Guy Kawasaki says ‘move fast and break things’ is a myth. True! But since he can’t quite escape its toxic allure, I’ll say it for him, loudly and proudly:

Move slow and fix things. [guykawasaki.substack.com]

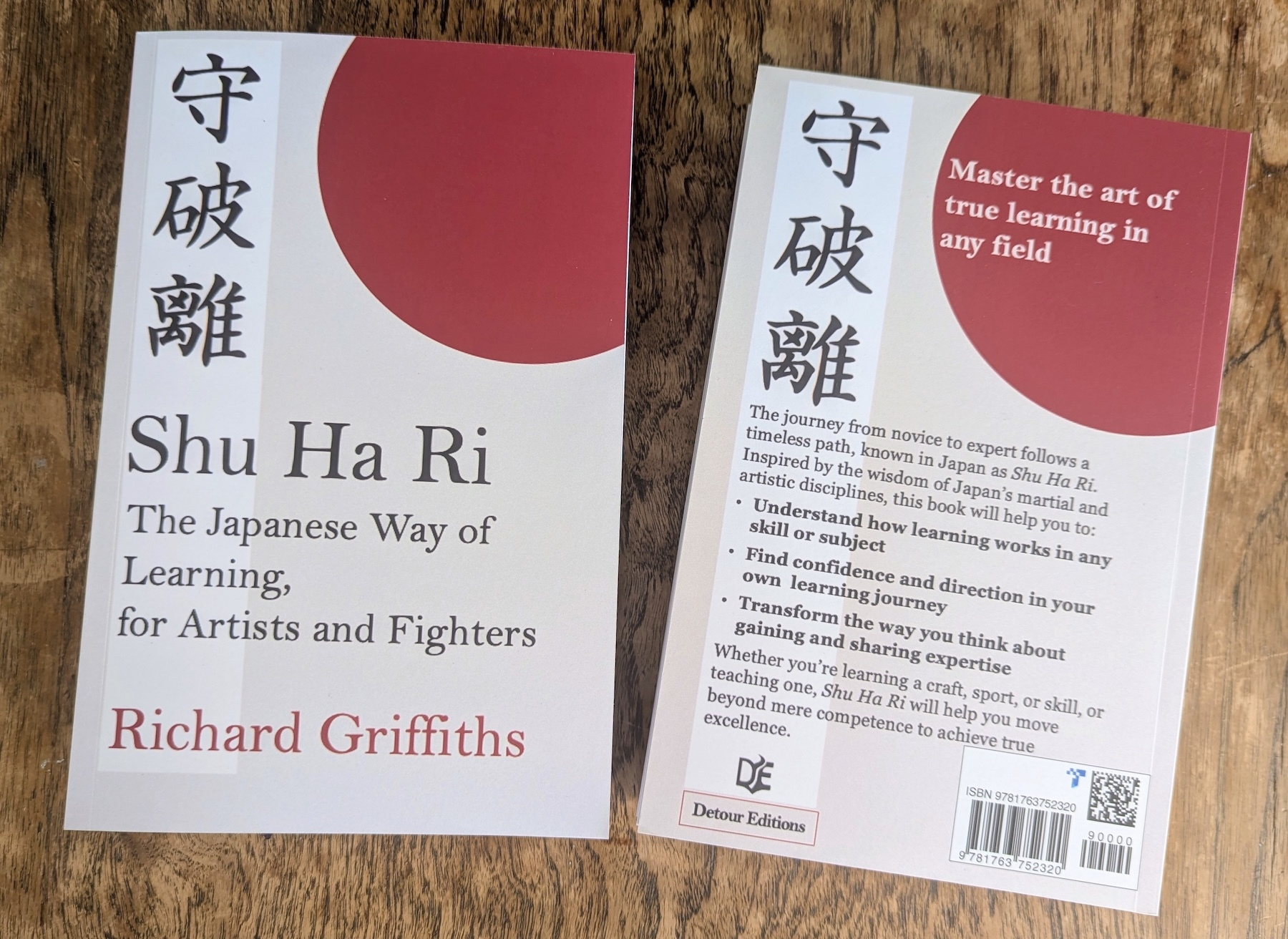

Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters is available now.

What's the true path of excellence?

Brad Stuhlberg’s book The Path of Excellence is a great read and it offers what the subtitle promises:

💬 A guide to true greatness and deep satisfaction in a chaotic world.

By now I’ve read many similar works and I’ve found there’s often something strangely missing. There’s usually heaps of good advice about acquiring expertise and wisdom, about learning and improving, and about following through; plenty too about commitment, discernment, patience and resilience. And these are all important factors if you want to attain excellence and some sort of mastery.

Well, OK. But there’s almost no mention of the need to find a teacher, coach or mentor — and to work constructively with them. And in this particular case I find it slightly weird. After all, the author is himself a performance coach, so why not at least mention the great benefits of working with a coach?

I see this as the most crucial aspect of learning, of trying to get better at something.

Learning is social: we learn best from other people, directly. That’s a key reason I was driven to write my own book, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning.

Reading all these American books on learning and improvement, I can’t help wondering if there isn’t a bias towards individualism at work here. Not that there’s anything wrong with individualism, but surely it isn’t the whole picture. Learning involves teachers. Is this claim so radical that it can’t be mentioned?

We don’t need to reinvent the wheel here. There’s a well-tested path and it’s clearly expressed in these three phases of the learning-teaching journey.

So sure, read another book about excellence. There are plenty to choose from.

But also, find the right teacher.

Now read:

What Billy Strings learned from his father

What Herbie Hancock learned from Miles Davis

The greatest experts are serial beginners

There’s a flaw in how we learn about expertise

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now.

And if you found this article interesting you might like to sign up to the Writing Slowly weekly email digest. You’ll receive all the week’s posts in that handy email format you know and love.

Beginners and intermediate learners fear ‘making mistakes’; experts seldom do. Not because experts don’t make mistakes: they do. It’s just that experts know what to do next.

Here’s Herbie Hancock telling what he learned from his mentor Miles Davis: Every mistake is an opportunity [openculture.com].

💬 I want to be just like him.

Imitation is one of the most powerful and underrated stages of learning. Billy Strings' story of learning guitar by watching his dad is the clearest example I’ve ever seen.

#Learning #Education #Music #ShuHaRi

"I want to be just like him"

“I want to be just like him.”

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of imitation as a crucial aspect of the learning journey. But it’s also hard to describe it in mere words.

In this deeply engaging YouTube interview with Rick Beato, virtuoso bluegrass guitarist Billy Strings recounts the way he learned his guitar skills early, at his father’s knee, by watching, by joining in. and by continually asking: “how does dad do it?”.

I’ve never seen a clearer example of the role of the imitation stage of learning, and exactly how it works.

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri. The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now.

Now read: Find the right teacher.

💬 “If it takes three years, find the right teacher.”

Sometimes the best way to find the right teacher is to start doing the work. Begin your learning journey visibly, and mentors may find you - like the barn builder who attracted an expert just by working in his driveway. Read more: writingslowly.com/2026/02/0…

How did you find your mentor?

#Learning #Mentorship #Writing #Creativity #Action #shuhari

Find the right teacher

There’s a Japanese saying that I included in my book:

If it takes three years, find the right teacher.

But sometimes, you just need to get started. Simon Sarris has a great story about this. He decided to build a barn by trial and error, with little previous barn-building experience. But because he was doing this near the road in front of his house, it attracted the attention of a regular passer-by who just happened to know, in detail, how to build barns.

“Mike would have never stopped by if I was not working conspicuously in my driveway, every day, under a pop-up tent. But I was, and he became interested in my progress, and it happens that he has been timber framing since the 90’s. Had I waited for such a teacher—for he has now taught me a good deal—I would have never found him. But I chose to start, and he was drawn to my adventure. Only by virtue of starting the work was the intersection of our lives possible.” - Start With Creation - by Simon Sarris

The moral? If it takes three years, find the right teacher. But if you start your learning journey with action, the right teacher might just find you.

So now here’s a question: Who was the right teacher for you, and how did you find them, or alternatively how did they find you?

(And yes, I have a story about a teacher who found me, but that’s a story for another time.)

Photo by Kazuhiro Yoshimura on Unsplash

Meanwhile, my book, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, is out now. Please check it out.

Discovery, aesthetics, and the art of self-publishing: my latest post explores Leonard Koren’s influence on my new book, Shu Ha Ri.

#WabiSabi #ShuHaRi #Japan #Aesthetics #WritingCommunity

Leonard Koren on Life as an Aesthetic Experience

I’ve never been much of a bathing person. Perhaps that’s due to unpleasantly lingering memories of luke warm water in freezing cold bathrooms in the UK when I was a child. The bath was fine enough, but getting out would be a real test. Even bathing, as an adult, in natural hot springs on Orcas Island in the US Pacific Northwest didn’t really do it for me. That was a little ‘rustic’, and not in a good way.

True, swimming here in Sydney where I live is fabulous, especially in the Summer, when the cool refreshment of the ocean waves is totally restorative. But bathing? Not so much. Until a few months ago, that is, when I visited Japan.

I hadn’t really understood the national Japanese obsession with bathing, but once I realised there are natural hot water sources all over the place in this volcanic archipelago, and how culturally central they are, and how refined the Japanese have made the whole bathing experience, I was completely hooked. In fact, returning to Australia, it feels strangely hard to live without it. Happily, a new spa and sauna has just opened up in our little neighbourhood, where my partner is already enjoying her season ticket. Come the Autumn, or even sooner, I’ll surely be joining her.

Which brings me to Leonard Koren, the august founder in the 1970s of ‘Gourmet Bathing’ magazine. He tells that story in a podcast interview. What particularly drew me to the interview though, was his account of how he came to write what he’s best known for — his cult book Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets and Philosophers. This book, published in 1994, has pretty much inspired not one but two cottage industries: one that centres on the concept of wabi-sabi, which now counts literally dozens of books exploring every possible angle of the term; and a second cottage industry that revolves around the exploration of Japanese concepts other than wabi-sabi, of which there are also now dozens. Who among us has not now heard of ikigai (finding your purpose), kaizen (continuous improvement), mono no aware (beauty in impermanance), shoshin (beginner’s mind) and so on and so forth?

Time Sensitive Podcast S11 E128 - 2 April 2025.Leonard Koren on Life as an Aesthetic Experience

I learned a few things from this podcast.

First, I learned that Leonard Koren had always intended to self-publish his book.

“When I made the first book," he said, “I thought it would be extremely niche… I realized that I would have to publish it myself.”

Second, I was happy to hear him fully owning the little secret of Wabi-Sabi, that there’s no such thing.

“Let me just be very clear: In Japanese there is no term wabi-sabi, OK? There’s an old word, ‘wabi’ and an old word ‘sabi’. If you look in the Japanese dictionary you won’t find wabi-sabi, period.”

Third, I was very taken with Koren’s description of his creative life:

”My life is essentially an aesthetic experience. Everything I know, everything I take in, every idea I have, comes to me through my senses. And then it’s processed.”

Well, Koren’s book is, quite clearly, the direct inspiration for my own, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters.

They’re both short, just 100 pages.

They’re both direct, covering one concept and one concept only.

They’re both Artist’s books, including photography (mine has 20 photographs of Japanese gardens, which I took myself).

They’re both originally self-published, to enable a singular, perhaps eccentric vision to find full expression.

They’re both the first book on a Japanese concept that no one in Japan, or anywhere else, has written yet, at least not a long-form treatment.

They’re both at the leading edge of an emerging trend.

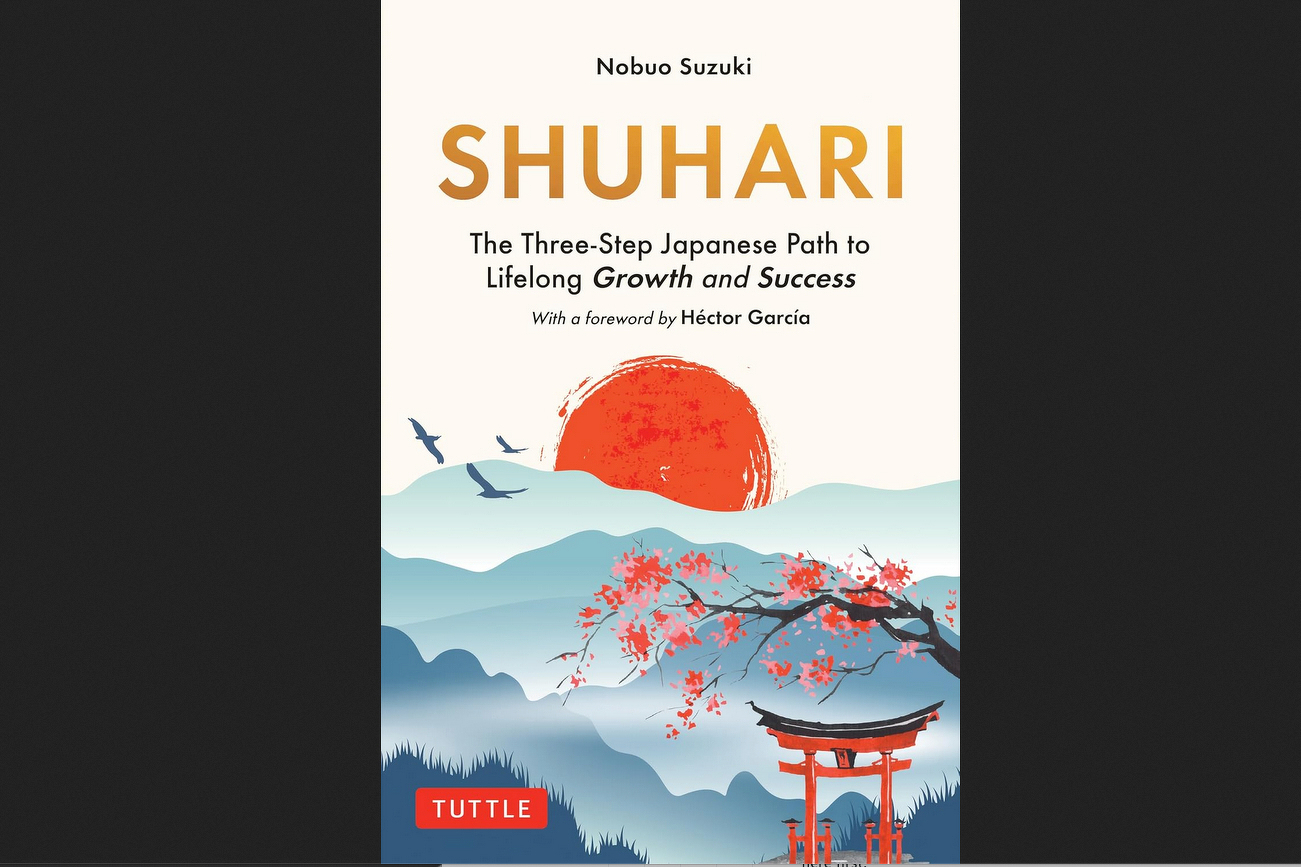

Wait! What? What emerging trend is this? Well, I waited 15 years for someone better qualified than me to write about the concept of Shu Ha Ri. No one did. At least, no one else wrote a clear, well-referenced, accessible introduction. Eventually I relented, wrote the book I wished already existed, and put it out there for readers to make their own judgement. But what do you know? Very shortly after I published my own introduction to the concept, another appeared, written by the partnership of Hector Garcia and Nobuo Suzuki. It’s in Spanish only for now, but the English version is published by Tuttle in August 2026, so perhaps soon there’ll be a Shu Ha Ri cottage industry. You heard it here first.

On my recent visit to Japan I walked past a gift shop in the small city of Matsumoto called ‘WabiXSabi’ (yes, in English), and it turns out there’s a whole chain of these stores across Japan. So maybe one day in the future someone will open a Shu Ha Ri shop, selling who-knows-what. Maybe it’ll be a footwear store. You heard that here first too.

But here’s word of warning to anyone thinking of trying this: Best not be selling anything fragile. Translated literally, Shu Ha Ri means ‘hold, break, leave’.

—

As you might have gathered, I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now.

And if you found this article interesting you might like to sign up to the Writing Slowly weekly email digest. You’ll receive all the week’s posts in that handy email format you know and love.

Every interface is an argument about how you should feel. - Phantom Obligation | Terry Godier

This is my view of writing and note-making apps, but we can change them, to feel how we want, not how someone else wants us to.

A channel of the Katsura River at Arashiyama, Kyoto.

Reviewing my photographs really makes me wish I was back in Japan.

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now.

#Japan #Kyoto #ShuHaRi #JapaneseCulture #JapaneseAesthetics #Photography

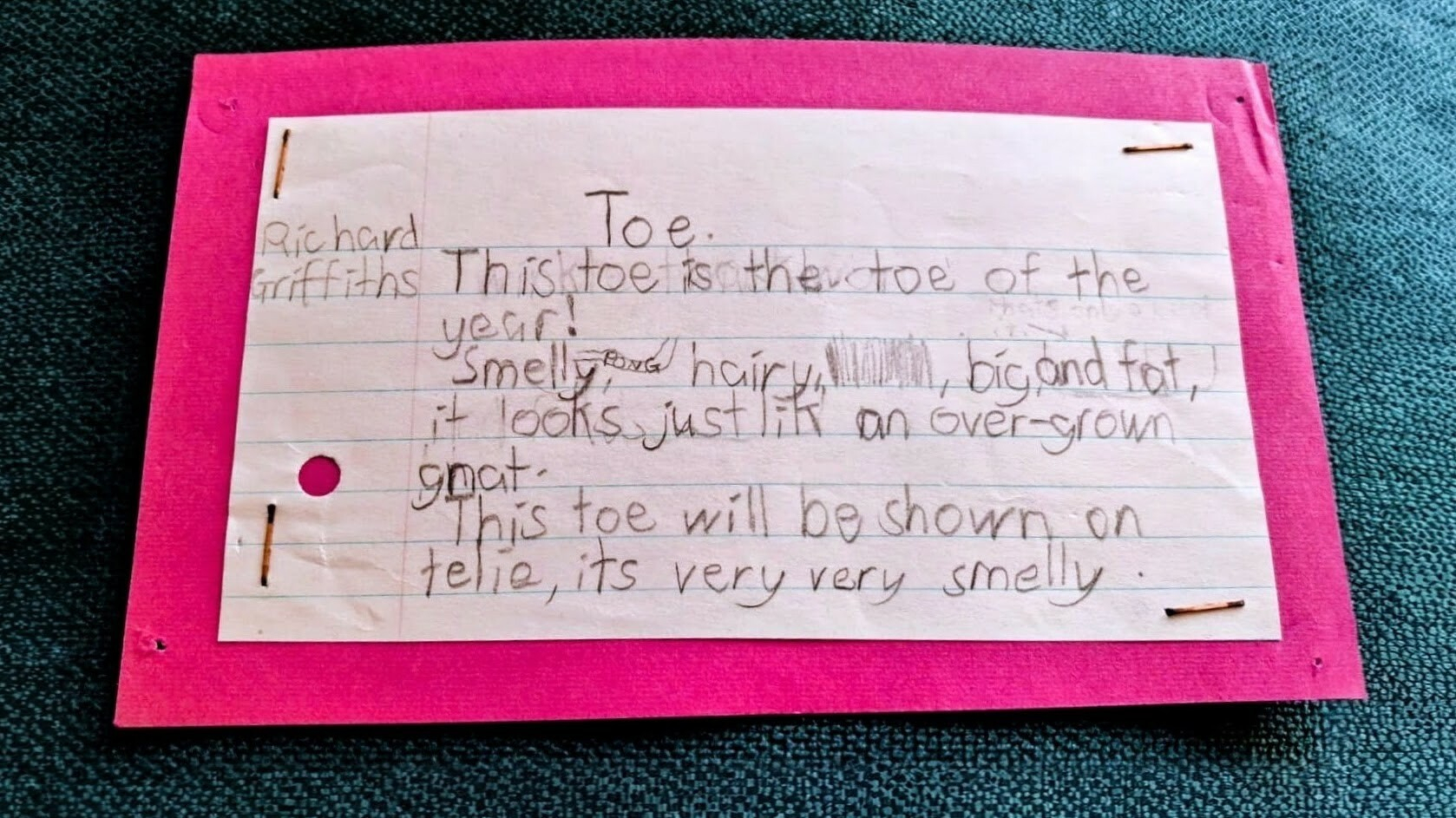

The Toe of the Year and the Curious Case of John Donne's Missing Commonplace Book

Last month, while my sister was moving house, she discovered a box of papers she’d never seen before. Inside was a collection of documents, decades old, that our parents must have gathered and kept from our childhood. There in a carefully wrapped pile was a sheaf of my sister’s old school reports. And next to them was a set of poems I must have written way back when I was a primary school student.

Perhaps you’ve had the experience of venturing into the attic or the basement and finding long-forgotten documents like these. But this chance rediscovery got me thinking about just how much has been lost to time.

Mostly we don’t bother archiving, and even when we do, there are later moments when we decide to spring-clean, rationalise, declutter, or tidy up.

These are all euphemisms for destroying the evidence.

Why your note-making tools don’t quite work the way you want them to - and what to do about it

Every so often I stumble upon a really clear articulation of a concept that makes sense of something I’ve been feeling but didn’t previously have a word for. I knew there was something there but I didn’t have the language to express it.

One of the most interesting articles I’ve come across recently is Artificial memory and orienting infinity by Kei Kreutler.

In this particular case the concept illuminated is the subtle, niggling tension between what I want to use my digital writing tools for and what they actually do. My writing tools, and possibly yours too, nearly do what I want, but not quite. What’s that about? Well, on reading this article, the tension became a whole lot clearer.

The Spiral of Mastery: Why the Greatest Experts Are Serial Beginners

The greatest experts aren’t afraid of starting again

Apparently, my tennis is rusty

Here in Australia the Christmas holidays take place in mid-summer, and my family spent a few days at a house with a tennis court. It was an amazing opportunity, for which we were hardly prepared. I hadn’t played in years. One family member had barely held a racquet before. But we all shared the same problem: our serves were terrible. The ball hit the net, or it veered wildly off court. The serve seemed like some monolithic, unreachable skill you either had or you didn’t.

The view from the court — that was amazing, but the tennis, to say the least, wasn’t flowing.

That was until someone suggested we break it down: grip, swing, ball toss, contact. We stopped trying to play and started drilling. Within a short while, the court was alive with movement and we were laughing instead of frowning with effort. Our natural talent hadn’t changed; it was just that our willingness to break the seemingly impossible into achievable parts made it somehow seem doable. And after a short while, it actually was doable. We were delivering serves that made it over the net, that you could also imagine returning.

This experience was a reminder that expertise is hardly ever about making a single massive effort to achieve something that seems impossible. You don’t get good at tennis all at once. Playing the game well is really a whole portfolio of tiny pieces of expertise you have to master one by one and piece together smoothly before you can reach actual proficiency. And even when you get there, that’s not the end. There’s always something, some element of your play, you can improve. Is mastery a destination to reach and then enjoy forever? No. It’s more like a spiral that requires us to return to the beginning again and again of a long series of micro-skills.

2025 marked 250 years since the birth of author Jane Austen. In 2026 she still has something important to teach us: “Feel the importance of every day, and every hour as it passes”.

—-

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri. The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now in paperback and ebook.

Looking back at 2025: a year of writing slowly but thinking with curiosity. 🖋️

From the note-making of Roland Barthes and Leibniz to reflections on AI and Japanese learning methods, here is a full archive of last year’s posts: Link

#Writing #Zettelkasten #PKM #AI #Learning #Blog #2025 #Shuhari

The posts of 2025

I’m much better at writing new stuff than consolidating the old, but it’s time to review what’s been posted here during 2025. Short posts excluded, it’s quite a lot, considering I’m Writing Slowly.

There’s also a list of the posts of 2024 and the posts of 2023 too.

And don’t forget to check out my book, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters.

To get the latest posts straight to your in-box, subscribe to the weekly Writing Slowly email newsletter.

Fact checking the good news

I expect 2026 to be a better year than 2025, not through some kind of magic but because millions of people like you and me are working hard to make it so. Since I posted a link to a round-up of the under-reported good news from 2025 someone said ‘some of this was definitely written with ai, so might be worth fact checking 😂’.

I was a bit disappointed, since I wanted the good news to be true, and since I have to admit this could easily make me susceptible to getting taken in by unreliable slop. Well, life’s too short to check all the facts, even if someone is wrong on the Internet (obligatory xkcd link), and that famous cartoon of the guy trying to fix it is actually an accurate drawing of me. But I thought I should at least do a quick audit. And what did this reveal?

The right kind of optimism in 2026

Happy New Year! May the next 12 months bring you peace and joy and blessing.

Here are a handful of hopeful articles to get your 2026 started on a positive note. I especially recommend the first one which I found deeply inspiring.

-

All the news the media missed in 2025 fixthenews.com (via Miraz Jordan.)

-

“The right kind of optimism is disciplined. It begins with the premise that action changes outcomes, then organizes institutions, incentives, and narratives to make that premise true.” mongabay.com.

-

The Sydney I know isn’t like what they’re showing on the news writingslowly.com.

“Bun without bu means authority withers, while bu without bun means the people remain in fear and distant.” —Fujiwara Shigenori, 1254.

Medieval Japan understood that true mastery requires balance. My latest article explores bunbu ichi and why “artists and fighters” belong together.

Read more: The unity of pen and sword: understanding bunbu ichi

#Bunbu #JapanesePhilosophy #Shuhari #SamuraiCulture #MedievalJapan #ArtAndWar #LifelongLearning #CulturalHistory #Mastery