A search for meaning in the palace of lost memories: Thoughts on Piranesi, a novel by Susanna Clarke

English author Susanna Clarke, published her second novel, Piranesi (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing), back in 2020, just as many of us were languishing in COVID lock-down.

And while, happily, the lock-down days are behind us, the impact of this intriguing, melancholy, and poignant tale has remained in my mind.

Piranesi, the protagonist, tells his own story, as though in a journal, though he’s not convinced he really is called Piranesi and as we shall see, he strongly distrusts his own writing. Piranesi, if that even is his name, inhabits a strange and eerily beautiful place which he calls the House. It’s an enormous, partly ruined building, devoid of human inhabitants but containing a few wild sea-birds and hundreds of huge statues which fill its endless empty, capriciously tide-swept halls. Piranesi has no memory or even concept of any other world, even though he occasionally receives a solitary visitor, whom he names The Other, a man he sees as a friend, but whom readers surely suspect may well be Piranesi’s jailer.

The House, of which Piranesi, sees himself as ‘the beloved child’ is a kind of accidentally or collectively created memory palace (Wikipedia), full of signifiers but lacking signification - perhaps like a whole culture. Piranesi has formed his own deeply reverential meaning out of this place, even as the memory of his real home, London, has faded into oblivion. He writes:

“Batter-Sea is not a word… [i]t has no referent. There is nothing in the World corresponding to that combination of sounds. (p.23)”

This novel operates at three levels at least:

First of all it’s a very timely meditation on abusive, narcissistic power and its antidote. Among the various characters there are two opposing world-views. There are those who see the world as merely to be used, of instrumental value only; and those who recognise an intrinsic value, and therefore cherish it. The author herself elaborated on this contrast in a newspaper interview:

“the divide is between people who see the world for what they can use it for, and the idea that the world is important because it is not human, it’s something we might be part of a community with, rather than just a resource. That is something that Piranesi grasps intuitively – that was very important, something I wanted to say.” (Interview with Susanna Clarke, 12 September 2020.)

At a second level, you could perhaps see the novel as a study of the loss of the Renaissance memory palace in European culture - “a careful exploration of the many different ways of passing on, storing, or communicating knowledge,” as one reviewer put it (Martin 2020). We have almost forgotten just how important the memory was in the days before the printing press, and we have certainly lost touch with the many ways this was a different world from our own.

Thirdly, the novel is an extended allegory of the author’s own years confined to home due to a debilitating experience of chronic fatigue syndrome (see The Guardian’s interview with the author, 12 September 2020) - and by extension a timely allegory of the universal COVID lockdown experience of 2020-21.

In the same interview, Susannah Clarke said:

“I was aware that I was a person cut off from the world, bound in one place by illness. Piranesi considers himself very free, but he’s cut off from the rest of humanity.” (Interview with Clarke 12 September 2020).

The Roman writer Cicero famously referred to a Greek legend which told of the prodigious memory of Simonides of Ceos (ca. 556-468 B.C.), who left a banqueting hall shortly before a fatal roof collapse, then was able to remember the identities and locations of all the dead banqueters.

He said:

Simonides “inferred that persons desiring to train this faculty must select places and form mental images of the things they wish to remember and store these images in the places so that the order of the places will preserve the order of things, and the images of the things will denote the things themselves, and we shall employ the places and images respectively as a wax-writing tablet and the letters written on it.” (Boorstin, 1984)

Quintillian (AD 35-92), another Roman writer, described his own method of the memory palace in similar terms:

“Think of a large building and walk through its numerous rooms remembering all the ornaments and furnishings in your imagination. Then give each idea to be remembered an image, and as you go through the building again, deposit each image in this order in your imagination. For example, if you mentally deposit a spear in the living room, an anchor in the dining room, you will later recall that you are first to speak of war, then of the navy, etc. The system still works!” (Boorstin, 1984)

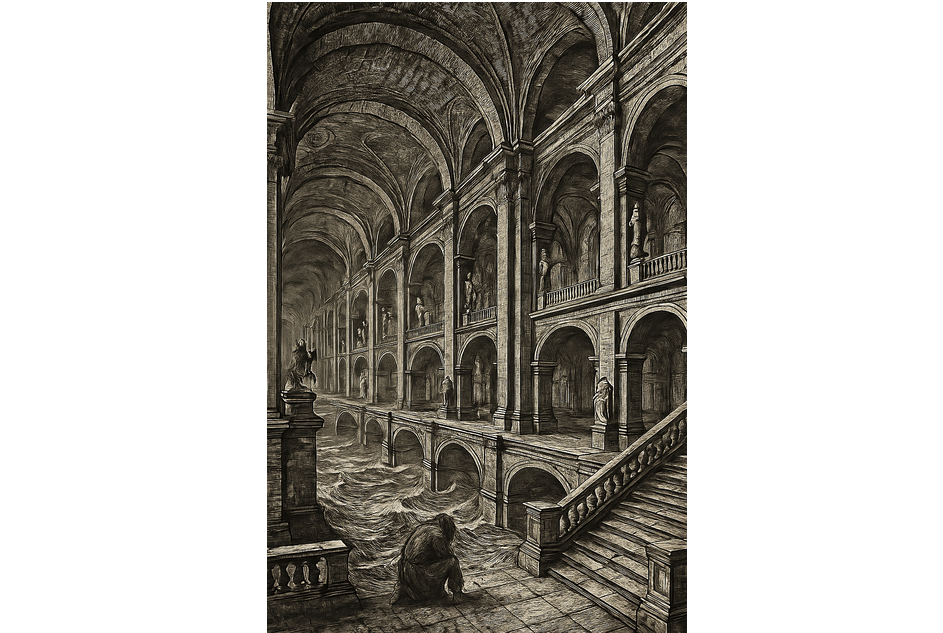

Image: The House, as ‘imagined’ by ChatGPT.

The last major iteration of the memory palace method, prior to the printing revolution, was that of Peter of Ravenna’s Phoenix, sive Artificiosa Memoria (‘The Phoenix, or Constructed Memory’, Venice, 1491). The author recommended imagining an empty church, then placing memory images in loci or places which were every five or six feet apart. In this way, the author claimed, he had placed 100,000 memory loci, even as a young man, and many more subsequently.

For Piranesi, the memory palace is a real, completely physical place. the House is real, but its referents are entirely obscure. If it meant something once, the meaning has been entirely lost. Piranesi loves the statue of the Faun ‘above all others’ he tells us, but has no idea why. It is left to the reader to recognise the pathos of the implied connection with C.S. Lewis’s fantasy world of Narnia, where a faun turned to stone is a key plot point. Perhaps this is a hint that the House is an external representation of Piranesi’s own memory. He has forgotten nearly everything, yet the loci of his missing memories remain.

In fact, for Piranesi, all memory systems other than the House itself are highly suspect. He distrusts the chalk writing he finds on the paving stones, and attempts to erase it. Later he realises his confidence in his own journals is entirely misplaced. He is his own ‘unreliable narrator’.

The problem of correspondence causes him anguish. He writes:

“I had a strong urge to fling the Journal away from me. The words on the page – (in my own writing!) – looked like words, but at the same time I knew they were meaningless. It was nonsense, gibberish! What meaning could words such as ‘Birmingham’ and ‘Perugia’ possibly have? None. There is nothing in the World that corresponds to them.”

This raises a wider question of how any kind of memory aid can really substitute for wisdom. In Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates tells of how the god Thamus, king of Egypt, rebuked Thoth, the god who invented writing:

“This discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners' souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality.” (quoted in Boorstin, 1984: 110)

While Piranesi can’t rely on his written words, and while he has no real idea what the statues in the halls are supposed to represent, he nevertheless inhabits a rich world of the imagination. Having forgotten the real world, Piranesi invents the referents for his secondary world. And by means of this imaginative faculty his fundamental humanity persists. Though Piranesi has forgotten his real existence as Matthew Rose Sorensen, and though all his writing is suspect, his faith in life remains and through it alone he retains his sanity:

“You are the Beloved Child of the House. Be comforted. And I am comforted.”

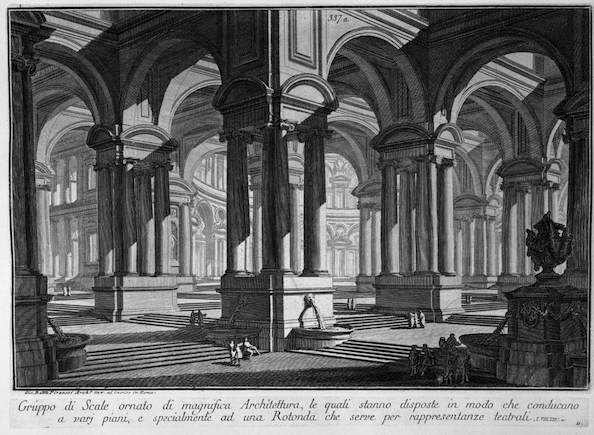

His consoling self-image is starkly at odds with the persona given him by the Other, the malevolent antagonist, who names him Piranesi, presumably alluding to the 17th Century Italian artist who etched a series of monumental imaginary prison scenes, Le Carceri d’Invenzione.

“I am Piranesi. But I knew that I did not really believe this. Piranesi is not my name. (I am almost certain that Piranesi is not my name.)”

As in ‘The House of Asterion’, a short story by Borges which the author thought she had forgotten, the reader, alongside the protagonist, must “penetrate to the identity of the prisoner and thus to the meaning of the story” (Redekop, 1980: 96).

On his eventual, eventful return to the everyday world, Matthew Rose Sorensen manages to maintain his connection to this intuitive sense of human dignity which the House enabled him to activate. Passing an elderly stranger in a park, he recognises him from one of the enigmatic statues in the House:

“He is shown as a king with a little model of a walled city in one hand while the other hand he raises in blessing. I wanted to seize hold of him and say to him: In another world you are a king, noble and good! I have seen it! But I hesitated a moment too long and he disappeared into the crowd.”

The novel concludes as it begins, with an affirmation that the beauty and kindness we seek in the world - any possible world - is exactly as much or little as we can find for ourselves.

The ending of the novel alludes to Plato’s parable of the cave. Having visited the upper world and observed at first hand the direct light of the sun, the former prisoner tries in vain to enlighten his fellow inmates who remain within the cave, misunderstanding the nature of the shadows they dimly observe. Which is the real world? Matthew Rose Sorensen sees paper lanterns hanging like fragile stars, “spheres of vivid orange that blew and trembled in the snow and the thin wind”. He concludes:

“The Beauty of the House is immeasurable; its Kindness infinite.”

On finishing the book I couldn’t help seeing the world I inhabit in a completely new light: viewed in this way the world is indeed a great memory palace created by our forbears, and around which we wander, only half cognizant of the significance of what we encounter. As the Italian author Roberto Callasso put it,

“We live in a warehouse of casts that have lost their moulds,” - Roberto Calasso, The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony (1988).

Our only option then is to try to create new meaning and hope from the broken, forgotten references that lie all around.

To those unable to recognise kindness and beauty where they are, perhaps every place and every possible world retains the nightmarish cast of the visions of the artist Piranesi’s labyrinthine prisons.

But to those who persistently pay attention with reverence, who continue to see and to name, despite everything, the world will respond by offering in return a difficult gift of freedom.

References

Boorstin, Daniel J. “The Lost Arts of Memory.” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-) 8, no. 2 (1984): 104-13. doi:10.2307/40256753. Adapted from Boorstin, Daniel Joseph., Luce, Clare Boothe. The discoverers. New York: Random House, 1983.

Susanna Clarke: ‘I was cut off from the world, bound in one place by illness’ The Guardian

Martin, Elyse, 2020. Beloved Child of the House: Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi and the Renaissance Memory Palace - Tor.com

Redekop, Ernest H. “Labyrinths in Time and Space.” Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 13, no. 3/4 (1980): 95-113.

Savas, Aysegul. “The Celestial Memory Palace.” The Paris Review, 7 Dec. 2018, www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/12/07/the-celestial-memory-palace/

Verardi, D. (2022). Memory in the Renaissance, Art of. In: Sgarbi, M. (eds) Encyclopedia of Renaissance Philosophy. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14169-5_445

Piranesi image (Public Domain), https://piranesi.dl.itc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/item/8012

Here’s another version of the ChatGPT image.

Thanks for reading this far. If you’ve enjoyed it, do consider subscribing to the weekly email digest.