Aby Warburg's Zettelkasten and the search for interconnection

Aby Warburg and the compulsion to interconnect

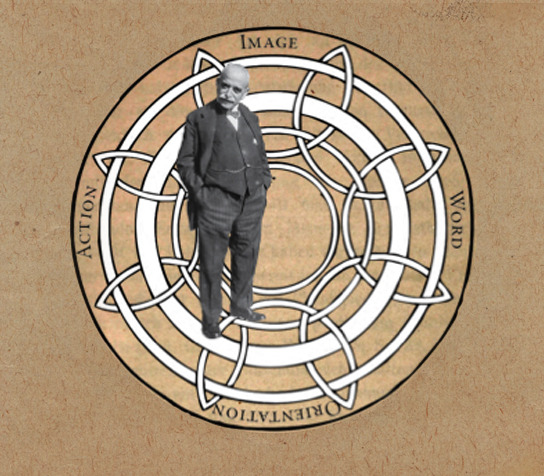

Aby Warburg was a German art historian obsessed with the connections he saw across European and Mediterranean culture in the afterlife of Antiquity. He even coined a phrase: Verknüpfungszwang - the compulsion to find connections.

“Coining a word that is as fitting as it is symptomatic of the urge it describes, [Aby] Warburg spoke of his Verknüpfungszwang. This ‘compulsion to interconnect’ lies not only at the root of his research and working methods. It is also manifested in regular references within his work to events in his private life, his family and collaborators.” - The Warburg Institute

Three projects in particular display Warburg’s extraordinary scholarly methods.

“The library, panels and boxes formed the ensemble of supports on which Aby Warburg’s spiritual work and intellectual creativity were based.” - Benjamin Steiner, Aby Warburgs Zettelkasten Nr. 2 “Geschichtsauffassung”, In: Heike Gfrereis / Ellen Strittmatter (Hrsg.): Zettelkästen. Maschinen der Phantasie (Marbacher Kataloge, 66). Marbach 2013, S. 154-161.

Taken together, these three amount to a technology for exploring Warburg’s obsession with interconnection.

Image source: Helix Center Warburg Symposium

The Zettelkasten as a thread through the labyrinth of thought

The first technology of note is Warburg’s Zettelkasten, his collection of index boxes, containing notes on many subjects.

“Aby Warburg’s collection of index cards (III.2.1.ZK), containing notes, bibliographical references, printed material and letters, was compiled throughout the scholar’s life. Ninety-six boxes survive, each containing between 200 and 800 individually numbered index cards. Cardboard dividers and envelopes group these index cards into thematic sections. The online catalogue reproduces the structure of the dividers and sub-dividers with their original titles in German and consists of about 3,200 items.” - Warburg Institute Archive

“…Warburg apparently worked constantly with these boxes, and, as his first biographer Carl Georg Heise has reported, he often stood with a strained facial expression bent over the mass of papers and arranged and shifted the individual cards in a long-lasting and never-ending process of order. “Those who follow Warburg’s note box follow his train of thought; from the banking system in Florence, the medieval trading company, the development of individuality, the restless professional work of the Calvinists and the Reformed form of asceticism, to Warburg’s own origin from the old Jewish banking family. The slip box is Warburg’s Ariadne’s thread through his labyrinthine library like his labyrinthine thinking: from the werewolf to the historical concept. A thought, an idea or a new concept does not emerge in a linear progression, but in a process of reciprocating units of ideas and cross-references, which continues until new intersections and nodes have formed.” - Benjamin Steiner, Aby Warburgs Zettelkasten Nr. 2 “Geschichtsauffassung”, In: Heike Gfrereis / Ellen Strittmatter (Hrsg.): Zettelkästen. Maschinen der Phantasie (Marbacher Kataloge, 66). Marbach 2013, S. 154-161.

According to Fritz Saxl, Warburg’s assistant and collaborator, “this vast card-index had a special quality… they had become part of his system and scholarly existence”.

“Often one saw Warburg standing tired and distressed bent over his boxes with a packet of index cards, trying to find for each one the best place within the system; it looked like a waste of energy. […] It took some time to realise that his aim was not bibliographical. This was his method of defining the limits and contents of his scholarly world and the experience gained here became decisive in selecting books for the Library.” - Fritz Saxl, The History of Warburg’s Library (1943-44, p. 329), quoted in Mnemonics, Mneme And Mnemosyne. Aby Warburg’s Theory Of Memory, Claudia Wedepohl (p.389).

A library of good neighbours

Second of note, and much larger than the card-index, is Warburg’s library. As the oldest son, Aby Warburg was in line to inherit his family’s seriously wealthy banking business. But his lack of interest in finance led him to offer the business to his younger brother Max, on the condition he could purchase any books he needed for his research into his true interest, art history. It may have seemed like a modest request, but Warburg’s book collection grew ever larger and eventually expanded into a significant research library. This library was organised like no other. The shelves, and eventually whole rooms were arranged to enable serendipitous connections across and between categories.

“the book you need might not necessarily be the one you were looking for. It might, in fact, be the one next to it. The books are shelved around the law of the good neighbour, meaning that the library’s collection is organised thematically instead of by author, title, or publication date. Gertrud Bing, an architect of the classification system and director of the Institute when it moved to London, said that ‘the manner of shelving the books is meant to impact certain suggestions to the reader who, looking on the shelves for one book, is attracted by the kindred ones next to it, glances at the sections above and below, and finds himself involved in a new trend of thought which may lend additional interest to the one he was pursuing’. Although the Warburg’s serendipitous system may initially seem unconventional and somewhat esoteric, the structuring of the library’s collection around the law of the good neighbour means that it is much easier for readers to discover and find texts they didn’t even know they needed within the interconnected, interdisciplinary classmarks. For Warburg, every book was useful in the context of the whole collection.”

…“the arrangement of the books at the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, the first Warburg library in Hamburg, was intended to encourage rather than obstruct discoveries. Whenever Warburg, an avid book collector, took receipt of one of his many deliveries of new acquisitions, he would rearrange the shelves to accommodate each new book into the collection. In this way, his theories on the interrelation of various images, literary motifs and disciplines found physical form in the arrangement of the books on the shelves. Bing remarked that ‘Warburg had chosen and arranged the books like stones from a mosaic of which he had the pattern in his mind’. They were collected for research into specific areas, under a general theme of the afterlife of antiquity.” Source: The Warburg Institute

An Atlas of Images

The third technology for making connections was Warburg’s visual Memosyne Atlas, intended to demonstrate in a series of large panels the lines of connection between artistic motifs in varying periods and locations.

“Warburg believed that these symbolic images, when juxtaposed and then placed in sequence, could foster immediate, synoptic insights into the afterlife of pathos-charged images depicting what he dubbed “bewegtes Leben” (life in motion or animated life).” - ZKM Center for Art and Media

Warburg’s institutional legacy

These three enterprises, card index, library and atlas, are today combined into the Warburg Institute, which began life in Hamburg and since 1944 has been in London.

Above the front door of the Institute is inscribed the Greek word MEMOSYNE. Warburg saw this not straightforwardly as the name of the goddess of memory, but as a sphynx presenting a great riddle. The Institute revolves around memory as a problem. What is memory? How does it persist in culture and individuals, and especially through art?

“In the first public occurrence of the word “Mnemosyne” I am aware of in his writings, found in the annual report on the Library for the year 1925, Warburg identifies Mnemosyne not as the goddess of Memory and mother of the Muses but rather as “the great Sphynx,” out of whom he hopes “to unlock, if not her secret, at least the formulation of her riddle [der grossen Sphynx Mnemosyne, wenn auch nicht ihr Geheimnis, so doch die Formulierung ihrer Rätselfrage zu entlocken]”” – Davide Stimilli, «Aby Warburg’s Impresa», Images Re-vues (En ligne), Hors-série 4, 2013.

Arguably, Warburg’s self-diagnosed Verknüpfungszwang, his ‘compulsion to interconnect’ hindered the completion and publication of his work. Perhaps his constant sorting and re-sorting represented a kind of perfectionism, or even a form of obsessive-compulsive behaviour. Indeed, he spent several years battling significant mental health problems and the end published comparatively little.

However, in another sense, through his Zettelkasten, his library and his atlas of images, the compulsion to interconnect became Warburg’s life’s work. It is telling that though Warburg left relatively few completed texts, his institutional legacy, especially through London’s Warburg Institute and Hamburg’s Warburg-Haus, has proved extremely influential and highly intellectually fertile over many decades - and continues strongly into the Twenty-first Century.

In his novel The White Castle (1998), Orhan Pamuk’s narrator says: “I suppose that to see everything as connected with everything else is the addiction of our time.” The life and legacy of Aby Warburg, shows that this doesn’t have to be a pointless pursuit of arbitrary links but can generate lasting knowledge and meaning with wide implications.

Further reading and viewing:

Chernow, Ron (1993). The Warburgs: The Twentieth Century Odyssey of a Remarkable Jewish Family. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0525431831.

The Warburg Institute Library: A Brief Description

Introduction to the Warburg Institute Library and Collections - description of Warburg’s Zettelkasten at 8:36

Aby Warburg: Metamorphosis and Memory - and Chris Aldridge’s online notes on this documentary (which is how I discovered it).