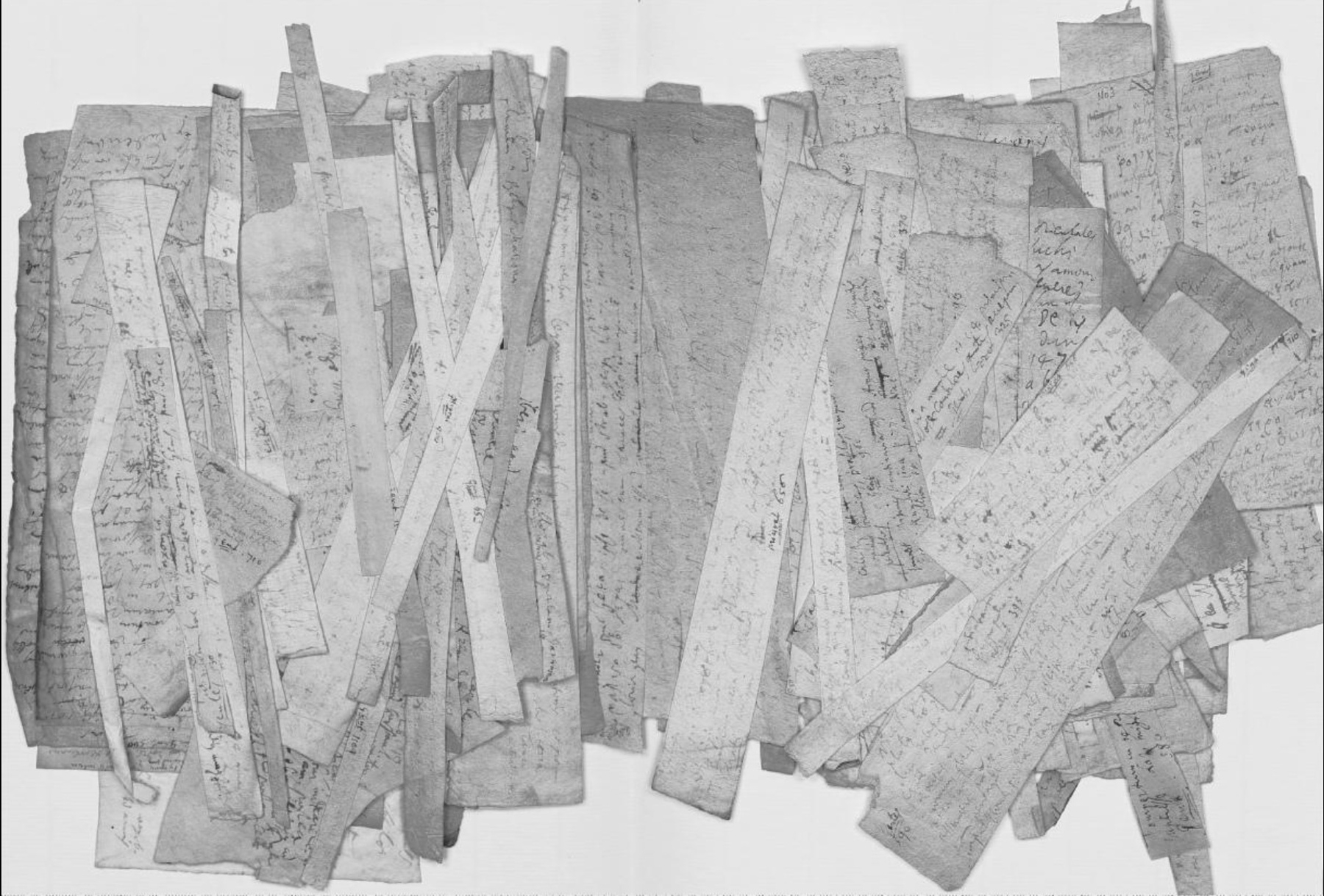

Leibniz created a haystack of notes that wouldn't fit in his Zettelschrank

Gottfried Willhelm Leibniz (1646-1717), that complex polymath who (probably) invented calculus, used to write down all his thoughts then cut up the pieces and attempt to rearrange them. He once admitted this had resulted in “one big chaos”.

Leibniz said he had so many thoughts in a single hour that it took him more than a day to write them all down.

“Sometimes in the morning, in the hour that I spend still lying in bed, so many thoughts come to me that I need the whole morning, indeed sometimes the whole day or even longer, to set them down clearly in writing.”1

These are just a couple of the intriguing facts I learned from reading Michael Kempe’s excellent biography, The Best of All Possible Worlds. A Life of Leibniz in Seven Pivotal Days (Pushkin Press).

Image source: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Bibliothek—Niedersächsiche Landesbibliothek.

Though he wrote and cut up and rearranged mountains of notes, he didn’t publish much in his lifetime.

“I wrote countless things about countless things,” he wrote to the Swiss mathematician Jakob Bernoulli in 1697, “but only published a few about few.” And he told the Hamburg lawyer Vincent Placcius: “If you only know me from my publications, you don’t know me.” 2

All this sounds quite dismal, but on the other hand Leibniz was a genius in several disciplines, who left behind “one of the largest literary legacies of any scholar in world history” (Kempe).

Furthermore, Markus Krajewski, scholar of media history, claims “any history of ‘assisted thinking’ with artificial intelligences finds a worthy starting point in Leibniz.”

Perhaps then his seemingly disorganised notes were just part of the genius.

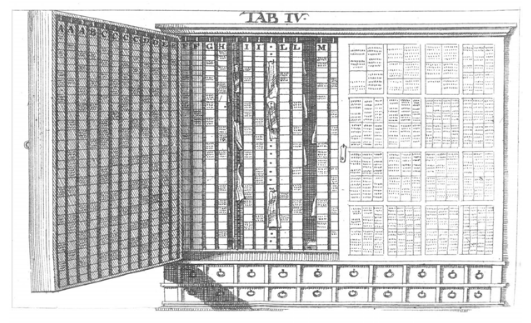

Krajewski’s recent chapter “Intellectual Furniture: Elements of a Deep History of Artificial Intelligence.” sets Leibniz’s endeavours in the context of an intellectual history that stretches from the specialised furniture Leibniz acquired to arrange his notes, via the dawn of the computer age, all the way to the recent rise of artificial intelligence. Heady stuff!

In Hanover Leibniz kept a special cabinet for his notes, where he hung up the notes he had cut up in various combinations. This was his Zettelschrank, modelled on Thomas Harrison’s scrinium litteratum. After his death Johann Friedrich Blumenbach inspected this contraption and called it “the most fearsome and cumbersome machine that one could imagine”3. Well, I don’t know about that. Perhaps he didn’t have a particularly strong imagination.

Image source: Krajewski, p.186

This sense of being almost overwhelmed by information is really the prehistory of the situation we’re in now, where not only is there ‘too much to know’4, but AI is making more and more of it every second. Our information machines aren’t so much helping us to get the chaos under control as simply creating more and more chaos, faster than we can comprehend it, much less organise it.

Yes, we’re drowning in data, but it may be comforting to know that this is nothing new, and that despite the mounds of ‘stuff to know about’, some remarkable breakthroughs were still possible, and may be still. In 2013 Stephen Wolfram visited the Leibniz archives in an attempt to understand how Leibniz had achieved so much so early - and how he had also missed so much of what we now take for granted in the computational perspective on science.

With the utmost presumption, I’ve previously claimed that Leonardo, that other great polymath, might have benefited from a more coherent approach to making notes than his zibaldone. Dare I make the same claim for Leibniz?

Oh look, I just did.

If you like this kind of thing (and who wouldn’t?) why not subscribe to the weekly digest?

References

Kempe, Michael. The Best of All Possible Worlds. A Life of Leibniz in Seven Pivotal Days. Translated by Marshall Yarbrough. London: Pushkin Press. 2025.

Krajewski, Markus. “Intellectual Furniture: Elements of a Deep History of Artificial Intelligence.” Chapter 8 in Bajohr, Hannes, ed. Thinking with AI: Machine Learning the Humanities. First edition. London: Open Humanities Press, 2025. PDF.

‘Leibniz, LLull and the computational imagination’ Public Domain Review.

von Rauchhaupt, Ulf. “Leibniz’ Manuskripte: Schönschrift war nicht seine Sache”. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 2016.

Wolfram, Stephen (2013), “Dropping In on Gottfried Leibniz,” Stephen Wolfram Writings.

-

Leibniz, [no date], LH 41, 10 Bl. 2: “il me vient quelques fois tant de pensées le matin dans une heure, pendant que je suis encor au lit, que j’ay besois d’employer toute la matinée et par fois toute la journée et au de là, pour les mettre distinctement par ecrit.” Cited in Eduard Bodemann, Die Leibniz-Handschriften der Königlichen Öffentlichen Bibliothek zu Hannover 1895 (Hanover: Hahn, 1895), 338. Quoted in Kempe, 2025, ch 1. ↩︎

-

loosely translated from Ulf von Rauchhaupt’s article, “Leibniz’s manuscripts: fair handwriting wasn’t his thing”. ↩︎

-

quoted in Krajewski, p.188. ↩︎

-

Ann Blair’s memorable phrase: Blair, Ann. Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age. New Haven London: Yale University Press, 2010. ↩︎