How to connect your notes to make them more effective

A linked note is a happy note

A great strength of the Zettelkasten approach to writing is that it promotes atomic notes, densely linked. The links are almost as valuable as the notes themselves, and sometimes more valuable.

But once you’ve had an idea and written it down, what is it supposed to link to? Is there a rule or a convention, or do you just wing it?

How are you supposed to make connections between your notes when you can’t think of any?

When I started creating my system of notes I didn’t know how to make these links between my atomic ideas, and this relational way of working didn’t come naturally to me. I would just sit there and think, “what does this remind me of?” Sometimes I’d come up with a new link, but more often than not, I didn’t. The problem is, the Zettelkasten pretty much relies on links between notes. An un-linked note is a kind of orphan. It risks getting lost in the pile. You wrote it, but how will you ever find it again? And if you do somehow stumble upon it again, it won’t really lead anywhere, because you haven’t related it to anything else.

Fortunately, there are some helpful ways of coming up with linking ideas that can really aid creative thinking and unlock the power of connected note-making.

Make a path through your notes with the idea compass

Niklas Luhmann, the sociologist who famously (to nerds) kept a Zettelkasten, didn’t exactly say this, but each atomic note already implies its own series of relations. Each note can be extended by means of the idea compass - a wonderful idea of Fei-Ling Tseng, as follows:

- N - what larger pattern does this concept belong to?

- S - what more basic components is this concept made of?

- E - what is this concept similar to?

- W - what is this concept different from?

Notice how the first two questions promote a tree-like hierarchical structure, with everything nested in everything else, while the second two questions promote a fungus-like anti-hierarchical structure, with links that form a rhizome or lattice. Alone, the former structure is too rigid and the latter is too fluid. But put them together and they can be very powerful. The genius of the Zettelkasten system is that it absorbs hierarchical knowledge networks into its overall rhizomatic structure, without dissolving them, and allows new structures to form (Nick Milo helpfully calls these ‘maps of content’).

Find the larger pattern

Each atomic idea might be thought of as part of a larger pattern. In a sense, every note title is just an item in a list that forms a structure note at a level above it. Say I write a note on ‘functional differentiation’. I realise that this is just one component of a structure note that also includes ‘social systems’, ‘communication’, ‘autopoeisis’ and so on. I write this list, call it ‘Niklas Luhmann - key ideas’, and link it to my existing note. Now I have some ideas for some more notes to write. But will I write them all? No - I’ll only pursue the thoughts that actually interest me, or seem essential. The rest can wait for another day. Actually, I’m suddenly intrigued by what you could possibly have instead of functional differentiation (i.e. what is this note different from?), so I write a new note called ‘pre-modern forms of social structure’ - and link it back to my ‘functional differentiation’ note.

Look for the basic components

Going even further, the atoms, which seemed to be the smallest unit, turn out to be made of sub-atomic particles and so on, all the way down to who knows what (well, particle physicists might know, but I don’t). That means each atomic idea is really just the title of a structure note that hasn’t been written yet. So I take a new note and write: ‘Functional differentiation - the key points’. I imagine this new structure note to be like a top-ten list of important factors, each one ultimately with its own new note - but I’m not going to force myself to write about ten things that don’t matter, just what I find interesting.

When making links, trust and follow your own interest

It’s really important that you don’t try to answer all four questions with a new link. You’re not creating an encyclopedia. Instead, you should only make the connections that actually matter to you. The trace of your own inquisitiveness through the material is, in itself, important information. If it doesn’t matter to you, don’t write about it! Since the notes are atomic, and the possible links increase exponentially (?) the possibility space you are opening up is almost infinite and it can feel overwhelming. So just go with the flow. The key is to find your own curiosity and run with it. That way (as I’ve said before):

-

you’ll write worthwhile notes that address your own questions and

-

this hook of curiosity will help you remember as you learn.

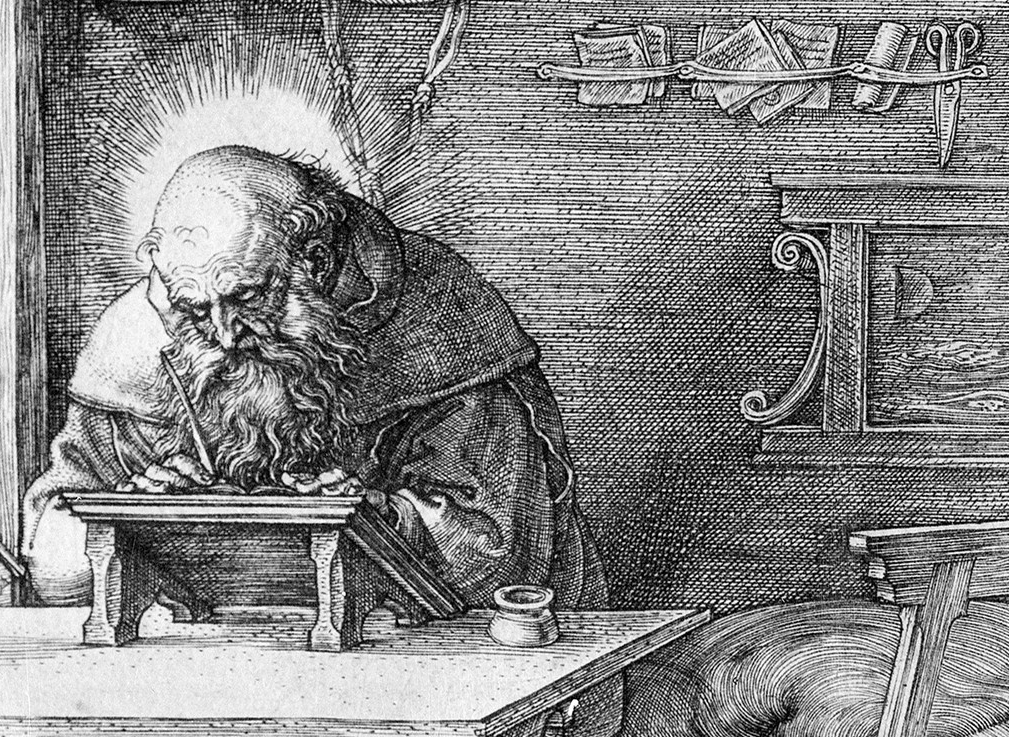

That’s what I’ve been doing this morning. At no point have I stopped to think “what shall I write next?” In this sense, the Zettelkasten is a kind of conversation partner. Niklas Luhmann said he only ever wrote about things that interested him. This seems unlikely until you try it for yourself.

And if you keep asking yourself these questions, you’ll find that over time the linking starts to come naturally. It will be increasingly obvious to you what relationships matter. The questions in the idea compass will become intuitive and fade into the background. Well, that’s my experience, but YMMV.

Apply a framework that intrigues you

Another way of making connections, besides the idea compass, is to apply a conceptual framework (or mental model) that interests you - and see where it leads. Here’s an example: Marshall McLuhan’s tetrad of media effects.

The idea here is that any new technology changes the whole landscape or ecology, by bringing some features into the foreground and pushing others into the background. It’s called a tetrad because there are four questions to ask of a new technology:

-

What does the medium enhance?

-

What does the medium make obsolete?

-

What does the medium retrieve that had been obsolesced earlier?

-

What does the medium reverse or flip into when pushed to extremes?

(This really clicked for me when I puzzled over why my kids don’t use smart phones for talking to people. It seemed crazy to me, but then I looked at question 3 and realised the new technology had retrieved asynchronous communication, which the telephone had previously made obsolete. But I digress.)

Anyway, I’m suggesting you might be able to take these four questions and ask them of the ideas in your notes. For each atomic note: what does this idea enhance, make obsolete, retrieve, or reverse?

Another simple but powerful example is Tobler’s law: “I invoke the first law of geography: everything is connected to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things”. What would it be like if you made everything about physical location?

It’s important to say these are just examples, and they may not work for you. Nevertheless, you may be able to think of frameworks from within your own line of work that allow you to ask a similar set of questions about your ideas. In my experience these frameworks are everywhere and yet are quite under-used.

This article is a lightly edited version of a Reddit comment.

You might also like to read about how a network of notes is a rhizome not a tree.