Atomic Notes

-

Leonardo da Vinci, whose notes were “a collection without order”;

-

Leibniz, who created a haystack of notes (oh, and calculus);

-

Aby Warburg, who suffered from Verknüpfungszwang - the compulsion to find connections; and

-

Hermann Berger, a Swiss author who wrote a novel about a Zettelkssten (two actually) but didn’t publish it.

-

Then there’s cultural theorist Walter Benjamin, who invented a whole new methodology for his Arcades Project, which he didn’t finish. Wikipedia. He’s certainly a candidate for unqualified posthumous ADHD diagnosis.

- Austin Kleon, interview on The Echoes Podcast, 10 June 2025.

I’m unqualified to diagnose the following writers with ADHD but I’ll do it anyway

Yes indeed: confidently diagnosing deceased note-making writers with ADHD, while in possession of no medical qualifications myself, is a temptation I simply cannot resist.

For example I have wondered about:

As I said, it’s interesting, but for now I’ll stop there.

—-

This post started life as a comment on Reddit. If you’d like more from me, but in a weekly email, why not subscribe right now?

💬 “The things that make us different, in the right context are superpowers. You know, Saul Steinberg said the thing that we respond to in any work of art is the struggle of the artist against his or her limitations.”

This makes me feel like there’s an awful lot of wrong context lying about. I guess we all need to find a place where we can thrive, or else make it ourselves.

The original quote is from Kurt Vonnegut’s recollection of a conversation with Saul Steinberg.

#creativity #writerslife #deepthoughts #inspiration

💬 Most attempts at providing computerised tools for writers have thrown out the affordances that previous analogue systems offered, almost without noticing their loss. - writingslowly.com on Ted Nelson’s evolutionary list file.

“Sometimes it’s just nice to know there are other people out there quietly thinking things through.” - writingslowly.com

Don't let your note-making system infect you with Archive Fever

The Zettelkasten note-taking system offers a structured approach to organizing thoughts but might induce “archive fever,” which may lead to an obsession with preservation over actual writing. Here’s how to protect yourself.

📷 Photo challenge day 25: decay.

My worm farm is amazing! By turning waste into compost these little wrigglers perfom a kind of magic.

It’s also a metaphor for my writing process. I don’t worry if the input is rotten. The output will be quite different.

See also: No writing is wasted

Don’t throw away your old notes

Don’t throw out your old notes, even if you feel overwhelmed by them. Here are some helpful ideas on what to do instead.

What to do when you've made some notes: Start writing

The next step after taking notes is to create a finished piece of writing, acknowledging that the first draft may be disorganized but serves as a foundation for improvement.

What I Learned from Bob Doto about Making Effective Notes and Writing a Book

Historian Dan Allosso led a discussion on Bob Doto’s insights on flexible note-taking and writing processes. It emphasised the importance of iterative development and audience engagement. Here are my notes.

Influence is everything: novelty its flimsy dress

This whole article dumbed down by AI summary: Cultural trends often leave behind valuable ideas that merit revisiting rather than being dismissed as unfashionable. And I thought I was being clever.

💬"When you’re writing, you’re trying to find out something which you don’t know. The whole language of writing for me is finding out what you don’t want to know, what you don’t want to find out. But something forces you to anyway." - James Baldwin. Paris Review, The Art of Fiction No. 78. no. 91, 1984.

A search for meaning in the palace of lost memories: Thoughts on Piranesi, a novel by Susanna Clarke

Susanna Clarke’s novel Piranesi has got me thinking about memory, identity, the fallibility of writing, and the paradox that intrinsic value might be created rather than found

💬 “There’s a left-field way of thinking about the world that doesn’t follow the straight path. The route forward doesn’t have to lead in one true direction but potentially many.”

Non-linear narratives inspire non-linear notes.

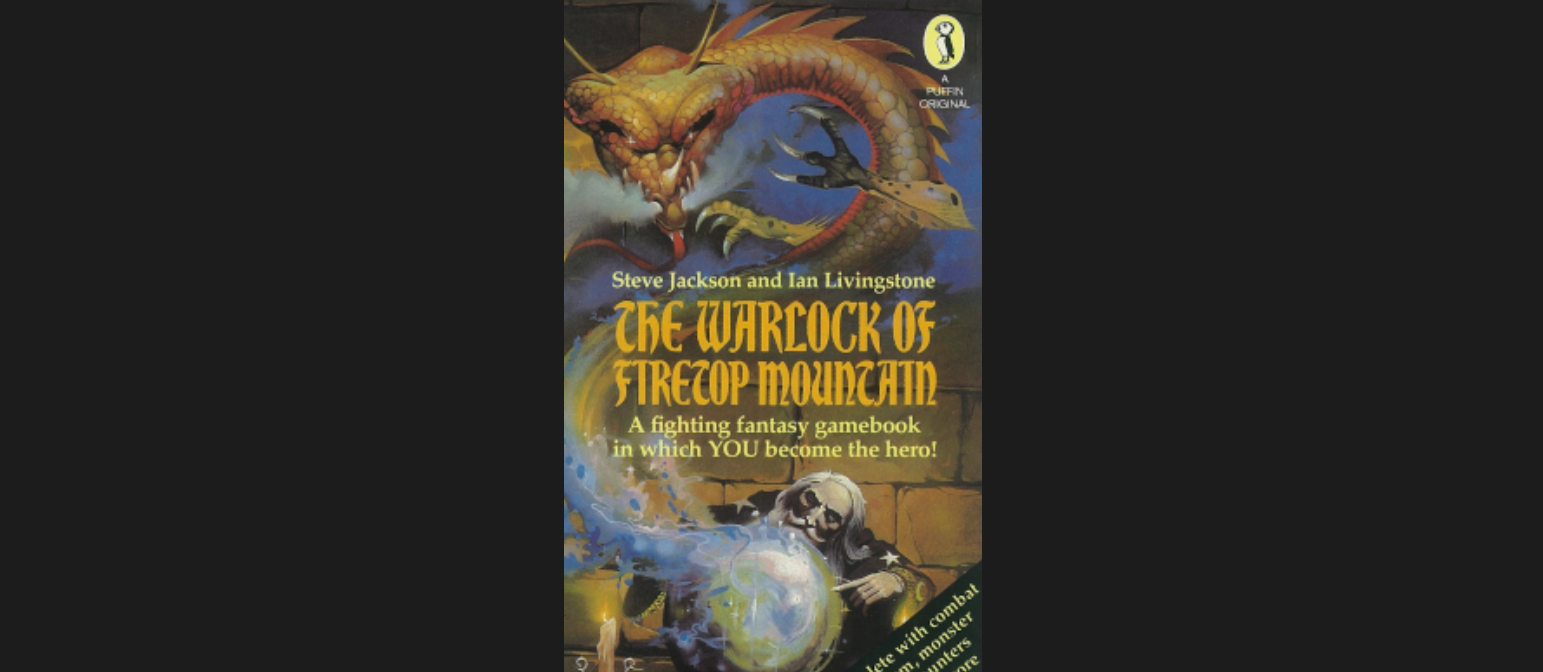

What I've learned from non-linear narratives

Thoughts on how non-linear narratives have profoundly influenced my reading and writing practices, allowing for a more organic and interconnected approach to storytelling and knowledge creation.

When did you first hear about making notes the Zettelkasten way?

#pkm #zettelkasten #notetaking

Daniel Wisser’s notecards as art and archive

Daniel Wisser’s exhibition in Vienna features 60 index cards with sketches of stories displayed in a note box (Zettelkasten).

What Tim Berners-Lee Has to Teach About Effective Notes

Tim Berners-Lee’s insights on the interconnected nature of knowledge have inspired a flexible, web-like approach to note-making that mirrors my natural thinking rather than some restrictive categorization.

“The rapid passage of time is a complete antimeaning machine. Doesn’t life absolutely require tactical slowing down if a person, even a smart, serious, concerned one, is to find the time and space to make meaning?” - Eric Maisel

Tactical slowing down is great, but then writing slowly is a whole strategy.

Leibniz created a haystack of notes that wouldn't fit in his Zettelschrank

Gottfried Leibniz, a prolific yet disorganized thinker, struggled to manage an overwhelming influx of ideas, resulting in a vast but minimally published literary legacy. Is this a cautionary tale or some other kind of tale? I have an opinion.

Sinister Zettelkasten?

The 2025 Sydney Film Festival program features Jodie Foster’s new film, “Vie privée,” accompanied by a marketing image that evokes mystery with index card boxes in the background.