Thoughts are nest-eggs - Thoreau on writing

In October 1837 the writer Ralph Waldo Emerson prompted the twenty-year-old Henry David Thoreau to start writing a journal.

“‘What are you doing now?’ he asked. ‘Do you keep a journal?’ So I make my first entry to-day.”

Thoreau finished up with fourteen full notebooks: seven thousand pages, and two million words. Small fragments can add up to an awful lot. From these fragments he constructed pretty much all of his completed works. What began as jottings ended up as mature reflections.

He claimed his disconnected thoughts provoked others, so that ‘thought begat thought’.

Thoreau wrote in his journal:

“To set down such choice experiences that my own writings may inspire me – and at least I may make wholes of parts.

Certainly it is a distinct profession to rescue from oblivion and to fix the sentiments and thoughts which visit all men more or less generally. That the contemplation of the unfinished picture may suggest its harmonious completion. Associate reverently, and as much as you can with your loftiest thoughts. Each thought that is welcomed and recorded is a nest egg – by the side of which more will be laid. Thoughts accidentally thrown together become a frame – in which more may be developed and exhibited. Perhaps this is the main value of a habit of writing – of keeping a journal. That so we remember our best hours – and stimulate ourselves. My thoughts are my company – They have a certain individuality and separate existence – aye personality. Having by chance recorded a few disconnected thoughts and then brought them into juxtaposition – they suggest a whole new field in which it was possible to labor and to think. Thought begat thought.” – Henry David Thoreau, The Journal, January 22, 1852.

The writer, according to Thoreau, doesn’t have a privileged position in relation to ideas or experiences. Everyone has the same access to their “sentiments and thoughts.” But the writer’s special task is to record them.

Thoreau’s meticulous editing process moved from raw field notes, to his journal, to lectures, to essays, and from there to published books. Walden, for example, was published after seven drafts, which took the author nine years to complete.

“The thoughtfulness and quality of his journal writings enabled him to reuse entire passages from it in his lectures and published writings. In his early years, Thoreau would literally cut out pages or excerpts from the journal and paste them onto another page as he created his essays.” - Thoreau’s Writing - The Walden Woods Project

This pretty much sums up the Zettelkasten approach to note-making for me. Thoreau lays out a simple process for “fixing” one’s thoughts in writing and for making something of them.

- Record your thoughts, one by one.

- “Each thought that is welcomed and recorded is a nest egg…”

- Build up a collection of notes, without worrying about whether they are coherent.

- “…by the side of which more will be laid.”

- Connect your notes, creating a dense network of association.

- “Thoughts accidentally thrown together become a frame in which more may be developed and exhibited

- Construct meaning from your previously disconnected thoughts

- “Thought begat thought.”

Note that the thoughts don’t necessarily follow on from one another. The very next idea Thoreau noted in his journal is on a completely different subject: the colour of the winter sun not long before dusk.

Someone who has found their own distinctive approach to writing that seems to echo that of Thoreau is Visakan Veerasamy. He lives in the 21st Century, not the Nineteenth, and instead of a cabin in the woods he probably has a laptop in a cafe. Instead of field notes he writes using tweets and threads, which he then links together in a dense network of thought.

“I’ve basically taught myself to manage my ADHD with notes and threads."- Visakan Veerasamy

What calls Visakan to mind as I reflect on Thoreau’s writing practice is the sense they both seem to share of the seriousness of the practice of making something from nothing by writing short notes in a journal. Visakan says something of which I’m sure both Thoreau and Emerson would have approved:

in a way journaling for yourself is a radical act! It’s an act of self-ownership, self-education. It’s about setting your own curriculum, defining your own worldview, deciding for yourself what is important. I don’t think this should be outsourced to others.

People tend to think of writers like Thoreau as immensely successful. True he became a popular speaker, but Thoreau was not a successful writer, at least not in his lifetime.

“A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers [1849] was initially an abysmal failure. Henry was forced to take back the books that were not sold, totalling 706 out of the 1,000 originally printed. Writing humorously of the event in his journal, he quipped, “I have now a library of nearly nine hundred volumes, over seven hundred of which I wrote myself” (Thoreau 459). Walden [1854], in contrast, was a relatively successful book, though it took most of the rest of Thoreau’s life to sell the 2,000 books of the first edition.” – Thoreau’s Writing - The Walden Woods Project

This knowledge inspires me to write without too much concern for the outcome, and to focus instead on those aspects of the process that lie within my control - recording my thoughts and like Thoreau turning them into nest eggs.

References:

Thoreau, Henry David. 2009. The Journal, 1837-1861. Edited by Damion Searls. New York: New York Review Books.

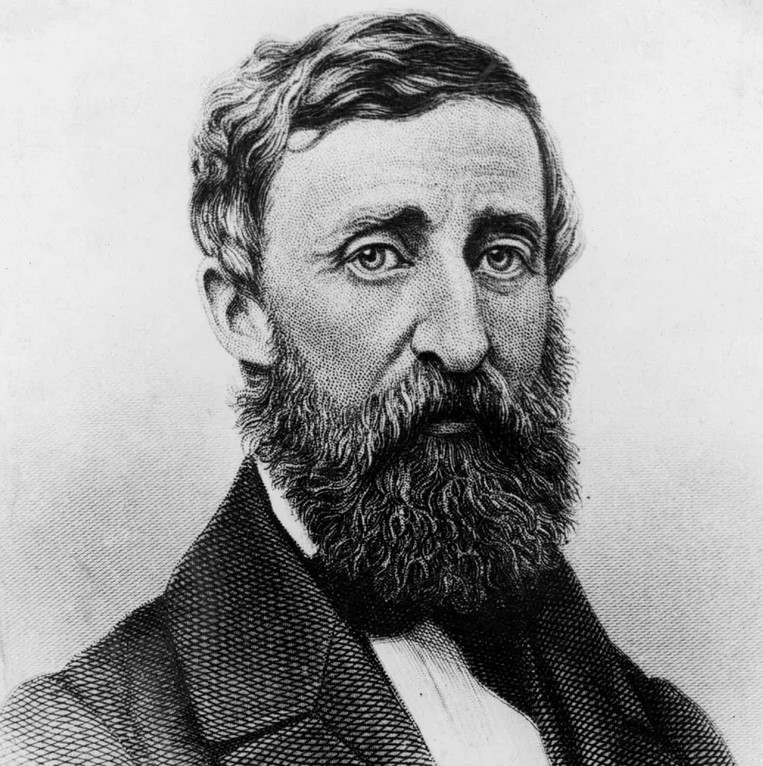

Image of Thoreau suitable for use on currency