Atomic Notes

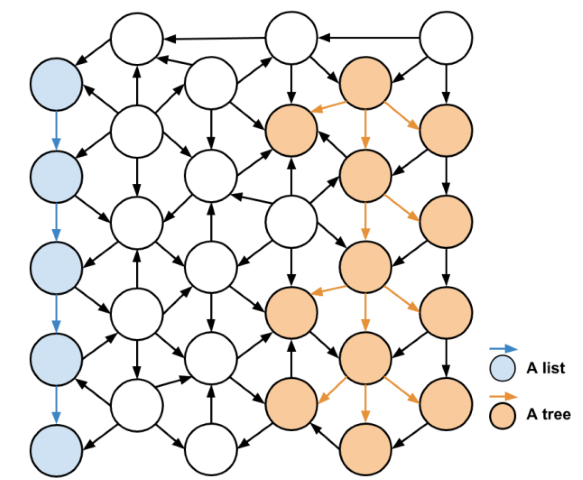

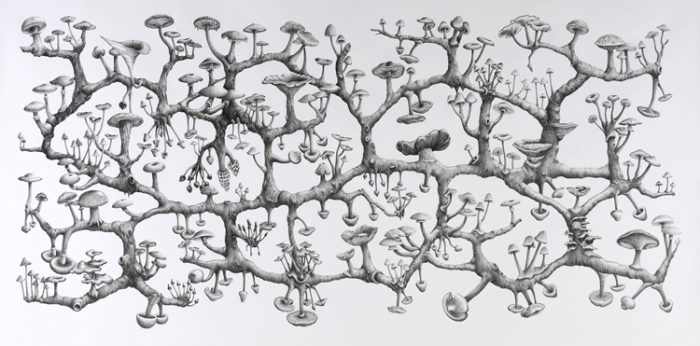

- A network of notes is a rhizome not a tree.

- Manuel Lima on The power of networks (it’s a cool video!)

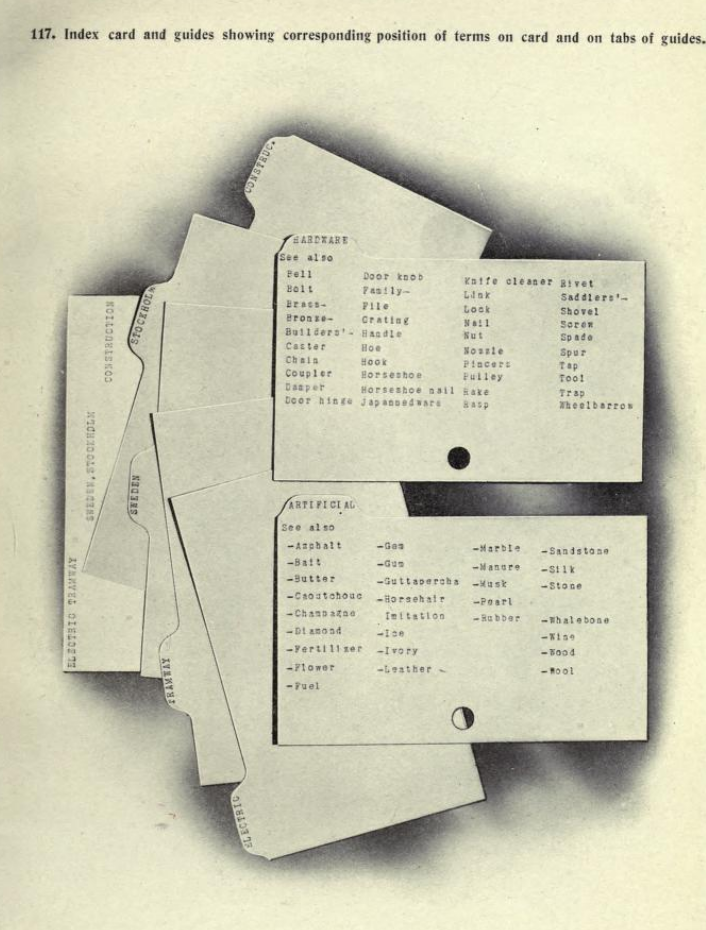

- Top image source: The Card System at the Office by J. Kaiser, 1908.

- Free-form note-making. In this mode, you start with no expectations and just make notes whenever something grabs you. This is great when you don’t yet know what you want to focus on. The risk is you try to read everything, only to discover it’s like drinking the ocean. Ars longa, vita brevis, so you’ll ultimately need to narrow down your field somehow.

- Directed note-making. In this mode, you already know, broadly, what interests you, for example, Richard Hamming’s 10-20 problems. So you make notes whenever something you read resonates with one of your predetermined interests. I used to think I was interested in everything, like Thomas Edison. But after writing notes on whatever took my fancy for a while, I observed that really, I kept revolving around a fairly limited set of concerns. So mostly these days I make directed notes, or else engage in the closely related purposeful note-making.

- Purposeful note-making. This mode is more focused still than directed note-making. Here you have a specific project in mind, such as a particular book or article you want to write, and so you make notes whenever your reading material chimes with what you want to write about. If there’s a risk to this kind of note-making, it’s that in your focused state, you’ll miss ideas that you might otherwise have found worth making notes about.

- N - what larger pattern does this concept belong to?

- S - what more basic components is this concept made of?

- E - what is this concept similar to?

- W - what is this concept different from?

-

you’ll write worthwhile notes that address your own questions and

-

this hook of curiosity will help you remember as you learn.

-

What does the medium enhance?

-

What does the medium make obsolete?

-

What does the medium retrieve that had been obsolesced earlier?

-

What does the medium reverse or flip into when pushed to extremes?

- The search for interconnection

- How to be interested in everything

- Thoughts are nest-eggs

- Serious about a Zettelkasten?

- The card index has triumphed

- We can’t master knowledge

- Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari (2004/1980). Rhizome. In A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi. New York: Continuum, pp. 3-28.

-

a composite name made up of Günter Grass and Max Frisch, with more than a nod to the old Knecht, the Magister Ludi of The Glass Bead Game. ↩︎

- Record your thoughts, one by one.

- “Each thought that is welcomed and recorded is a nest egg…”

- Build up a collection of notes, without worrying about whether they are coherent.

- “…by the side of which more will be laid.”

- Connect your notes, creating a dense network of association.

- “Thoughts accidentally thrown together become a frame in which more may be developed and exhibited

- Construct meaning from your previously disconnected thoughts

- “Thought begat thought.”

-

Manuscript Collection #845, Innis Papers, Archives of the University of Toronto, Thomas Fisher Library, Box 8 ↩︎

- I need a simpler system for online writing. It’s been clear for some time that Wordpress was holding me back. I know: “poor workers blame their tools”, and obviously there’s something wrong with me if I can’t just log in to Wordpress and write a line or two from time to time. But really, it felt as though the user interface was presenting a psychological barrier. Every time I logged in it seemed the WordPress UX had got more complex. Anyway, that’s my excuse. I’m hoping that a switch entirely to micro.blog hosting will help the writing to flow a bit better.

- I like the IndieWeb. Although I had some Indieweb plug-ins set up on my Wordpress site, it didn’t feel as though they were getting much use. The Musky shenanigans at Twitter have made it even clearer that independence on the web is essential and that the true social network is the web itself. Switching to micro.blog will hopefully connect me better, and if I ever change my mind, there’s no lock-in.

- Updating the app feels like a chore. When I checked my hosting dashboard it was clear that there were several insecurities caused by a lack of updating. I just hadn’t gotten around to it for ages. But really, I don’t have much interest in which version of PHP I’m supposed to be using, or what version the plug-ins are - so I’d rather not think about this side of things. If micro.blog can do this for me, I’m not complaining.

- I also quite like Mastodon. Micro.blog has a certain amount of compatability with Mastodon, through the activitypub protocol. So I plan to try that out.

- Writing in Markdown syntax has become more and more intuitive to me, despite its limitations, and I like the relative simplicity of static sites. Micro.blog uses Hugo as its site generator, so now I’m now using Markdown to create static pages.

- for motivation, and

- to leave a record, sharing what I know and

- to encourage you, dear reader, to stop scrolling and go read a good book.

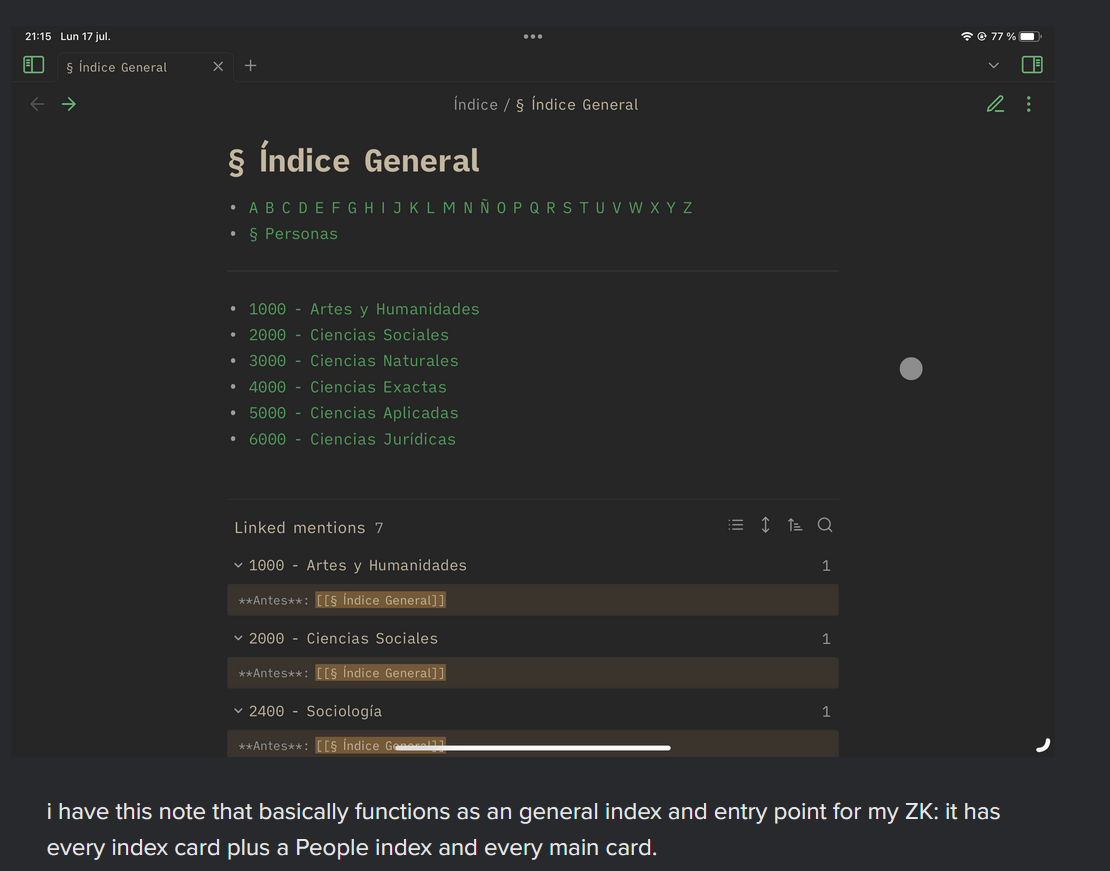

Even the index is just another note

It’s tempting to place your notes in fixed categories

At some point in your note-making journey you’ll notice that quite a few people like to place their notes in fixed categories according to some scheme or other. The ancient method of commonplaces held that knowledge was naturally organised according to loci communis (common places). Ironically, no one from Aristotle onwards could ever agree on what the commonly-agreed categories were. Assigning your notes to categories is consistent with the ‘commonplace’ tradition, but that’s not what the prolific sociologist Niklas Luhmann did with his Zettelkasten, and furthermore it runs exactly counter to Luhmann’s claim in ‘Communicating with Slipboxes’, where he said:

“it is most important that we decide against the systematic ordering in accordance with topics and sub-topics and choose instead a firm fixed place (Stellordnung).”

But there’s no need to despair, there is a way through the impasse! After all, what exactly is a subject or category? The subject or category index itself, it turns out, is nothing other than just another note. Here’s a real-life example:

“i have this note that basically functions as an general index and entry point for my ZK: it has every index card plus a People index and every main card.” - u/Efficient_Earth_8773

When everything’s a note, even the categories are just notes

Why does this matter? If even the index is just a note, then you haven’t constrained yourself with pre-determined categories. Instead, you can have different and possibly contradictory index systems within a single Zettelkasten, and further, a note can belong not only to more than one category, but also to more than one categorization scheme. Luhmann says:

“If there are several possibilities, we can solve the problem as we wish and just record the connection by a link [or reference].”

When even the index is just a note, a reference to a ‘category’ takes no greater (or lesser) priority than any other kind of link. This is liberating. Where a piece of information ‘really’ belongs shouldn’t be determined in advance, but by means of the process itself.

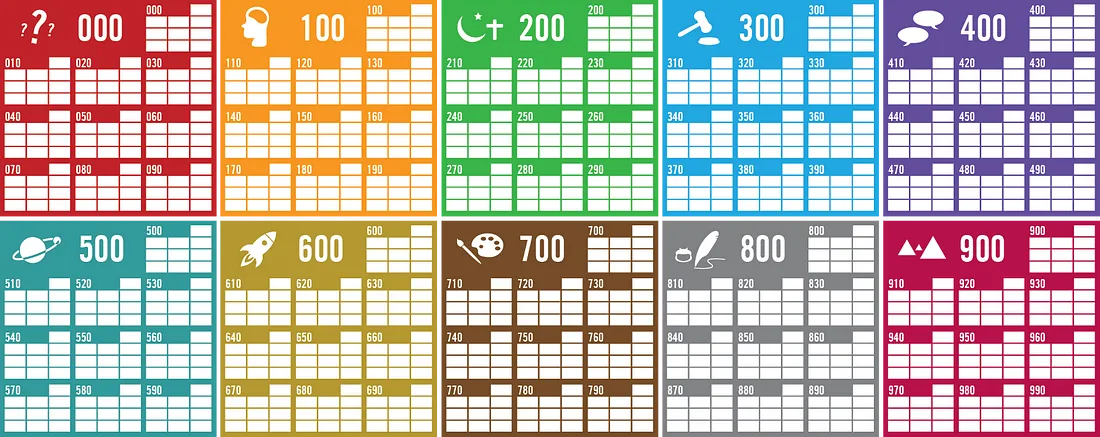

The Dewey Decimal System pigeonholes all knowledge, like cells in a prison.

Some people want an index, like folders in a filing cabinet, or subject shelves in the library. Well they can have it: just write a note with the subjects listed and make them linkable. Some people don’t want this, and they can ignore it. I personally don’t understand why you’d want to set up a subject index that mimics Wikipedia or the Dewey Decimal system, or even the ‘common places’ of old. I’m neither an encyclopedist, a librarian, nor an archivist. What I’m trying to do is to create new work. I want to demonstrate my own irreducible subjectivity by documenting my own unique journey through the great forest of thought. My journey is subjective, because it’s my journey. I’m pioneering a particular route, and laying down breadcrumbs for others to follow should they so choose. It’s unique, not because it’s original but because the small catalogue of items that attract me is wholly original. As film-maker Jim Jarmusch said:

“Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic.” (I stole that from Austin Kleon).

But that’s just me (and Luhmann).

Make just enough hierarchy to be useful

Having thought a bit about this I’m inspired now to sketch my own workflow, to see how it… flows. In general, I favour just enough data hierarchy to be viable - which really isn’t very much at all. I’m inspired by Ward Cunningham’s claim that the first wiki was ‘the simplest online database that could possibly work’. Come to think of it, this may be one of the disadvantages of the way the Zettelkasten process is presented: perhaps it comes across as more complex than it really needs to be. As the computer scientist Edsger Dijkstra lamented,

“Simplicity is a great virtue but it requires hard work to achieve it and education to appreciate it. And to make matters worse: complexity sells better.” - On the nature of Computing Science (1984).

If you must have hierarchies like lists and trees, remember that they’re both just subsets of a network.

Source: I don’t know. If you do, please tell me ;)

See also:

Three worthwhile modes of note-making (and one not-so-worthwhile)

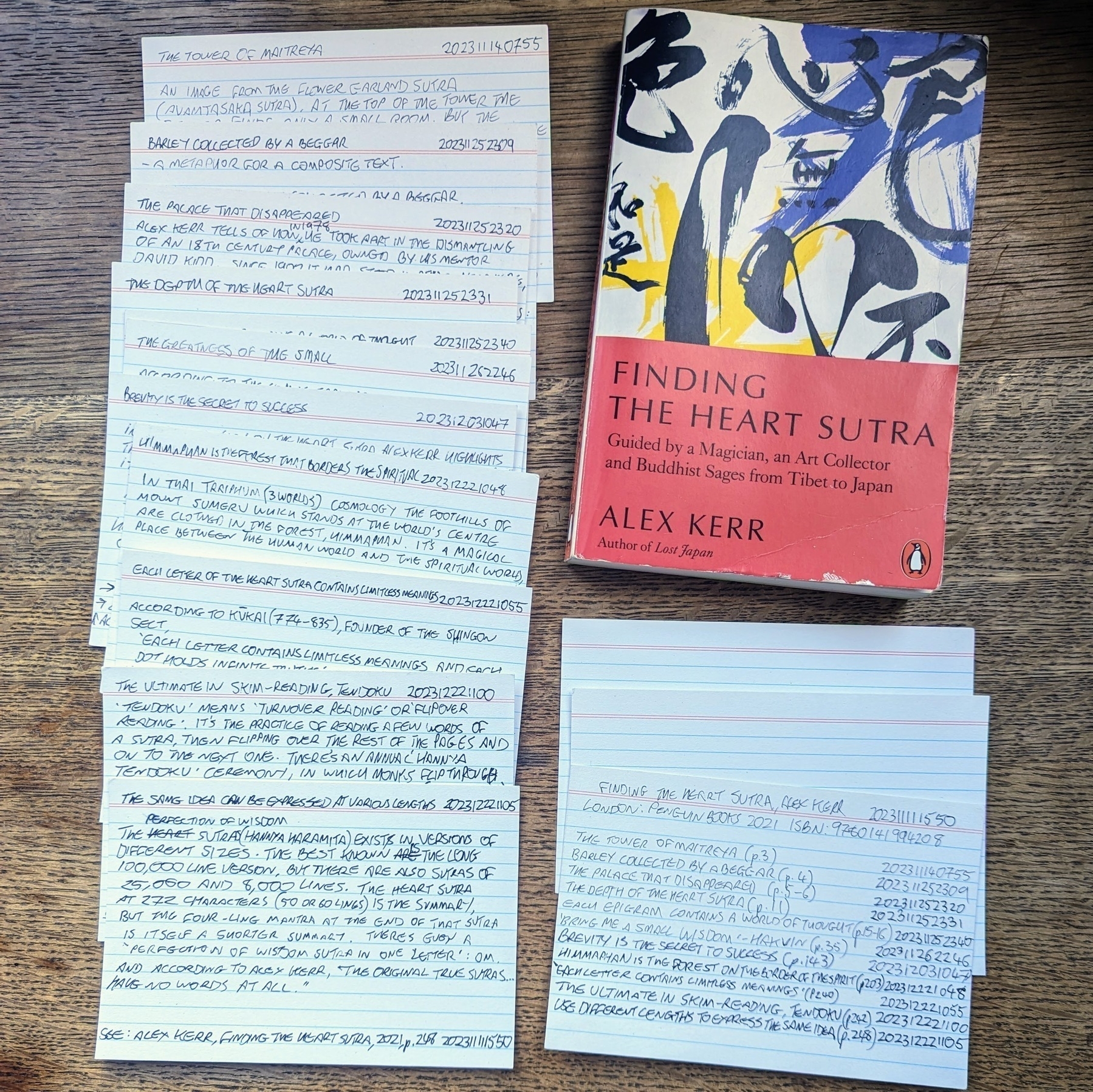

I finished reading Alex Kerr’s Finding the Heart Sutra on New Year’s Eve, so it just scraped into my reading for 2023. And while reading I made notes by hand, as I’ve done before. Although there aren’t very many notes (just eleven, plus a literature note that acts as a mini-index), they’re high quality, since I found the book very interesting.

I don’t mean I’ve written objectively ‘good’ notes. Rather, I mean the notes are high quality for my purposes. Everyone who reads with a pen in hand is an active reader, so the notes one person makes will be different - perhaps completely different- from the notes another person makes. In any case, no two readers read a book the same way.

Reflecting on this it seems to me there are at least three fruitful ways, or modes, of making notes while reading, as follows: Free-form, directed, and purposeful note-making.

Each of these note-making modes has its place, but in this particular case I was reading Finding the Heart Sutra with a very specific project in mind. So the notes I made were also quite specific. I imagine that someone else would be surprised by the notes I made, since they don’t really reflect the contents of the book. For instance, my notes are definitely not a summary of the book’s contents. Nor do they even follow the main contours of the book’s themes. Instead, I was making connections while reading with the main concerns of my own project. Each of my notes stands in its own right and could potentially be used in a variety of different contexts, but collectively, they make sense in relation to my own preoccupations. They fit into my own Zettelkasten, and no one else’s.

“Most great people also have 10 to 20 problems they regard as basic and of great importance, and which they currently do not know how to solve. They keep them in their mind, hoping to get a clue as to how to solve them. When a clue does appear they generally drop other things and get to work immediately on the important problem. Therefore they tend to come in first, and the others who come in later are soon forgotten. I must warn you, however, that the importance of the result is not the measure of the importance of the problem. The three problems in physics—anti-gravity, teleportation, and time travel—are seldom worked on because we have so few clues as to how to start. A problem is important partly because there is a possible attack on it and not just because of its inherent importance.”

If you want to know more about how to read a book, you could do worse than read How to Read a Book, by Mortimer Adler. It’s not the last word on the subject, but it’s a good starting point.

And it’s a warning against a fourth mode of note-making that I don’t advise: encyclopedic note-making. This is where you read a book and try to write a summary that will work for everyone. First, it’s hard work, and secondly, it’s probably already been done. If you open the link above you’ll see that the Wikipedia entry for How to Read a Book already includes a summary of the book’s contents. There are circumstances where the careful and complete summary is worthwhile, but I suggest you only start this task with the end - your own end - in mind.

If you have thoughts about making notes while reading, I’d be very interested to hear about it.

See also:

A note on the craft of note-writing

Learning to make notes like Leonardo

How to make the most of surprising yourself

Your collection of linked notes, your Zettelkasten, isn’t a ‘second brain’, as though it were separate from your first, actual brain. Rather it is part of your extended mind, which your brain creates constantly by co-opting its wider environment into its own processing activity. Brain and environment together create mind. In the case of the Zettelkasten it’s a very deliberate extension of the brain, with a few simple but powerful generative rules.

One of the interesting features of this deliberately extended cognitive tool is its ability to present you with surprises. Reading through old notes, for example, you may be surprised that you ever wrote this. And re-reading your work in the light of new information, you may have new flashes of inspiration or see new connections that weren’t previously visible. Or perhaps the juxtaposition of two seemingly unrelated notes will prompt you to create a third, which contains an entirely new idea.

In this sense, your notes become a kind of conversation partner, reminding you of what you once thought, and even challenging you to go further. It’s a living thinking environment, an ever-evolving ‘connectome’, which sometimes appears to have a life of its own.

Why not surprise yourself?

Philosopher Andy Clark is quite well known for claiming that the human mind extends beyond the brain, and that “human brains spawn and maintain extended human minds”.

In a podcast interview with Sean Carroll, he recommends artificially curating environments in which we can surprise ourselves. This temporary increase in uncertainty, he claims, reduces prediction error in the long term.

“it looks as if very often, the correct move for a prediction-driven system is to temporarily increase its own uncertainty so as to do a better job over the long time scale of minimizing prediction errors, and that looks like the value of surprise, actually, and that we will… I think we artificially curate environments in which we can surprise ourselves. I think, actually, this is maybe what art and science is to some extent, at least, we’re curating environments in which we can harvest the kind of surprises that improve our generative models, our understandings of the world in ways that enable us to be less surprised about certain things in future.”

Clark refers to the work of Karin Kukkonen, a literary scholar who has applied the idea of predictive processing to literature. This reminded me of Steven Johnson’s suggestion in his book, Farsighted that a good novel is a decision-making simulation. He extolls the sophisticated decision-making conundrums of the characters in George Eliot’s Middlemarch, over the simpler black-and-white decisions of Charles Dickens' characters.

So perhaps the surprise function of the Zettelkasten is more useful than at first appears. It isn’t merely an aid to memory, or a handy conversation partner, or a writing prompt. On Clark’s account, it may also enable precisely the kind of surprises we need and can learn from in order to understand the world better.

Of course, we constantly encounter surprises in everyday life, and sometimes learn from them too. But viewed through the ‘predictive, extended mind’ lens, the Zettelkasten presents a precise, controlled and deliberate laboratory for cultivating such a learning process.

I wonder how your notes have surprised you. Please let me know.

Some resources

Andy Clark on the Extended and Predictive Mind - [Sean Carroll’s Mindscape: Science, Society, Philosophy, Culture, Arts, and Ideas] (https://www.preposterousuniverse.com/podcast/2023/04/27/235-andy-clark-on-the-extended-and-predictive-mind/)

Clark, Andy. 2022. Extending the Predictive Mind, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, DOI: 10.1080/00048402.2022.2122523

Johnson, Steven. 2018. Farsighted : How We Make the Decisions That Matter the Most. New York: Riverhead Books an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

Kukkonen, Karin. 2020. Probability Designs: Literature and Predictive Processing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780190050962

See also

A network of notes is a rhizome not a tree

Learning to make notes like Leonardo

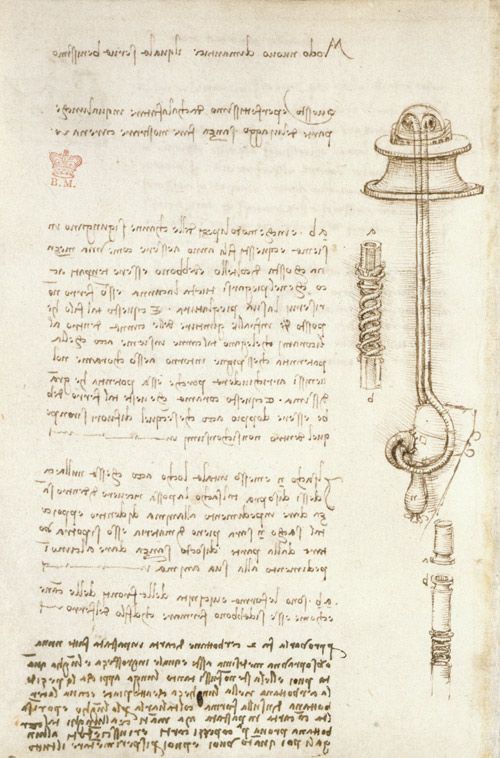

Leonardo wrote on loose sheets of paper

The Codex Arundel, a notebook of Leonardo Da Vinci, is not what it first appears. It isn’t a notebook that Leonardo used. For the man himself it wasn’t a notebook at all. It’s a collection of individual notes, bound for convenience only after his death. The British Library webpage observes:

“The structure of the notebook reveals that it was not originally a bound volume. It was put together after Leonardo’s death from loose papers of various types and sizes, some indicating Leonardo’s habit of carrying smaller bundles of notes to document observations outdoors.”

He wasn’t the first to adopt this habit. Beginning in the Fourteenth century it had become something of a fashion for Italians to create their own ’zibaldone’, a hodgepodge of notes on diverse subjects. Leonardo wrote of his notes:

“This is to be a collection without order, drawn from many papers, which I have copied here, hoping to arrange them later each in its place, according to the subjects of which they treat.”

The same is true of the Forster Codices, in the care of the Victoria and Albert Museum: they weren’t originally codices (books), but unbound notes.

“Leonardo probably worked on loose sheets of paper (bought at one of Milan’s many stationers' shops), which he carried about with him to record his observations. His papers were at some stage folded into booklets and later bound, possibly under the ownership of the Spanish sculptor Pompeo Leoni (1533 – 1608).” (https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/leonardo-da-vincis-notebooks)

Many of the notes in the Codex Arundel were written in 1508, but they span most of Leonardo’s career.

The notes cover a very wide range as well as references to many different subjects. They include sketches of a mechanical organ and of an underwater breathing apparatus, There are notes and diagrams on mechanics, lists of proverbs and riddles, sketches on bird-flight, a household inventory, notes on optics and mirrors for producing heat, calculations on balances and weights, a plan for an urban quarter, and for a complete city, notes on the acoustics of drums and wind instruments, notes on river dynamics and on geometry, and a sketch of a cockleshell.

Leonardo Da Vinci - master of making notes

Here’s the German scholar Hektor Haarkötter, writing about the note-making expertise of Leonardo Da Vinci:

“Leonardo is the early master of the note [Nottizettel]. Today da Vinci is famous as an artist and painter, inventor and designer. However, he was not very productive as a public artist. Only about fifteen paintings that can be proven to have been created by him have survived, some of them in very poor condition or never completed. Leonardo da Vinci was really productive, however, in the privacy of his writing. He left behind over 10,000 sheets, drafts, scraps, snippets, sketches, papers, pages and slips of paper. (Many have been transcribed in Theodor Lücke, Leonardo da Vinci. Tagebücher und Aufzeichnungen. Leipzig, Paul List Verlag, 1953)

And this is only the part of his many records that have come down to us. Through his papers we know of other ledgers, notebooks, and codices, but they have disappeared, been scattered, torn apart, sold off, or in one way or another through the course of time, simply destroyed. How large the number of those records is of which we have no, well, note, is incalculable.

Already in Leonardo’s work all the characteristics of the note [Nottizettel] as a private medium are visible. He wrote in a code so that unauthorized eyes could not have read his notes. The universality of writing materials and forms of writing corresponded the universality of the subjects. From word lists and shopping wishes to technical drawings and philosophical notes to obscene and pornographic sketches. None of them was intended for the public, and the Renaissance master never published a book. He would hardly have been able to do so, he admitted to himself in his notebooks, which today are traded at astronomical prices at auctions, but which themselves lost an overview of his records.

What remains?

The amazing thing about the inconspicuous medium of notes is that from a hodgepodge of notes in the writing practice of writers and scientists, a completed book can emerge in the end. However we must not forget that, as a rule, only a small part of the notes, as a preliminary stage, finally ends up in the work. The larger part of such paralipomena [supplementary material, literally ‘things omitted’] remains, is never used, is hardly ever read again, and is often discarded and thrown away. Or the notes end up in the archives, where they are preserved as cryptic manuscripts, in worm-eaten folders or as messy single sheets, where they can enjoy the security of all basement magazines, never again to be viewed by human eyes. Notes are communicants after all without communicating. The path to the finished book is paved with media corpses.”

Source: Hektor Haarkötter, «Ich notiere, also bin ich» Notizen als Medien des Denkens Passim 28 (2021) Bulletin des Schweizerischen Literaturarchivs, p.4-5. Available at: <www.nb.admin.ch/snl/de/ho…> Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator and a bit of imagination.

What can we learn from Leonardo’s approach to making notes?

Write everything down

Make notes. you never know when you’ll invent a diving mechanism, or a flying machine, or who knows what else? Toby Lester, author of Da Vinci’s Ghost, claims, “Whenever something caught his eye he would compulsively open a small notebook that he wore hanging from his belt and begin sketching furiously, with almost mind-boggling virtuosity. He loved his tiny sketchbook and recommended that all serious artists carry one.” “These things should not be rubbed out,” wrote Leonardo, “but preserved with great care, for the forms and positions of objects are so infinite that the memory is incapable of retaining them”. Leonardo plainly wrote (and drew) in order to think - and you can too.

Use your memory too

Don’t expect your note system to remember things for you. There is a view that writing helps you to remember. But Hektor Haarkötter calls this ‘a myth of the media’. “In fact,” he says, “there is hardly a more effective way to erase a thought from memory than to write it down. The problem of remembering is not solved by taking notes, but only delegated, namely from “What did I want to remember?” to “Where did I write it down?” And the larger the volume of notes, the smaller the probability of finding a specific note again.” So making a note is primarily the act of thinking itself, not a primarily a way to remember what you thought.

Do what works for you

Loose leaf pages worked for Leonardo, and he wrote thousands of them. He had a system that enabled him both to think and to capture his thoughts. Don’t wait for the ideal system to appear, when an OK one will do. And don’t over-complicate things. He didn’t have a Moleskine notebook, or Obsidian software. He just wrote.

Don’t put off the organisation for another time

Don’t put it off, because that day may never come.

Leonardo intended “to arrange them later each in its place, according to the subjects of which they treat”, but as far as we can tell, he never did. This is possibly a reference to the then popular practice of arranging notes in ‘loci communis’, or commonplaces - so called because there were several different standard systems of thematic arrangement by category. He didn’t get round to it. And later editors didn’t have much idea of what order to put his notes after he was gone. Who knows what he might have finished if he’d been a bit more organised at the outset. Don’t put off the organisation of your notes, because it will probably never happen.

Publish, by any means necessary

Notoriously, Leonardo hardly finished anything. Some of this, such as the unfinished painting now known as Mona Lisa, may have been deliberate. But on his death, Leonardo left his notes to his faithful pupil Francesco Melzi, who then left them to his son. The son didn’t value them at all and abandoned them to molder in an attic, so it’s amazing any of these now priceless notes survived at all. In fact the reason Leonardo is best known as an artist, which was not his main occupation (in 1482 he put at the very bottom of his resume for the Duke of Milan, “also I can do in painting whatever may be done”), is that the notes were effectively lost for generations and only really came to attention in later centuries. Don’t put off the publishing of your knowledge. Your pupils' children might not follow your instructions any more than Leonardo’s did. Share what you know with others. Don’t expect it to outlive you. Seize the day. You might think you’re no Leonardo. That’s right. You’re not. You are you, and that’s exactly what the world needs.

Furthermore, it’s so much easier to publish these days than it was at the time of Leonardo. There’s hardly any excuse not to press ‘send’.

There might just be a better system

I hesitate to try to improve on arguably the greatest genius of all time, but with the greatest presumption, here goes. Leonardo himself called his notes ‘a collection without order’, and perhaps a modicum of order might heave helped him. The system he never got around to using was that of ‘commonplaces’, extremely widely used during the Renaissance and for centuries after. The idea was that you’d catalogue your notes according to a more-or-less standard set of locations (i.e. common places). There are a few problems here.

First, it’s hard and uninteresting work to catalogue all your thoughts into predetermined folders like this. Perhaps that’s why Leonardo didn’t do it. Maybe it was just not important enough.

Second, even if you do want to file your notes, it’s not universally agreed what the folder names should be. Through the ages there have been numerous attempts to design a standard set of commonplaces, and none of them have stuck. One such is the Dewey Decimal System, often used for cataloguing library subjects. Not even all the libraries follow this particular system. Wikipedia has a list of ‘main topic classifications’, too. Though you might not know this, you probably haven’t suffered from your ignorance on this matter. To the ordinary Wikipedia user, it doesn’t really seem to make much difference.

Third, keeping your ideas in the categories within which they were formed tends to limit innovation and re-combination. For example, a folder of notes labelled ‘psychology’ doesn’t really tell you much and it keeps your psychology ideas artificially separated from your thoughts on art, or sport, or jokes. In fact, any categories tend to damp down the creative spark. Perhaps that’s why Leonardo’s ‘collection without order’ worked for him.

More resources

The Codex Arundel is at the British Library and online.

David Kadavy has a great podcast episode about Leonardo: Leonardo Mind, Raphael World – Love Your Work, Episode 290 Ironically, Kadavy sees Leonardo as ‘the greatest procrastinator who ever lived’. It’s ironic because, well, it’s Leonardo.

Hektor Haarkötter’s book on notemaking includes more on Leonardo as well as a host of other characters, but Notizzettel is currently only published in German.

And if you’ve read this far, you’ll love Gillian Hess’s Substack blog, Noted. She has already written plenty about Leonardo, which you can read by subscribing.

Meanwhile, on this site, I’ve also written about Aby Warburg’s compulsion to make notes, and about Ted Nelson’s evolutionary file list, and about the writing process of Henry Thoreau - and probably lots more about Zettelkasten I’ve forgotten about.

A note on the craft of note-writing

An fairly new article from Brazil caught my eye, on note-writing as an intellectual craft. It highlights the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann’s note-making process (he put his many linked notes in a Zettelkasten - an index box).

Cruz, Robson Nascimento da Cruz, and Junio Rezende. “Note-writing as an intellectual craft: Niklas Luhmann and academic writing as a process.” Pro-Posições 34 (2023).

<doi.org/10.1590/1…>

https://www.scielo.br/j/pp/a/L7gmq6W7bvzgn984hSJ94

Abstract: "Despite numerous indications that academic writing is a means toward intellectual discovery and not just a representation of thought, in Brazil, it is seen more as a product of studies and subjects than an integral part of university education. This article presents note-taking, an apparently simple and supposedly archaic activity, as a way through which academic writing is eminently oriented towards constructing an authorial thought. To this end, we discuss recent findings in the historiography of writing that show note-taking as an essential practice in the development of modern intellectuality. We also present an emblematic case, in the 20th century, of the fruitful use of a note-taking system created by German sociologist Niklas Luhmann. Finally, we point out that the value of note-taking goes beyond mere historical curiosity, constituting an additional tool for a daily life in which satisfaction and a sense of intellectual development are at the center of academic life."

If you live your life in chunks, what size should they be?

Life tends to be lived in chunks. Hours, days, weeks, months, seasons, years - these are familiar if slightly artificial concepts. But what’s the best-sized chunk of life to focus on? Some would advise living in the moment, by which they don’t really mean the 86,400 seconds that are available in a single day. They effectively mean no chunks at all (or infinite chunks, perhaps).

Reading an article on why you should divide your life into semesters reminded me that I’ve already come across this idea in the shape of the book The Twelve Week Year. I actually bought The Twelve Week Year for Writers, which I’ve skimmed but haven’t read properly yet. I’d like to have a structure to my year that’s more than just “get through it”. But I’m daunted by the thought of needing something concrete to show for my time spent on earth. What did you achieve in your chosen chunk of life? This question won’t be answered by heartbeats or breaths, by sunsets or swims. It would be OK maybe if it could be answered with dollars, but that’s not really acceptable either. It’s too soulless. The question, what did you achieve? needs actual achievements. It needs productivity of the sort I’m not very available for.

@visakanv says “the meandering mind is a feature not a bug”. Why can’t I accept this? Perhaps because I keep putting myself in situations where the meandering mind is a bug not a feature?

I can just about manage to write a short note like this. And then another one… and so on. Austin Kleon calls this “Sisyphus mowing the lawn”. And indeed, I’m happy writing my short notes. If I can’t manage to organise my life into semesters, perhaps I can organise it into atomic notes - the shortest possible viable writing session.

I saw on the zettelkasten.de forum that some members log their note-making productivity on a 10-day rolling tally. One person has written 16 notes in ten days, another has written 33.

They are inspired, as am I, by Sonke Ahrens' exhortation to work as is nothing counts other than writing (well, some of them are).

"If writing is the medium of research and studying nothing else than research, then there is no reason not to work as if nothing else counts than writing.

Focusing on writing as if nothing else counts does not necessarily mean you should do everything else less well, but it certainly makes you do everything else differently.

Even if you decide never to write a single line of a manuscript, you will improve your reading, thinking and other intellectual skills just by doing everything as if nothing counts other than writing."

I’d like to know what kinds of time you find yourself dividing your life into. Do you mainly live in days, or mainly in hours, or perhaps weeks? Do you instead devote yourself to living in the moment? If so, which moment?

#reading

How to connect your notes to make them more effective

A linked note is a happy note

A great strength of the Zettelkasten approach to writing is that it promotes atomic notes, densely linked. The links are almost as valuable as the notes themselves, and sometimes more valuable.

But once you’ve had an idea and written it down, what is it supposed to link to? Is there a rule or a convention, or do you just wing it?

How are you supposed to make connections between your notes when you can’t think of any?

When I started creating my system of notes I didn’t know how to make these links between my atomic ideas, and this relational way of working didn’t come naturally to me. I would just sit there and think, “what does this remind me of?” Sometimes I’d come up with a new link, but more often than not, I didn’t. The problem is, the Zettelkasten pretty much relies on links between notes. An un-linked note is a kind of orphan. It risks getting lost in the pile. You wrote it, but how will you ever find it again? And if you do somehow stumble upon it again, it won’t really lead anywhere, because you haven’t related it to anything else.

Fortunately, there are some helpful ways of coming up with linking ideas that can really aid creative thinking and unlock the power of connected note-making.

Make a path through your notes with the idea compass

Niklas Luhmann, the sociologist who famously (to nerds) kept a Zettelkasten, didn’t exactly say this, but each atomic note already implies its own series of relations. Each note can be extended by means of the idea compass - a wonderful idea of Fei-Ling Tseng, as follows:

Notice how the first two questions promote a tree-like hierarchical structure, with everything nested in everything else, while the second two questions promote a fungus-like anti-hierarchical structure, with links that form a rhizome or lattice. Alone, the former structure is too rigid and the latter is too fluid. But put them together and they can be very powerful. The genius of the Zettelkasten system is that it absorbs hierarchical knowledge networks into its overall rhizomatic structure, without dissolving them, and allows new structures to form (Nick Milo helpfully calls these ‘maps of content’).

Find the larger pattern

Each atomic idea might be thought of as part of a larger pattern. In a sense, every note title is just an item in a list that forms a structure note at a level above it. Say I write a note on ‘functional differentiation’. I realise that this is just one component of a structure note that also includes ‘social systems’, ‘communication’, ‘autopoeisis’ and so on. I write this list, call it ‘Niklas Luhmann - key ideas’, and link it to my existing note. Now I have some ideas for some more notes to write. But will I write them all? No - I’ll only pursue the thoughts that actually interest me, or seem essential. The rest can wait for another day. Actually, I’m suddenly intrigued by what you could possibly have instead of functional differentiation (i.e. what is this note different from?), so I write a new note called ‘pre-modern forms of social structure’ - and link it back to my ‘functional differentiation’ note.

Look for the basic components

Going even further, the atoms, which seemed to be the smallest unit, turn out to be made of sub-atomic particles and so on, all the way down to who knows what (well, particle physicists might know, but I don’t). That means each atomic idea is really just the title of a structure note that hasn’t been written yet. So I take a new note and write: ‘Functional differentiation - the key points’. I imagine this new structure note to be like a top-ten list of important factors, each one ultimately with its own new note - but I’m not going to force myself to write about ten things that don’t matter, just what I find interesting.

When making links, trust and follow your own interest

It’s really important that you don’t try to answer all four questions with a new link. You’re not creating an encyclopedia. Instead, you should only make the connections that actually matter to you. The trace of your own inquisitiveness through the material is, in itself, important information. If it doesn’t matter to you, don’t write about it! Since the notes are atomic, and the possible links increase exponentially (?) the possibility space you are opening up is almost infinite and it can feel overwhelming. So just go with the flow. The key is to find your own curiosity and run with it. That way (as I’ve said before):

That’s what I’ve been doing this morning. At no point have I stopped to think “what shall I write next?” In this sense, the Zettelkasten is a kind of conversation partner. Niklas Luhmann said he only ever wrote about things that interested him. This seems unlikely until you try it for yourself.

And if you keep asking yourself these questions, you’ll find that over time the linking starts to come naturally. It will be increasingly obvious to you what relationships matter. The questions in the idea compass will become intuitive and fade into the background. Well, that’s my experience, but YMMV.

Apply a framework that intrigues you

Another way of making connections, besides the idea compass, is to apply a conceptual framework (or mental model) that interests you - and see where it leads. Here’s an example: Marshall McLuhan’s tetrad of media effects.

The idea here is that any new technology changes the whole landscape or ecology, by bringing some features into the foreground and pushing others into the background. It’s called a tetrad because there are four questions to ask of a new technology:

(This really clicked for me when I puzzled over why my kids don’t use smart phones for talking to people. It seemed crazy to me, but then I looked at question 3 and realised the new technology had retrieved asynchronous communication, which the telephone had previously made obsolete. But I digress.)

Anyway, I’m suggesting you might be able to take these four questions and ask them of the ideas in your notes. For each atomic note: what does this idea enhance, make obsolete, retrieve, or reverse?

Another simple but powerful example is Tobler’s law: “I invoke the first law of geography: everything is connected to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things”. What would it be like if you made everything about physical location?

It’s important to say these are just examples, and they may not work for you. Nevertheless, you may be able to think of frameworks from within your own line of work that allow you to ask a similar set of questions about your ideas. In my experience these frameworks are everywhere and yet are quite under-used.

This article is a lightly edited version of a Reddit comment.

You might also like to read about how a network of notes is a rhizome not a tree.

TiddlyWiki is a really useful writing tool

I use Tiddlywiki as a writing tool, and as a heavily customised Zettelkasten (an ‘index box’ of notes). I love how readily this toolkit can be tailored to suit my workflow and requirements. That means there isn’t really a best version, since it can become what you make of it. I was slightly confused when I started, since it’s different from other writing tools. But you can just start simple and slowly add the functionality that you like to use. Reminding myself to document all my changes and experiments, inside my TW, really helps. Superficially, it’s just a wiki app, but there’s so much more to it than that.

I find Soren Bjornstad’s online version,Tzk, very inspiring. It really shows some amazing possibilities for a personal Zettelkasten-style notebook. His GrokTiddlyWiki tutorial is fabulous too, but it’s a bit of a rabbit hole. Maybe better to just get started and then do the tutorials.

I love the look of Projectify and have used the notebook palettes that it comes with.

To enable backlinks I have found a couple of basic plug-ins really useful and would strongly recommend:

This adds a footer to your notes to show backlinks and freelinks.

This enables automatic renaming of titles and other items across links.

For a to-do list, I greatly admire Projectify, but what I actually use is the simple but effective Chandler, written by the late Joe Armstrong. He talks you through how he wrote it, which in itself is a masterclass in how to customise TiddlyWiki.

Finally I’ll mention the active and very helpful user forum.

If you’d like to discuss any aspect of TiddlyWiki or note-making generally, I’m all ears.

Ted Nelson's Evolutionary List File

Rick Wysocki has a great post introducing Ted Nelson’s innovative idea for a new kind of file system. New, at least, in 1965.

Ted Nelson’s Evolutionary List File and Information Management

In many ways though, we’re still waiting for this kind of approach to become available.

The 1965 paper begins with a programmatic statement that has still not been fulfilled:

“The kinds of file structures required if we are to use the computer for personal files and as an adjunct to creativity are wholly different in character from those customary in business and scientific data processing. They need to provide the capacity for intricate and idiosyncratic arrangements, total modifiability, undecided alternatives, and thorough internal documentation.”

Ted Nelson, in case you don’t know, was the first person to coin the term ‘hypertext’, and this is the first published reference to hypertext. In his post, Wysocki reflects on the connections across decades between Nelson’s ideas and the contemporary interest in ‘personal knowledge management’ and Niklas Luhmann’s non-hierarchical Zettelkasten system of notes. He sees the Zettelkasten as potentially more creative than many contemporary systems because it doesn’t impose a fixed system of categories from the top down.

“Creating hierarchies and outlines of information can be useful, but many don’t realize that outlines have to work on existing material; they are not creative practices themselves (Nelson 135b). This is why the common myth we tell ourselves and our students that an outline should be worked on before writing at best makes little sense and at worst is cruel; how can we outline ideas we haven’t created yet?”

He praises Nelson’s list file approach, where everything is provisional, and can be changed. Fixed categories are out; lists are in. Nelson saw his hypothetical system as a kind of ‘glorified index file’, which is where the connection with Niklas Luhmann’s (quite different) approach comes in. Sadly, most attempts at providing computerised tools for writers have thrown out the affordances that previous analogue systems offered, almost without noticing their loss. Nelson’s ‘Project Xanadu’, notoriously, was never completed. But there are some gains. I’m reminded of TiddlyWiki, in which nearly everything is a list, even the application itself.

The original paper , ‘Complex Information Processing: A File Structure for the Complex, the Changing, and the Indeterminate’, can be found online as a PDF.

A Network of notes is a rhizome not a tree

The Zettelkasten is not just an outline

The Zettelkasten approach to making notes and writing is not the same as creating a standard outline. An outline is basically linear and hierarchical. It’s a tree-like structure. It’s ‘arborescent’. The Zettelkasten on the other hand is a non-linear, non-hierarchical network, that includes hierarchical and linear structures, but is not bound by them. The Zettelkasten is more like a ‘rhizomatic’ structure. It has many connections, but no obvious central trunk. It’s like ginger.

The Zettelkasten can include outlines

The process of writing an article or book might well involve preparing an outline (e.g. a table of contents), but this is done from the contents of the Zettelkasten, not directly by the Zettelkasten itself. The idea is for the Zettelkasten to maintain a more fluid structure than a hierarchical outline, to allow idea formation, prior to the composition of a tightly-structured argument. I do have tables of contents, structure notes, ‘maps of content’, hubs, indices, etc. within my Zettelkasten, but ultimately each of these is just another note in the wider network.

Notes connect in several different ways

Links can connect notes in all kinds of directions. Niklas Luhmann emphasised this possibility of referral [Verweisungsmöglichkeiten]:

“When there are multiple options you can solve the problem by placing the note wherever you want and create references to capture other possible contexts.” - Luhmann, Communication with Zettelkasten

Consider too Daniel Lüdecke’s presentation on Zettelkasten structure PDF. This clearly shows what Luhmann did and didn’t do (according to Lüdecke at least - see especially slide 31 or thereabouts).

Avoid premature closure

A finished piece of work such as a book or article is fixed. Its structure is basically final. This is not true of your notes. They are still fluid, still open to shuffling and re-shuffling. The Zettelkasten’s adaptive structure is confirmed by Schmidt’s summary:

“At first glance, Luhmann’s organization of his collection appears to lack any clear order; it even seems chaotic. However, this was a deliberate choice. It was Luhmann’s intention to “avoid premature systematization and closure and maintain openness toward the future”. A prerequisite for a creative filing system, Luhmann noted, is “avoiding a fixed system of order”. He pinpoints the disadvantages that come with one of the common systems of organizing content in the following words: “Defining a system of contents (resembling a book’s table of contents) would imply committing to a specific sequence once and for all (for decades to come!)”. His way of organizing the collection, by contrast, allows for it to continuously adapt to the evolution of his thinking.” - Johannes F.K. Schmidt. ‘Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine’, in Cevolini, Alberto.; Forgetting Machines : Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe. Brill, 2016. Ch. 12, p. 300. PDF

A disclaimer

Your mileage may vary. When turning your note-work into a network, do what works for you, not what worked for a dead German sociologist.

See also:

Walter Benjamin on the obsolete book

“Already today, as the current scientific mode of production teaches, the book is already an obsolete mediation between two different card file systems. For everything essential is found in the index box of the researcher who wrote it, and the scholar who studies it assimilates it in his own card file.”

“Und heute schon ist das Buch, wie die aktuelle wissenschaftliche Produktionsweise lehrt, eine veraltete Vermittlung zwischen zwei verschiedenen Kartotheksystemen. Denn alles Wesentliche findet sich im Zettelkasten des Forschers, der’s verfaßte, und der Gelehrte, der darin studiert, assimiliert es seiner eigenen Kartothek."

Walter Benjamin - Attested Auditor of Books, in One Way Street (1928) 💬

Comment

Was the book really already obsolete in 1928, as the German cultural theorist Walter Benjamin claimed?

If so, it has nevertheless enjoyed a long and distinguished afterlife. And Benjamin’s sly reference to what ‘the current scientific mode of production’ teaches, may suggest a certain irony in his claim.

But the real irony is that the card index was sooner for obsolescence than the book. During the 1980s and accelerating into the 1990s millions of index cards were thrown out, to be replaced with computer databases. Despite a very niche resurgence of interest in the quaint technologies of the ‘Zettelkasten’ (German for ‘index card box’, there’s no real sign of a come-back. The book, meanwhile, has been assailed mightily by the e-book, but as Monty Python fans would say: “It’s just a flesh wound”.

However, another way of viewing this technological transition would be to say that the card index, in the new form of the electronic database, has utterly triumphed. Now everything is just the front-end of a database, including books.

References

Benjamin, W. (2016[1986]) One Way Street, Trans. E. Jephcott. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. P. 43.

Source: www.heise.de/tp/featur…

Cited in Stop Taking Regular Notes; Use a Zettelkasten Instead - Hacker News

See also: Researching Benjamin Researching

Hermann Burger - Serious about a Zettelkasten?

The Swiss writer Hermann Burger (1942–1989) wrote the draft of a novel in 1970 called Lokalbericht (1970) [Local Report].

“‘Local Report’ – I already have the title, the hardest part of a book. Now, I’m just missing the novel.” [“Lokalbericht – den Titel, das Schwierigste an einem Buch, habe ich schon. Fehlt mir nur noch der Roman."]

The story’s narrator was right. Burger was a poet and novelist but he never finished this early novel. He died in 1989 and it wasn’t published until October 2016. I found a single English-language review.

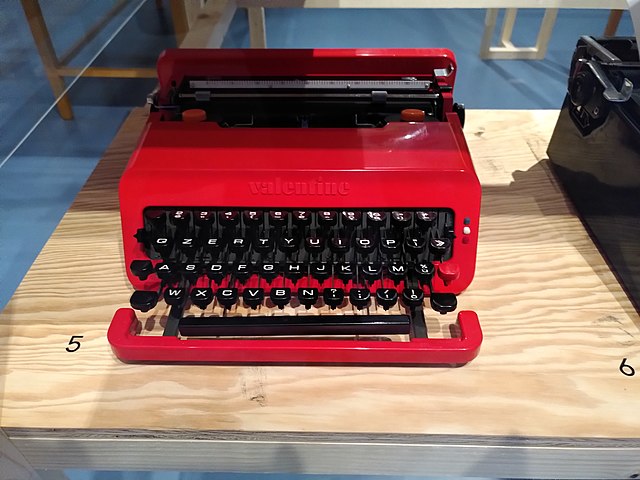

The protagonist of Lokalbericht, the young teacher Günter Frischknecht1 is in the canton of Ticino trying to write two pieces of work at the same time, a dissertation and a novel, writing on two different typewriters and using two different Zettelkästen. These two card indices get mixed up and the slips intermingle. What to do in this situation? Reality and fiction apparently can no longer be distinguished.

This farcical Zettelkasten confusion is foreshadowed early on in the novel by Frishknecht’s academic supervisor Professor Kleinert, of whom he says:

“He didn’t believe I could actually be serious about a Zettelkasten.” [“Dass ich tatsächlich Ernst machen könnte mit einem Zettelkasten, hat er mir wohl kaum zugetraut."]

This story-line seems to be consistent with a long-standing trope among scholars that the loose slips of paper with which they ordered their work could at any moment get mixed up, or even worse, blow away, resulting in chaotic disorder.

Well, now it’s all been put back together. There’s a very impressive interactive online version of the novel, and in 2017 there was an exhibition centred upon it at the Aarau Museum.

It was Manfred Kuhn’s wonderful, though sadly defunct, blog Taking Note Now that originally alerted me to this novel and the Zettelkasten mix-up, but I had completely forgotten.

Thoughts are nest-eggs - Thoreau on writing

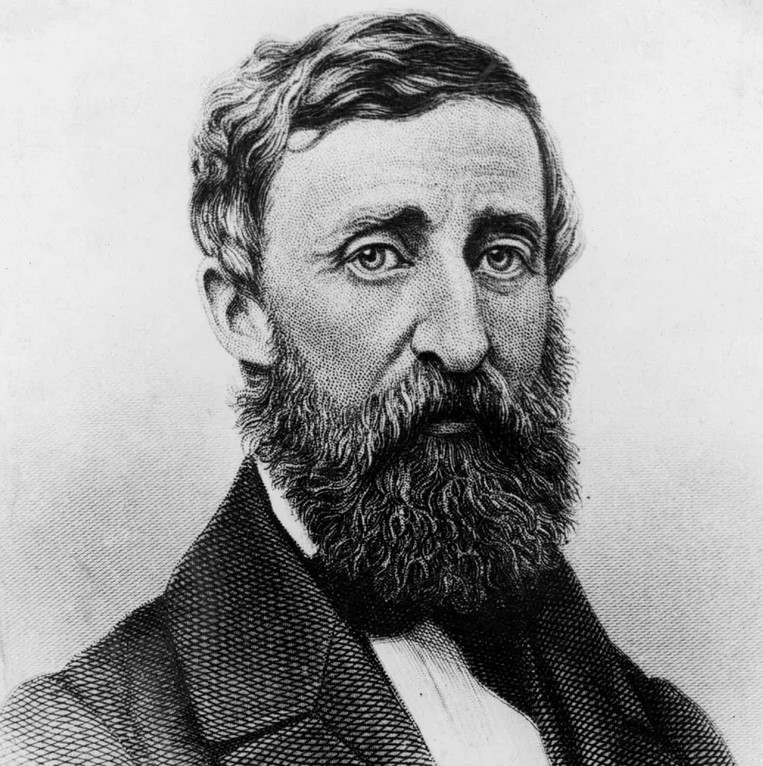

In October 1837 the writer Ralph Waldo Emerson prompted the twenty-year-old Henry David Thoreau to start writing a journal.

“‘What are you doing now?’ he asked. ‘Do you keep a journal?’ So I make my first entry to-day.”

Thoreau finished up with fourteen full notebooks: seven thousand pages, and two million words. Small fragments can add up to an awful lot. From these fragments he constructed pretty much all of his completed works. What began as jottings ended up as mature reflections.

He claimed his disconnected thoughts provoked others, so that ‘thought begat thought’.

Thoreau wrote in his journal:

“To set down such choice experiences that my own writings may inspire me – and at least I may make wholes of parts.

Certainly it is a distinct profession to rescue from oblivion and to fix the sentiments and thoughts which visit all men more or less generally. That the contemplation of the unfinished picture may suggest its harmonious completion. Associate reverently, and as much as you can with your loftiest thoughts. Each thought that is welcomed and recorded is a nest egg – by the side of which more will be laid. Thoughts accidentally thrown together become a frame – in which more may be developed and exhibited. Perhaps this is the main value of a habit of writing – of keeping a journal. That so we remember our best hours – and stimulate ourselves. My thoughts are my company – They have a certain individuality and separate existence – aye personality. Having by chance recorded a few disconnected thoughts and then brought them into juxtaposition – they suggest a whole new field in which it was possible to labor and to think. Thought begat thought.” – Henry David Thoreau, The Journal, January 22, 1852.

The writer, according to Thoreau, doesn’t have a privileged position in relation to ideas or experiences. Everyone has the same access to their “sentiments and thoughts.” But the writer’s special task is to record them.

Thoreau’s meticulous editing process moved from raw field notes, to his journal, to lectures, to essays, and from there to published books. Walden, for example, was published after seven drafts, which took the author nine years to complete.

“The thoughtfulness and quality of his journal writings enabled him to reuse entire passages from it in his lectures and published writings. In his early years, Thoreau would literally cut out pages or excerpts from the journal and paste them onto another page as he created his essays.” - Thoreau’s Writing - The Walden Woods Project

This pretty much sums up the Zettelkasten approach to note-making for me. Thoreau lays out a simple process for “fixing” one’s thoughts in writing and for making something of them.

Note that the thoughts don’t necessarily follow on from one another. The very next idea Thoreau noted in his journal is on a completely different subject: the colour of the winter sun not long before dusk.

Someone who has found their own distinctive approach to writing that seems to echo that of Thoreau is Visakan Veerasamy. He lives in the 21st Century, not the Nineteenth, and instead of a cabin in the woods he probably has a laptop in a cafe. Instead of field notes he writes using tweets and threads, which he then links together in a dense network of thought.

“I’ve basically taught myself to manage my ADHD with notes and threads."- Visakan Veerasamy

What calls Visakan to mind as I reflect on Thoreau’s writing practice is the sense they both seem to share of the seriousness of the practice of making something from nothing by writing short notes in a journal. Visakan says something of which I’m sure both Thoreau and Emerson would have approved:

in a way journaling for yourself is a radical act! It’s an act of self-ownership, self-education. It’s about setting your own curriculum, defining your own worldview, deciding for yourself what is important. I don’t think this should be outsourced to others.

People tend to think of writers like Thoreau as immensely successful. True he became a popular speaker, but Thoreau was not a successful writer, at least not in his lifetime.

“A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers [1849] was initially an abysmal failure. Henry was forced to take back the books that were not sold, totalling 706 out of the 1,000 originally printed. Writing humorously of the event in his journal, he quipped, “I have now a library of nearly nine hundred volumes, over seven hundred of which I wrote myself” (Thoreau 459). Walden [1854], in contrast, was a relatively successful book, though it took most of the rest of Thoreau’s life to sell the 2,000 books of the first edition.” – Thoreau’s Writing - The Walden Woods Project

This knowledge inspires me to write without too much concern for the outcome, and to focus instead on those aspects of the process that lie within my control - recording my thoughts and like Thoreau turning them into nest eggs.

References:

Thoreau, Henry David. 2009. The Journal, 1837-1861. Edited by Damion Searls. New York: New York Review Books.

Image of Thoreau suitable for use on currency

How to be interested in everything

Thomas Edison claimed he was interested in everything

“One day while Mr. Edison and I were calling on Luther Burbank in California, he asked us to register in his guest book. The book had a column for signature, another for home address, another for occupation and a final one entitled ‘Interested in’. Mr. Edison signed in a few quick but unhurried motions… In the final column he wrote without an instant’s hesitation: ‘Everything'”. - Henry Ford on Thomas Edison. Quoted by John Naughton

It’s all very well to believe that everything interests you, but what does that mean in practice?

If you really were interested in everything, how would you get anything done? Each new thing you encountered would surely distract you from your previous interest, and you’d end up surrounded by a heap of unfinished projects. But Thomas Edison, the prolific inventor, had a heap of finished projects - innovative products ready for the market and ready to transform society. More than 1000 US patents were filed under his name, including some of the greatest inventions of all time.

But when nothing prevents you from chasing a new interest, how do you stay focused for long enough to complete the work in front of you?

You need a system

What was Thomas Edison’s system for staying on track? He was clearly very effective, so he must have been able to harness his many diverse interests to produce outcomes. How did he do it? How did he avoid ‘shiny object syndrome’?

Edison recorded everything meticulously. He used notebooks and legers extensively and he encouraged his laboratory workers to do the same. The resulting mountain of notes is a treasure trove for understanding where Edison’s ideas came from and how they developed over time. In their day, these records were mainly used to ensure patents could be registered and defended. Now though, up to five million pages of Edison’s massive work can be studied online through the Edison Project at Rutgers University.

For individuals today, without a team of engineers behind them, but with the amazing advantage of Twenty-first century technology, being interested in everything is a great opportunity, if only we can harness it. Then like Edison, we can happily admit that we’re interested in everything, and put our diverse interests to work.

Publish small fragments to create a larger whole

According to Cory Doctorow, the prolific author and tech activist, blogging (or whatever you want to call it this week) allows you to write simple fragments each day about what interests you today, and to publish it, quite without friction. Over time, Doctorow attests, these small fragments coalesce, and begin to add up to something more substantial.

the traditional relationship between research and writing is reversed. Traditionally, a writer identifies a subject of interest and researches it, then writes about it. In the (my) blogging method, the writer blogs about everything that seems interesting, until a subject gels out of all of those disparate, short pieces.

Blogging isn’t just a way to organize your research — it’s a way to do research for a book or essay or story or speech you don’t even know you want to write yet. It’s a way to discover what your future books and essays and stories and speeches will be about.

Mattias Ott has more to say about this process, and if you read German, there’s even more.

It’s still just up to you

You might well be interested in everything, but the bottleneck all your interests must pass through is you. The measure of your note-taking and writing system is the extent to which it helps you make sense of your diverse interests in a way that communicates meaningfully to yourself and/or to others. Publishing small fragments as you go, which then add up to larger pieces is a way forward that just wasn’t possible in Edison’s day, but is easily available online now to anyone who wants to pursue it.

The lost index cards of Harold Innis

Chris Aldridge has discovered yet another writer who used index cards to construct an extensive body of work from smaller pieces. This practice is often referred to as keeping a Zettelkasten, whether or not the owner was actually German.

The Idea File of Harold Adams Innis (University of Toronto Press, 1980) reproduces an edited version of the typescript Innis, an economic historian, made of his original index cards.

Chris wonders if the index cards themselves might be re-issued for interested readers.

While I appreciate the published book nature of the work, it would be quite something to have it excerpted back down to index card form as a piece of material culture to purchase and play around with. Perhaps something in honor of the coming 75th anniversary of his passing?

I guess such a work might look something like the 138-index-card edition of Nabokov’s unfinished novel, The Original of Laura, which Chip Kidd designed; or his dream diary, constructed from 118 index cards and published with some images of the original notes as Insomniac Dreams.

Sadly, a new edition such as this seems unlikely. That’s because according to the Introduction of the Idea File, Innis himself had around 1,500 of his index cards transcribed to 339 typed and numbered sheets of paper. And the cards themselves were lost, it seems, so I’m not holding my breath. However, it’s always possible that some interpid researcher might investigate the archives1 and discover them hidden away there one day. Stranger things have happened.

“The early history of the material that came to be called the Idea File is obscure. Innis’s son, Donald, recalls that his father used to keep notes on card files, and that there were, at one point, about eighteen inches of white cards, with another five or so inches of white cards containing an index. This index, according to Donald Innis constituted ‘a cross referencing system so that one idea might be referred to under several headings and vice-versa’. These cards appear to have been in manuscript. However, at some point or points, Innis had these notes typed on sheets of paper, and near the end of his life collected the typed notes into one collation which he numbered consequently from 1 to 339.

The cards themselves appear to be lost. It is possible that they still existed at Innis’s death, for there is a second typed version of part of the Idea File. What might have happened is that in the process of preparing Innis’s posthumous material for limited circulation, a typist began working from the cards; then, during the typing, the family discovered the typed version and stopped the retyping.”

I’ve gleaned a few ideas from all this.

First, cross-referencing matters. Innes kept a very extensive index to his cards: 5 inches of index to 18 inches of actual notes. This means his ideas were probably extensively cross-referenced. Makes me think no amount of cross-referencing is too much, if you feel like doing it. But also: don’t get obsessive. Life’s too short to cross-reference everything.

Second, I’m wondering about longevity of work. It really seems like the original notes on index cards were lost. This is such an interesting feature of the resurgence of interest in the working methods of writers and scholars. Is the ‘finished product’ - book or article - really more important and permanent than the supposedly transient and disposable noted from which it was created? And what happens to the ‘Nachlass’ in the age of digitization? Is it both eternal and wipeable at the same time?

Third, the meaning is in the links, but the links are fragile. Given the interlinking of the original notes and their subsequent disappearance, it’s fairly clear that the published ‘idea file’ has lost a significant part of its meaning, since that meaning resides in the links between ideas, not just in the ideas themselves.

Fourth, I noticed that Innis’s notes were often very short. Sometimes just a sentence or two, with compressed, abbreviated syntax. It reminds me of Lichtenberg’s aphorisms, many of which fall slightly flat as prose. Here’s an example. I just wonder what it used to link to:

“University presidents giving each other degrees. A university not an institution designed to that end, or to give members of boards of governers degrees.”

I really appreciate looking into the working practices of writers like this. No doubt there are many more such examples to be found and explored.

I read the top ten Zettelkasten posts on Hacker News so you can do something more wholesome with your day

I really did read a lot of geeky Zettelkasten posts and now I’m going to share them with you

Every so often someone on Hacker News mentions Zettelkasten, a method of making longer work from simple, connected notes. An interesting conversation usually follows. Several of these posts have reached the front page of the Hacker News site, making their authors ‘HN famous’, which is the geek’s version of blowing up on TikTok. The top Zettelkasten post there has around 300 comments, while the 10th has 31.

It’s worth staying a little sceptical about whether visibility on Hacker News is a good proxy for competence. But the comments are usually interesting and often helpful. So here’s a countdown of the top Zettelkasten posts, from 10 to 1. And here, top simply means ‘most commented upon’. For your reference, I’ve noted whether each article is introductory/basic, intermediate/involved, or advanced/complex.

And I’d be interested to know what your favourite Zettelkasten article or resource is - there are a lot to choose from. Or else feel free to tell me exactly why you think this is all a daft waste of time.

So now…

The Zettelkasten article top ten countdown

10. Zettelkasten, linking your thinking, and Nick Milo’s search for ground

Bob Doto, presents a constructive comparison of two different approaches to note-making. The Zettelkasten method, and Nick Milo’s ‘Linking Your Thinking’ (LYT) may appear similar, but as this article points out, they’re really quite different:

“The things that differentiate zettelkasten from LYT are the very things that make each system truly work.”

Bob has some additional articles about the Zettelkasten approach, which are highly recommend.

Complex

Principles

Comparison

9. Org-roam-UI – graphical front end for exploring your org-roam Zettelkasten

Org-Roam is a plain text knowledge management system based on Emacs Org-mode. This post provides an add-on visual interface that shows a map of your notes, similar to other tools such as Roam, Obsidian and Logseq. The tool is “a frontend for exploring and interacting with your org-roam notes.” If you use Org-mode and think you might need this, read on.

Complex

Tools

Github Repo

8. The Zettelkasten Method (2019)

Abram Demski of lesswrong.com goes to town on explaining the evolution of his paper-based Zettelkasten system. He uses 3x5 inch index cards, but he also tried Workflowy and has nice things to say about it. There’s a follow-up at the end, in which the author says he now uses notebooks, but still finds the Zettelkasten referencing system very useful. Along the way he offers one of my favourite principles: “small pieces of paper are just modular large pieces of paper”. This particular article also one of Abram’s top posts on lesswrong.com

Complex

Manual

Principles

Tools

Examples

(Yes, this article covers a lot)

7. My Second Brain – Zettelkasten

Web developer Scott Spence writes about the tools he has been using for notetaking: GitHub, Notion, RoamResearch, Obsidian, Foam. There’s a helpful warning at the top of the article that since it’s three years old the technical details may be out of date. This post is for lovers of digital tools!

Involved

Tools

6. Luhmann’s Zettelkasten

An article from a small German software company about Niklas Luhmann and the structure of his notes. Warning: the description here of how Luhmann connected notes through consecutive numbering (Folgezettel) seems a little simplistic. And TBH I’m not sure how useful this article really is, but the authors do seem to have succeeded with the HN popularity contest.

Basic

Article

5. Introduction to the Zettelkasten Method

A very full introduction to the Zettelkasten method, by Sascha Fast of zettelkasten.de. It’s a great introduction, which also goes into useful depth. If you’ve already been building your Zettelkasten for a while, it’s worth coming back to this to see what you can pick up now you’ve got a real example to play with. These guys also have an app (the Archive) and a great forum, but if you’re reading this you probably already know that.

Involved

Manual

Examples

4. Zettelkästen?

Brian Kam (of Interintellect) writes a simple summary of the Zettelkasten approach, with a follow-up post two years later, by which time he was no longer a beginner since he’d written (drum roll…) 6,837 notes. He implements his Zettelkasten with a Git-based wiki.

Basic

Principles

3. A tour to my Zettelkasten note clusters

Involved

Example

Tech writer Mingyang Li describes his Zettelkasten categories in Obsidian. There are categories like ‘Journal’, ‘chat with people’ and ‘distinguishing-between’. It’s quite useful to see how one person benefits from specific clusters of notes.

2. Zettelkasten note-taking in 10 minutes

Basic

How-to

GitLab software engineer Tomas Vik runs through the slip-box method, based on Sönke Ahrens’s book, How to Take Smart Notes. He recommends creating individual plain text (markdown) files and gives clear examples of how this is structured. He used Zettlr as his markdown-enabled text editor of choice, but mentions alternative apps that do similar things. As a bonus, there’s a follow-up post a year later, in which the author describes how his process has changed (not much) and why he now uses Logseq instead of Zettlr.

1. Stop Taking Regular Notes; Use a Zettelkasten Instead

Basic

How-to

Amazon data scientist Eugene Yan wins the HN Zettelkasten popularity prize with his post on how he implements the system in Roam. Well, it has attracted the most comments anyway. It’s a useful introduction, and commenters mention other apps such as TiddlyWiki, Obsidian and Workflowy. The author seems to have moved on, and started using Obsidian in 2023.

Reflections

Well done If you’ve read this far you are clearly my kind of person. Though you’ve probably noticed that these aren’t necessarily the very best articles about the Zettelkasten method. In any case, everyone differs on what that would even mean. But if you want to gain an understanding of this particular approach to note-making and writing, most of these articles are well worth reading. And if this was all you had available you’d certainly be able to make a good start.

I was interested to discover that quite a few technically-competent people are interested in the Zettelkasten, and are even using one, and was mildly amused to see how keen some seem to be on their many and various digital tools.

I found the follow-up posts, where they existed, the most useful, because they showed how the authors' methods had evolved over time, with actual Zettelkasten use. This is much better than the kind of breathless article that says, basically: “I heard about this Zettelkasten word two days ago and now I’m up against a deadline to post something, anything.” The HN comments are worth skimming too, not least because there are a some sensible criticisms of this system and plenty of alternative suggestions.

To be honest, though, I’ve found the commentary on Reddit and at the zettelkasten.de forum to be generally of a higher quality. This is probably because the participants there are all already Zettelkasten-curious.

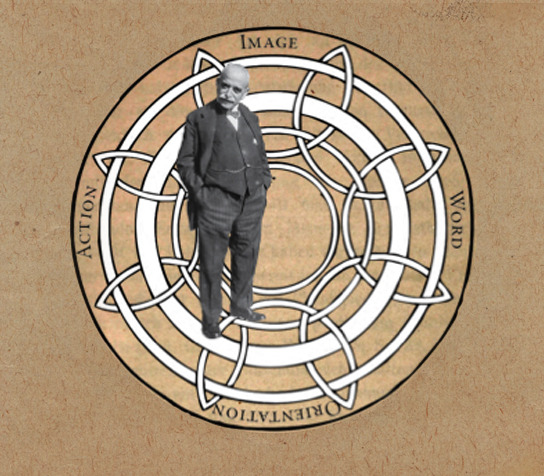

Aby Warburg's Zettelkasten and the search for interconnection

Aby Warburg and the compulsion to interconnect

Aby Warburg was a German art historian obsessed with the connections he saw across European and Mediterranean culture in the afterlife of Antiquity. He even coined a phrase: Verknüpfungszwang - the compulsion to find connections.

“Coining a word that is as fitting as it is symptomatic of the urge it describes, [Aby] Warburg spoke of his Verknüpfungszwang. This ‘compulsion to interconnect’ lies not only at the root of his research and working methods. It is also manifested in regular references within his work to events in his private life, his family and collaborators.” - The Warburg Institute

Three projects in particular display Warburg’s extraordinary scholarly methods.

“The library, panels and boxes formed the ensemble of supports on which Aby Warburg’s spiritual work and intellectual creativity were based.” - Benjamin Steiner, Aby Warburgs Zettelkasten Nr. 2 “Geschichtsauffassung”, In: Heike Gfrereis / Ellen Strittmatter (Hrsg.): Zettelkästen. Maschinen der Phantasie (Marbacher Kataloge, 66). Marbach 2013, S. 154-161.

Taken together, these three amount to a technology for exploring Warburg’s obsession with interconnection.

Image source: Helix Center Warburg Symposium

The Zettelkasten as a thread through the labyrinth of thought

The first technology of note is Warburg’s Zettelkasten, his collection of index boxes, containing notes on many subjects.

“Aby Warburg’s collection of index cards (III.2.1.ZK), containing notes, bibliographical references, printed material and letters, was compiled throughout the scholar’s life. Ninety-six boxes survive, each containing between 200 and 800 individually numbered index cards. Cardboard dividers and envelopes group these index cards into thematic sections. The online catalogue reproduces the structure of the dividers and sub-dividers with their original titles in German and consists of about 3,200 items.” - Warburg Institute Archive

“…Warburg apparently worked constantly with these boxes, and, as his first biographer Carl Georg Heise has reported, he often stood with a strained facial expression bent over the mass of papers and arranged and shifted the individual cards in a long-lasting and never-ending process of order. “Those who follow Warburg’s note box follow his train of thought; from the banking system in Florence, the medieval trading company, the development of individuality, the restless professional work of the Calvinists and the Reformed form of asceticism, to Warburg’s own origin from the old Jewish banking family. The slip box is Warburg’s Ariadne’s thread through his labyrinthine library like his labyrinthine thinking: from the werewolf to the historical concept. A thought, an idea or a new concept does not emerge in a linear progression, but in a process of reciprocating units of ideas and cross-references, which continues until new intersections and nodes have formed.” - Benjamin Steiner, Aby Warburgs Zettelkasten Nr. 2 “Geschichtsauffassung”, In: Heike Gfrereis / Ellen Strittmatter (Hrsg.): Zettelkästen. Maschinen der Phantasie (Marbacher Kataloge, 66). Marbach 2013, S. 154-161.

According to Fritz Saxl, Warburg’s assistant and collaborator, “this vast card-index had a special quality… they had become part of his system and scholarly existence”.

“Often one saw Warburg standing tired and distressed bent over his boxes with a packet of index cards, trying to find for each one the best place within the system; it looked like a waste of energy. […] It took some time to realise that his aim was not bibliographical. This was his method of defining the limits and contents of his scholarly world and the experience gained here became decisive in selecting books for the Library.” - Fritz Saxl, The History of Warburg’s Library (1943-44, p. 329), quoted in Mnemonics, Mneme And Mnemosyne. Aby Warburg’s Theory Of Memory, Claudia Wedepohl (p.389).

A library of good neighbours

Second of note, and much larger than the card-index, is Warburg’s library. As the oldest son, Aby Warburg was in line to inherit his family’s seriously wealthy banking business. But his lack of interest in finance led him to offer the business to his younger brother Max, on the condition he could purchase any books he needed for his research into his true interest, art history. It may have seemed like a modest request, but Warburg’s book collection grew ever larger and eventually expanded into a significant research library. This library was organised like no other. The shelves, and eventually whole rooms were arranged to enable serendipitous connections across and between categories.