What I've learned from non-linear narratives

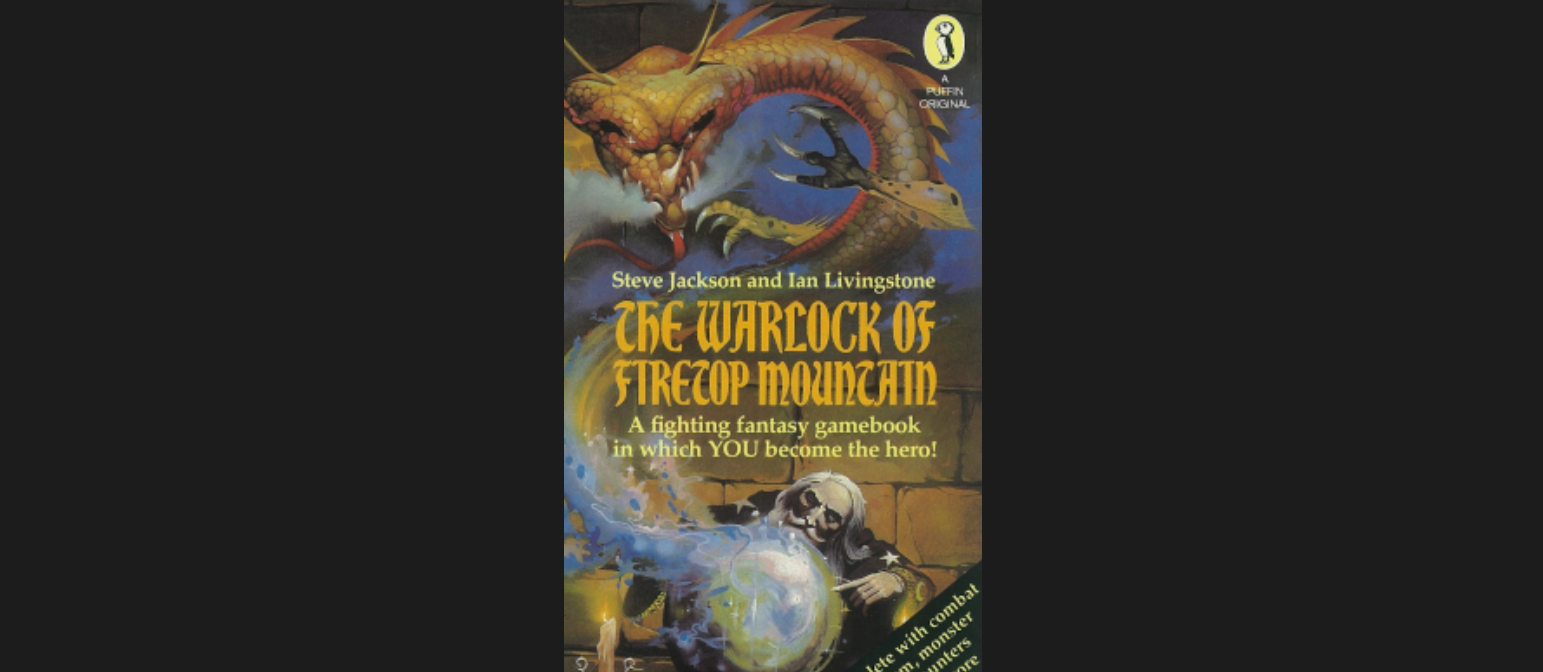

I’m a sucker for non-linear narratives. You might argue this is due to my formative education at exactly the time postmodernist authors such as Italo Calvino were cooking up new forms of literature in which the straight path through the plot was deconstructed and turned on its head. Well, maybe. But truthfully a more formative influence for a teenage boy was the ‘Fighting Fantasy’ series of books starting with The Warlock of Firetop Mountain, which came out in 1982, the year I turned fourteen. Depending on which course of action the reader as protagonist chose, the next page wasn’t the next page at all. You would flip forwards and backwards to seemingly arbitrary page numbers, charting a unique course through the game-like story.

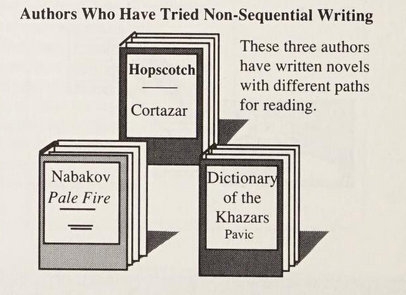

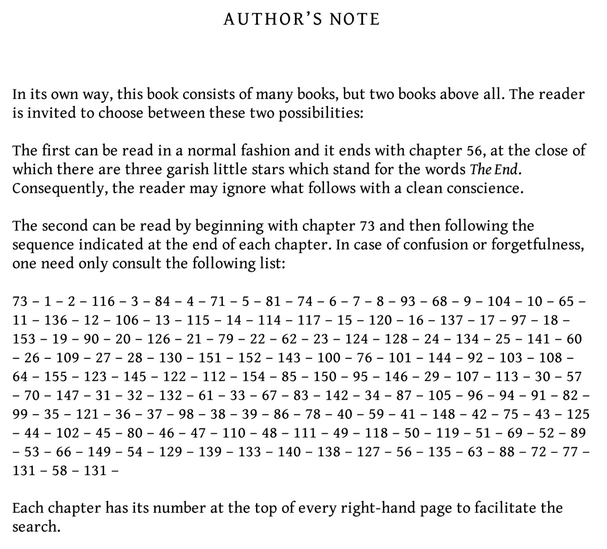

So as my reading tastes matured, I wasn’t at all awed by such texts as Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire, where the commentary and footnotes are as important as the long poem that forms the main text itself. I didn’t balk at Cortazar’s Hopscotch, where there are at least three different paths through a story that bounces between ‘this side’ and ‘the other side’, Argentina and Paris.

And I wasn’t concerned that Milorad Pavić’s Dictionary of the Khazars seems to have no plot and looks a lot like a series of encyclopaedia entries. As Pavić said of it:

“each reader will put together the book for himself [sic], as in a game of dominoes or cards, and, as with a mirror, he will get out of this dictionary as much as he puts into it”.

(Image source: Robert E. Horne, Mapping Hypertext (1989). Archive.)

Then there was Raymond Queneau’s hypertext A Story as you Like It, which allowed the reader to express a preference after almost every sentence. (Source).

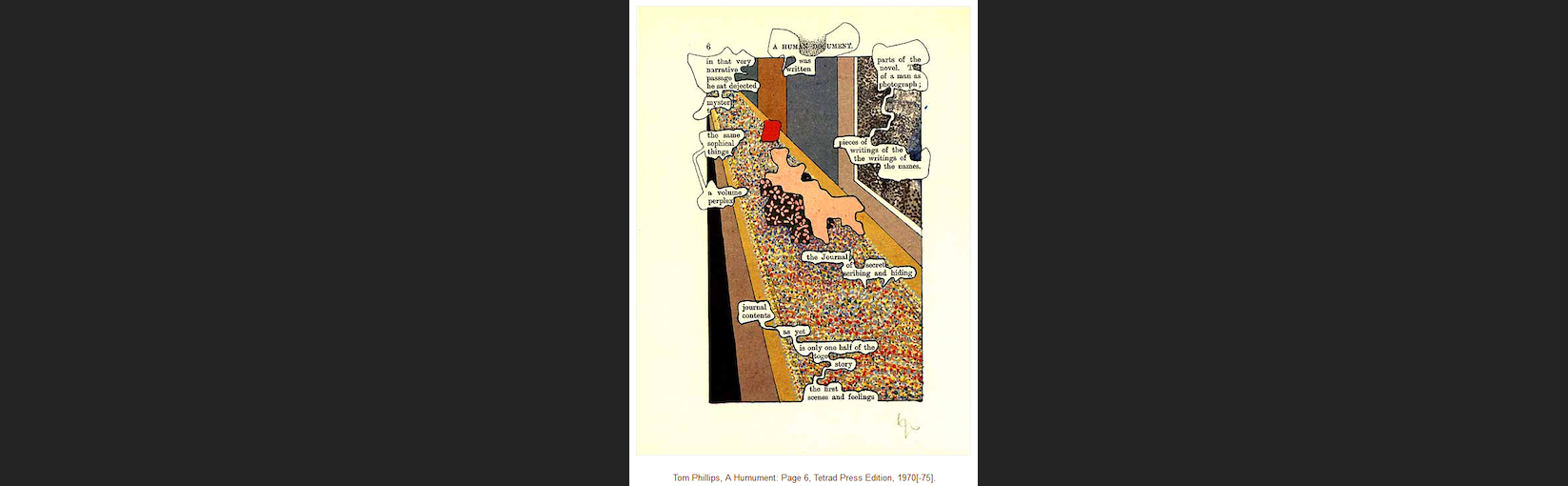

And Tom Phillips’s ‘treated Victorian novel’ A Humument didn’t upset me either. Instead I found it both puzzling and enchanting.

(Image source: humument.com )

There are plenty more such novels, and I’ve enjoyed all those I’ve read. Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller remains one of my very favourite novels, and showed me what it was possible for a novel to be.

The only one of these oblique narratives I’ve found truly daunting is Finnegans Wake by James Joyce. Since the famously dense novel ends mid-sentence, and since that sentence is the start of the book’s first sentence, it feels eerily as though I’m still reading it.

What I’ve learned from all these narratives is that there’s a left-field way of thinking about the world that doesn’t follow the straight path. The route forward doesn’t have to lead in one true direction but potentially many. And my reading makes me want to pay my respects to the potentiality inherent in the multiplicity of avenues in front of me in real life.

These narratives point not only to different ways of telling stories, often uncomfortable but always intriguing, but also to different ways of learning. As the collection of essays, New Directions In Rhizomatic Learning (2023) suggests,

“Knowledge transfer is no longer a fixed process. Rhizomatic learning posits that learning is a continuous, dynamic process, making connections, using multiple paths, without beginnings, and ending in a nomadic style.”

- New Directions in Rhizomatic Learning: From Poststructural Thinking to Nomadic Pedagogy. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2023.

But how does all this relate to my own writing practice, I hear you ask.

Well this multiplicity of possible ways forward is one of the great strengths of my habit of making atomic, linked notes. My network of notes is a rhizome not a tree.

With my atomic, linked notes, I’m not constrained to follow a single line of thought. Like those Fighting Fantasy books of my youth or Pavić’s dictionary, my notes allow me to jump between ideas and create new paths through existing knowledge. Each time I review my collection, I discover different routes and unexpected insights—just as each reader of Dictionary of the Khazars constructs their own unique experience.

This rhizomatic approach to knowledge isn’t just a quirk of my reading preferences or a holdover from teenage adventures in Firetop Mountain. It’s a fundamental way of engaging with the world—acknowledging that meaning spreads like mycelial roots in all dimensions rather than flowing in one direction. My notes aren’t just for information storage; they’re a little bit like a living organism where ideas connect and transform in patterns I couldn’t have predicted when first writing them. True, they’re not alive, but they are a little lively.

One of the greatest benefits of this approach is that I never need to decide early on what the final structure will be. Unlike the standard writing process—where you select a subject, create an outline, and then struggle to fill it—my work grows organically. The structure emerges gradually through connections rather than being imposed from the beginning. I can explore multiple narrative routes before making final decisions about arrangement.

Writing this way is far more enjoyable than the old way. Since I’m only ever focusing on one note at a time, the process feels effortless in comparison. Writer’s block doesn’t really happen. Rather than labouring to assemble my thoughts according to some predetermined plan, I watch my work grow almost autonomously through connections that reveal themselves. It’s a little bit like completing a jigsaw puzzle without being bound by the picture on the box—I can arrange the pieces how I like to create something I never knew was possible.

OK, so maybe this merely explains my impatience with jigsaw puzzles. I admit it’s not a perfect analogy.

That said, perhaps this is why I’ve always been drawn to those experimental narratives—they weren’t breaking rules so much as revealing that the straight line was only ever one possibility. Faced with potentially infinite branching paths, I find that the most interesting stories emerge from the bottom up, when I wander away from the planned route to create unexpected alternatives. I didn’t know what I was writing about when I started making the notes that eventually formed this little reflection. But now I do.

Please subscribe to the Writing Slowly weekly email digest. There’s not much in it because I’m still writing slowly. But hey, free email!