Jules Verne could have told us AI is not a real person

A castle of mysterious voices

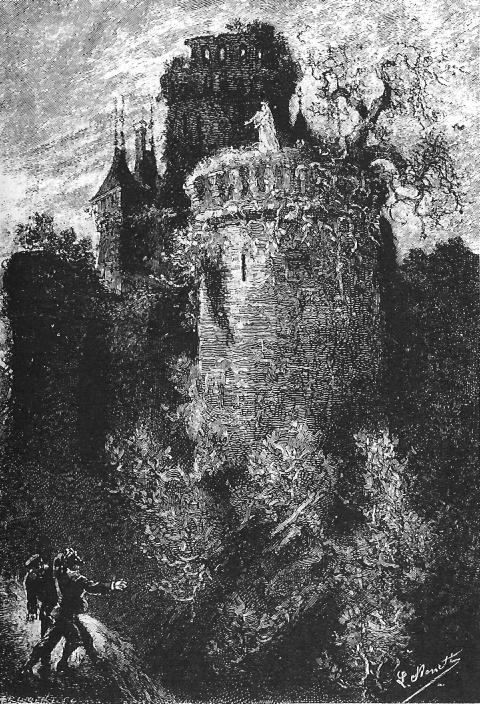

In one of French writer Jules Verne’s many sensational novels, The Carpathian Castle, the hero, Count Franz de Telek, investigates a creepy Transylvanian castle. The castle is rumoured to be haunted by the ghost of his former love, the Italian opera diva, La Stilla. Rumours of sightings suggest that sensationally, La Stilla has come back to life!

“If La Stilla were dead, how came it that Franz could hear her voice in the saloon of the inn, see her on the bastion, and listen to her song when he was in the crypt? And how could he have found her alive in the donjon?”

After much gothic prose, it turns out that [Spoiler:] the supposed ghost is nothing more than a photographic wall projection and a ‘high quality’ phonograph recording of the singer’s voice. The re-staging of La Stilla’s performance has been set up for the castle’s owner, Baron Rodolphe de Gortz, who had also loved La Stilla when she was alive.

In 1892 when the novel was published, these were still new inventions, so readers would have found the happenings at the castle truly mysterious, and the ending not at all corny. Verne probably first experienced a demonstration of an Edison phonograph 14 years previously, at the 1878 Paris World’s Fair, and it appeared shortly after in his 1879 novel, The Tribulations of a Chinaman.

In fact, the story is more science fiction than Gothic horror (‘This story is not fantastic, it is merely romantic", states the author at the start). New technology presents the convincing appearance of life, which fools all observers - until the trick is finally revealed. And even then, there are some who prefer to believe in the supernatural explanation, despite the evidence.

La Stilla Syndrome

You can probably see where this is going.

With the rise of large language models (LLMs), we are once more suffering from La Stilla Syndrome. That’s my Jules Verne-inspired name for the condition in which we keep allowing our technology to fool us into thinking it has finally come alive.

But it’s not the technology itself that’s tricking us, any more than La Stilla the Italian diva had any hand in her audiovisual reconstruction. She was well and truly dead. It was the Count’s sidekick Orfanik who staged the counterfeit, and he alone was to blame for the conceit.

Now, with applications such as Claude, ChatGPT and Gemini (formerly Bard), Microsoft and Google are tricking us into seeing a living diva where there is none, and amazingly, even after 120 years of familiarity with this kind of tall tale, we still fall for it.

We’ve learned nothing from Jules Verne. We’re still suffering from La Stilla Syndrome.

You might be thinking…

You might be thinking: “Well it’s too obvious, I wouldn’t fall for a crude trick like that”. But the point of Jules Verne’s novel is that even after the mechanism has been revealed, many of the characters persist in believing there was a real ghost - and nothing will dissuade them that the mechanised singer wasn’t a really present human, back from the dead.

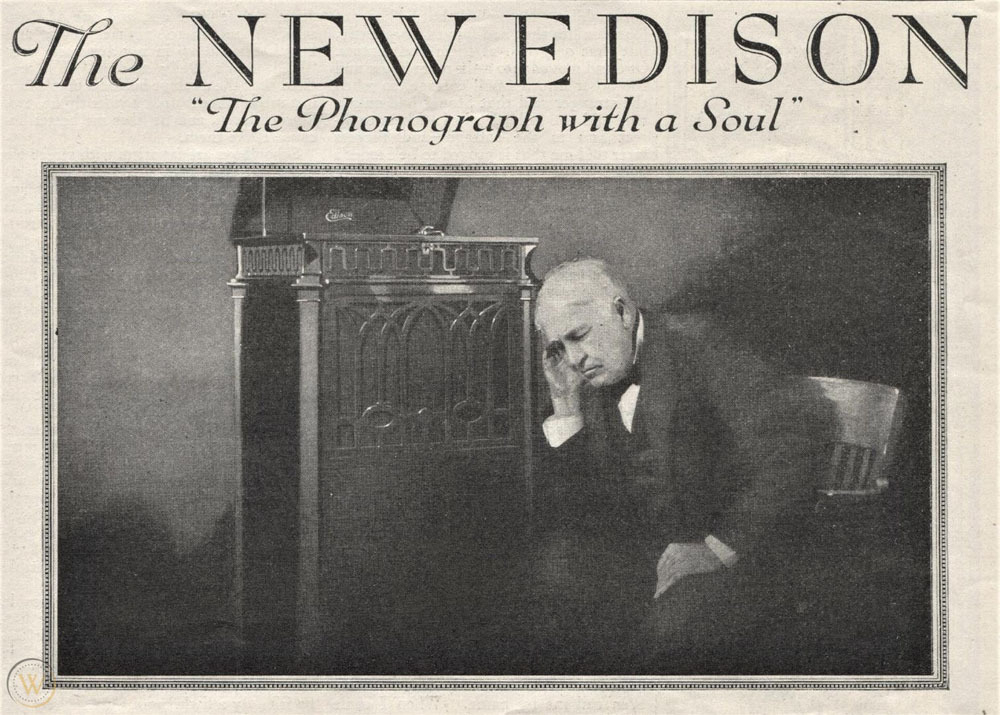

And then you might be thinking, “The phonograph was just a crude recording machine. It was way back in the nineteenth century. That’s completely different from the real technological revolution that AI represents right now”.

If so, you should be aware that the phonograph was a real technological revolution. Thomas Edison wrote an improbably long list of all its possible uses. Every one of them came to pass. The author of a Scribner’s article in 1878, “A Night with Edison’, reported breathlessly:

“The invention has a moral side, a stirring, optimistic inspiration. ‘If this can be done,’ we ask, ‘what is there that cannot be?'” (p.88)

False people should be banned

Given the extent to which people almost want to be fooled, philosopher Daniel Dennett argues that ‘false people’ should be banned. I’m not going to argue with this. At the very least, corporations should immediately stop using the first person pronoun, “I”, in the interface between their chatbots and us, the gullible humans.

No more of Siri ‘saying’:

“I’m a virtual assistant, not an actual person, but you can still talk to me.”

No more obfuscation like this response when I asked Google, “Are you an actual person?”

“I’m really personable. Does that count?”

No, it doesn’t count.

Today, for the first time in history, thanks to artificial intelligence, it is possible for anybody to make counterfeit people who can pass for real in many of the new digital environments we have created. These counterfeit people are the most dangerous artifacts in human history, capable of destroying not just economies but human freedom itself. Before it’s too late (it may well be too late already) we must outlaw both the creation of counterfeit people and the “passing along” of counterfeit people.

Advertisers once claimed the phonograph was so life-like it actually had a soul.

It didn’t then. And AI still doesn’t now.

But if now we can see through the advertising gimmick of a century ago, why are we letting ourselves be fooled by the most recent advertising trick? Is there any cure for La Stilla Syndrome? Or will time, yet again, be the only healer?

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, out now.

See also:

More than ever, embracing your humanity is the way forward.

Despite AI, the Internet is still personal

Since AI can easily write everything correctly with perfect spelling and punctuation, one way to show you’re human is to do the opposite.

The single best way to supercharge your workflow with AI writingslowly.com

Phonographia.com has a long list of ‘phonoliterature’ - books in which a phonograph appears at least once. In fact, Verne’s tale is almost repeated in Arthur Conan Doyle’s much shorter 1899 version, ‘The Story of the Japanned Box’. People were obsessed with this revolutionary technology.