Learning to make notes like Leonardo

Leonardo wrote on loose sheets of paper

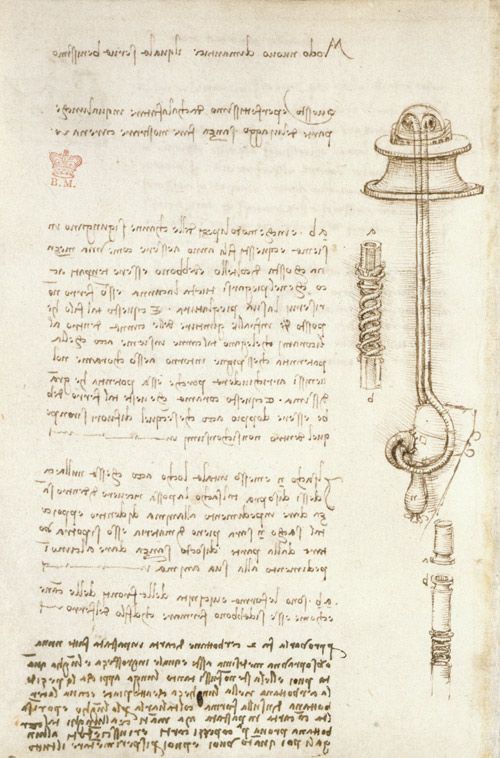

The Codex Arundel, a notebook of Leonardo Da Vinci, is not what it first appears. It isn’t a notebook that Leonardo used. For the man himself it wasn’t a notebook at all. It’s a collection of individual notes, bound for convenience only after his death. The British Library webpage observes:

“The structure of the notebook reveals that it was not originally a bound volume. It was put together after Leonardo’s death from loose papers of various types and sizes, some indicating Leonardo’s habit of carrying smaller bundles of notes to document observations outdoors.”

He wasn’t the first to adopt this habit. Beginning in the Fourteenth century it had become something of a fashion for Italians to create their own ’zibaldone’, a hodgepodge of notes on diverse subjects. Leonardo wrote of his notes:

“This is to be a collection without order, drawn from many papers, which I have copied here, hoping to arrange them later each in its place, according to the subjects of which they treat.”

The same is true of the Forster Codices, in the care of the Victoria and Albert Museum: they weren’t originally codices (books), but unbound notes.

“Leonardo probably worked on loose sheets of paper (bought at one of Milan’s many stationers' shops), which he carried about with him to record his observations. His papers were at some stage folded into booklets and later bound, possibly under the ownership of the Spanish sculptor Pompeo Leoni (1533 – 1608).” (https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/leonardo-da-vincis-notebooks)

Many of the notes in the Codex Arundel were written in 1508, but they span most of Leonardo’s career.

The notes cover a very wide range as well as references to many different subjects. They include sketches of a mechanical organ and of an underwater breathing apparatus, There are notes and diagrams on mechanics, lists of proverbs and riddles, sketches on bird-flight, a household inventory, notes on optics and mirrors for producing heat, calculations on balances and weights, a plan for an urban quarter, and for a complete city, notes on the acoustics of drums and wind instruments, notes on river dynamics and on geometry, and a sketch of a cockleshell.

Leonardo Da Vinci - master of making notes

Here’s the German scholar Hektor Haarkötter, writing about the note-making expertise of Leonardo Da Vinci:

“Leonardo is the early master of the note [Nottizettel]. Today da Vinci is famous as an artist and painter, inventor and designer. However, he was not very productive as a public artist. Only about fifteen paintings that can be proven to have been created by him have survived, some of them in very poor condition or never completed. Leonardo da Vinci was really productive, however, in the privacy of his writing. He left behind over 10,000 sheets, drafts, scraps, snippets, sketches, papers, pages and slips of paper. (Many have been transcribed in Theodor Lücke, Leonardo da Vinci. Tagebücher und Aufzeichnungen. Leipzig, Paul List Verlag, 1953)

And this is only the part of his many records that have come down to us. Through his papers we know of other ledgers, notebooks, and codices, but they have disappeared, been scattered, torn apart, sold off, or in one way or another through the course of time, simply destroyed. How large the number of those records is of which we have no, well, note, is incalculable.

Already in Leonardo’s work all the characteristics of the note [Nottizettel] as a private medium are visible. He wrote in a code so that unauthorized eyes could not have read his notes. The universality of writing materials and forms of writing corresponded the universality of the subjects. From word lists and shopping wishes to technical drawings and philosophical notes to obscene and pornographic sketches. None of them was intended for the public, and the Renaissance master never published a book. He would hardly have been able to do so, he admitted to himself in his notebooks, which today are traded at astronomical prices at auctions, but which themselves lost an overview of his records.

What remains?

The amazing thing about the inconspicuous medium of notes is that from a hodgepodge of notes in the writing practice of writers and scientists, a completed book can emerge in the end. However we must not forget that, as a rule, only a small part of the notes, as a preliminary stage, finally ends up in the work. The larger part of such paralipomena [supplementary material, literally ‘things omitted’] remains, is never used, is hardly ever read again, and is often discarded and thrown away. Or the notes end up in the archives, where they are preserved as cryptic manuscripts, in worm-eaten folders or as messy single sheets, where they can enjoy the security of all basement magazines, never again to be viewed by human eyes. Notes are communicants after all without communicating. The path to the finished book is paved with media corpses.”

Source: Hektor Haarkötter, «Ich notiere, also bin ich» Notizen als Medien des Denkens Passim 28 (2021) Bulletin des Schweizerischen Literaturarchivs, p.4-5. Available at: <www.nb.admin.ch/snl/de/ho…> Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator and a bit of imagination.

What can we learn from Leonardo’s approach to making notes?

Write everything down

Make notes. you never know when you’ll invent a diving mechanism, or a flying machine, or who knows what else? Toby Lester, author of Da Vinci’s Ghost, claims, “Whenever something caught his eye he would compulsively open a small notebook that he wore hanging from his belt and begin sketching furiously, with almost mind-boggling virtuosity. He loved his tiny sketchbook and recommended that all serious artists carry one.” “These things should not be rubbed out,” wrote Leonardo, “but preserved with great care, for the forms and positions of objects are so infinite that the memory is incapable of retaining them”. Leonardo plainly wrote (and drew) in order to think - and you can too.

Use your memory too

Don’t expect your note system to remember things for you. There is a view that writing helps you to remember. But Hektor Haarkötter calls this ‘a myth of the media’. “In fact,” he says, “there is hardly a more effective way to erase a thought from memory than to write it down. The problem of remembering is not solved by taking notes, but only delegated, namely from “What did I want to remember?” to “Where did I write it down?” And the larger the volume of notes, the smaller the probability of finding a specific note again.” So making a note is primarily the act of thinking itself, not a primarily a way to remember what you thought.

Do what works for you

Loose leaf pages worked for Leonardo, and he wrote thousands of them. He had a system that enabled him both to think and to capture his thoughts. Don’t wait for the ideal system to appear, when an OK one will do. And don’t over-complicate things. He didn’t have a Moleskine notebook, or Obsidian software. He just wrote.

Don’t put off the organisation for another time

Don’t put it off, because that day may never come.

Leonardo intended “to arrange them later each in its place, according to the subjects of which they treat”, but as far as we can tell, he never did. This is possibly a reference to the then popular practice of arranging notes in ‘loci communis’, or commonplaces - so called because there were several different standard systems of thematic arrangement by category. He didn’t get round to it. And later editors didn’t have much idea of what order to put his notes after he was gone. Who knows what he might have finished if he’d been a bit more organised at the outset. Don’t put off the organisation of your notes, because it will probably never happen.

Publish, by any means necessary

Notoriously, Leonardo hardly finished anything. Some of this, such as the unfinished painting now known as Mona Lisa, may have been deliberate. But on his death, Leonardo left his notes to his faithful pupil Francesco Melzi, who then left them to his son. The son didn’t value them at all and abandoned them to molder in an attic, so it’s amazing any of these now priceless notes survived at all. In fact the reason Leonardo is best known as an artist, which was not his main occupation (in 1482 he put at the very bottom of his resume for the Duke of Milan, “also I can do in painting whatever may be done”), is that the notes were effectively lost for generations and only really came to attention in later centuries. Don’t put off the publishing of your knowledge. Your pupils' children might not follow your instructions any more than Leonardo’s did. Share what you know with others. Don’t expect it to outlive you. Seize the day. You might think you’re no Leonardo. That’s right. You’re not. You are you, and that’s exactly what the world needs.

Furthermore, it’s so much easier to publish these days than it was at the time of Leonardo. There’s hardly any excuse not to press ‘send’.

There might just be a better system

I hesitate to try to improve on arguably the greatest genius of all time, but with the greatest presumption, here goes. Leonardo himself called his notes ‘a collection without order’, and perhaps a modicum of order might heave helped him. The system he never got around to using was that of ‘commonplaces’, extremely widely used during the Renaissance and for centuries after. The idea was that you’d catalogue your notes according to a more-or-less standard set of locations (i.e. common places). There are a few problems here.

First, it’s hard and uninteresting work to catalogue all your thoughts into predetermined folders like this. Perhaps that’s why Leonardo didn’t do it. Maybe it was just not important enough.

Second, even if you do want to file your notes, it’s not universally agreed what the folder names should be. Through the ages there have been numerous attempts to design a standard set of commonplaces, and none of them have stuck. One such is the Dewey Decimal System, often used for cataloguing library subjects. Not even all the libraries follow this particular system. Wikipedia has a list of ‘main topic classifications’, too. Though you might not know this, you probably haven’t suffered from your ignorance on this matter. To the ordinary Wikipedia user, it doesn’t really seem to make much difference.

Third, keeping your ideas in the categories within which they were formed tends to limit innovation and re-combination. For example, a folder of notes labelled ‘psychology’ doesn’t really tell you much and it keeps your psychology ideas artificially separated from your thoughts on art, or sport, or jokes. In fact, any categories tend to damp down the creative spark. Perhaps that’s why Leonardo’s ‘collection without order’ worked for him.

More resources

The Codex Arundel is at the British Library and online.

David Kadavy has a great podcast episode about Leonardo: Leonardo Mind, Raphael World – Love Your Work, Episode 290 Ironically, Kadavy sees Leonardo as ‘the greatest procrastinator who ever lived’. It’s ironic because, well, it’s Leonardo.

Hektor Haarkötter’s book on notemaking includes more on Leonardo as well as a host of other characters, but Notizzettel is currently only published in German.

And if you’ve read this far, you’ll love Gillian Hess’s Substack blog, Noted. She has already written plenty about Leonardo, which you can read by subscribing.

Meanwhile, on this site, I’ve also written about Aby Warburg’s compulsion to make notes, and about Ted Nelson’s evolutionary file list, and about the writing process of Henry Thoreau - and probably lots more about Zettelkasten I’ve forgotten about.