How to write a better note without melting your brain

There’s a great line in Bob Doto’s book A System for Writing which goes like this:

“The note you just took has yet to realize its potential.”

Haven’t you ever looked at your notes and had the same thought? So much potential… yet so little actual 🫠.

Perhaps you jotted something down a couple of days or weeks ago and returning to it now you can’t remember what you meant to say, or what you were thinking of at the time.

Or perhaps you made a great note then, but now you can’t find it.

Or maybe you just know your note connects to another great thought… but you can’t for the life of you remember what.

Well I already make plenty of half-baked notes like these, but how can I make them better? It’s not something they teach in school, so most of us don’t even realize there’s untapped potential, if only we could access it.

So, how can I make worthwhile notes from my almost illegible scribbles on the fly? Well, here’s what works for me. Maybe it’ll work for you too.

When writing my notes, I just have a few simple rules that I mostly stick to:

- 📄 Plain text (Markdown) notes.

- 💡 Each note is a single idea with a unique ID.

- 🪄 Each note deserves a clear title.

- 🔗 Notes link meaningfully to other notes.

Each of these points is a learnable mini-skill in its own right, but none of them is complicated1. And I don’t start from there. Often I really am just scribbling anything that comes to mind. But inspired by Bob’s note mantra, and in search of my note’s hidden potential, I get right to work.

It’s not much of a note, but it’s my own.

Here’s how I take a ‘bad’ or very basic fleeting note, and turn it into a serviceable main (or permanent) note2:

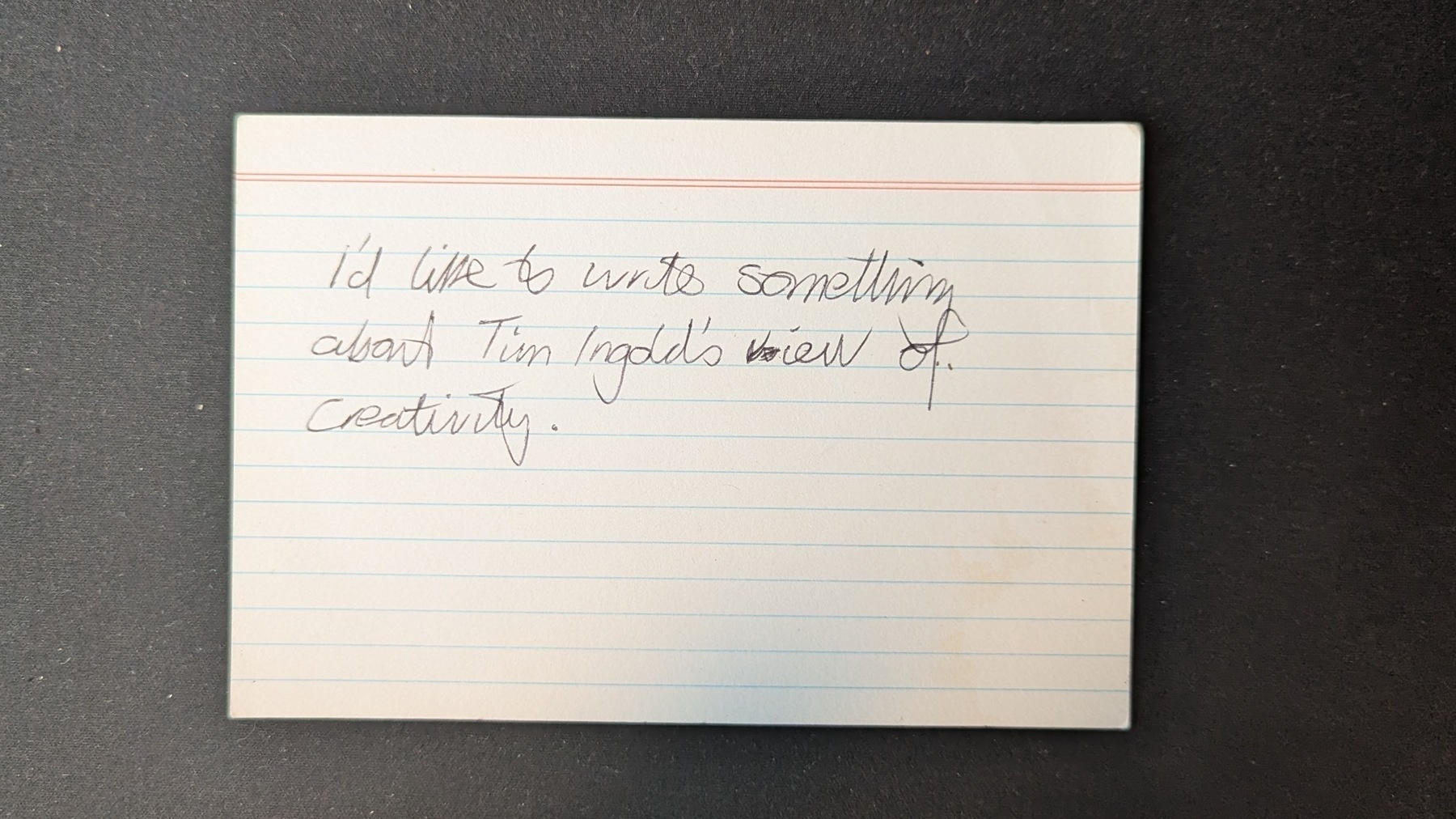

- Start with a quick and dirty note, however rough. I might write it on a card. I might write it on my shoe:

"I'd like to write something about Tim Ingold's view of creativity".

OK, it may not be much of a note, but at least it's something to start with.

- Next, if there’s a reference, make sure I’ve captured it:

"I'd like to write something about Tim Ingold's view of creativity. See: Ingold, Tim, 'The textility of making'. Cambridge Journal of Economics 2010, 34, 91–102 doi:10.1093/cje/bep042 pdf."

- Now add a tiny bit of context, so my future self might understand the value I’m seeing right now but no doubt will soon forget:

"I'd like to write something about anthropologist Tim Ingold's view of creativity. He contrasts textilic modes of creation (i.e. weaving) with architectonic modes (i.e. architecture). The latter requires aiming for an ideal outcome, whereas the former entails going where the materials take you, going with the flow. In fact, creativity is more about flow than stasis, more about 'itineration' (wayfaring) than iteration (making an object), he says.

Reference: Ingold, Tim, 'The textility of making'. Cambridge Journal of Economics 2010, 34, 91–102 doi:10.1093/cje/bep042 pdf."

-

Also add at least one link. This note might link to another one called ‘Creativity involves flow’. And it’s inviting me to start another one entitled “Writing ideas”, so I’ll add that.

-

Finally, create a strong declarative title and an ID: “202411042258 Creativity involves weaving and wayfaring” So now I have an excellent note3 and it looks a bit like this:

202411042258 Creativity involves weaving and wayfaring

I'd like to write a little article about anthropologist Tim Ingold's view of creativity. He contrasts textilic modes of creation (i.e. weaving?) with architectonic modes (i.e. architecture?). The latter requires aiming for an ideal outcome, whereas the former entails going where the materials take you, going with the flow. In fact, creativity is more about flow than stasis, more about the process than the blueprint, and more about 'itineration' (wayfaring) than iteration (making an object), he says.

Links:

202411042250 Creativity involves flow.

202411042306 Writing ideas.

Reference:

Ingold, Tim, 'The textility of making'. Cambridge Journal of Economics 2010, 34, 91–102 doi:10.1093/cje/bep042 pdf.

Now my note is more useful than the original fleeting note that started it, because:

- it’s a single idea (i.e. it makes a point);

- it has a clear title; - I can find it again;

- it links to my existing ideas; and

- it has already spawned an additional new note.

True, this was a bit of work, but it will be worth it to be able to return to this note and make something else from it. It’s a repeatable process based on my four simple rules. This basic process for writing valuable and enduring notes has helped me gain clarity, focus and momentum, without getting overwhelmed by a fancy system. I hope it helps you.

I recommend just getting started and learning as you go, but if you want more detail:

- read Bob Doto’s great book, A System for Writing, or

- watch Morgan’s helpful video, How to take notes that actually help you think and write.

- more from me on a minimal approach to writing notes.

I’d like to hear how you already make effective notes, so please let me know on micro.blog, Mastodon or Bluesky.

This article is based on a comment I made on the Zettelkasten subreddit.

Subscribe to a weekly email round-up of this site:

-

I’ve probably written something about each on my site, try the built-in search if you’re interested. ↩︎

-

These names are flexible. The point is, you start with a scrappy note and end with a serviceable note. ↩︎

-

Yes, I’m big-noting myself, as we say in Australia. ↩︎