A channel of the Katsura River at Arashiyama, Kyoto.

Reviewing my photographs really makes me wish I was back in Japan.

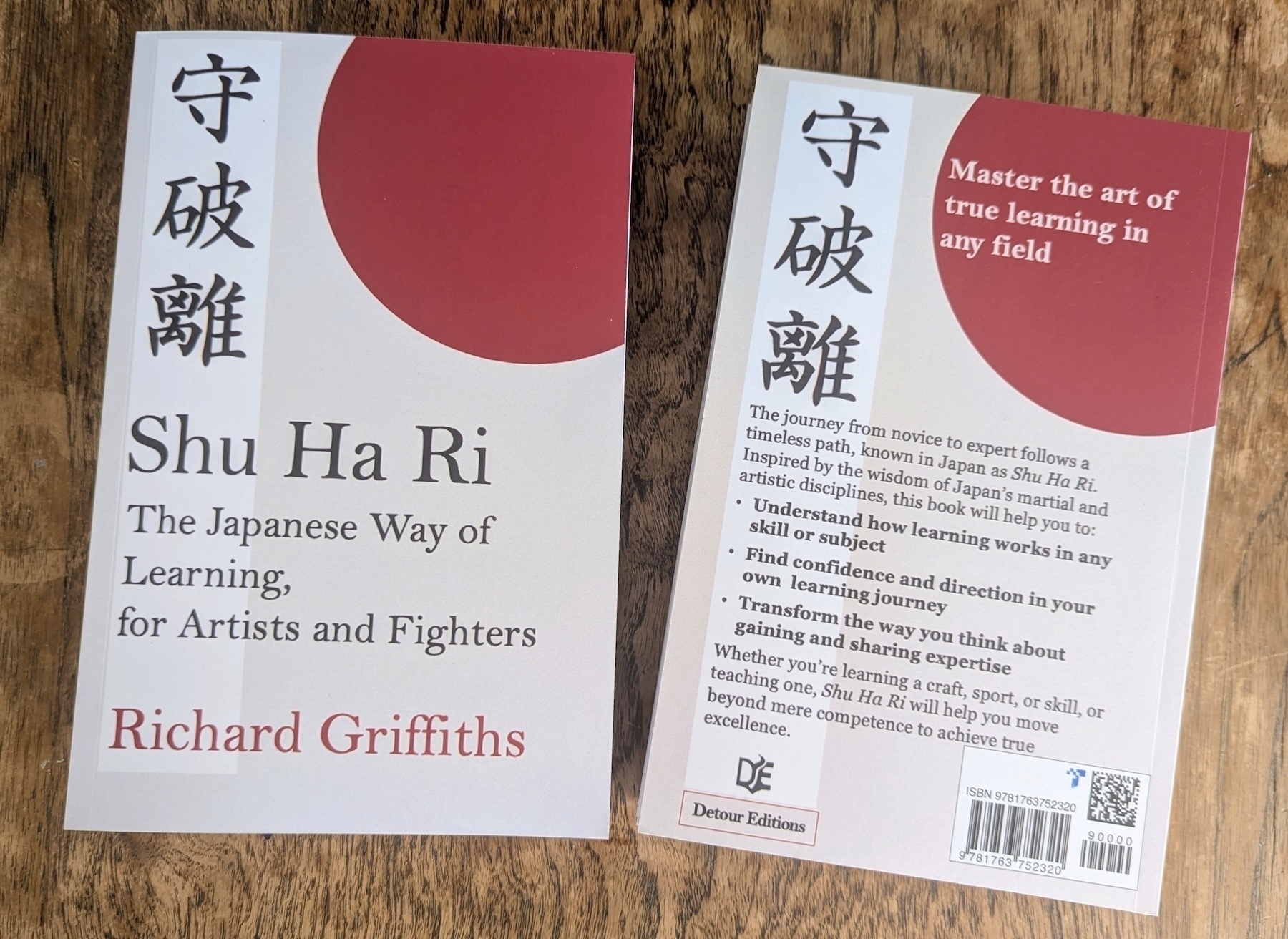

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now.

#Japan #Kyoto #ShuHaRi #JapaneseCulture #JapaneseAesthetics #Photography

The Toe of the Year and the Curious Case of John Donne's Missing Commonplace Book

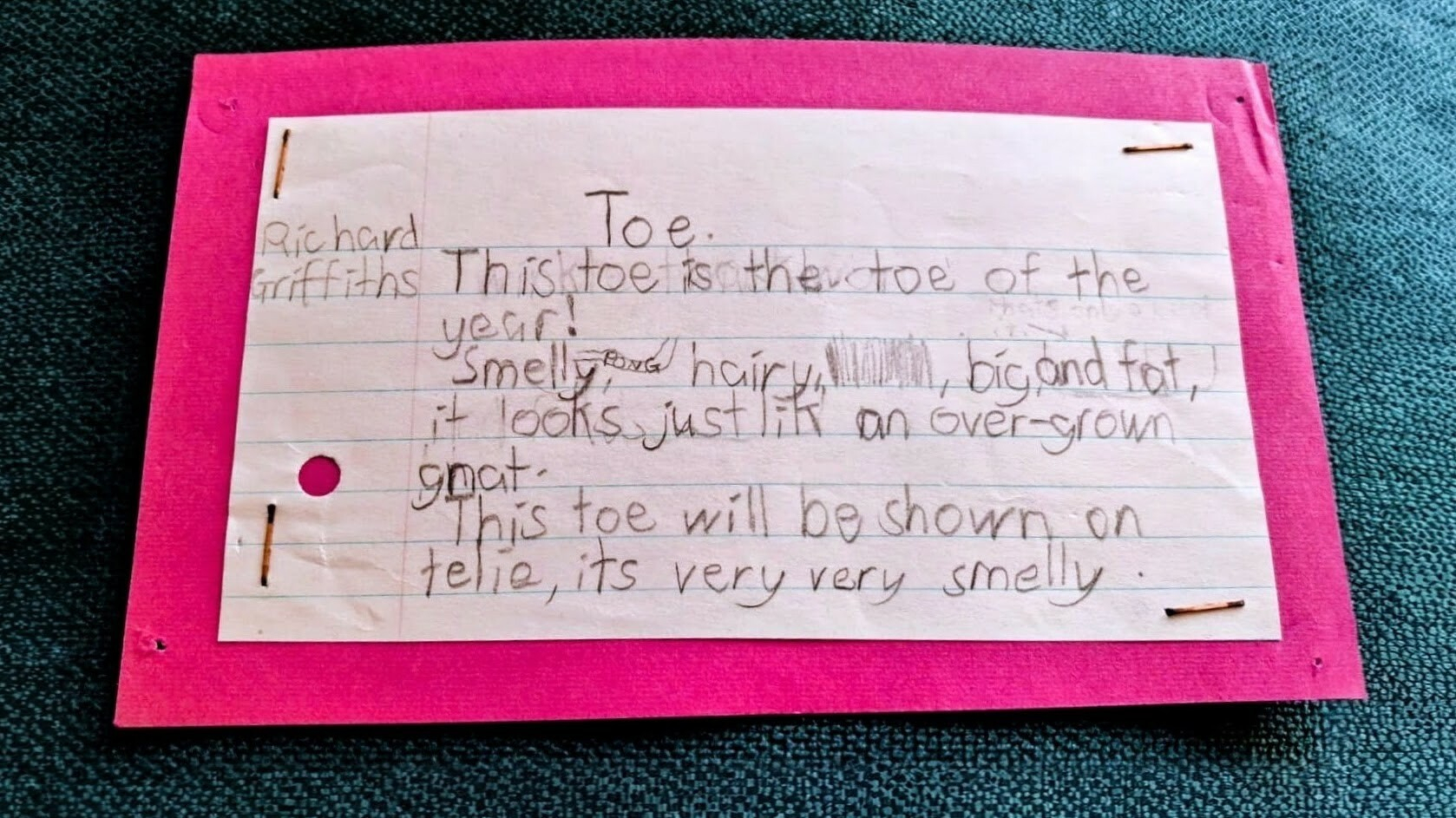

Last month, while my sister was moving house, she discovered a box of papers she’d never seen before. Inside was a collection of documents, decades old, that our parents must have gathered and kept from our childhood. There in a carefully wrapped pile was a sheaf of my sister’s old school reports. And next to them was a set of poems I must have written way back when I was a primary school student.

Perhaps you’ve had the experience of venturing into the attic or the basement and finding long-forgotten documents like these. But this chance rediscovery got me thinking about just how much has been lost to time.

Mostly we don’t bother archiving, and even when we do, there are later moments when we decide to spring-clean, rationalise, declutter, or tidy up.

These are all euphemisms for destroying the evidence.

Not that we shouldn’t do it, but I couldn’t help wondering at the sheer immensity of what must have been lost to history in this way. Admittedly, my childhood poetry and my sister’s school reports aren’t entirely essential for the public record, but what about the other items that well-meaning tidiers have chucked out? Some proportion of them, surely, must have been priceless.

Writing survives through luck and neglect

Given all the destruction of the centuries, and even just the spring-cleaning, it’s amazing that so much of the past still remains available to us, especially through the writing of contemporaries.

To take just one famous example: Leonardo da Vinci’s notes were almost lost because he left them to his favourite student, whose son inherited them and neglected them in a mouldering attic. Despite — or perhaps because of — the neglect, the notes survived and so today we can still marvel at Leonardo’s quickness of thought, virtuosity of line, and genius of innovation.

It’s a big win for forgetting to clear out the attic.

We’re not quite so lucky with John Donne, the poet of the English Renaissance, whose name, for some reason, is pronounced ‘Dunn’. His poems survive, but his commonplace book is currently lost — though its trail is tantalizingly clear.

According to Katherine Rundell’s lively biography Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne, Donne gave it to his eldest son, who left it to Izaak Walton’s son in his will. That made sense because Walton was Donne’s friend and biographer. But Walton’s son in turn left all his books and papers to Salisbury Cathedral. And that’s where the trail goes cold.

The commonplace book is completely missing.

Perhaps one day they’ll rediscover Donne’s commonplace book. If it’s ever found, Rundell says, it will cause ‘joyful chaos’ among the Donne community. On reading this I couldn’t decide which I loved more: the delightful concept of joyful chaos, or the endearing fact that there’s such a thing as the Donne community.

Donne’s genius depended on gathering scraps

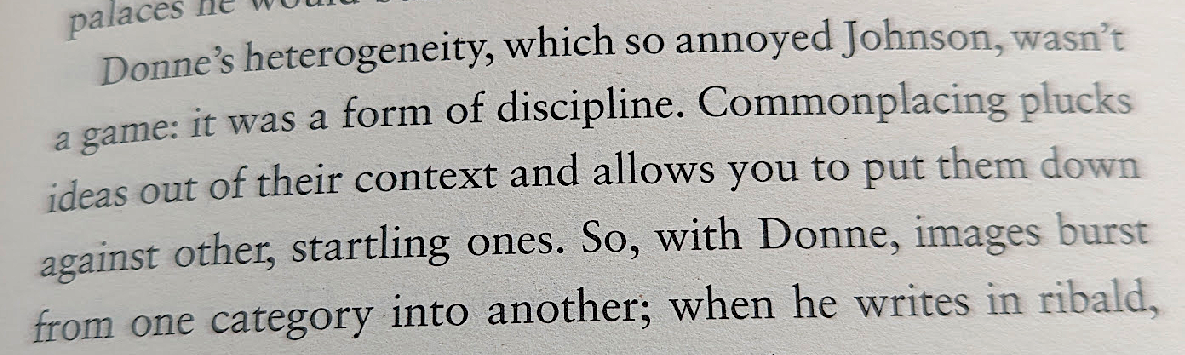

The loss, for fans of the poet, is particularly frustrating because Donne wouldn’t be Donne without his commonplace book. He lived in what we might call the golden age of commonplacing. It was an era that nurtured his collector’s sensibility and his obsession with hoarding the quotations of others. As Samuel Johnson said disapprovingly, in Donne’s work “the most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together.”

But this magpie tendency, as Rundell calls it, to gather and juxtapose, was hardly a flaw; it was central to his genius. Throughout his poetry, Rundell says, “one thought reaches out to another, across the barriers of tradition and ends up somewhere fresh and strange.”

Though Donne himself coined the term ‘commonplacer’ (another fact I learned from Rundell’s biography), the practice itself was codified by Erasmus, the doyen of Dutch humanism. He instructed readers to create headings at the top of each page, such as beauty, friendship, faith, hope, the vices and virtues. Then, while reading, you’d note down anything striking: a story, a fable, a pithy remark, a clever turn of phrase. The result was both a form of scholarship and a map of your own obsessions. Donne’s book, says Rundell, surely included: angels, women, faith, stars, jealousy, gold, desire, dread, death.

But of course, we don’t know. We haven’t seen it.

The purpose of the commonplace book wasn’t mere collection. As Erasmus explained, whenever a witty occasion demanded, you’d have “ready to hand a supply of material for spoken or written composition.” But despite this, the commonplace book wasn’t really designed for regurgitation. It offered raw material for a combinatorial, plastic process; a process that was half evidence-building and half treasure-hunting.

Like any intellectual pursuit, commonplacing created anxiety about doing it right. Even back then the market naturally monetised that worry, by selling ready-made commonplace books with the quotations already filled in. I find this amusing, but buying pre-compiled wisdom surely defeated the point. It’s the early equivalent of getting a chat bot to do your homework for you: easy but almost pointless.

The work itself is the point.

Sir Robert Southwell, President of the Royal Society, left some headings in his commonplace book forever blank (Academia and Tedium, tellingly), while others left him scribbling in increasingly tiny handwriting at the foot of the page, crossing out headings to make space. Each commonplace book is the unique record of the workings of a unique mind.

Donne built palaces from unrelated bricks

You can see the commonplace book’s influence throughout Donne’s poetry. In a single poem he might reference Aristotelian logic, Ptolemaic astronomy, Augustine’s discussion of beauty, and Pliny’s theory on poisonous snakes. In a poem about sexual inconstancy, he compares women to both foxes (apparently fairly normal for his day) and goats (apparently and understandably unusual).

The Twentieth Century poet T.S. Eliot understood what made this work. “When a poet’s mind is perfectly equipped for its work,” he wrote, “it is constantly amalgamating disparate experience.” For ordinary minds, experience remains chaotic, irregular, fragmentary. But for Donne, as Katherine Rundell observes,

“apparently unrelated scraps from the world were always forming wholes. Commonplacing was a way to assess material for those new connections: bricks made ready for the unruly palaces he would build.”

Donne himself was alert to the danger of mindless compilation. In his poem “Satire 2,” he mocked writers who merely copied others' words and regurgitated them as their own: like someone who eats your food and then claims the resulting waste as their supposedly better creation. Harsh, but memorable. And yes, the analogy certainly did make me think of ChatGPT and its copyright-denying siblings.

But he is worst, who (beggarly) doth chaw

Others' wits' fruits, and in his ravenous maw

Rankly digested, doth those things out spew,

As his own things; and they are his own, ‘tis true,

For if one eat my meat, though it be known

The meat was mine, th’ excrement is his own.

What lessons emerge from a book we’ve never seen?

First, you can’t simply jam together random quotations and expect to produce thoughtful prose. Johnson accused Donne of yoking heterogeneous ideas together by violence, yet Eliot saw that Donne’s “perfectly equipped poet’s mind” achieved something remarkable. The rest of us may need to work harder to overcome the illusion of integrated thought and produce the real thing.

Second, commonplacing risks collecting other people’s words without fully digesting them. Apparently there’s a German word for the kind of writing this can produce: Zitatsalat, ‘citation salad’. There are other methods — the Zettelkasten system, for instance, which I prefer — that encourage reflection and connection-making from the outset. I’ve taken a minimal approach to making notes, with just these affordances.

Third, it’s important to publish, not least because unpublished notes often end up lost. Leonardo da Vinci’s notes barely survived. Donne’s commonplace book is long gone (though I encourage you to check down the back of your sofa just in case). A scholar of the philosopher Charles Peirce recently told me that after Peirce left his voluminous papers to a university library, they reused them as scrap paper. Happily, someone realized the error before too much damage was done. And to cap it all, my own poem about the toe of the year nearly didn’t make it. And these days, when you’re gone someone will eventually press “delete.” Better to get your words out there while you can.

A short postscript:

Indeed, this very article was almost the victim of delayed publication. I wrote this, mostly, three months ago. Then my iPad’s note-writing app developed a mysterious glitch which made the app and all its notes unusable. Only the happy fact that I’d backed everything up ensured my words would be saved from the digital wreckage. Otherwise, oh the horror, as with Donne’s Commonplace book, you wouldn’t be reading this right now.

—

Further reading:

Rundell, Katherine. Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne. New York City: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022. ( see especially pages 36-39, the source of most of the quotes here )

Overcome the illusion of integrated thought

A minimal approach to writing notes

Get your words out there by publishing first

—

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now.

And if you found this article interesting you might like to sign up to the Writing Slowly weekly email digest. You’ll receive all the week’s posts in that handy email format you know and love.

Why your note-making tools don’t quite work the way you want them to - and what to do about it

Every so often I stumble upon a really clear articulation of a concept that makes sense of something I’ve been feeling but didn’t previously have a word for. I knew there was something there but I didn’t have the language to express it.

One of the most interesting articles I’ve come across recently is Artificial memory and orienting infinity by Kei Kreutler.

In this particular case the concept illuminated is the subtle, niggling tension between what I want to use my digital writing tools for and what they actually do. My writing tools, and possibly yours too, nearly do what I want, but not quite. What’s that about? Well, on reading this article, the tension became a whole lot clearer.

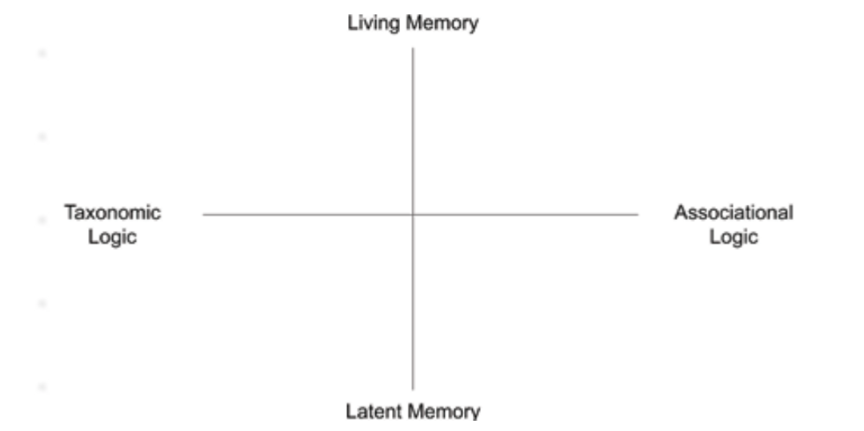

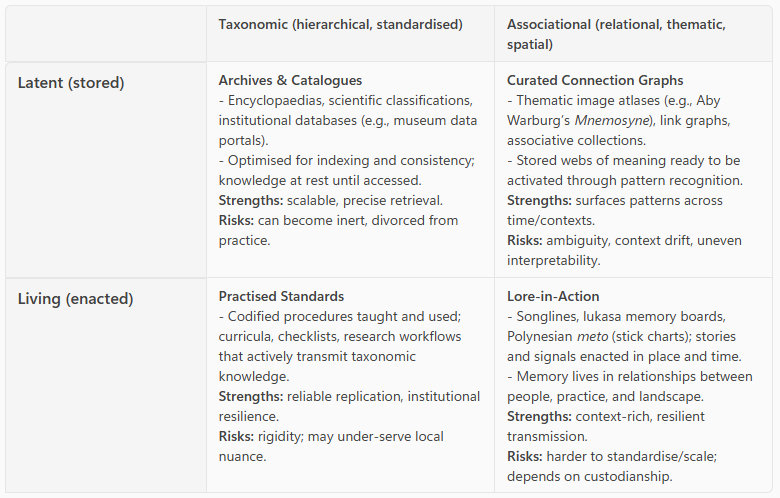

Kei’s article attempts to makes sense of memory in pair of dimensional scales: latent-living and taxonomic-associational.

-

Latent Memory

Refers to knowledge stored but not actively used.

Exists in archives, databases, or written records.

It is inactive until accessed or brought into practice. -

Living Memory

Knowledge that is actively transmitted and practised.

Maintained through oral traditions, rituals, and cultural engagement.

Keeps information dynamic and relevant in everyday life. -

Taxonomic Memory

Organises knowledge into structured, hierarchical categories.

Examples: Encyclopaedias, scientific classifications.

Emphasises order and standardisation for clarity and retrieval. -

Associational Memory

Links ideas through relationships, stories, or spatial metaphors.

Examples: Songlines, memory boards, or thematic connections.

Encourages flexible navigation and creative associations.

These four modes describe the different ways societies and individuals store, organise, and activate knowledge, ranging from static archives to dynamic cultural practices and from rigid hierarchies to fluid networks.

A summary of the framework described in Kei Kreutler’s article.

I’ve found this framework really illuminating. In particular the taxonomy highlights for me the point that our tools and methods lead to different outcomes. We shouldn’t expect latent, taxonomic memory devices (archives and catalogues) to perform the same functions and achieve the same outcomes as living, associational memory devices (lore-in-action).

It’s well worth reading the whole article. This four-fold framework clarifies the tension I often feel between my note-making intentions and my note-making tools. Whereas the standard tools tend towards latent, taxonomic memory, I’m far more interested in living, associational memory. And until now I didn’t quite have the right words to express this.

Well, this theory is all very well but how does it play out in the real world? Here’s a very practical example of what living, associational memory might look like in practice. The philosopher David O’Hara uses his bookshelves as a teaching device. As he discusses philosophy with his students he pulls the relevant books from his shelves, to create a pile of a dozen or more texts that he calls a ‘shelfie’.

Stored in the bookcase these books are latent memory, but this memory is activated by the discussion; it comes alive. Left on the shelves the books are ordered in some form of standard order (by subject or alphabetically, or whatever), but as they get pulled off the shelves to illustrate the discussion they become ordered by association. Then the hour is up and the little pile is re-shelved.

Every so often, my partner insists on reorganising our bookshelves in our living room. Apparently we have too many books, which is obviously not possible. Anyway this shuffling of the stacks drives me unreasonably crazy, makes me feel like I’ve undergone a lobotomy - and now, finally, I understand why: my extended mind has been messed up. My living, associational memory is undone, I’m being assailed by entropy.

So what’s the practical relevance of all this? Open up your note-making tool, whether that’s Obsidian, Notion, Apple Notes, a text editor, a collection of notecards, or a physical notebook, and ask yourself: is this designed for latent/taxonomic memory or living/associational memory?

I bet no one’s ever suggested that to you before, so how can you tell? You can look at how it wants you to organise things. Does it push you toward folders and tags, and hierarchies? Does it emphasise search and retrieval? That’s taxonomic thinking. Or does it encourage links, and serendipitous discovery, and bringing ideas into conversation with each other? That’s associational.

Then look at what it encourages you to do with your notes. Is it easy to transmit your precious knowledge (I’m guessing it’s precious), to share it, to get it out of your note-system to interact with the world? That’s heading in the direction of living memory. Or does it encourage you to store your knowledge away, to archive it rather than pass it round or create something with it. That’s oriented towards latent memory.

None of these dimensions are wrong in themselves, but knowing which type of memory your tool is optimised for helps explain that nagging tension I was feeling. You might be trying to use a filing cabinet like a conversation partner, or vice versa.

The question isn’t “which tool is best?” but “does this tool match what I’m actually trying to do?”

—–

Some further reading:

Notemaking helps you remember - and helps you forget

In this post I explore the dual nature of memory and forgetting through note-making and discuss how my notes become “conversation partners” with my future self - because I’ve forgotten what my past self thought. But I also consider that selective forgetting may have some advantages.

Don’t throw away your old notes

Though I didn’t know it at the time, this post is directly relevant to living vs. latent memory, because it’s about the Zettelkasten as a “conversation partner between my old self and my current self” and it considers how to create the right conditions for serendipity and associational connections.

My favourite tool is this notebook I made

This is about how I modified TiddlyWiki to suit me better. I wanted a rhizomatic tool for writing, and since I couldn’t find one I really liked, I adapted one for my own purposes. You might not need to invent your own tools, I said, but each of us gathers uniquely the unique contents of our own toolbox. And yes, when I grow up I want to be an aphorist.

How to write a better note without melting your brain

This is a practical guide to writing a note that might actually reach its potential. I also discuss Tim Ingold’s contrast between “textilic” (weaving) vs. “architectonic” (architecture) modes of creation, which I’m pretty sure is relevant to associational vs. taxonomic thinking.

What to do when you’ve made some notes: Write something

This post is all about the latent/living dimension, because here I’m suggesting that the point of making notes is to make something else with them, probably for others to read. Yes, it turns out I am quite opinionated about what I want to achieve with my tools. And if you click this link you’ll see a picture of me hard at work in my study overlooking the Sydney Opera House. That has to be worthwhile.

—–

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now.

And if you found this article interesting you might like to sign up to the Writing Slowly weekly email digest. You’ll receive all the week’s posts in that handy email format you know and love.

The Spiral of Mastery: Why the Greatest Experts Are Serial Beginners

The greatest experts aren’t afraid of starting again

Apparently, my tennis is rusty

Here in Australia the Christmas holidays take place in mid-summer, and my family spent a few days at a house with a tennis court. It was an amazing opportunity, for which we were hardly prepared. I hadn’t played in years. One family member had barely held a racquet before. But we all shared the same problem: our serves were terrible. The ball hit the net, or it veered wildly off court. The serve seemed like some monolithic, unreachable skill you either had or you didn’t.

The view from the court — that was amazing, but the tennis, to say the least, wasn’t flowing.

That was until someone suggested we break it down: grip, swing, ball toss, contact. We stopped trying to play and started drilling. Within a short while, the court was alive with movement and we were laughing instead of frowning with effort. Our natural talent hadn’t changed; it was just that our willingness to break the seemingly impossible into achievable parts made it somehow seem doable. And after a short while, it actually was doable. We were delivering serves that made it over the net, that you could also imagine returning.

This experience was a reminder that expertise is hardly ever about making a single massive effort to achieve something that seems impossible. You don’t get good at tennis all at once. Playing the game well is really a whole portfolio of tiny pieces of expertise you have to master one by one and piece together smoothly before you can reach actual proficiency. And even when you get there, that’s not the end. There’s always something, some element of your play, you can improve. Is mastery a destination to reach and then enjoy forever? No. It’s more like a spiral that requires us to return to the beginning again and again of a long series of micro-skills.

Experts Get Stuck Because They Stop Looking

But you can reach a point where it’s hard to see how to improve, or if it’s even worth it. For creative practitioners, there may come a moment when the work loses its spark. You’re competent, maybe even accomplished, but something vital has drained away and it feels like you’ve reached the plateau of your expertise. You can’t see what to improve because you’ve stopped looking. So you repeat what works because it works. Meanwhile, beneath the surface, your joy is slowly curdling into staleness.

There’s a cultural dimension to this trap. Experts aren’t supposed to feel like beginners. So we stay on this plateau, defending our position rather than climbing higher. The writer Ernest Hemingway understood this. Despite his Nobel Prize and decades of acclaim, he insisted: “We are all apprentices in a craft where no one ever becomes a master.” He wrote to a friend of his that “dopes would say you’ve mastered it”, but he continually felt like an apprentice.

How Do You Actually Get Better?

In their book Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise, Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool show that expertise is built through deliberate practice: the systematic isolation and refinement of specific sub-skills.

Take that tennis serve we all struggled with on holiday. Total proficiency is really just a messy stack of mastered micro-movements. You have the grip and the swing mechanics, but also the ball toss, the contact point, and the tactical intent. A player gains expertise not by playing endless matches but by drilling these elements until they’re second-nature. For writers, the equivalent sub-skills are less obvious but they still exist. It might come down to the rhythm of dialogue or the way a transition sentence functions, or to opening hooks, sensory detail, and the painful art of compression. Drilling these exercises might feel artificial because to an extent it is. But the artificiality is exactly what creates the conditions for focused improvement.

I found the map of learning: Shu Ha Ri

The traditional Japanese framework, Shu Ha Ri, maps this growth as a recurring cycle, a sort of beautiful, never-ending loop that keeps things interesting no matter how far advanced you become. In the Shu phase, you just dive into the work. It’s this foundational, deeply immersive period of copying a master’s handwriting or holding a racquet in that specific, stiff posture that eventually starts to feel like it’s natural (please don’t challenge me on this — as I say, I still can’t actually play tennis). Early on you’re essentially acting as a mirror, reflecting something great until it sticks.

Eventually, you move into Ha, the breakout phase. This is where the tinkering starts. It’s the time when you really start to play. You begin questioning the rules and adjusting your grip, or just messing around with sentence rhythm to see where the tradition ends and your own unique voice begins to shine through.

Then there’s Ri. In this Zen-like space, the rules have been digested so deeply they just… click. The skill happens through you rather than by you, which is a pretty incredible feeling when you finally hit that flow. I certainly haven’t reached this level with tennis, but I have had such moments while playing squash. It’s not so much that you’re playing the game as that the game is now playing you. But the best part is when the top of that mountain reveals a much bigger, sun-drenched one hiding right behind it. You’re invited back into Shu. The master becomes a student again, starting over with a fresh sense of humility and a genuine, open-eyed curiosity for what’s next. The danger is that as an accomplished expert it all gets so serious that you might forget you can go back to the start, you can still play, you can have fun.

You can pivot from expert back to beginner

If you look, you can sometimes see this same recursive loop even at the top of the pop charts. Here’s a well-known example: Taylor Swift during the pandemic. She’d spent a decade building her massive, glitter-cannon “pop industrial complex.” Then, suddenly, she retreats. She ends up in a flannel shirt, recording folklore in a bedroom, where she’s obsessing again over the fragile mechanics of acoustic storytelling like she’s still a teenager. She had to junk the “superstar” persona if she was going to rediscover the songwriter underneath.

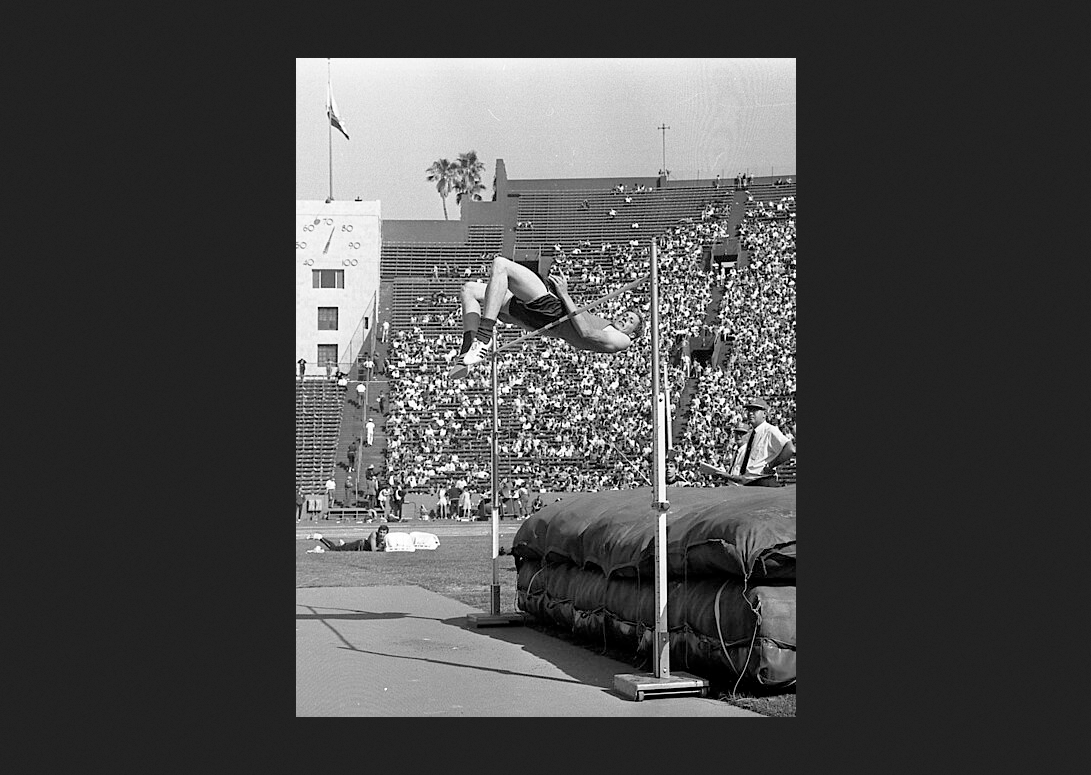

But it isn’t always about these polished pivots from glossy stars. There’s also Dick Fosbury at the 1968 Olympics. Before he showed up in Mexico City every “expert” high jumper on the planet was using the barrel-roll technique. This was basically a face-down belly-roll over the bar that everyone agreed was the limit of human potential. They’d already reached the end of what a scissor jump could achieve and now the barrel-roll was pretty much the rule.

Then Fosbury turns up and decides to jump over the bar head-first and backward instead.

It looked absurd. Here was this gangly young engineering student with mismatched running shoes, who looked like a camel on two legs, as the papers said at the time.

During his Shu phase of figuring it out, he was probably hitting the bar with his neck, landing on his head, and looking like a total amateur while everyone else was doing the proper barrel-roll technique. He had to be willing to look like a flop on the world stage just to prove that the experts' way of jumping was actually just a false ceiling that he could break through. If you watch the old footage, you can see way he has to psych himself up, then the hesitation in his run-up. There’s an electric, shaky moment where he has to choose to trust this new, unproven movement over the mastery he was supposed to have.

Backwards and head-first? It turned out not to be a flop at all. Instead he’d perfected the world-beating Fosbury Flop which almost everyone has used or adapted ever since. But this wasn’t magic. The reality is they’d only recently introduced deep foam mats for a safe landing. You can see this progression in a youtube video called Men’s high jump through the years! Fosbury saw this as an opportunity to become a beginner again, to try something new, and he took it, and it worked.

High jumper Dick Fosbury clearing the bar during 1968 Olympic trials at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Los Angeles Times, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Then, going back to pop, there’s the singer PJ Harvey. By 2007, she could play a rock guitar better than almost anyone alive. So, naturally, she decided to stop. She sat down at a piano, an instrument she barely understood, and forced herself to write the album White Chalk. If you listen to that record, you can hear the ghost of the beginner in it; there’s a kind of haunting, shaky tension, perhaps because her fingers don’t quite know where to go.

In an interview she said, “the great thing about learning a new instrument from scratch is that it […] liberates your imagination.” But I suspect she became a novice on purpose because she knew the “expert” version of herself was running out of things to say. And that’s not all. During the White Chalk tour she started performing on autoharp, another instrument she hadn’t perviously been known for.

You can see both instruments on this Youtube video from the time. PJ Harvey - KCRW 2007

PJ Harvey performing live at the Royal Festival Hall in London, United Kingdom on September 27, 2007. Ella Mullins, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Beginner’s Mind

Shunryu Suzuki, the Japanese monk who brought Zen to Northern California, noted that “in the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.” It’s an interesting way of looking at the world.

Execution requires certainty, the ‘few possibilities’ of the expert. But learning thrives on an open-ended sense of wonder, the ‘many possibilities’ of the beginner. Shoshin (Beginner’s Mind) is really just an intentional suspension of ego. It means looking at a weak sub-skill with total openness, gently setting aside that heavy, defensive armour of past achievement we all carry around. In the real world, this looks like a novelist with multiple published books happily sweating over a basic copywork drill. It’s an established painter returning to the simple magic of primary color-mixing, or a senior developer diving into a new language with the same enthusiasm they felt as a total novice. It’s Taylor Swift going back to basics; it’s Polly Harvey learning a new instrument live on stage; it’s Dick Fosbury attempting entirely the wrong kind of jump.

“When we have no thought of achievement, no thought of self, we are true beginners. Then we can learn something. The beginner’s mind is the mind of compassion. When our mind is compassionate, it is boundless… The most difficult thing is always to keep your beginner’s mind. … This is also the real secret of the arts: always be a beginner” - Shunryu Suzuki, Zen Mind, Beginners Mind: Prologue.

This openness is how you get the spark back. The plateau can sometimes dim the spark that made you pursue this path in the first place, but you can always find it again. To counter that staleness, you just move back into the learning zone. You embrace the risk of failing, a risk which is really just a part of the adventure, and you adopt that open, beginner’s gaze.

Where Do You Start?

Our tennis serves were still inconsistent after that Christmas holiday experiment. Our footwork was a joke. Actually I don’t think we even had anything you could properly call footwork. But still, the court felt alive. Breaking the skill down into its basic components was the thing that killed the frustration and let the joy back in.

If you’re not sure where to start with improving your writing, try this: Look at your last five finished pieces. What do they all avoid? What scenes do you consistently skip or rush through? That avoidance is a signal that this area can use some work. It might be action scenes or emotional confrontation. That’s your sub-skill.

Right now, pick one sub-skill you’ve been avoiding. Not your whole practice. One component. Dialogue attribution. The first sentence of a scene. If you’re an artist, maybe it’s colour mixing. Then set a timer for 15 minutes and drill only that. Don’t worry about the “big picture.”

Just wade, waist-deep into the spiral of continuous learning and let the flow take you.

Further Reading:

- Peak by Anders Ericsson (the science of deliberate practice).

- Big Magic by Elizabeth Gilbert (on creative courage). I wanted to dislike this but actually I loved it.

- Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Shunryu Suzuki (the original text on shoshin).

- A Life in Zen (an article about Shunryu Suzuki).

- Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters (my own exploration of this framework

2025 marked 250 years since the birth of author Jane Austen. In 2026 she still has something important to teach us: “Feel the importance of every day, and every hour as it passes”.

—-

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri. The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now in paperback and ebook.

Looking back at 2025: a year of writing slowly but thinking with curiosity. 🖋️

From the note-making of Roland Barthes and Leibniz to reflections on AI and Japanese learning methods, here is a full archive of last year’s posts: Link

#Writing #Zettelkasten #PKM #AI #Learning #Blog #2025 #Shuhari

The posts of 2025

I’m much better at writing new stuff than consolidating the old, but it’s time to review what’s been posted here during 2025. Short posts excluded, it’s quite a lot, considering I’m Writing Slowly.

There’s also a list of the posts of 2024 and the posts of 2023 too.

And don’t forget to check out my book, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters.

To get the latest posts straight to your in-box, subscribe to the weekly Writing Slowly email newsletter.

People

Roland Barthes on the purpose of writing notes

The Dance of Joyful Knowledge: Inside Georges Didi-Huberman’s Monumental Note Archive

Lord Acton took too many notes, but that doesn’t mean you have to

Leibniz created a haystack of notes that wouldn’t fit in his Zettelschrank

What Tim Berners-Lee Has to Teach About Effective Notes

Daniel Wisser’s notecards as art and archive

A search for meaning in the palace of lost memories: Thoughts on Piranesi, a novel by Susanna Clarke

What I Learned from Bob Doto about Making Effective Notes and Writing a Book

I’m unqualified to diagnose the following writers with ADHD but I’ll do it anyway

Mastering Any Skill, the Japanese Way. A review of Analysis of Shu Ha Ri in Karate-Do: When a Martial Art Becomes a Fine Art by Hermann Bayer, Ph.D.

Writing and Making notes

Maybe you can create coherent writing from a pile of notes after all

Semantic line breaks are a feature of Markdown, not a bug

Create a note system that indexes itself

Publishing Slowly. An article about my first book launch of the year.

My writing process oscillates between notes and drafts

Roland Barthes on the purpose of writing notes

The Dance of Joyful Knowledge: Inside Georges Didi-Huberman’s Monumental Note Archive

Lord Acton took too many notes, but that doesn’t mean you have to

Tame the chaos with just foour folders for all your notes

Five solutions to link rot in my personal note collection

Why not publish all your notes online?

From tiny drops of writing, great rivers will flow

I found a way to create order from my jumbled ideas

Leibniz created a haystack of notes that wouldn’t fit in his Zettelschrank

What Tim Berners-Lee Has to Teach About Effective Notes

Daniel Wisser’s notecards as art and archive

What I’ve learned from non-linear narratives

A search for meaning in the palace of lost memories: Thoughts on Piranesi, a novel by Susanna Clarke

What I Learned from Bob Doto about Making Effective Notes and Writing a Book

What to do when you’ve made some notes: Start writing

Don’t throw away your old notes

Don’t let your note-making system infect you with Archive Fever

I’m unqualified to diagnose the following writers with ADHD but I’ll do it anyway

I designed a book in three and a half hours

If there’s more than one way of seeing, there’s more than one way of organising

Watch in awe as a fleeting thought becomes a lasting note

Plenty of ways to write online

Open, free and poetic. The Web is 34 years old!

Is there a Zettelkasten method?

Use case for the Zettelkasten. Why use a Zettelkasten? Why indeed?

Back to the Information City? How knowledge visualisation shapes the journey

Keeping a diary is a way of living

Publishing means no more hiding. Publishing my book, I had the strange feeling of having crossed an invisible but very powerful threshold.

Why niche blogs and Small Rooms still win - even in the age of technofeudalism

Imitating the greats? Imitation can be a very effective form of learning, but it’s worth considering who to imitate, and how.

Trying to write slowly in 2025

The Unity of Pen and Sword: Understanding Bunbu Ichi

Learning

The future of the humanities is wide open

Influence is everything: novelty its flimsy dress. What happens when once fashionable ideas get left behind?

I designed a book in three and a half hours

Mastering Any Skill, the Japanese Way. A review of Analysis of Shu Ha Ri in Karate-Do: When a Martial Art Becomes a Fine Art by Hermann Bayer, Ph.D.

Back to the Information City? How knowledge visualisation shapes the journey

Imitating the greats? Imitation can be a very effective form of learning, but it’s worth considering who to imitate, and how.

What does it mean to transcend the rules?

Keeping a diary is a way of living

Japanese Shu Ha Ri: Is it Better Than Western Learning Methods?

There’s a fundamental flaw in how we learn about expertise

Shu Ha Ri and the philosophy of interior design

The Unity of Pen and Sword: Understanding Bunbu Ichi

AI

It’s a great time to be writing the future

To understand the future of AI, look to the past

Leibniz created a haystack of notes that wouldn’t fit in his Zettelschrank

Hot takes on our future with AI

Provocative words about learning, teaching, AI, and the timely value of history

There’s a fundamental flaw in how we learn about expertise

Other

The Sydney I know isn’t like what they’re showing on the news

Japanese paper films. Yes, in the 1930s the Japanese made a whole bunch of short movies using rolls of paper instead of celluloid.

— Check out my book, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters. And you can also subscribe to the weekly Writing Slowly email newsletter.

Fact checking the good news

I expect 2026 to be a better year than 2025, not through some kind of magic but because millions of people like you and me are working hard to make it so. Since I posted a link to a round-up of the under-reported good news from 2025 someone said ‘some of this was definitely written with ai, so might be worth fact checking 😂’.

I was a bit disappointed, since I wanted the good news to be true, and since I have to admit this could easily make me susceptible to getting taken in by unreliable slop. Well, life’s too short to check all the facts, even if someone is wrong on the Internet (obligatory xkcd link), and that famous cartoon of the guy trying to fix it is actually an accurate drawing of me1. But I thought I should at least do a quick audit. And what did this reveal?

-

Jaguars in Mexico up by 30%? Yes! According to Reuters.

-

China’s carbon emissions have been flat or falling for 18 months? Yes! According to Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, as reported in carbonbrief.org.

-

In May alone China installed 230 million solar panels, or nearly 100 per second? Yes! According to Foreign Policy.

-

Species extintion rates have declined over the last century? Yes! According to “Unpacking the extinction crisis: rates, patterns and causes of recent extinctions in plants and animals” by Kristen E. Saban and John J. Wiens, 15 October 2025, Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2025.1717.

-

Deaths from air pollution have dropped by 21% in a decade? Per 100,000 population, yes! According to IHME, Global Burden of Disease and reported by ourworldindata.org.

OK, that’s enough for now. These all check out and if you want to check more, try this: Pick one piece of good news that matters to you and spend 5 minutes or less verifying it with a primary source.

Look, you obviously don’t need me to tell you it’s not all good news. In South America the jaguars are still struggling etc. etc. But that’s not what the original article is claiming. The point is, people can and do act together to change things for the good and it actually works, even if the media mainly just reports endless disasters and crises.

This is not naive optimism, it’s a way of imagining a difficult future and working hard to make it reality. Resorting to inaction through despair would be a big media-induced mistake.

Oh, by the way, 26 years ago there was war in Kosovo. Now it’s the third safest country in the world (YouTube). As I said this kind of under-reported news isn’t magic; it’s people working together tirelessly to make change real.

“Come my friends,” said the poet Tennyson ages ago, “‘Tis not too late to seek a newer world”.

That’s how I’m beginning 2026 and I invite you to join me.

-

Want to find your own reliable good news? Start with established sources like Our World in Data, which visualizes peer-reviewed research, or follow science journalists at major outlets who link to primary sources. When you see a claim, check if it cites specific studies or data with DOI links. And try reading the original sources for yourself. Academic research can be hard to read but it gets easier with practice. I like The Conversation for readable research summaries.

-

Choose one issue that resonates with you—whether it’s public health, wildlife conservation, clean energy, air quality or something else — and find one organization working on it. Sign up for their newsletter, make a small donation, or volunteer an hour. Go in person to a local event. You don’t need to doom-scroll the bad news in 2026; instead you can add your small effort to the millions already making the good news happen.

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri. The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now in paperback and ebook.

-

On the Internet no one knows you’re a stick figure. ↩︎

The right kind of optimism in 2026

Happy New Year! May the next 12 months bring you peace and joy and blessing.

Here are a handful of hopeful articles to get your 2026 started on a positive note. I especially recommend the first one which I found deeply inspiring.

-

All the news the media missed in 2025 fixthenews.com (via Miraz Jordan.)

-

“The right kind of optimism is disciplined. It begins with the premise that action changes outcomes, then organizes institutions, incentives, and narratives to make that premise true.” mongabay.com.

-

The Sydney I know isn’t like what they’re showing on the news writingslowly.com.

“Bun without bu means authority withers, while bu without bun means the people remain in fear and distant.” —Fujiwara Shigenori, 1254.

Medieval Japan understood that true mastery requires balance. My latest article explores bunbu ichi and why “artists and fighters” belong together.

Read more: The unity of pen and sword: understanding bunbu ichi

#Bunbu #JapanesePhilosophy #Shuhari #SamuraiCulture #MedievalJapan #ArtAndWar #LifelongLearning #CulturalHistory #Mastery

The Unity of Pen and Sword: Understanding Bunbu Ichi

My recent book is subtitled “The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters”. But why artists and fighters, and why mention them together?

In medieval Japan, warriors weren’t really expected to choose between intellectual pursuits and martial prowess. Instead they were required to master both. This philosophy is captured in the concept of bunbu ichi (文武一), which literally means “the civil and the martial are one.”

The principle emerged from bunbu nidō (文武二道), the “two paths of writing and warring.” This phrase emphasized that true excellence required competence in both literary arts and combat. Like much in Japanese culture it originated in China, but the Japanese made it thoroughly their own. By the early Muromachi period (1336-1573), it had evolved into a foundational concept in Japanese political thought, as scholar Pier Carlo Tommasi notes in his 2018 research.

The warrior-ruler who embodied both scholarly learning and military skill became the cultural ideal. According to historian G. Cameron Hurst, by the mid-fourteenth century, bunbu ryōdō (文武両道) thinking was firmly established in Japan, with this dual-talented warrior as the model leader.

Scholars like Oleg Benesch and Thomas Conlan have explored how this paradigm shaped Japanese identity and warrior culture. Their research reveals that the civil-martial unity wasn’t static but evolved alongside Japan’s political landscape, particularly during the medieval period when warrior classes consolidated power.

This wasn’t particularly about producing well-rounded individuals though. The integration of literary and martial disciplines was part of a sophisticated understanding of governance and power. Warriors who could compose poetry, practice calligraphy, and engage with classical texts were seen as more legitimate rulers than those who relied solely on force.

“from the time of the sages of the past, they have followed the path of bun to the left and bu to the right, for bun without bu is such that authority withers, while bu without bun means that the people are in fear, and remain distant. Instead, bun and bu belong together so as to allow for virtue to spread.” - Fujiwara Shigenori, 1254 (quoted in Conlan, 2011:88).

Besides, as the Warring States period (1467-1603) ended and Japan unified under the Tokugawa shogunate (1603-1868), the role of the warrior classes transformed dramatically, from fighting large-scale military campaigns to serving primarily as administrators of the unified state. This shift made the bunbu ideal a practical necessity. To fulfill their new roles in peacetime society, warriors now needed literacy, administrative skills, and cultural refinement as much as they needed martial prowess.

I wrote my book Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters with this concept in mind. The juxtaposition of fighters and artists may sound strange to Western readers, but it’s fairly well understood in Japan, and it’s a duality echoed in Ruth Benedict’s classic anthropological study The Chrysanthemum and the Sword.

The legacy of bunbu ichi continues to influence Japanese culture today. It serves as a reminder that strength without wisdom is incomplete, just as scholarship without the courage to act remains unfulfilled. True mastery, according to this ancient wisdom, requires a delicate balance.

My book, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, is available now. Please check it out.

References

Benesch, Oleg. Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Benesch, Oleg. “National Consciousness and the Evolution of the Civil/Military Binary in East Asia.” Taiwan Journal of East Asian Studies 8, no. 1 (2011): 129–71.

Benedict, Ruth. The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1946.

Conlan, Thomas. “The Two Paths of Writing and Warring in Medieval Japan.” Taiwan Journal of East Asian Studies 8, no. 1 (2011): 85–127.

Hurst, G. Cameron. “The Warrior as Ideal for a New Age.” In The Origins of Japan’s Medieval World, edited by Jeffrey Mass, 209–233. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Tommasi, Pier Carlo. “The Bunbu Paradigm Reconsidered: Warrior Literacy and Symbolic Violence in Late Medieval Japan.” Proceedings of the Association for Japanese Literary Studies 19 (January 2020). doi.org/10.26812/…

I've written a book and here are the details!

Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters

Master the art of true learning in any field

The journey from novice to expert follows a timeless path, known in Japan as Shu Ha Ri. Inspired by the wisdom of Japan’s martial and artistic disciplines, this book will help you to:

- Understand how learning works in any skill or subject

- Find confidence and direction in your own learning journey

- Transform the way you think about gaining and sharing expertise

In an era dominated by digital learning and AI, we’ve lost sight of a fundamental truth: true learning is a deeply human and social act. Technology offers resources, but it can never replace the nuanced transmission of knowledge between a committed teacher and a keen student.

Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning highlights the dynamic partnership between student and teacher. It demonstrates that true expertise is a continuous cycle of learning, adapting, and passing on wisdom. To learn is to connect with past generations and bravely guide the next.

Whether you’re learning a craft, sport, or skill, or teaching one, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning will help you move beyond mere competence to achieve true excellence. If you’re ready for a more effective, human-centered path to mastering any skill, “Shu Ha Ri” is your essential guide.

守 破 離

Shu Ha Ri, the powerful concept from the traditional Japanese arts, provides an enduring framework for understanding the distinctly human journey of learning. Although it originated in Japan, it’s a set of ideas that go beyond cultural boundaries. This deceptively simple phrase, of just three short syllables, is key to passing on knowledge from one generation to the next, yet without stifling innovation and change.

Shu Ha Ri can be translated, quite simply, as ‘hold-break-leave’, a phrase which captures the evolving stages of learning:

守

Shu (Hold): At first the students meticulously imitate their teacher, grasping the fundamentals through close observation and practice. The teacher provides essential guidance in a protective environment, ensuring that students build a solid foundation right from the start of their learning journey.

破

Ha (Break): The students begin to experiment and develop their own style. Meanwhile, the teacher encourages exploration and independent thinking, helping students move beyond their frustrations to refine their skills and discover their unique flair.

離

Ri (Leave): The students transcend the teacher’s teachings, ultimately to emerge as experts themselves. The focus shifts from copying to creating. Students are now capable of not only applying their knowledge but also contributing to the field themselves, potentially even becoming teachers to future generations.

But proficiency isn’t the end of this journey. The path of learning is far from linear. It’s a cycle. True experts return again and again to their ‘beginner’s mind,’ the root of their quest for excellence.

その道に入らんと思う心こそ我身ながらの師匠なりけれ

(Sono michi ni iran to omou kokoro koso waga mi nagara no shishō narikere)To have the mind to enter this path

is, indeed, to have an inherent teacher.

— Rikyū, Hundred Verses, 1

To read Shu Ha Ri. The Japanese Way of Learning for Artists and Fighters, simply order the book (ebook or paperback) on Amazon, wherever you live.

Here are a few links to get you started:

- United States

- Australia

- UK

- Canada

- Japan (English language edition)

There’s a growing library of articles and practical discussion about Shu Ha Ri and how to implement it in both learning and teaching.

You can also subscribe to the weekly email digest.

💬 “I’m not posting memes and ‘hot takes’. No goats were surprised by amateur divers in the making of this article. I’m trying to provide thoughtful, eccentric observations for thoughtful (not at all eccentric) readers, so context is everything.”

The Sydney I know isn’t like what they’re showing on the news

Tragically my home city has been in the international news for all the wrong reasons and we’re all feeling traumatised and shocked and heartbroken.

What about you?

You only know what you see in the media, like the photo below. So beyond the Harbour and the Opera House, perhaps you don’t know what Sydney is actually like.

I thought I’d show you a snapshot of what it’s really like where I live, on Bidjigal land, the unceded territory of the Eora Nation.

The terrible attack at Bondi Beach has affected everyone personally and highlighted how we’re all interconnected. For example, one of the victims of the shooting played soccer for our local team. He was French and had lived in Sydney for three years. The team he played for was founded in the 1960s by Macedonian Australians.

A Jewish French Australian resident who played football for a Sydney team with a Macedonian heritage. This is a microcosm of the plural nature of this city. Everyone is something and something else too.

We belong to Australia and also have deep connections to the wider world.

In fact fewer than 20% of residents here in our local area have two parents who were born in Australia. And we’re stronger because of our tremendous diversity. Despite the actions of a tiny minority, Sydney is a fantastically successful multicultural city where we enjoy and celebrate the fact that our neighbours are truly diverse. In my suburb, just South of the centre, I live happily beside people who come from 179 different countries and speak many, many different languages. More than half of us speak a language other than English:

- Chinese (Mandarin and Cantonese)

- Greek

- Arabic

- Spanish

- Nepali

- Macedonian

- Indonesian

- Portuguese

- Bengali

- Italian

And that’s just the top ten.

Let me take you for a short walk around the neighbourhood. Our immediate neighbours come from China, Japan, Argentina, Lebanon and Australia. Across the road from our place, but behind the houses is our local primary school, which on Saturdays holds language classes for the local Macedonian community. A few doors down from our front gate, our nearest place of worship is a Chinese Christian church that holds services in Mandarin, Cantonese and English.

It’s just across from our nearest cafe, popular with the local Muslim community and also so insta-famous for its extravagant desserts that people come from all over the world just to try them. It’s next door but one to an Islamic education centre, for after-school religious instruction. And just down the end of the street is one of Sydney’s best baclava patisseries, run by Lebanese Christians. Turn right and you’ll reach a Shi’ite mosque that’s right next door to a Greek Orthodox church. To get there you pass the Greek Orthodox bookshop and two Nepalese restaurants. On the other side of the road is another Chinese-speaking Church which is across the railway tracks from the local Macedonian Orthodox church. This is just down a short lane from our local Catholic parish church which regularly holds masses in Italian, Urdu and Filipino as well as English. On a nearby corner is an Islamic masjid surrounded by several fine Bangladeshi, Filipino and Thai restaurants.

Meanwhile, on our main pedestrian shopping street I regularly get to choose whether to buy my groceries from an excellent Nepalese store or from a Lebanese or Chinese store, also excellent. I love having this choice. Then there’s a Vietnamese bakery, the kind that’s distinctively Australian. And a couple of places to buy fresh Macedonian burek - a more localised speciality, since you can’t get this everywhere in Sydney. There’s also a small Cantonese diner that I swear smells exactly like my memories of Hong Kong. And in this place with its tall shady plane trees, festivals are celebrated - Muslim, Christian and Hindu - and also completely secular, with jazz and other popular music. The lighting and seating has recently been improved and in the evenings people from many different cultures sit here side by side and in small groups, just to watch the world go by and enjoy the cool night air.

By the way, this is nothing special. Our suburb isn’t even particularly known for being multi-cultural. It’s just a typical part of Sydney.

Travel a little South or North and it’s more noticeably Chinese, further West and it’s more obviously Lebanese. But every community in Sydney has an incredible mixture of people from an improbably wide range of places.

That means it’s not all sweetness and light. We’re all different and we all hold different opinions. Our council held a fractious meeting about whether to impose sanctions against Israel due to its actions in Gaza. On both sides the debate was heated and painful emotions were expressed. Yet somehow tempers remained intact and the forthright exchange was civil and reasoned throughout. It was an amazing if uncomfortable demonstration of respect for democracy in action.

I’m trying to say that the attack at Bondi Beach doesn’t represent what Sydney is like in any sense. The Sydney I know is safe and welcoming to people of all faiths and origins.

According to Forbes the gun homicide rate in Australia is 62 times lower than in the United States.

We live in multicultural communities that are generally happy and relaxed. Our differences make us interesting and they make Sydney vibrant, as well as just beautiful. Inevitably there is friction when people from all around the world find themselves living on the same street and even in the same apartment block, and when their countries of origin or heritage are in conflict with one another. But we are forbearing with one another because we’re determined to make it work.

Yes, more than ever, it’s clear we have to work at this. The actions of a couple of extremists won’t stop us from caring about our neighbours and our neighbourhoods. The truth is the very opposite. People who try to divide us with hate won’t win.

I have no doubt that the events at Bondi will make us even more determined, because whichever way you look at it, and no matter who tries to deny it with lies and distortions, diversity is now and always will be the only reality.

—-

See also: The dream is diversity.

Meanwhile, please feel free to copy and distribute my manifesto:

12 days of Winter Wonder Photo Challenge by Micro.blog: Dec 15 - Frost 📷

We don’t have frost here so this is the best I could do. Also, it’s not Winter in Australia. Just saying.

💬"The term “breaking the mold” is common, but without having learned anything from others, one cannot depart from or break away from anything.” - Prof. Shigeru Ushida.

#shuhari #education #lifelonglearning

Shu Ha Ri and the philosophy of interior design

The late interior designer Professor Shigeru Uchida discusses the importance of Shu Ha Ri for design:

💬 “The current education system lacks “Shu.” There’s a total absence of the attitude to observe, study, and learn from others. The term “breaking the mold” is common, but without having learned anything from others, one cannot depart from or break away from anything.”

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri. The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now in paperback and ebook.

Trying to write slowly in 2025

Before I really got going with the Zettelkasten approach to making notes (and with micro.blog) I was publishing only a handful of posts here each year.

But then my productivity exploded.

In 2023 I published 202 posts here, and this post equals that count for 2025, even though the year isn’t done yet.

In 2025 I also edited a collection of essays and published my own book.

So I’m quite happy with the year’s output. And thank you for reading along with me, I really appreciate it.

But don’t worry, in 2026 I’ll still be trying to write slowly.

This little book would make a great present for the artist, fighter, learner, teacher, or straight-up Japan-lover in your life. Just saying.

Towards sunset, beneath Fushimi Inari Taisha, the city of Kyoto is laid out like a silver plate.

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now.

#Kyoto #FushimiInariTaisha #Japan #SunsetView #JapanTravel #JapanPhotography #VisitJapan #ShuHaRi #JapaneseCulture

Imitating the greats?

Imitation can be a very effective form of learning, but it’s worth considering who to imitate, and how.

Writers often seek to imitate the greats, but it interesting how far the star of some supposedly timeless writers can fade. Here’s William Zinsser, the well-read author of ‘Writing to learn’, on how he did it.

“Writing is learned by imitation. I learned to write mainly by reading writers who were doing the kind of writing I wanted to do and by trying to figure out how they did it. S. J. Perelman told me that when he was starting out he could have been arrested for imitating Ring Lardner. Woody Allen could have been arrested for imitating S. J. Perelman. And who hasn’t tried to imitate Woody Allen? Students often feel guilty about modeling their writing on someone else’s writing. They think it’s unethical—which is commendable. Or they’re afraid they’ll lose their own identity. The point, however, is that we eventually move beyond our models; we take what we need and then we shed those skins and become who we are supposed to become.”

So who are these people I’ve never heard of, I wondered, who could all have been arrested for imitating one another? I mean, they couldn’t, could they? It’s not actually illegal, is it? Or did Zinsser mean plagiarism?

It turns out that Ring Lardner was an American sports journalist and satirist whose work was greatly admired by many of the major authors who were his contemporaries. In his high school newspaper Ernest Hemingway used the pen name, ‘Ring Lardner Jr’. Lardner became a friend of F. Scott Fitzgerald and he inspired the writing of John O’Hara (another great writer whose name is seldom heard these days). In The Catcher in the Rye, J.D. Salinger gave Lardner a backhanded compliment by having his protagonist, Holden Caulfield, name Lardner as his second favourite author. So for Hemingway at least the juvenile imitation seems to have extended to impersonation.

Clearly I need to read some Ring Lardner.

S.J.Perelman was a humourist, writing especially for the New Yorker. He was admired by T.S. Eliot, Somerset Maugham, Garrison Keillor, Frank Muir, and Woody Allen. Another writer I’ve never heard of, who seems to have been inspirational. But then…

“Who hasn’t tried to imitate Woody Allen?” Is a question I’ll leave hanging in the wind.

Author and academic Adam Roberts has an interesting post about Jonathan Buckley’s novel, One Boat (2025), which appears to use Laurence Durrell’s adjectives as a model for how one of his own characters might over-write their diary. Durrell is an author whose star has certainly faded, even though he was nominated several times for the Nobel Prize for Literature. And his style is certainly not admired these days. As Roberts says,

“giving his narrator these Durrellisms: the point of this adjectival affectation, or addiction, is to characterize her as someone groping, somewhat desperately, for expression, or the impossibility thereof”

Well, whether this is a deliberate imitation in order to show a diarist whose purple prose, like Durrell’s gallops away from them, or whether, as Adam’s seems to suspect, it isn’t, whether Buckley was doing something very clever and ‘meta’ with his character’s imitation, or whether he was just getting away with it, all the same, the novel was long listed for the Booker Prize.

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri. The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now.