Influence is everything: novelty its flimsy dress

What happens when once fashionable ideas get left behind?

I’ve often felt the culture moves on too fast, leaving so much on the table in terms of untapped potential. This is certainly true for pop music. Fashions come and go so fast that they leave great concepts stranded in time. You could write a great glam rock song in 2023, but you would have needed at all costs to avoid staying stuck in 1973. The trick is to avoid descending from homage into mere pastiche.

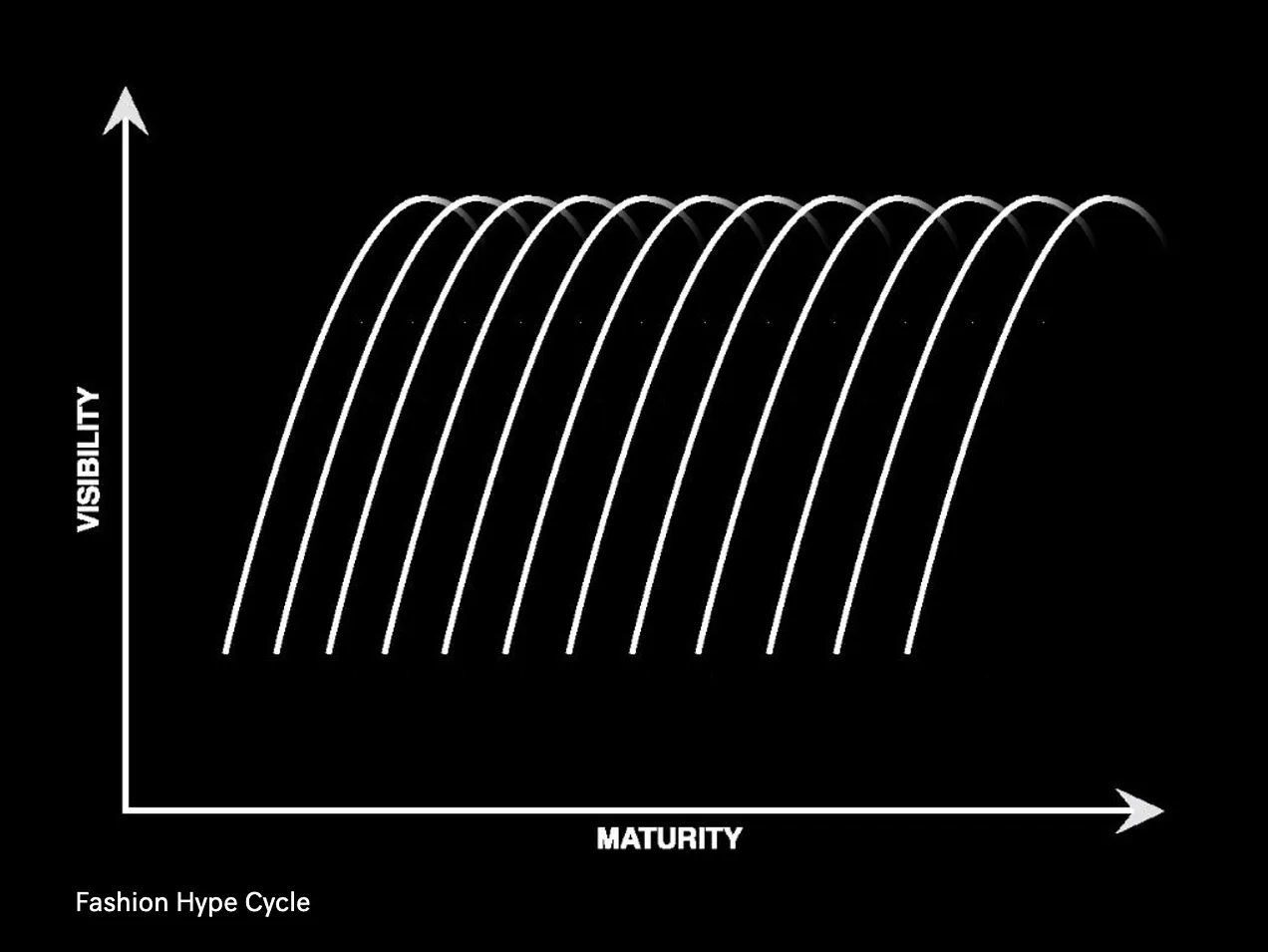

The Nemesis guide to being early described the fashion cycle as an endless process in which “each new thing is supplanted by another new thing, and no linear pattern emerges. Things very rarely reach the plateau of productivity, more often falling straight to Hades through the trough of disillusionment. No one seems to follow up on the hyped project of yesterday.”

But it's worse than that. It's not just that, mysteriously, no one merely *'seems'* to follow up. It feels like **they're not allowed to**.THE NEMESIS GUIDE TO BEING EARLY nemesisglobal.substack.com

Viewed from this perspective, it struck me that the fear of appearing unfashionable is strangely overdetermined in the culture. The Nemesis article compared it to arriving late, as opposed to being early. Oh, the horror! But it’s more serious than that. It’s a genuine, almost palpable, fear - a kind of internalized, psychological self-policing. Whatever you do, don’t be unfashionable.

But what does it really amount to? Whose interests could it possibly serve for us to frighten ourselves into not touching the sacred grave goods of fashions past?

The starting point may be the fear that the market will exclude you and your glam rock hit, that it will be a commercial failure. But the fear runs much deeper than that. What could I have to lose just by listening to such an artifact? The unfashionable carries its own peculiar contamination.

If you liked the Lemon Twigs 2023 album Everything Harmony, and that’s a very big if, you might also like Spilt Milk by Jellyfish and Third Eye by Redd Kross. And if you specifically liked the Lemon Twigs track What you were doing, you might also like pretty much anything by Teenage Fanclub, which is an obvious influence.

The Lemon Twigs don’t so much show their influences as trumpet them from the roof tops. And you might see this festival of ‘Mersey Beach’ homage as hopelessly nostalgic and twee, because what matters, as the Modernists said, is to make it new. But if you do listen to Spilt Milk by Jellyfish (especially ‘Joining a Fan Club’) you’ll notice that it really sounds a lot like Queen, who clearly influenced it, and also a lot like the Ben Folds Five, whom, in turn, it clearly influenced.1

It turns out that influence is everything. Novelty is its flimsy dress.

Perhaps the cultural proscription against appearing unfashionable is a sleight of hand, a way of masking a deeper reality, that almost nothing is new, nothing is original, everything has antecedents. The Lemon Twigs, arguably, get away with it because they’re making a unique selling point out of unfashionable homage. We already know what kind of unfashionable homage we like and it’s tribute bands. The Lemon Twigs are unique because their music isn’t just unfashionable, it’s almost offensively so. In the Spotify era, why listen to them when the entire Beach Boys catalogue is already instantly available? They’re not paying enough tribute.

But then again, they’re not just copying the past. They’re re-examining it, reverse engineering it. It’s as though, from their resolutely analogue studio in a digital era, they’re making the music that might have been made if only the fashion cycle hadn’t consigned all its components into the oblivion of unfashion. It takes a new generation to follow up on the hyped project of yesterday, to uncover what endures.

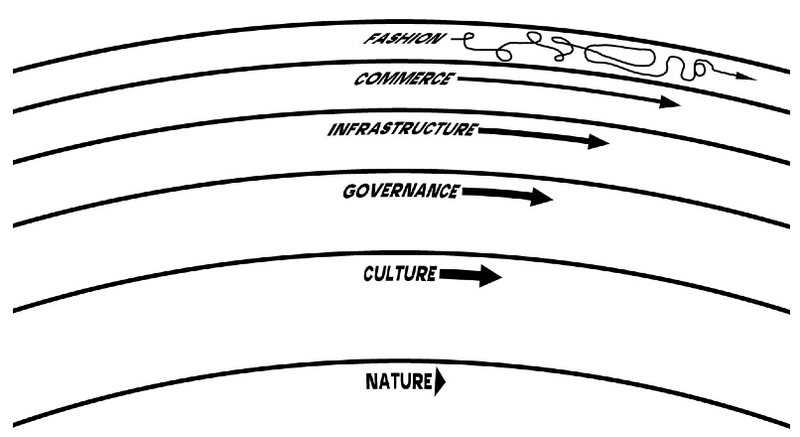

Image: Pace layering, by Stewart Brand.

There’s something to be said for taking a longer look at moments in fashion than the fashion itself ever allowed.

In an article entitled Pace Layering: How Complex Systems Learn and Keep Learning, Stewart Brand claimed:

“The job of fashion and art is to be froth—quick, irrelevant, engaging, self-preoccupied, and cruel. Try this! No, no, try this!”

Well, I’m not so sure. You can enjoy the froth, but unlike art it’s hardly nourishing.

Fashion isn’t only froth, though. It’s an ideology. It’s evidence of faith in infinite potential. Potential, mind, not actuality. That’s the meaning of the scream of the overwhelmed teenager at the Beatles concert, to be abandoned the moment there’s a whiff of reality, or simply the moment the moment has passed.

The task of excavation is to identify the actual (but long abandoned) potential behind the over-hyped promise of infinity.

I’ve written here about the hype cycle of pop music, but it also applies to the hype cycle of your own field of endeavour, whatever it may be. By excavating past fashions, you too might uncover some overlooked nuggets of gold in the supposed dross of the past2. Thanks for reading this far. If you liked it, try the weekly email digest.