books

- Plenty of clear and specific examples of notes of all sorts. People often ask ‘but what should a note look like?’ Here’s the answer, visually.

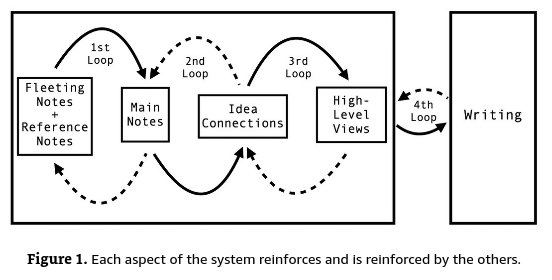

- Many helpful workflow diagrams. People also ask ‘how does the system operate as a whole?’ This book shows exactly how the Zettelkasten process works, and in what order.

- Clear references both to Niklas Luhmann’s process and to other relevant predecessors. If you want to refer back to the sources, there is a wealth of pointers here.

- At the end of each chapter, a checklist of specific activities to try, to implement the ideas just covered: what to do, what to remember and what to watch out for. If you’re wondering exactly what to do next with your notes, this book shows you (also, what not to do, especially in ch. 7).

- Helpful writing advice, which shows how to use your Zettelkasten to produce four different kinds of material: short-short items (i.e. social media posts), blog posts, articles and books.

- Overall, a clear, step-by-step, repeatable writing process to follow, from capturing your thoughts (ch. 1) right through to managing your writing workflow (ch. 9).

- What is the real work of serendipity?

- A library of good neighbours

- The Dewey Decimal System pigeonholes all knowledge, like cells in a prison

-

To clarify, I’m claiming, with Solms, that Freud’s pursuit was meta-psychological, not metaphysical. In contrast, I’m going further than Solms and reading Jung against himself here. Jung seems to have taken a strongly metaphysical approach (Mills 2019), whereas, I’m suggesting his programme may nevertheless be treated as a non-metaphysical but meta-psychological enquiry into the relationship between consciousness and human culture, not the brain. Mark Solms took part in a discussion on the differences between Freud and Jung. ↩︎

- Free-form note-making. In this mode, you start with no expectations and just make notes whenever something grabs you. This is great when you don’t yet know what you want to focus on. The risk is you try to read everything, only to discover it’s like drinking the ocean. Ars longa, vita brevis, so you’ll ultimately need to narrow down your field somehow.

- Directed note-making. In this mode, you already know, broadly, what interests you, for example, Richard Hamming’s 10-20 problems. So you make notes whenever something you read resonates with one of your predetermined interests. I used to think I was interested in everything, like Thomas Edison. But after writing notes on whatever took my fancy for a while, I observed that really, I kept revolving around a fairly limited set of concerns. So mostly these days I make directed notes, or else engage in the closely related purposeful note-making.

- Purposeful note-making. This mode is more focused still than directed note-making. Here you have a specific project in mind, such as a particular book or article you want to write, and so you make notes whenever your reading material chimes with what you want to write about. If there’s a risk to this kind of note-making, it’s that in your focused state, you’ll miss ideas that you might otherwise have found worth making notes about.

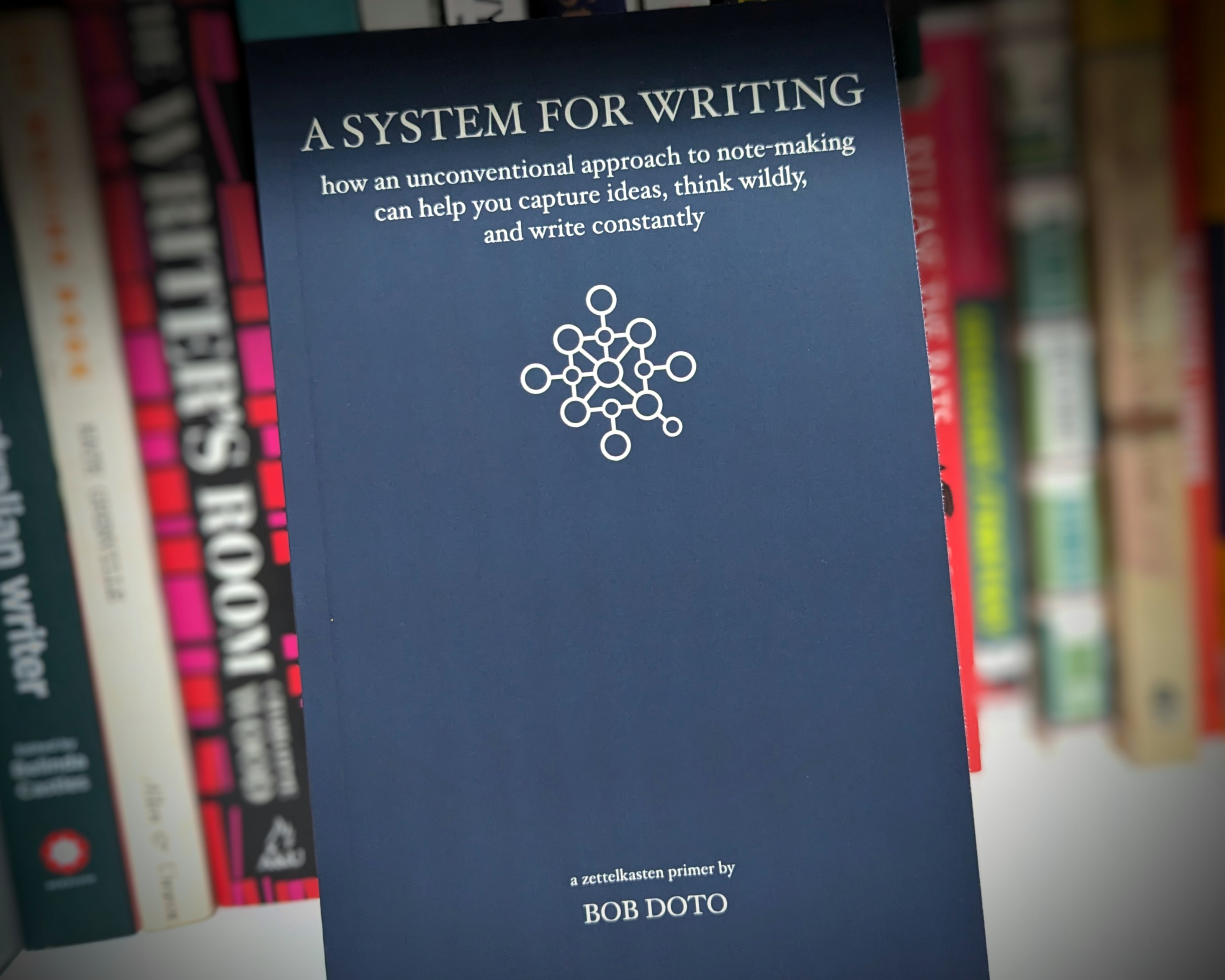

A System for Writing by Bob Doto

“The note you just took has yet to realize its potential.” - Bob Doto

Another ‘Zettelkasten primer’ won’t be needed for some time, since this one is direct, concise, thorough and strongly practical.

📚A System for Writing by Bob Doto is out!

If you’ve become confused or cynical watching those endless videos in which an influencer who discovered the Zettelkasten five minutes ago is suddenly the expert; or if you’ve read Sönke Ahrens' book, How to Take Smart Notes and thought “now I know why I should make notes but I still don’t really know how”, well here’s the antidote: the only Zettelkasten book you’ll ever need.

My paperback copy of A System for Writing arrived just in time for weekend reading. It’s a deliberately useful book, with a clear three-part structure. It gets to the point quickly and stays there: how to write notes, how to connect them and how to use this system to produce finished written work.

Things I especially appreciate in A System for Writing:

Will anyone be disappointed? Well, if you’re only looking for a manual on a particular piece of software, this book won’t satisfy you. It tells almost nothing about whatever the popular app-of-the-day is. You are not going to be told here whether Obsidian is better than Obshmidian. Software comes and goes, while the underlying principles of the Zettelkasten approach, as presented here, can be applied in many different contexts.

What about those who aren’t all that interested in actually publishing anything, who instead just want their notes to help them remember stuff, perhaps for tests? Well, although this book focuses without apology on writing, it will still be really useful for anyone making notes as a ‘second memory’ (Luhmann’s term) because by reading this (especially the first two parts) they’ll soon be making clearer, more concise and more accessible notes, whatever they intend to use them for.

And what of those who have absolutely no interest in obscure terms like ‘Zettelkasten’, who recoil from any kind of dubious productivity fetish, and just want to get things written? This is where the book excels and where it really comes good on the promise of its title. Yes, this is a system for writing. The author, who has himself written several books, shows from his direct experience how an effective note-making practice can lead to a more natural, unforced, effective and consistent writing practice. The Zettelkasten as presented here is an approach to note-making that will simply aid writing, without wasting time or effort.

This has certainly been my experience. Before I implemented my own Zettelkasten approach I was struggling both with organising my notes and with producing coherent writing. Since then, it’s been a different story. But until now there hasn’t been a Zettelkasten guidebook I’d wholeheartedly recommend to others. Now there certainly is.

So if you want to learn quickly how to capture your ideas effectively and write productively, stress-free, then get hold of A System for Writing right now.

More about Bob Doto.

Read about the illusion of integrated thought, which is cited in chapter 7 of the book.

My take on starting a Zettelkasten: How to make a Zettelkasten from your existing deep experience.

Why not let your reading be a smorgasbord of serendipity?

Yes indeed, why not let your reading be a smorgasbord of serendipity?

Here’s Anna Funder, author of Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life, on working at the University of Melbourne English Department library as a student:

“It sounds prehistoric now, but I sat at the front desk, typing out index cards for new acquisitions or requests from staff for books or journals — anything from the latest novel, to psychoanalysis, poetry or medieval studies. I read things that had nothing to do with my studies: a smorgasbord of serendipity. Despite my time there, I have never understood the Dewey decimal system: how can numbers tell you what a book is, to a decimal point?” - Every book you could want and many more

My take on this?

HEAJ:Mundaneum by Marc Wathieu is licensed under CC BY 2.0

🐙 Octopus intelligence is intriguing. Having read Ray Naylor’s The Mountain in the Sea 📚, I now want to try Other Minds: The Octopus and the Evolution of Intelligent Life by Peter Godfrey-Smith. I’d also like to read Children of Ruin by Adrian Tchaikovsky, which has a somewhat similar theme.

Finished reading: Ian Gentle: The Found Line, edited by David Roach 📚

I’ve posted about this interesting artist previously, because I loved The Gentle Project.

Finished reading: Always Will Be by Mykaela Saunders 📚

These short stories are set entirely in Australia’s Tweed region, but they range over a vast time-frame: from the more-or-less present to the far distant future. I loved the tough optimism. Always will be Aboriginal land - an ideal sci-fi theme.

Finished reading: Orbital by Samantha Harvey 📚

This reads curiously well alongside To be Taught, if Fortunate. Both describe spaceflight in mundane but compelling detail. Harvey is the stronger writer, but Chambers has the stronger story. Both are writing, for want of a better term, space pastoral.

Finished reading: To Be Taught, If Fortunate by Becky Chambers 📚My backlog of sci-fi reading is getting a little smaller.

Finished reading: A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers 📚I seem to be getting through the pile of sci-fi books that never shrinks but only grows.

At last, writing slowly is back in fashion!

Cal Newport, author of the forthcoming book, 📚Slow Productivity, has finally latched on to the premise of this website: you can get a lot done by writing slowly.

Speeding up in pursuit of fleeting moments of hyper-visibility is not necessarily the path to impact. It’s in slowing down that the real magic happens.

I didn’t even know they could drive.

See also:

Thinking nothing of walking long distances

How far is too far to walk?

Author Charlie Stross observed that British people in the early nineteenth century, prior to train travel, walked a lot further than people today think of as reasonable.

I’ve noticed a couple of literary examples of this seemingly extreme walking behaviour, both of which took place in North Wales.

Headlong Hall

In chapter 7 of Thomas Love Peacock’s satirical novel, 📚Headlong Hall (1816), a group of the main characters takes a morning walk to admire the land drainage scheme around the newly industrial village of Tremadoc, and they walk halfway across Eryri to do so, traversing two valleys and two mountain passes. The main object of their interest is The Cob, a land reclamation project that was later to become a railway causeway. Having seen it, and having taken some refreshment in the village, they walk straight back again.

Image: The Moelwyn range, viewed from the Cob. Wikipedia CC sharealike 2.0

Wild Wales

You’d think the invention of the railways would have put people off walking such long distances, but apparently not so much. In his travel account, 📚Wild Wales (1862), George Borrow walks from Chester 18 miles to Llangollen, then walks another 11 miles to Wrexham just to fetch a book. Interestingly, he was writing after the railways had arrived. He was happy to put his wife and children on the train - but still walk the journey himself.

Real life

I would have believed these feats of everyday walking were improbable, except for the fact that when I was a child, a man in our village, Mr Large, walked every day to and from Chester, a round trip of 26 miles. He didn’t need to do it. He was in his eighties and well retired, and he could just have walked two miles to the bus stop. But apparently you don’t break the habits of a lifetime. Everyone in the village must have offered him a lift at one time or another, but he’d made it known that he preferred to walk. So having observed Mr Large regularly tramping the back lanes with determination, I already knew a long utility walk is more than possible.

These days, people rarely get out of their cars, convinced as they are that progress has been made. Walking is a problem, it seems, not a solution. And yet, on holiday, some people do long walks or even very long walks. For fun.

Oh brave new world that has such people in it!

Can we understand consciousness yet?

Professor Mark Solms, Director of Neuropsychology at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, revives the Freudian view that consciousness is driven by basic physiological motivations such as hunger. Crucially, consciousness is not an evolutionary accident but is motivated. Motivated consciousnesses, he claims, provides evolutionary benefits.

Mark Solms. 2021. The Hidden Spring. A Journey to the Source of Consciousness. London: Profile Books. ISBN: 9781788167628

He claims the physical seat of consciousness is in the brain stem, not the cortex. He further claims that artificial consciousness is not in principle a hard philosophical problem. The artificial construction of a conscious being, that mirrors in some way the biophysical human consciousness, would ‘simply’ require an artificial brain stem of some sort.

I have been wondering what it would be like to have injuries so radical as to destroy the physiological consciousnesses, if such a thing exists, while retaining the ability to speak coherently and to respond to speech. Perhaps a person in this condition would be like the old computer simulation, Eliza, which emulated conversation in a rudimentary fashion by responding with open comments and questions, such as “tell me more”, and by mirroring its human conversation partner. The illusion of consciousness was easily dispelled. The words were there but there was no conscious subject directing them. However, since then language processing has become significantly more advanced and machine learning has progressed the ability of bots without consciousness to have what appears to be a conscious conversation. Yet still there’s a suspicion that there’s something missing.

One area of great advance is the ability of machine learning to take advantage of huge bodies of data, for example, a significant proportion of the text of all the books ever published, or literally billions of phone text messages, or billions of voice phone conversations. It’s possible to program with some sophistication interactions based on precedent: what is the usual kind of response to this kind of question? Unlike Eliza, the repertoire of speech doesn’t need to be predetermined and limited, it can be done on the fly in an open ended manner using AI techniques. But there’s still no experiencer there, and we (just about) recognise this lack. Even if we didn’t know it, and bots already passed among us incognito, they might still lack ‘consciousness’.

So, at what point does the artificial speaker become conscious? If the strictly biophysical view of consciousness is correct, the answer is never.

A chat bot will never “wake up” and recognise itself, because it lacks a brain stem, even an artificial one. Even if to an observer the chat-bot appears fully conscious, at least functionally, this will always be an illusion, because there is no felt experience of what it is like to be a chat bot, phenomenologically.

From the perspective of neo-Freudian neuropsychology, it is easy to see why Freud grew exasperated with Carl Jung. Quite apart from the notorious personality clashes, it seems Jung departed fundamentally from Freud’s desire to relate psychological processes to their physical determinants. For example, what possible biophysical process would be represented by the phrase “collective unconscious” (see Mills 2019)?

For Freud, the consciousness was strongly influenced by the unconscious, which was his term for the more basic drives of the body. For example, the Id was his term for the basic desire for food, for sex, to void, etcetera. This was unconscious because the conscious receives this information as demands from a location beyond itself, which it finds itself mediating.

He saw terms such as the Id, the Ego and the Superego as meta-psychological. He recognised what was not at the time known about the brain, such as the question of where exactly the Id is located, but he denied it was a metaphysical term. In other words, he claimed that the Id was located, physically, somewhere, yet to be discovered. His difficulty was he fully understood that his generation lacked the tools to discover where.

Note that meta-psychology is explicitly not metaphysical. Freud had no more interest in the metaphysical than other scientists of his time, or perhaps ours have done. His terminology was a stopgap measure meant to last only until the tools caught up with the programme.

The programme was always: to describe how the brain derives the mind.

Jung’s approach made a mockery of these aspirations. Surely no programme would ever locate the seat of the collective unconscious?

But perhaps this is a misunderstanding of the conflict between Freud and Jung. What if the distinction is actually between two conflicting views of the location of consciousness? For Freud, and for contemporary psychology, if consciousness is not located physically, either in the brain somewhere or in an artificial analogue of the brain, where could it possibly be located? Merely to ask the question seems to invite a chaos of metaphysical speculation. The proposals will be unfalsifiable, and therefore not scientific - “not even wrong”.

However, just as Mark Solms has proposed a re-evaluation of Freud’s project along biophysical lines, potentially acceptable in principle to materialists and empiricists (i.e. the entire psychological mainstream), perhaps it is possible for a re-evaluation of Jung’s programme along similar lines, but in a radically different direction.

If the brain is not the seat of the conscious, what possibly could be? This question reminds me of the argument in evolutionary biology about game theory. Prior to the development of game theory it was impossible to imagine what kind of mechanism could possibly direct evolution other than the biological. It seemed a non-question. Then along came John Maynard Smith’s application of game theory to ritualised conflict behaviour and altruism, and proved decisively that non-biological factors decisively shape evolutionary change.

What if Jung’s terms could be viewed as being just as meta-psychological as Freud’s, but with an entirely different substantive basis? Lacking the practical tools to investigate, Jung resorted to terms that mediated between the contemporary understanding of the way language (and culture more generally), not biology, constructs consciousness.

What else is “the collective unconscious”, if not an evocative meta-psychological term for the corpus of machine learning?

Perhaps consciousness is just a facility with a representative subset of the whole culture.

I’m wary of over-using the term ‘emergence’. I don’t want to speak of consciousness as an emergent property, not least because every sentence with that word in it still seems to make sense if you substitute the word ‘mysterious’. In other words, ‘emergence’ seems to do no explanatory work at all. It just defers the actual, eventual explanation. Even the so-called technical definitions seem to perform this trick and no more.

However, it’s still worth asking the question, when does consciousness arise? As far as I can understand Mark Solms, the answer is, when there’s a part of the brain that constructs it biophysically, and therefore, perhaps disturbingly, when there’s an analogue machine that reconstructs it, for example, computationally.

My scepticism responds: knowing exactly where consciousness happens is a great advance for sure, but this is still a long way from knowing how consciousness starts. The fundamental origin of consciousness still seems to be shrouded in mystery. And at this point you might as well say it’s an ‘emergent’ property of the brain stem.

For Solms, feeling is the key. Consciousness is the theatre in which discernment between conflicting drives plays out. Let’s say I’m really thirsty but also really tired. I could fetch myself a drink but I’m just too weary to do so. Instead, I fall asleep. What part of me is making these trade-offs between competing biological drives? On Solms’s account, this decision-making is precisely what conscousness is for. If all behaviour was automatic, there would be nothing for consciousness to do.

As Solms claims in a recent paper (2022) on animal sentience, there is a minimal key (functional) criterion for consciousness:

The organism must have the capacity to satisfy its multiple needs – by trial and error – in unpredicted situations (e.g., novel situations), using voluntary behaviour.

The phenomenological feeling of conscioussness, then, might be no more than the process of evaluating the success of such voluntary decision-making in the absence of a pre-determined ‘correct’ choice. He says:

It is difficult to imagine how such behaviour can occur except through subjective modulation of its success or failure within a phenotypic preference distribution. This modulation, it seems to me, just is feeling (from the viewpoint of the organism).

Then there’s the linguistic-cultural approach that I’ve fancifully been calling a kind of neo-Jungianism 1. When does consciousness emerge? The answer seems to be that the culture is conscious, and sufficient participation in its networks is enough for it to arise. If this sounds extremely unlikely (and it certainly does to me), consider two factors that might minimise the task in hand - first that most language is merely transactional and second that most awareness is not conscious.

As in the case of chat bots, much of what passes for consciousness is actually merely the use of transactional language, which is why Eliza was such a hit when it first came out. This transactional language could in principle be dispensed with, and bots could just talk to other bots. What then would be left? What part of linguistic interaction actually requires consciousness? Perhaps the answer is not much. Furthermore, even complex human consciousness spends much of the time on standby. Not only are we asleep for a third of our lives, but even when we’re awake we are often not fully conscious. So much of our lives is effectively automatic or semi automatic.

When we ask what is it like… the answer is often that it’s not really like anything.

The classic example is the feeling of having driven home from work, fully awake, presumably, of the traffic conditions, but with no recollection of the journey. It’s not merely that there’s no memory of the trip, it’s that, slightly disturbingly, there was no real felt experience of the trip to have a memory about. This is disturbing because of the suspicion that perhaps a lot of life is actually no more strongly experienced than this.

These observations don’t remove the task of explaining consciousness, but they do point to the possibility that the eventual explanation may be less dramatic than it might at first appear.

For the linguistic (neo-Jungian??) approach to consciousness the task then is to devise computational interactions sufficiently advanced as to cause integrated pattern recognition and manipulation to become genuinely self aware.

A great advantage of this approach is that it doesn’t matter at all if consciousness never results. Machine learning will still advance fruitfully.

For the biophysical (neo-Freudian) approach, the task is to describe the physical workings of self awareness in the brain stem so as to make its emulation possible in another, presumably computational, medium.

A great advantage of this approach is that even if the physical basis of consciousness is not demystified, neuropsychology will still understand more about the brain stem.

As far as I can see, both of these tasks are monumental, and one or both might fail. However, the way I’ve described them they seem to be converging on the idea that consciousness can in principle be abstracted from the mammalian brain and placed somewhere else, whether physical or virtual, whether derived from the individual brain, analogue or digital, or collective corpus, physical or virtual.

I noticed in the latter part of Professor Solms’s book a kind of impatience for a near future in which the mysteries of consciousness are resolved. I wonder if this is in part the restlessness of an older man who would rather not accept that he might die before seeing at least some of the major scientific breakthroughs that his life’s work has prepared for. Will we work out the nature of consciousness in the next few years, or will this puzzle remain, for a future generation to solve? I certainly hope we have answers soon!.

References:

Mills, J. (2019). The myth of the collective unconscious. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 55(1), 40-53.

Solms, Mark (2022) Truly minimal criteria for animal sentience. Animal Sentience 32(2) DOI: 10.51291/2377-7478.1711

Jules Verne could have told us AI is not a real person

Three worthwhile modes of note-making (and one not-so-worthwhile)

I finished reading Alex Kerr’s Finding the Heart Sutra on New Year’s Eve, so it just scraped into my reading for 2023. And while reading I made notes by hand, as I’ve done before. Although there aren’t very many notes (just eleven, plus a literature note that acts as a mini-index), they’re high quality, since I found the book very interesting.

I don’t mean I’ve written objectively ‘good’ notes. Rather, I mean the notes are high quality for my purposes. Everyone who reads with a pen in hand is an active reader, so the notes one person makes will be different - perhaps completely different- from the notes another person makes. In any case, no two readers read a book the same way.

Reflecting on this it seems to me there are at least three fruitful ways, or modes, of making notes while reading, as follows: Free-form, directed, and purposeful note-making.

Each of these note-making modes has its place, but in this particular case I was reading Finding the Heart Sutra with a very specific project in mind. So the notes I made were also quite specific. I imagine that someone else would be surprised by the notes I made, since they don’t really reflect the contents of the book. For instance, my notes are definitely not a summary of the book’s contents. Nor do they even follow the main contours of the book’s themes. Instead, I was making connections while reading with the main concerns of my own project. Each of my notes stands in its own right and could potentially be used in a variety of different contexts, but collectively, they make sense in relation to my own preoccupations. They fit into my own Zettelkasten, and no one else’s.

“Most great people also have 10 to 20 problems they regard as basic and of great importance, and which they currently do not know how to solve. They keep them in their mind, hoping to get a clue as to how to solve them. When a clue does appear they generally drop other things and get to work immediately on the important problem. Therefore they tend to come in first, and the others who come in later are soon forgotten. I must warn you, however, that the importance of the result is not the measure of the importance of the problem. The three problems in physics—anti-gravity, teleportation, and time travel—are seldom worked on because we have so few clues as to how to start. A problem is important partly because there is a possible attack on it and not just because of its inherent importance.”

If you want to know more about how to read a book, you could do worse than read How to Read a Book, by Mortimer Adler. It’s not the last word on the subject, but it’s a good starting point.

And it’s a warning against a fourth mode of note-making that I don’t advise: encyclopedic note-making. This is where you read a book and try to write a summary that will work for everyone. First, it’s hard work, and secondly, it’s probably already been done. If you open the link above you’ll see that the Wikipedia entry for How to Read a Book already includes a summary of the book’s contents. There are circumstances where the careful and complete summary is worthwhile, but I suggest you only start this task with the end - your own end - in mind.

If you have thoughts about making notes while reading, I’d be very interested to hear about it.

See also:

A note on the craft of note-writing

Learning to make notes like Leonardo

The real story of Napoleon?

If you’re thinking of viewing Ridley Scott’s movie version of Napoleon 🍿, or if you’ve already seen it, I’d recommend also reading The Black Count: Glory, Revolution, Betrayal, and the Real Count of Monte Cristo by Tom Reiss. 📚

This Pulitzer prizewinning biography puts Napoleon’s life and times in historical context and it’s an amazing story. The ‘black count’ of the title was Alexandre Dumas, father of the famous author of The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers. He rose from obscurity to became Napoleon’s commander of cavalry during the Egyptian campaign.

But quite unlike Napoleon, he seems to have been motivated by something rather more than personal glory. He actually believed in the ideals of the Revolution, not least the implementation of Liberté.

As an aside, the book provides a huge number of fascinating factoids, such as why dolomite (the mineral as well as the mountain range) is named dolomite.

Publish first, write later

“Literature is perhaps nothing more complicated and glorious than the act of writing and publishing, and publishing again and again."

- Marcelo Ballvé, on the curious writing career of César Aira

César Aira on the constant flight forward

Argentinian author César Aira’s writing process is more about action than reflection. In a moment I’m going to share with you an extract from The Literary Alchemy of César Aira, an essay by Marcelo Ballvé, originally published in The Quarterly Conversation in 2008.

But before coming to the extract, I’ll just comment on David Kurnick’s claim in Public Books that Aira’s work is primarily about process:

“It is not in the least original to begin talking about César Aira’s work by recounting the technique that produces it. But it can’t be helped: Aira has made a discussion of his practice obligatory. To read him is less to evaluate a freestanding book, or a series of them, than to encounter one of the most extraordinary ongoing projects in contemporary literature.”

True, I’m not being at all original here, just cutting and pasting. Still…

Aira’s own Aleph

It’s as though through his writing Aira has found the basement in Buenos Aires that contains the entire universe in condensed form, the basement that features in Borges’s 1945 story “The Aleph”.

And having found that fabled basement, it’s as though Aira has taken on the persona of Carlos Argentino Daneri, the character in Borges' story whose life’s obsessive goal is to write a poetic epic describing each and every location on Earth in perfect detail.

But instead of taking the find seriously, Aira parodies it. Everything is here: and what do you know? None of it makes sense! Or, perhaps instead of parodying “The Aleph”, he takes it completely seriously: Why not write about it, about all of it? What then? In an interview in 2017 for the New Yorker, Aira said: “I am thinking now that maybe . . . maybe all my work is a footnote to Borges.”

Of course I’m not just cutting and pasting. I’m writing too. Aira also inspires my own writing process. His example inspires me to choose my own race - and finish it.

One of my role models is the Argentinian author César Aira. He’s written a very large number of novels and novellas (at least 80 - around two to five per year since 1993), published by a variety of presses. That’s a lot of races and a lot of finish lines crossed.

Now here’s Marcelo Ballvé on Aira’s unique writing process.

According to Aira, he never edits his own work, nor does he plan ahead of time how his novels will end, or even what twists and turns they will take in the next writing session. He is loyal to his idea that making art is above all a question of procedure. The artist’s role, Aira says, is to invent procedures (experiments) by which art can be made. Whether he executes these or not is secondary; Aira’s business is the plan, not necessarily the result. Why is procedure all-important? Because it is relevant beyond the individual creator. Anyone can use it.

Aira’s procedure, which he has elucidated in essays and interviews, is what he calls el continuo, or la huida hacia adelante. These concepts might be translated into English as “the continuum,” and a “constant flight forward.” Editing is an abhorrent idea in the context of Aira’s continuum. To edit oneself would be to retrace one’s steps, go backwards, when the idea is to always move forward. To judge yesterday’s writing session, to censor a lapse into the absurd or the irrational, to revive a character your work-in-progress sent tumbling over a cliff—all of these actions go against Aira’s procedure. Instead, the system prioritizes an ethic of creative self-affirmation and, I would say, optimism. To labor to justify previous work with more strange creations that in turn establish the need for ever more artistic high-wire acts in the future—this is the continuum, the high-wire act the artist must perform when he refuses to submit to any rule that is not his autonomously chosen procedure. It is an act performed with deep abysses yawning to each side of him—conformity, market pressures, conventionality, self-repression of all kinds . . . In other words, Aira’s literary career, embodied in each of his 63 novels, is a reckless pursuit of artistic freedom.

Aira says that when he sits down to write his daily page or two, he writes pretty much whatever comes into his head, with no strictures except that of continuing the previous day’s work. (The spontaneous feel of his stories would seem to back up this claim, but I’ve always asked, can anyone write as well as Aira does while simply letting the pen ramble?)

True, his books are very short. Aira says in interviews that he’s often tried to make his novels longer, but they seem to come to a natural rest at around the 100-page mark. Technically, much of what Aira has written would have to be classified in the novella category, but it’s hard to classify Aira’s work within any genre, be it story, novel, or novella. In my mind, Aira’s creations are something different altogether. They are stories, pure and simple, which Aira has managed to ennoble by seeing them into publication in the form of a single book. What he has done is put stories into circulation as objects, which is a defiant feat when seen in the context of a global literary market that demands hefty, sprawling, “big” novels.

The key to Aira’s curious career, I think, is to be found in his conception of literature as something with more affinities to the realm of action than the inner world of reflection. Literature is perhaps nothing more complicated and glorious than the act of writing and publishing, and publishing again and again. Editing is dispensable, so is the search for the “right” publisher. (Aira publishes seemingly with whomever shows any interest in his manuscripts; at least a dozen publishers, most of them small independents, in Argentina alone.) The idea seems to be: publish first and ask questions later…In fact Aira’s mentor, the deceased Argentine poet and novelist Osvaldo Lamborghini had a saying: “Publish first, write later.”

Extracted from The Literary Alchemy of César Aira, by Marcelo Ballvé. The Quarterly Conversation

César Aira’s main publisher in English is New Directions. They’ve published about 21 of Aira’s works in translation, while And Other Stories has published another half-dozen.

Now read: Choose your own race

Finished reading: The Real Work by Adam Gopnik 📚A great section on the art of magic and the significance of S.W. Erdnase’s book, The Expert at the Card Table. Apparently, when magicians want to learn a new trick from the top expert, they ask, “Who has the real work?” It’s a useful question, and not just for magic tricks. Gopnik, long a masterly writer, tries his hand at a series of *new * skills, including driving, making bread, dancing, and alarmingly, urinating in public. That last one does make sense, but you have to read the book to find out why. I also found out that when a magician catches a bullet, it’s real. Sometimes, the trick is that you have to catch the bullet.

I’ve written more about this book: What is the real work of serendipity?

It strikes me that one significant feature of mastery is to be able to spot a lucky opportunity and then make something of it. The expert can’t help but see it. Everyone else would miss this chance moment, or else be unable to execute the essential implementation.

How many books are you reading?

On Mastodon, Evan Prodromou asked “How many books are you reading?” and I was slightly shocked by the results.

Only 5% of 569 people said they were reading six or more books. I thought I was quite normal, but it turns out I’m not. Currently I’m officially reading seven books, but that doesn’t include the four books I’ve finished recently that never made it onto the ‘currently reading’ list. Somehow, having a list of books I’m reading makes me want to read different books. I get through about 35-40 a year, which isn’t a terribly low number, so even though I get stuck on some books, seeming to take months to finish them, I still manage to read quite a few.

Perhaps I’m just starting into my to-be-read pile too early. Maybe I could resist this.

Actually I don’t think I’m at all normal, but everything I do feels normal. And who am I kidding? I can’t resist starting new books. Can you?

Finished reading: Show Your Work! by Austin Kleon. 📚

Loving Austin Kleon’s blog, I ordered his trilogy from my local bookstore. Also finished Keep Going. Now just have Steal Like an Artist to read. Yes, I’m reading them in the wrong order LOL.

#reading

What is the real work of Serendipity?

Currently reading: The Real Work by Adam Gopnik 📚

The Real Work is what magicians call ‘the accumulated craft that makes for a great trick’, and the enigmatic S.W.Erdnase was a master. Adam Gopnik’s book on the nature of mastery devotes a whole chapter to him, so I was amused to find him also mentioned on the new series of Good Omens. This is a great example of the chance happening that people often confuse with serendipity. But as Mark De Rond claims serendipity isn’t luck alone. It’s really the relationship between good fortune and the prepared mind:

“serendipity results from identifying ‘matching pairs’ of events that are put to practical or strategic use.”

On this account it’s not luck or chance that matters, but the human agency that does something with it. From two chance encounters with S.W. Erdnase that seemed to match, I’ve constructed this short post. In his 2014 article, ‘The structure of serendipity’, De Rond identifies some examples of much more significant serendipity in the field of scientific innovation.

It strikes me that one significant feature of mastery is to be able to spot a lucky opportunity and then make something of it. The expert can’t help but see it. Everyone else would miss this chance moment, or else be unable to execute the essential implementation.

Reference: De Rond, Mark. “The structure of serendipity.” Culture and Organization 20, no. 5 (2014): 342-358. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2014.967451

Currently reading: Milkman by Anna Burns. 📚 By turns hilarious and harrowing. It’s not at all how I imagined it, which was mainly harrowing. Sure, the eponymous ‘Milkman’ is deeply sinister (and the narrative has only just got going), but the narrator’s voice is fantastically funny and engaging.

I have elephants

A chapter of Sarah Bakewell’s book Humanly Possible considers the life and times of Renaissance scholar Petrarch. Petrarch, she says, wrote a book called Remedies for Fortune Fair and Foul (1360), which is a dialogue between three embodied figures: Reason, Sorrow and Joy. Reason’s job here is both to cheer up Sorrow and to settle down Joy.

At one point, Joy says, “I have elephants.”

Reason replies, “May I ask for what purpose?”

Bakewell’s comment: “No answer is recorded.”

(Bakewell, 2023: 52)

💬 📚