Atomic Notes

-

All the news the media missed in 2025 fixthenews.com (via Miraz Jordan.)

-

“The right kind of optimism is disciplined. It begins with the premise that action changes outcomes, then organizes institutions, incentives, and narratives to make that premise true.” mongabay.com.

-

The Sydney I know isn’t like what they’re showing on the news writingslowly.com.

-

It’s naive to trust Reddit’s figures, but that’s what they say, and you can’t do your own analytics. Well, I can’t anyway. ↩︎

-

I’m borrowing a taxonomy of social media that includes big rooms, small rooms and many rooms. ↩︎

-

He’s the creator of the Tinderbox notemaking app. ↩︎

Every interface is an argument about how you should feel. - Phantom Obligation | Terry Godier

This is my view of writing and note-making apps, but we can change them, to feel how we want, not how someone else wants us to.

The Toe of the Year and the Curious Case of John Donne's Missing Commonplace Book

Last month, while my sister was moving house, she discovered a box of papers she’d never seen before. Inside was a collection of documents, decades old, that our parents must have gathered and kept from our childhood. There in a carefully wrapped pile was a sheaf of my sister’s old school reports. And next to them was a set of poems I must have written way back when I was a primary school student.

Perhaps you’ve had the experience of venturing into the attic or the basement and finding long-forgotten documents like these. But this chance rediscovery got me thinking about just how much has been lost to time.

Mostly we don’t bother archiving, and even when we do, there are later moments when we decide to spring-clean, rationalise, declutter, or tidy up.

These are all euphemisms for destroying the evidence.

Why your note-making tools don’t quite work the way you want them to - and what to do about it

Every so often I stumble upon a really clear articulation of a concept that makes sense of something I’ve been feeling but didn’t previously have a word for. I knew there was something there but I didn’t have the language to express it.

One of the most interesting articles I’ve come across recently is Artificial memory and orienting infinity by Kei Kreutler.

In this particular case the concept illuminated is the subtle, niggling tension between what I want to use my digital writing tools for and what they actually do. My writing tools, and possibly yours too, nearly do what I want, but not quite. What’s that about? Well, on reading this article, the tension became a whole lot clearer.

Looking back at 2025: a year of writing slowly but thinking with curiosity. 🖋️

From the note-making of Roland Barthes and Leibniz to reflections on AI and Japanese learning methods, here is a full archive of last year’s posts: Link

#Writing #Zettelkasten #PKM #AI #Learning #Blog #2025 #Shuhari

The posts of 2025

I’m much better at writing new stuff than consolidating the old, but it’s time to review what’s been posted here during 2025. Short posts excluded, it’s quite a lot, considering I’m Writing Slowly.

There’s also a list of the posts of 2024 and the posts of 2023 too.

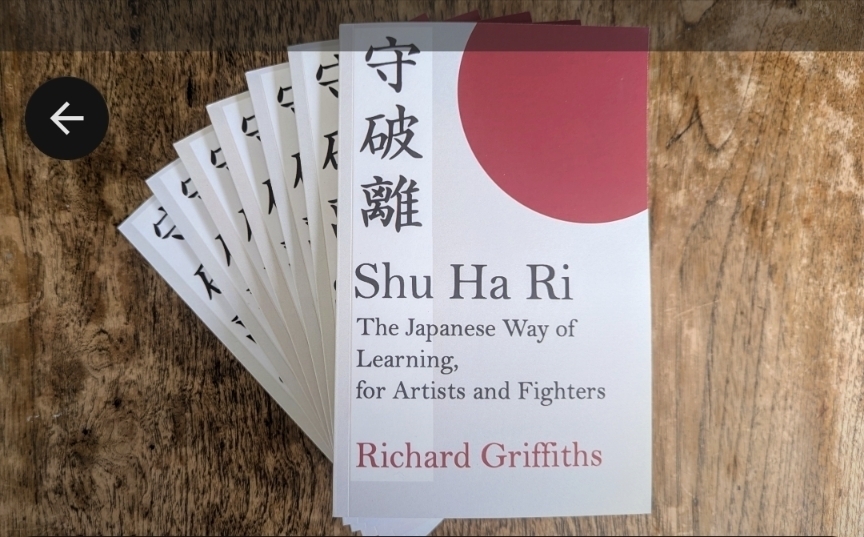

And don’t forget to check out my book, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters.

To get the latest posts straight to your in-box, subscribe to the weekly Writing Slowly email newsletter.

The right kind of optimism in 2026

Happy New Year! May the next 12 months bring you peace and joy and blessing.

Here are a handful of hopeful articles to get your 2026 started on a positive note. I especially recommend the first one which I found deeply inspiring.

Trying to write slowly in 2025

Before I really got going with the Zettelkasten approach to making notes (and with micro.blog) I was publishing only a handful of posts here each year.

But then my productivity exploded.

In 2023 I published 202 posts here, and this post equals that count for 2025, even though the year isn’t done yet.

In 2025 I also edited a collection of essays and published my own book.

So I’m quite happy with the year’s output. And thank you for reading along with me, I really appreciate it.

But don’t worry, in 2026 I’ll still be trying to write slowly.

This little book would make a great present for the artist, fighter, learner, teacher, or straight-up Japan-lover in your life. Just saying.

Imitating the greats?

Imitation can be a very effective form of learning, but it’s worth considering who to imitate, and how.

Writers often seek to imitate the greats, but it interesting how far the star of some supposedly timeless writers can fade. Here’s William Zinsser, the well-read author of ‘Writing to learn’, on how he did it.

“Writing is learned by imitation. I learned to write mainly by reading writers who were doing the kind of writing I wanted to do and by trying to figure out how they did it. S. J. Perelman told me that when he was starting out he could have been arrested for imitating Ring Lardner. Woody Allen could have been arrested for imitating S. J. Perelman. And who hasn’t tried to imitate Woody Allen? Students often feel guilty about modeling their writing on someone else’s writing. They think it’s unethical—which is commendable. Or they’re afraid they’ll lose their own identity. The point, however, is that we eventually move beyond our models; we take what we need and then we shed those skins and become who we are supposed to become.”

So who are these people I’ve never heard of, I wondered, who could all have been arrested for imitating one another? I mean, they couldn’t, could they? It’s not actually illegal, is it? Or did Zinsser mean plagiarism?

It turns out that Ring Lardner was an American sports journalist and satirist whose work was greatly admired by many of the major authors who were his contemporaries. In his high school newspaper Ernest Hemingway used the pen name, ‘Ring Lardner Jr’. Lardner became a friend of F. Scott Fitzgerald and he inspired the writing of John O’Hara (another great writer whose name is seldom heard these days). In The Catcher in the Rye, J.D. Salinger gave Lardner a backhanded compliment by having his protagonist, Holden Caulfield, name Lardner as his second favourite author. So for Hemingway at least the juvenile imitation seems to have extended to impersonation.

Clearly I need to read some Ring Lardner.

S.J.Perelman was a humourist, writing especially for the New Yorker. He was admired by T.S. Eliot, Somerset Maugham, Garrison Keillor, Frank Muir, and Woody Allen. Another writer I’ve never heard of, who seems to have been inspirational. But then…

“Who hasn’t tried to imitate Woody Allen?” Is a question I’ll leave hanging in the wind.

Author and academic Adam Roberts has an interesting post about Jonathan Buckley’s novel, One Boat (2025), which appears to use Laurence Durrell’s adjectives as a model for how one of his own characters might over-write their diary. Durrell is an author whose star has certainly faded, even though he was nominated several times for the Nobel Prize for Literature. And his style is certainly not admired these days. As Roberts says,

“giving his narrator these Durrellisms: the point of this adjectival affectation, or addiction, is to characterize her as someone groping, somewhat desperately, for expression, or the impossibility thereof”

Well, whether this is a deliberate imitation in order to show a diarist whose purple prose, like Durrell’s gallops away from them, or whether, as Adam’s seems to suspect, it isn’t, whether Buckley was doing something very clever and ‘meta’ with his character’s imitation, or whether he was just getting away with it, all the same, the novel was long listed for the Booker Prize.

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri. The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now.

Why niche blogs and Small Rooms still win - even in the age of technofeudalism

Views? I’ve had a few

Blogging is about creative expression, but as Tom Critchlow observes, it’s also about finding the others. I love blogging, and I have a personal blog that I love writing on. I guess you already know that, right? But I have to admit it, the Internet doesn’t treat blogs particularly well. The issue is that there’s no discovery flywheel for a blog. Google search is unlikely to make you visible, so you have to do all the work yourself of promoting it to potential readers. And as everyone knows, attention is a scarce resource these days. In contrast, social media thrives on showing people what you’ve made and algorithmically fine-tuning this to reach as many of the right people as possible.

I don’t love social media. In fact I do my best to avoid it. But I don’t mind forum sites so much, where the moderation keeps things at least a little civil.

Well, happily, my blog does have readers, a few at least.

To monitor reading figures, I use a very basic analytics service which respects users' privacy.

I could see from the dashboard that by June 2024 my site was getting about 1,200 views in a month. That’s amazing - thank you, to all of you, especially the keen ones right at the front taking notes! You’ll do well in the test later.

.

.

This is what a thousand people look like, though they’re not always as keen as this lot.

By July 2025 the count had risen to 6,000 views a month, where it now hovers. This may seem like a small number compared with how many times Beyonce’s been listened to, but it also compares very well with the number of people I can shout to across a crowded bar.

Now the most viewed individual post in June 2024 gained 216 views. It’s a more select crowd, but a crowd all the same! (Thanks for cheering, by the way).

A crowd of 250 people is still a crowd.

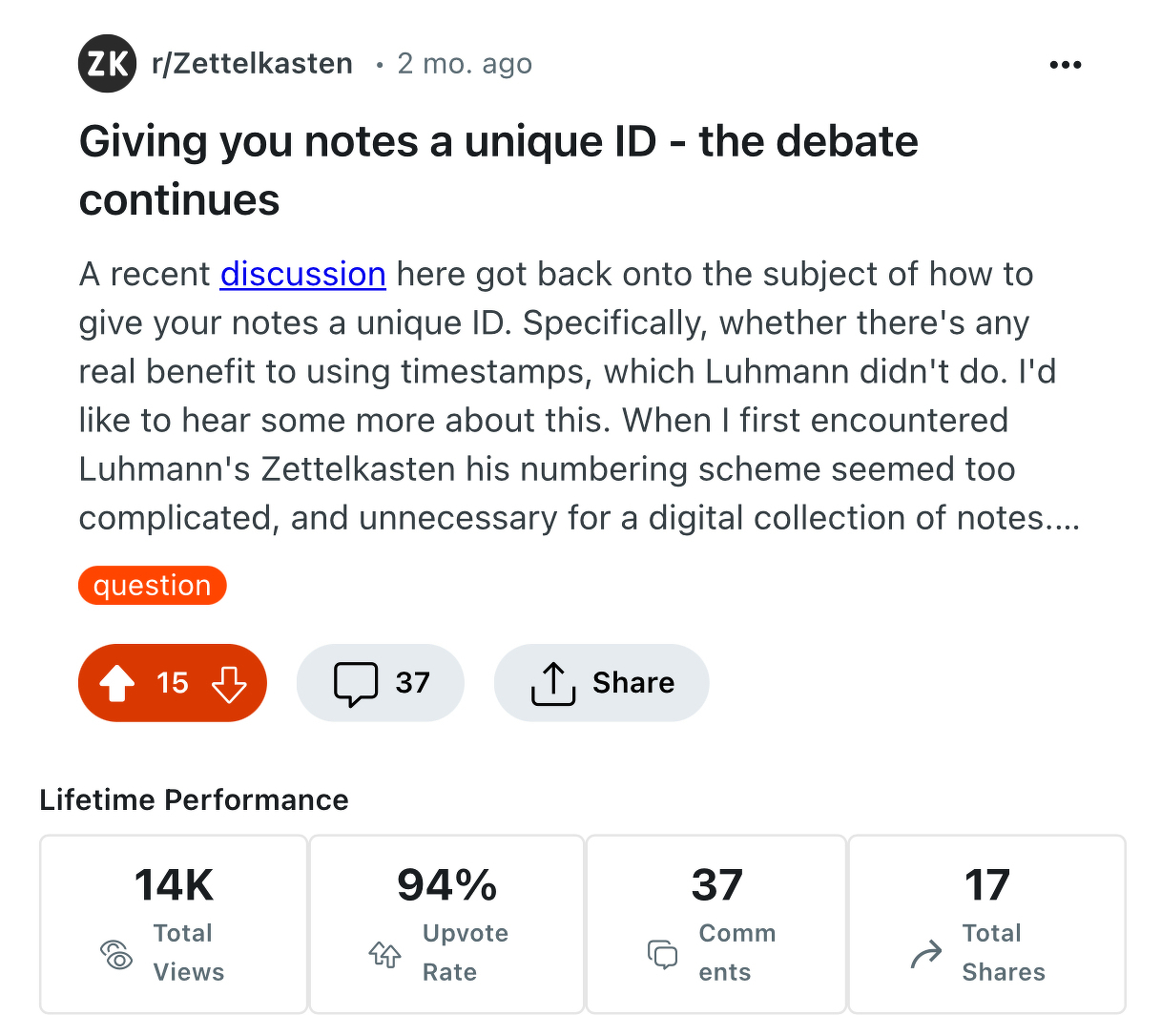

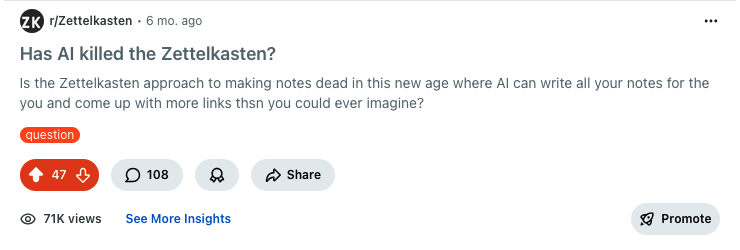

And a year later it was still gaining 64 views per month. Here’s the thing though. The same post with 216 views on my website reached considerably more readers on Reddit. It had 3,200 views there, which is about fifteen times more eyeballs! And a year later it had doubled that count.

And one of my more popular posts on Reddit has had 14,000 views, which, amazingly, is more views than this tennis match had!1

This tennis match had 10,000 viewers - almost as many as my crappy post on Reddit

But that’s not the very most popular post of mine on Reddit. That would be this more recent one, with 71,000 views, a lot like this exciting football match:

These audience size images, by the way, come from Visualizing crowd sizes.

It’s ironic that my most viewed piece of writing is a single sentence long and it contains a very obvious spelling mistake.

Now to me this looks like a very big stadium. Top sports teams and pop stars would be happy with those numbers. But if you’ve posted stuff on the big platforms like Facebook, Instagram and Xitter (I’m told the X is pronounced ‘Sh’), you’re probably already laughing at these ‘tiny’ numbers. By jumping off your roof into a paddling pool with a goat in it you’ve probably enjoyed millions of views. You’ve probably gone totally viral. You’re probably a certified influencer too. But the thing is…

I don’t want to be a serf on someone else’s plantation

I can’t stand technofeudalism, in which a few billionaires own the platforms and we’re just sharecroppers in their extractive systems. Unhappily, as economist Yanis Varoufakis observes in his book, Technofeudalism, it’s the state of the world these days.

I’m never going to jump off my roof into this paddling pool, not even for views. Not even for likes.

I want a different world (I know, right?), in which data portability and interoperability are the norm, so that if I want to switch platforms I can take my ‘connections’ with me. As Professor Sinan Aral, author of Hype Machine, has imagined, “consumers would own their identities and could freely switch from one network to another.” This wouldn’t just be good for me, it would be good for the whole ecosystem, since it would give the neo-feudal platform overlords an incentive to provide a better service than that of their competitors. The Three-legged Stool is just one vision of how this could work in practice.

Meanwhile, I support services that already support interoperability. My blog is hosted by Micro.blog, which encourages me to syndicate it to other places, including Mastodon and BlueSky, which also support (some) interoperability. I’m anticipating the arrival of the Pluriverse by building it, one blog post at a time.

On the other hand, there’s a certain logic to performing where the audience is. When I was a kid I used to practice my music in public by busking. And I always busked where the crowds were, not down an empty back alley where no one was listening. My parents disapproved, until I told them how much I was earning.

If you believe your work is worth reading, then you probably also believe it’s worth getting it read by more than one person.

It’s a bit of a contradiction. Even progressive organisations like New Public, which exist ‘to reimagine social media’ nevertheless use extractive venture-capital platforms like Substack, which allegedly profits from hosting Nazis. This seems a far cry from New Public’s mission of ‘building digital public spaces that connect people, embrace pluralism, and build community’.

So these large systems that promise to promote your kind, helpful informative posts, also promote hate-speech and genocide.

But what’s the alternative? Shout into the void?

Actually, Molly White, with more than 20,000 subscribers, wasn’t happy with Substack, and she decided she didn’t want any platform dependence at all, so she rolled her own, and gave detailed instructions for anyone who might want to do the same.

Unfortunately, this isn’t simple. It’s not terribly difficult, but the bar is just high enough that it’s obvious that most people won’t bother. I mean, everyone has principles, don’t they, until the moment they see the phrase, “MySQL wasn’t configured properly”?

I’m not going to help out the haters, but I wouldn’t mind getting a few views, but also I’m not a tech wizard.

It’s a dilemma.

So where online are the people who might find my writing worthwhile? I might have some good reasons to prefer my blog over social media, but that doesn’t mean my audience does. Let’s say I’m writing a post about getting more readers. If I want to help people with this post, I need to think a bit about who it’s for and where these people usually go to get their information.

On reflection, it seems the obscure niche subjects I like writing about are well-suited to online ‘small rooms’ like subreddits, forums and discord groups, rather than ‘big rooms’ like Facebook and TikTok, where ‘context collapse’ is the norm.2

That’s because I’m not posting memes and ‘hot takes’. No goats were surprised by amateur divers in the making of this article. I’m trying to provide thoughtful, eccentric observations for thoughtful (not at all eccentric) readers, so context is everything. This means my interim solution is to post first on my blog, then syndicate where I can, then cross post to small rooms, manually when necessary. It’s a work in progress, but I do seem to be making a little progress.

My book, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters is available right now and it’s selling fine, even though it’s a niche subject and I’m a marketing team of one.

A second reason I’m keen on my own website is that it’s a way of keeping a record of the canonical version of my online writing. The big platforms can just disappear overnight, taking everything with them as they go. Disappearance is also part of business as usual for social media. For example, Pew Research found that in 2023, 1-in-5 (20%) English language tweets had become inaccessible just three months after posting on Twitter (now X). I’d prefer to have some control over the longevity of my work. That’s why syndication is a good plan. Unfortunately, many of the big platforms don’t support it at all. The only way to syndicate is by hand, by copying and pasting. It’s feasible (I do this occasionally with Reddit), but not very efficient.

This matters because the way we organise our online lives bleeds into the way we organise the rest of our social interactions. If it’s just assumed without question that the online space is a fiefdom, then democracy everywhere is undermined.

For wise words on this subject, read Governable Spaces, by Nathan Schneider.

OK, so I know what I’m doing here (at least in one sense of that phrase), but what about what you should do? One piece of advice I do have is to notice how many people actually are reading, listening to or watching your stuff. Really notice. It might be a room-full, or a stadium-full. Every one of your readers, listeners or viewers has spent precious time and effort to engage with your thoughts, and whether or not it pays your bills, that’s amazing and worth pausing a moment to appreciate.

So here’s the point where we pause for a moment to appreciate the wonder that anyone at all is noticing our stuff.

Wow.

But unfortunately that’s all the advice I can give right now. Yes, I’d like to think niche blogs and Small Rooms still win, but that surely depends on how you define ‘winning’. I’m probably doing it all wrong. AI is rapidly transforming the whole landscape of discoverability. Organic search is less and less viable when AI summaries are everywhere. Perhaps, as some are prophesying, the humble hyperlink is dead.

So rather than tell you how to reach your readers (as if!), I have a question for you: how do you reach your readers already, right now, and how do you expect to in a near future dominated by lots of AI hype and quite a bit of AI reality?

What’s changing for you? Are you pumping up the paddling pool right now in preparation for a pivot to YouTube and massive fame? Would you still write if you had a single reader? And do you appreciate the readers you do have?

Oh, it turns out I have quite a few questions.

For still more questions and precious few answers, subscribe to the weekly Writing Slowly email digest.

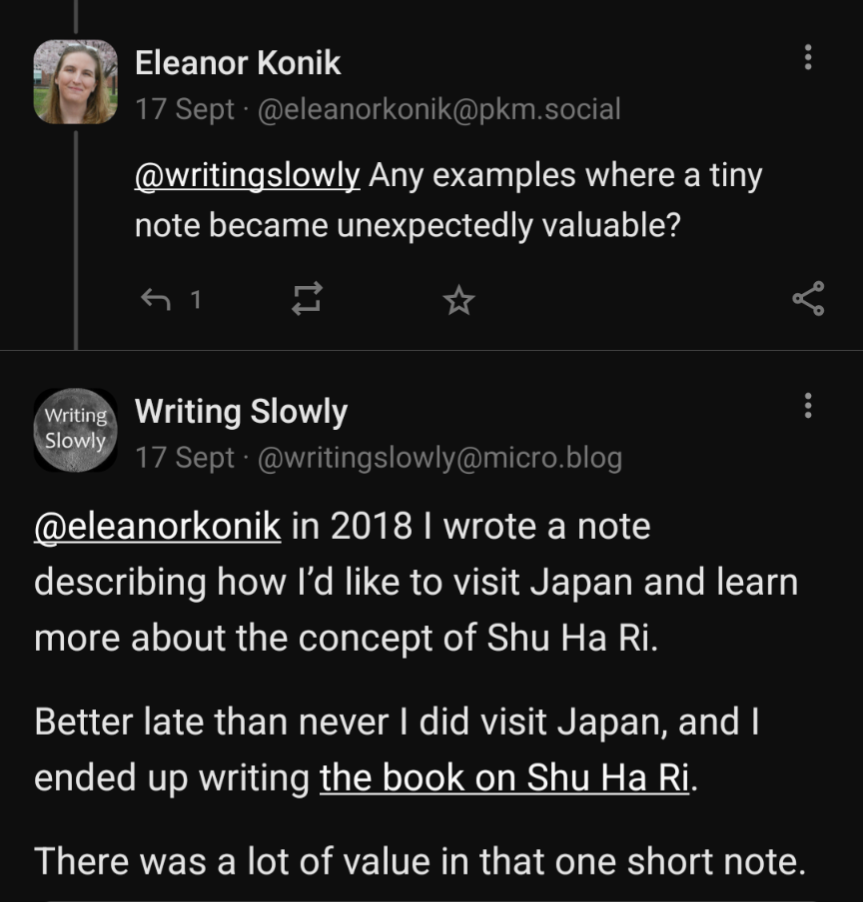

What’s your most valuable note?

@eleanorkonik@pkm.social asked:

“Any examples where a tiny note became unexpectedly valuable?”

Here’s my reply.

In 2018 I wrote a note describing how I’d like to visit Japan and learn more about the concept of Shu Ha Ri.

Better late than never I did visit Japan, and I ended up writing the book on Shu Ha Ri.

There was a lot of value in that one short note.

Create your own mental models

When he was still in high school my cousin took to pulling old cars apart, completely, then putting them back together. This was a real learning experience, and the beginning of an entire career working with motor vehicles. François Chollet, author of Deep Learning with Python, said:

💬 To really understand a concept, you have to “invent” it yourself in some capacity. Understanding doesn’t come from passive content consumption. It is always self-built. It is an active, high-agency, self-directed process of creating and debugging your own mental models. - as quoted by Simon Willison.

This is what I’m doing with my collection of working notes, my Zettelkasten. I disassemble ideas and concepts, de-contextualise them, and reassemble them into new arrangements under quite different circumstances. From fragments you can build a greater whole.

Sometimes ‘invention’ is mashing together two or more existing ideas in new and unexpected ways. But sometimes it’s simply rebuilding an existing idea from the ground up, to create something previously unimaginable.

I wrote my book about the Japanese concept of learning, Shu Ha Ri, because in the fifteen years since I first encountered this concept, no one else had written a clear introduction. It’s quite literally the book I wanted to read for myself. Well, I certainly didn’t invent the idea, but in writing the definitive introduction I’ve certainly taken it apart, examined it from every angle, worked out how to explain it to others, and put it back together.

On Friday I received a nice text from a martial arts instructor, who’d been handed the book by someone else:

💬 I absolutely loved it. First time in a long time I immediately reread a book.

And so I hope you’ll enjoy giving the book a test drive too.

Photo by Geoff Charles, 1962. National Library of Wales. Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru / The National Library of Wales on Unsplash

Photo by Geoff Charles, 1962. National Library of Wales. Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru / The National Library of Wales on Unsplash

Check out my book, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters. And you can also subscribe to the weekly Writing Slowly email newsletter.

Publishing means no more hiding

Revelation must be terrible, knowing you can never hide your voice again. – David Whyte

Publishing my book, I had the strange feeling of having crossed an invisible but very powerful threshold.

It was while signing copies at a small and very supportive gathering, that it dawned on me that the thoughts that used to be just in my head are now public and exposed to the world – and since I’ve lodged this work in every State Library in Australia, they’ll never again be totally private.

I had thought I just wanted to publish my words, to release my book into the wild, as it were, to allow it to find its readers.

So it never occurred that I might have been benefiting in some way from the obscurity of the drafting process.

Not that I want to hide my voice – far from it.

Nor that I’m expecting a million readers. Again, far from it.

But the knowledge that I now have one unique reader – you – with whom my words will perhaps connect whether I bid them or not, well that changes things somehow.

And it’s certainly a revelation to realise there’s no going back.

My book, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, is out now. Please check it out.

I fell down a rabbit hole writing about Hypercuriosity! 🤯 Inspired by Anne-Laure Le Cunff’s work.

Read how being curious about everything defines my process: https://writingslowly.com/2025/09/30/curious-about-hypercuriosity.html

#Hypercuriosity #Curiosity #ADHD #Writingslowly

Having written about the need to create your own writing environment, I found this post showing the writing spaces of 12 Booker Prize nominees quite illuminating. Each one seems like a small but mighty theatre stage (HT: kottke.org).

#WritingCommunity #AmWriting #WritersLife #WritingTips

Curious about Hypercuriosity

One reason I make notes and write is that I’m curious about everything.

I’ve written previously about how to be interested in everything. And I’ve also written about busybodies, hunters and dancers - three different styles of curiosity.

It was the ‘dancer’ style of curiosity that resonated most with me:

“This type of curiosity is described as a dance in which disparate concepts, typically conceived of as unrelated, are briefly linked in unique ways as the curious individual leaps and bounds across traditionally siloed areas of knowledge. Such brief linking fosters the generation or creation of new experiences, ideas, and thoughts.”

So I was interested to see that Anne-Laure Le Cunff, author of Tiny Experiments and founder of Ness Labs, Has been exploring what she calls ‘hypercuriosity’, which may be associated with ADHD.

Well, I guess I’m the living proof. I set out this evening to write about my book, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning for Artists and Fighters but I ended up writing about something completely different instead: hypercuriosity.

Come to think of it, that’s how the book got written in the first place, by pursuing my curiosity. And come to think of it, that’s how I do practically everything.

In writing the book I was particularly attracted by the value placed on the Japanese concept of shoshin (初心), ‘beginner’s mind’ - a quality often downplayed in Western contexts, where experts are supposed to already know everything.

I’m more interested in not knowing - and then going to great lengths to find out.

Links:

Brar, G. (2024, November 14). The hypercuriosity theory of ADHD: An interview with Anne-Laure Le Cunff. Evolution and Psychiatry (Substack).

Gupta, S. (2025, September 16). People with ADHD may have an underappreciated advantage: Hypercuriosity. Science News.

Le Cunff, A. (2024). Distractability and impulsivity in ADHD as an evolutionary mismatch of high trait curiosity. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 10, 282.

Le Cunff, A. (2025, July 15). When curiosity doesn’t fit the world we’ve built: How do we design a world that supports hypercurious minds? Ness Labs.

If you’re curious to catch the latest Writing Slowly action, please subscribe to the weekly email digest. All the posts, delivered straight to your in-box.

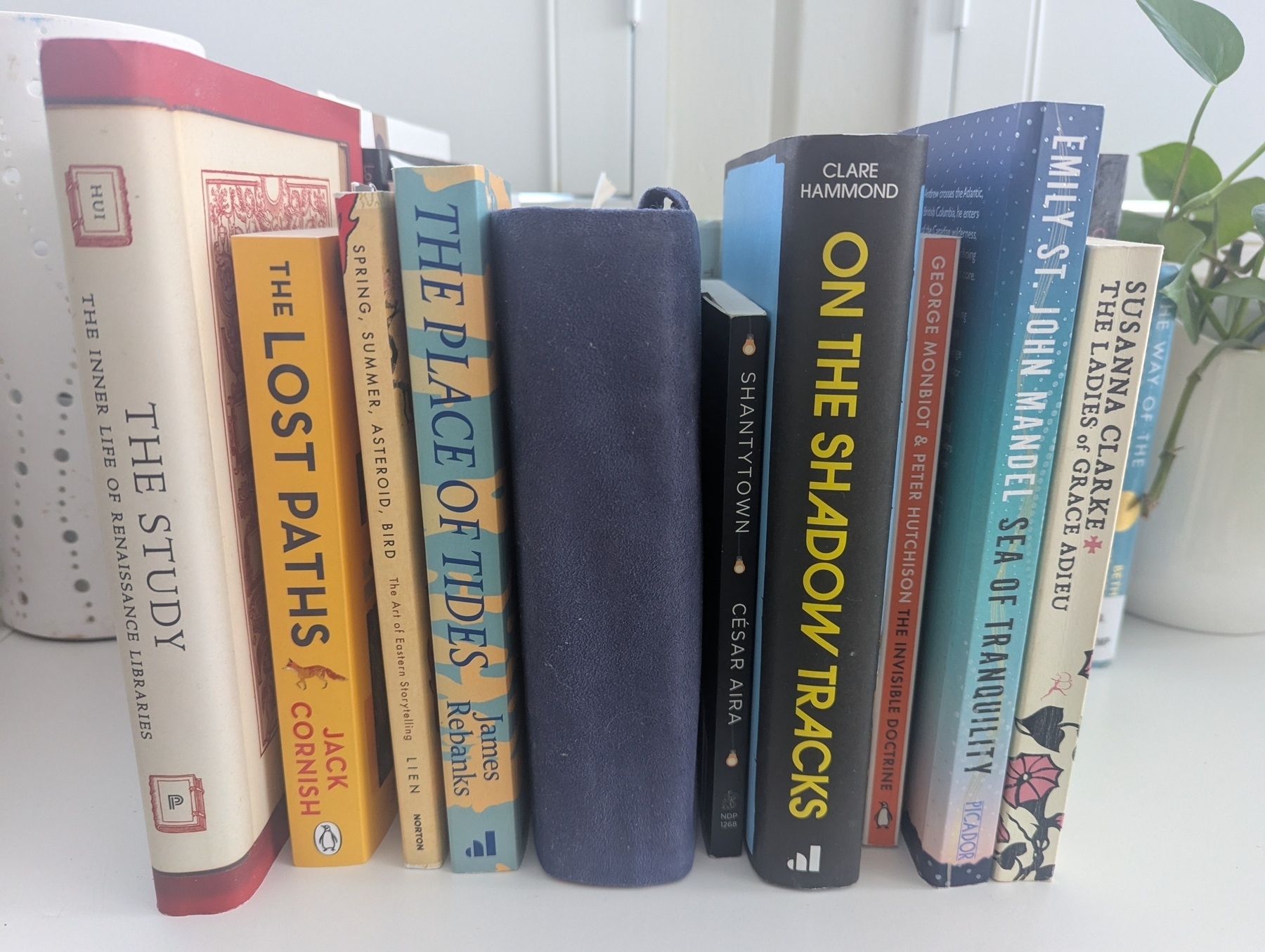

📚Tsundoku emergency temporarily averted.

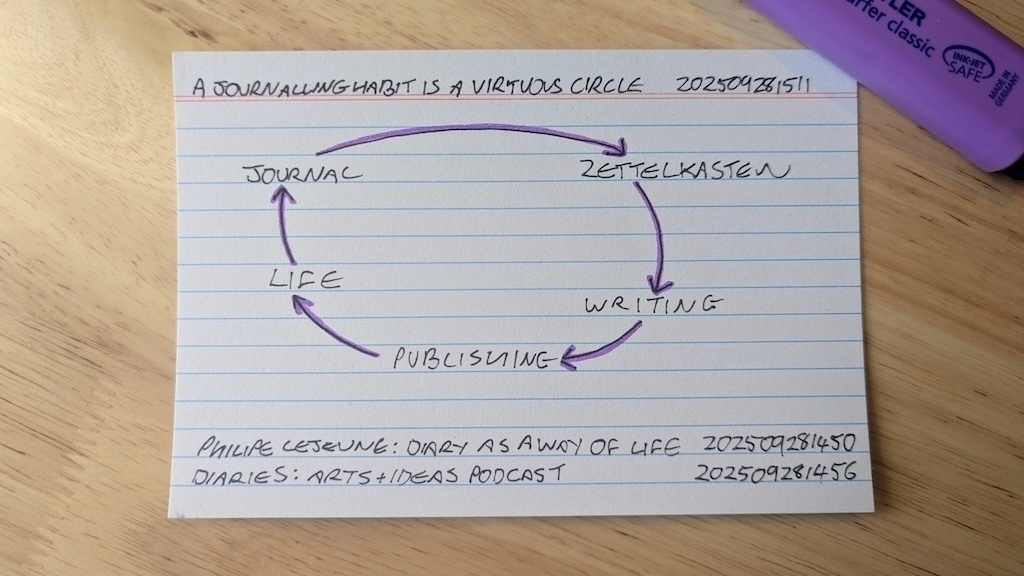

Keeping a diary is a way of living

“A diary is not only a text: it is a behaviour, a way of life, of which the text is a by-product" - French theorist Philipe Lejeune. Source: Arts & Ideas Podcast.

Exactly so. I have a journalling habit, which fuels my Zettelkasten, (my collection of linked notes), which in turn fuels my writing. This in turn affects my life, which I journal about. It’s a virtuous circle.

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters.

And did you know you can sign up to the Writing Slowly weekly email digest?

Zettelkasten podcast episodes

Here are a couple of podcast interviews where the Zettelkasten approach to making notes is discussed in detail. Enjoy!

William Wadsworth (Exam Study Expert) interviews Sonke Ahrens, author of How to Take Smart Notes. Apple Podcasts.

Sönke Ahrens on Niklas Luhmann’s writing process:

“The main part of the writing process happened in this in-between space most people, I believe, neglect. They write notes, they read, they polish their manuscripts, but I think few people understand the importance of taking proper notes and organising them in a way that a manuscript, an argument, a chapter can evolve out of that.”

Jackson Dahl (Dialectic) interviews Billy Oppenheimer, Ryan Holiday’s research assistant, on staying attuned for clues. Apple Podcasts.

“I adopted/adapted Ryan Holiday’s notecard system, which he learned from Robert Greene. And it’s just literally boxes of 4x6 notecards. I’ve never seen Robert’s actual cards, but I have seen Ryan’s. His are filled with shorthands: a maybe a phrase, a word, or a single sentence that conveys a story from some book. They are little reminders capturing the broad strokes of something. You notate it with the book and page number so you can go back and find the specific details.”

“Niklas Luhmann also has another great idea about making notes for an ignorant stranger… Because that’s what you are when you come back to it. We think, “There’s no way I’m going to forget this story.” You come back to it, and it’s highlighted and underlined. You’re like, “What was I loving about this?” I try to make the note cards for an ignorant stranger. You should be able to pick one up and have enough context to make out what this thing is. And so in a similar way, in the margins of books, I try to do that for myself.”

An atomic note isn’t just about ideas; it’s about time. Start smaller, stop sooner, and your notes become easier to reuse and connect. ✍️ Post here: The shortest writing session that could possibly work.

#NoteTaking #KnowledgeWork #zettelkasten #writingtips

Back to the Information City? How knowledge visualisation shapes the journey

I was intrigued by Mark Bernstein’s1 co-authored article revisiting the concept of the city as a visual metaphor for information in the era of hypertext.

Intrigued, because I’m not convinced the city makes things clearer. In fact the first thing that came into my mind was Steven Marcus’s claim from way back that urban dwellers experience a particular kind of estrangement. They sense that “the city is unintelligible and illegible”. This appears in a collection of essays on the Victorian city, in an essay titled ‘Reading the Illegible.’ (1973:257).

This idea - that the city can’t be read - put me in mind of Jonathan Raban’s proto-postmodernist book Soft City (1974), where he contrasts the book with the city, the legible with the illegible.

“The city and the book are opposed forms: to force the city’s spread, contingency, and aimless motion into the tight progression of a narrative is to risk a total falsehood. There is no single point of view from which we can grasp the city as a whole. That indeed is the distinction between the city and the small town. A good working definition of metropolitan life would center on its intrinsic illegibility. (p. 219)

As it happens, it seems that the article authors' conclusion is that the Information city is not a particularly promising metaphor to guide the navigation of complex information structures:

“It seems clear that the Information City is better suited to constructive than to exploratory hypertext.”

This ties in nicely with my take on anthropologist Tim Ingold’s view that creativity is more about ‘itineration’ (wayfinding) than ‘iteration’ (making an object).

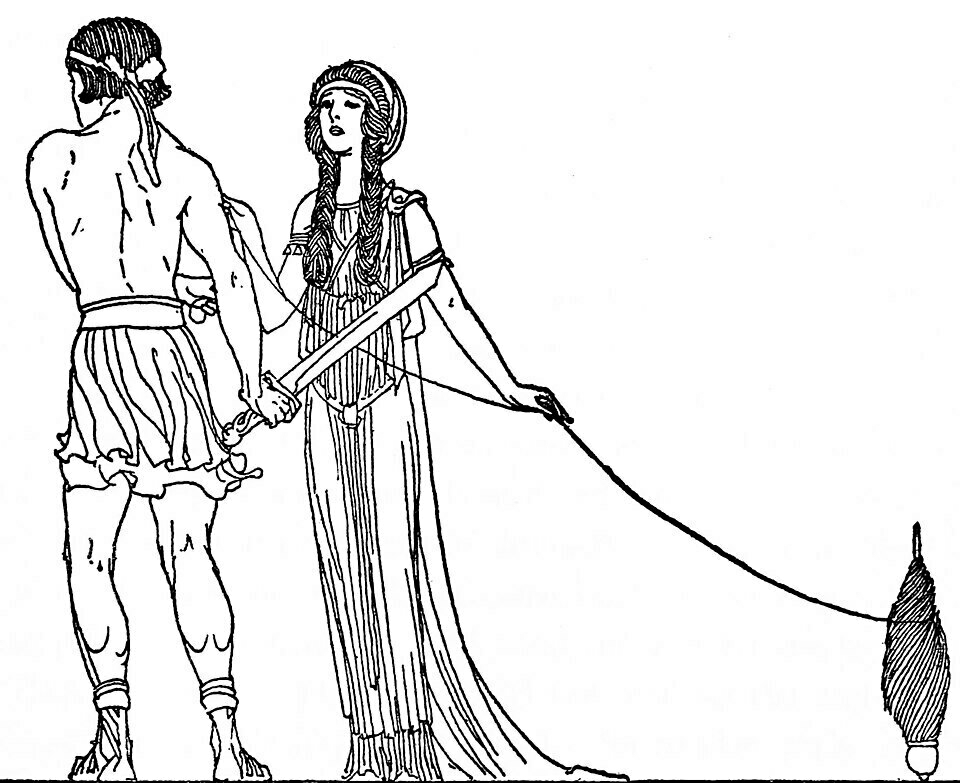

Would it be possible, then, somehow to depict the wayfinding process in and of itself without in advance also reifying the landscape? I’m imagining a walk through an unfamiliar place, which through repetition gradually becomes familiar, and may be rendered yet more familiar by establishing idiosyncratic markers, the way Ariadne’s thread guided Theseus through the Minotaur’s labyrinth.

*[Image source]: Internet Archive Book Images, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons.*

*[Image source]: Internet Archive Book Images, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons.*

The authors say of their attempted information visualisation:

“The Information City may be superb for some and intolerable for those who might prefer to work in a Piranesi dungeon.”

My view is that despite the efforts of UI creators, we don’t really have a choice in this matter. We are already living in Piranesi’s dungeon, in which meaning is lost and found and lost again, and where forgetting is as important as remembering.

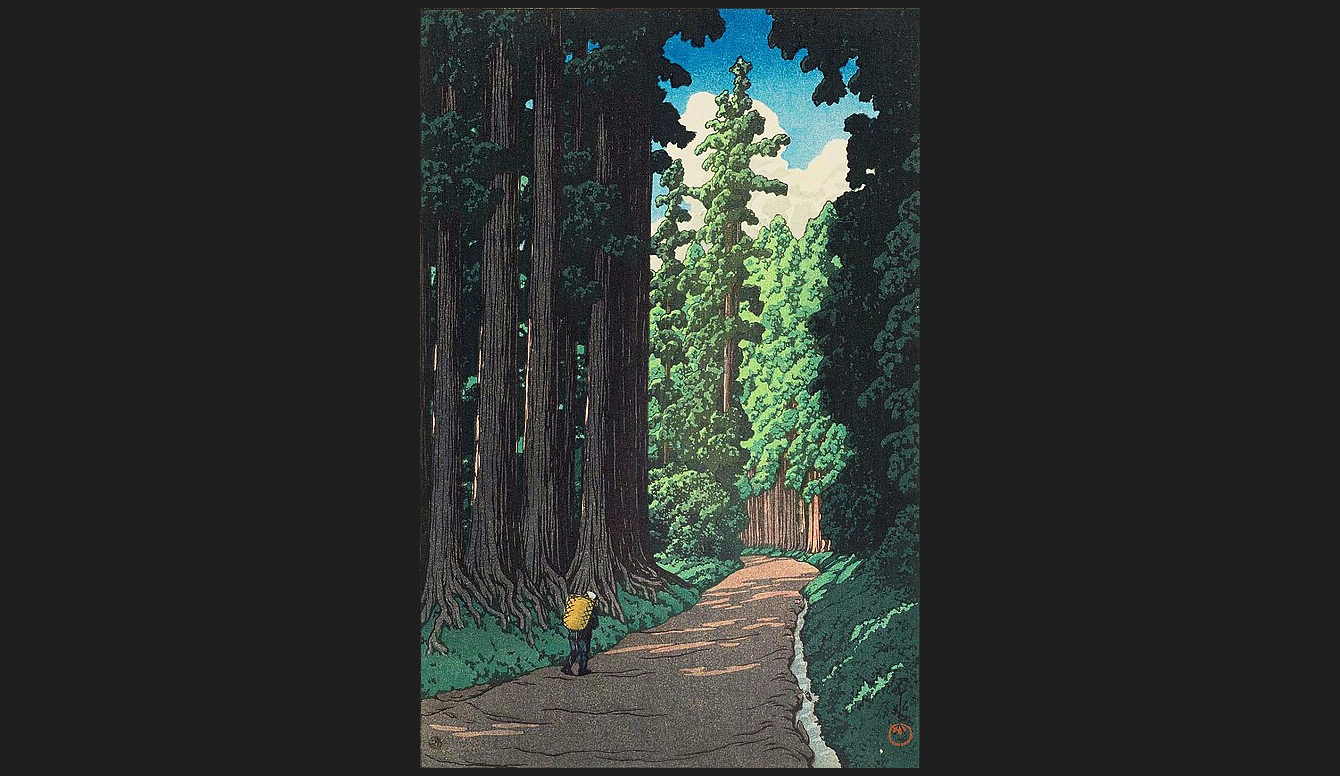

That said, I’m as wary of the dream of information legibility as I am of the dream of urban legibility. The metaphor that works for me is of an immense and unknown forest, the deep forest of accumulated knowledge. Though travelers may have no sense of the ultimate extent of the forest, and even if there is no thread, they can make one as they explore. They may still provide a report, like a travel journal:

“Here is the route I took, and here are the landmarks I discovered on the way.".

This deep subjectivity allows for a limited form of objectivity:

“with my report in hand you too can follow this path through the trees.".

*[Image source: Hasui Kawase], Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.*

*[Image source: Hasui Kawase], Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.*

References:

Bernstein, Mark, Silas Hooper, and Mark Anderson. “Back to the Information City.” Paper presented at HT 2025: 36th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media, Chicago, IL, September 15–18, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1145/3720553.3746664.

Dyos, H. J., and Michael Wolff. The Victorian City: Images and Realities. Vol. 1. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1973.

Ingold, Tim. “The Textility of Making.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34 (2010): 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bep042.

Raban, Jonathan. Soft City: The Art of Cosmopolitan Living. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1974.