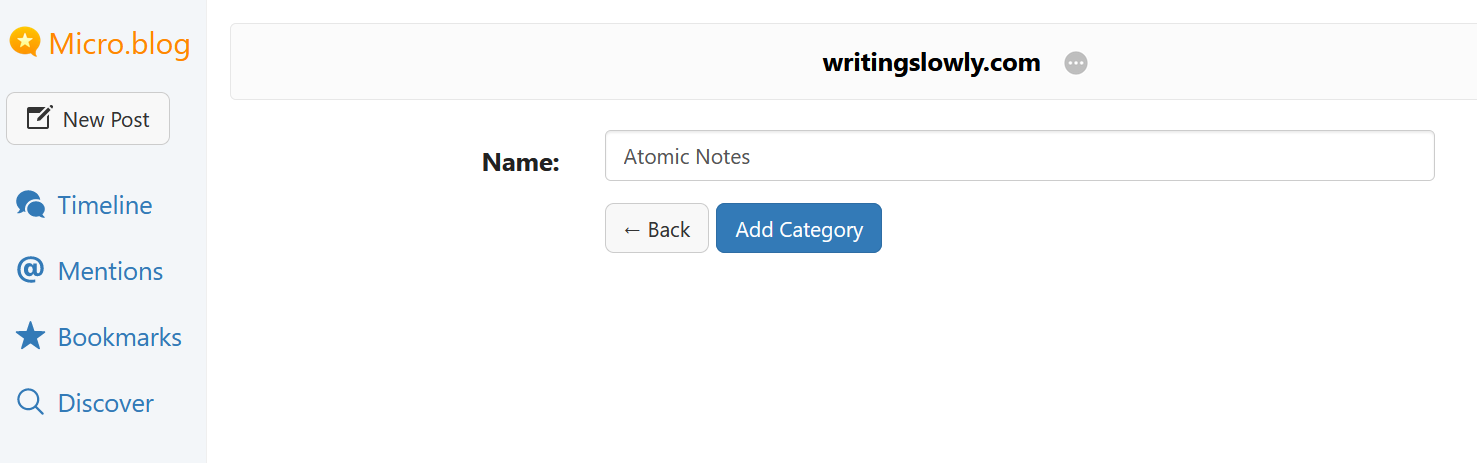

Micro.blog is a really useful and easy way to host a website. Even though it feels more like a cottage industry than a corporation there are way more features (and apps!) than I can probably use. It’s amazing how much Manton Reece, micro.blog’s creator, has achieved.

Under the hood the micro.blog platform is based on the Hugo static site generator, but there are a few differences. One such difference is post categories.

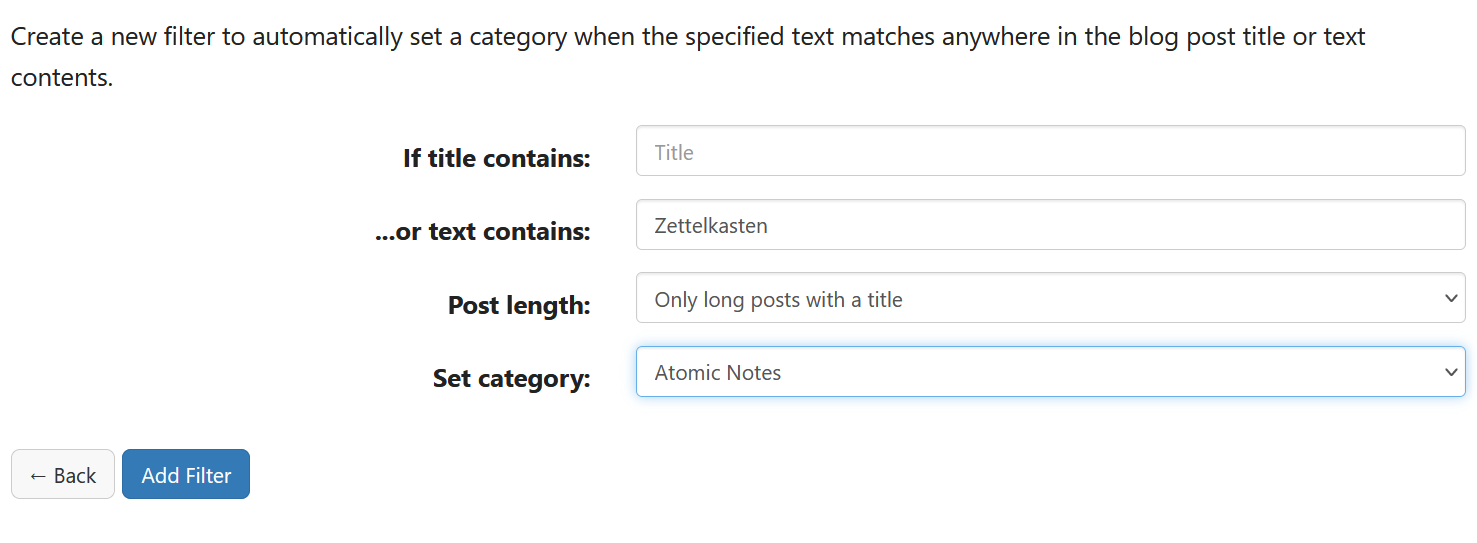

Here’s a new category being created.

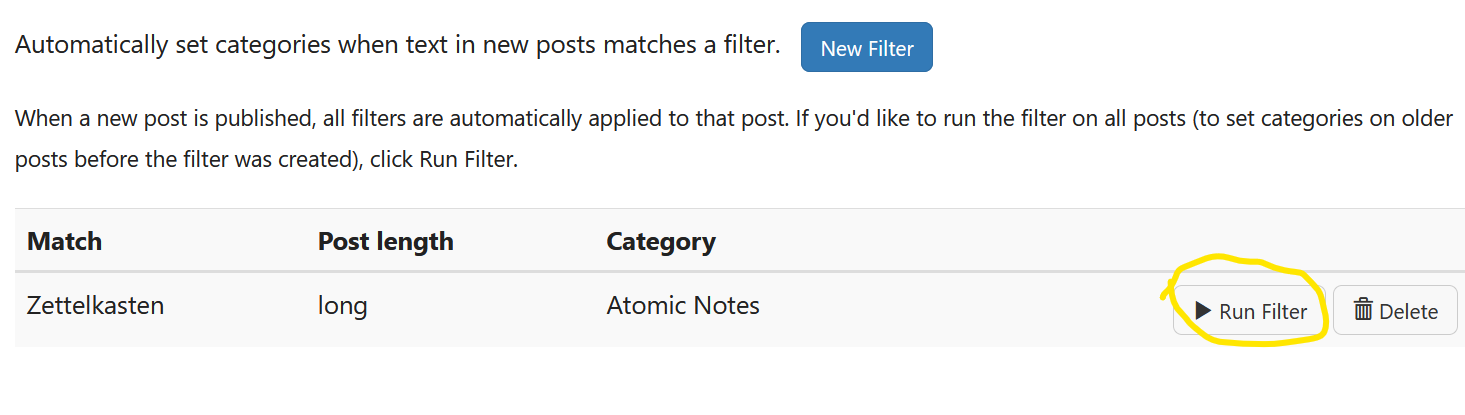

It’s very easy to create a new category of posts, then you can use a filter to automatically add all new posts that include a selected key-word (or emoji, or even html element). By default only new posts are affected. But by running the filter you can also add all previous posts that meet the selected criteria. That’s what I wanted to do.

Once you have a new category, you can add a filter. This particular filter assigns to this new category only long posts with a particular word in the text.

When you run the filter, all existing posts that match will be added to the category. And future posts will be added automatically.

Also, each category gets its own RSS feed, which can be very useful.

This process was much easier than I expected!

More info from elsewhere:

How to overcome Fetzenwissen: the illusion of integrated thought

It’s too easy to produce fragmentary knowledge.

One potential problem associated with making notes according to the Zettelkasten approach is Verknüpfungszwang: the compulsion to find connections. It may be true philosophically that everything’s connected, but in the end what matters is useful or meaningful connections. With your notes, then, you need to make worthwhile, not indiscriminate links.

Another potential problem is Fetzenwissen: fragmentary knowledge, along with the illusion that disjointed fragments can produce integrated thought.

Almost by definition, notes are brief, and I’m an enthusiast of making short, modular, atomic notes. Yes, this results in knowledge presented in fragments. And in their raw form these fragmentary notes are quite different from the kind of coherent prose and well-developed arguments readers usually expect. You can’t just jam together a set of notes and expect them to make an instant essay. So is this fragmentary knowledge really a problem for note-making? If so, how can determined note-makers overcome it?

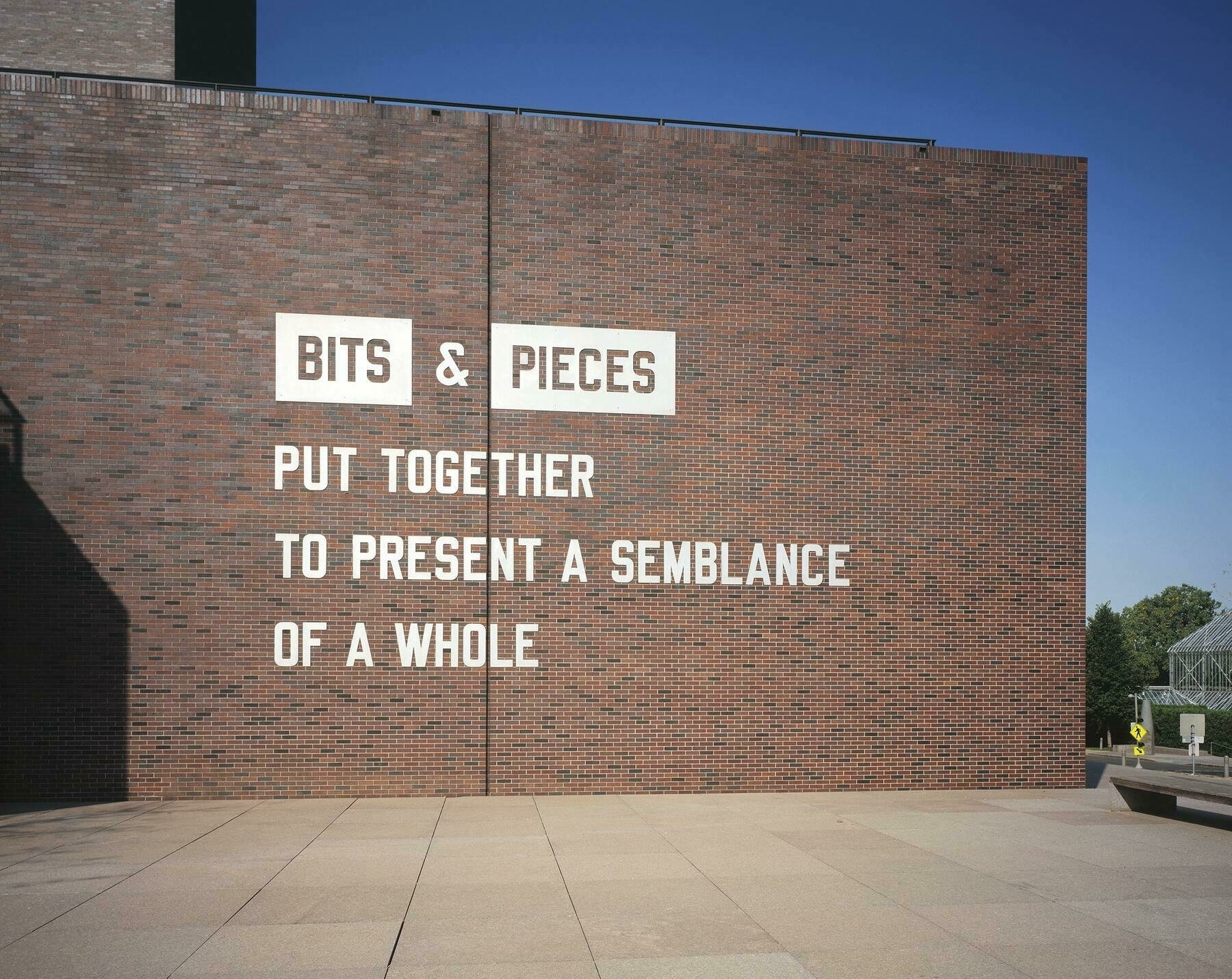

From fragments you can build a greater whole

Everything large and significant began as small and insignificant

This is my working philosophy of creativity and I’m trying to follow it through as best I can. Starting with simple parts is how you go about constructing complex systems.

“A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over, beginning with a working simple system”. — John Gall (1975) Systemantics: How Systems Really Work and How They Fail, p. 71.

Bits and pieces put together to create a semblance of a whole, by Lawrence Weiner

How to decide what to include in your notes

Before the days of computers, people used to collect all sorts of useful information in a commonplace book.

The ancient idea of commonplaces was that you’d have a set of subjects you were interested in. These were the loci - the places - where you’d put your findings. They were called loci communis - common places, in Latin, because it was assumed everyone knew what the right list of subjects was.

But in practice, everyone had their own set of categories and no one really agreed. It was personal.

Since the digital revolution, things have become trickier still. There’s no real storage limit so you could in principle make notes about everything you encounter. But no matter what software you use, your time on this earth is limited, so you need to narrow the field down somehow1.

But how, exactly?

You might consider just letting rip and collecting everything that interests you, as though you’re literally collecting everything.

Lion Kimbro tried to make a map of every thought he had.

As time passes, you’ll notice that you haven’t actually collected everything because that’s completely impossible. Even Thomas Edison, the prolific inventor, wasn’t interested in absolutely everything, although he tried hard to be. If you do a bit of a stock-take of your own notes, you’ll see that, really, you gravitate towards only a few subjects.

These are your very own ‘commonplaces’.

From then on you have two choices.

You could create an index, with a set of keywords, and add page number references to show what subject each entry is about, and how they relate. Or not. Of course, it’s your collection of notes and you can do whatever pleases you. That’s the point.

Bower birds collect everything, but with one crucial principle.

Where I live we have satin bower birds.

The male creates a bower out of twigs and strews the ground with the beautiful things he’s found. Apparently this impresses the females. The bower can contain practically anything, and it really is beautiful. Clothes pegs, pieces of broken pottery, plastic fragments, bread bag ties, lilli pilli fruit, Lego, electrical wiring, string - even drinking straws, as in the photo above. The male bower bird really does collect everything. But what every human notices immediately is that every single item, however unique, is blue.

I enjoy collecting stuff in my Zettelkasten, my collection of notes, but like the bower bird I have a simple filter. I always try to write: “this interests me because…” and if there’s nothing to say, there’s no point in collecting the item. It’s just not blue enough.

See also:

Images:

Sacha Chua Book Summary CC-by-4.0.

Peter Ostergaard, Flickr, CC NC-by 2.0 Deed

At last, writing slowly is back in fashion!

Cal Newport, author of the forthcoming book, 📚Slow Productivity, has finally latched on to the premise of this website: you can get a lot done by writing slowly.

Speeding up in pursuit of fleeting moments of hyper-visibility is not necessarily the path to impact. It’s in slowing down that the real magic happens.

I didn’t even know they could drive.

See also:

Thinking nothing of walking long distances

How far is too far to walk?

Author Charlie Stross observed that British people in the early nineteenth century, prior to train travel, walked a lot further than people today think of as reasonable.

I’ve noticed a couple of literary examples of this seemingly extreme walking behaviour, both of which took place in North Wales.

Headlong Hall

In chapter 7 of Thomas Love Peacock’s satirical novel, 📚Headlong Hall (1816), a group of the main characters takes a morning walk to admire the land drainage scheme around the newly industrial village of Tremadoc, and they walk halfway across Eryri to do so, traversing two valleys and two mountain passes. The main object of their interest is The Cob, a land reclamation project that was later to become a railway causeway. Having seen it, and having taken some refreshment in the village, they walk straight back again.

Image: The Moelwyn range, viewed from the Cob. Wikipedia CC sharealike 2.0

Wild Wales

You’d think the invention of the railways would have put people off walking such long distances, but apparently not so much. In his travel account, 📚Wild Wales (1862), George Borrow walks from Chester 18 miles to Llangollen, then walks another 11 miles to Wrexham just to fetch a book. Interestingly, he was writing after the railways had arrived. He was happy to put his wife and children on the train - but still walk the journey himself.

Real life

I would have believed these feats of everyday walking were improbable, except for the fact that when I was a child, a man in our village, Mr Large, walked every day to and from Chester, a round trip of 26 miles. He didn’t need to do it. He was in his eighties and well retired, and he could just have walked two miles to the bus stop. But apparently you don’t break the habits of a lifetime. Everyone in the village must have offered him a lift at one time or another, but he’d made it known that he preferred to walk. So having observed Mr Large regularly tramping the back lanes with determination, I already knew a long utility walk is more than possible.

These days, people rarely get out of their cars, convinced as they are that progress has been made. Walking is a problem, it seems, not a solution. And yet, on holiday, some people do long walks or even very long walks. For fun.

Oh brave new world that has such people in it!

Does the Zettelkasten have a top and a bottom?

What does it mean to write notes ‘from the bottom up’, instead of ‘from the top down’?

It’s one of the biggest questions people have about getting started with making notes the Zettelkasten way. Don’t you need to start with categories? If not, how will you ever know where to look for stuff? Won’t it all end up in chaos?

Bob Doto answers this question very helpfully, with some clear examples, in What do we mean when we say bottom up?. I especially like this claim:

“The structure of the archive is emergent, building up from the ideas that have been incorporated. It is an anarchic distribution allowing ideas to retain their polysemantic qualities, making them highly connective.”