A minimal approach to making notes

I want a minimal approach to making notes.

I don’t want anything fancy, just enough structure to be useful.

When I see people’s souped-up Obsidian note-taking vaults my head spins (OK, I’m jealous). I also wonder, though, what extra result is achieved with a fantastically complex system. Having said that, I’m keen on people creating a working environment that works for them, and I do admire people’s creativity in this area.

I just can’t be bothered to do it myself.

When discussing the Zettelkasten approach to making notes, it seems there are a lot of different note types to consider, which confuses people. The extensive discussion about different types of notes caused by reading Sonke Ahrens’s book How to Take Smart Notes makes me think this multiple-note-types approach is just too complicated for me. So what do I do instead?

I prefer to look directly at what sociologist Niklas Luhmann did with his Zettelkasten (and the associated research project on it.

I’ve also found inspiration in Dan Alloso’s book, How to Make Notes and Write. This is what Anna Havron said about it at Analogue Office

“I found Dan Allosso’s zettelkasten system to be cleaner and simpler than anything else I’ve read. He does not parse out four or five fine-grained types of notes (fleeting, literature, evergreen, sprout, etc). He uses two: source notes, and point notes. “Source Notes” are notes he makes mostly from the source but with some initial thoughts and questions. “Point Notes” are his own thoughts: “Others have called these “Main Notes” or “Permanent Notes” or “Evergreen Notes”. I called them Point Notes to remind myself that when I write them I should be making a point.” (Allosso 2022, p 66)”

- Allosso, Dan; Allosso, S.F.(2022) How to Make Notes and Write. Kindle Edition.

He’s not the only person claiming there’s only two kinds of notes. Bob Doto says of Sonke Ahrens’s book (p.23-24):

“the author refers to two categories of notes1 permanently stored in the slip-box: “the main notes” and “literature notes.””

What I get from all this is that there are really only two kinds of note worth thinking about and putting in your Zettelkasten, at least when you start out. Yes, only two, and here they are:

-

The note you write to make sure you record the source of information. This is a source note (also known as a literature note or a reference note or a bibliographic note). As Bob Doto says: it’s “a single note containing references to all the interesting passages in a book (or other piece of media) that you encounter.”

-

The note you write to make some kind of point, whatever it is. Ideally, this will be either a concept or a proposition, but… you do you. This is a point note (but you can call it a permanaent note, a main note, a Zettel, an evergreen note, or even, confusingly, a literature note, and that’s fine too.)

Now I’m going to show you what these two notes look like. They are quite straightforward.

What does a source note look like?

A source note looks like this (lifted from the excellent article What is a literature note?:

Ahrens, S. (2017). How to Take Smart Notes. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- 13 reference to speed writing (effort)

- 14 trying to squeeze too much (squeeze)

- 15 no effort (effort)

- 18 ref to bibliography (lit note)

- 20 index ref (index)

- 21 need only make a few changes (effort)

- 24 discrepancies btw lit/perm (perm)

You record the bibliographic details of something you’re reading (or viewing or listening to), and you briefly note interesting ideas, with their page number.

When you want to expand one of these ideas, you link the line on the source note to a point note that takes the idea further in some way.

What does a point note look like?

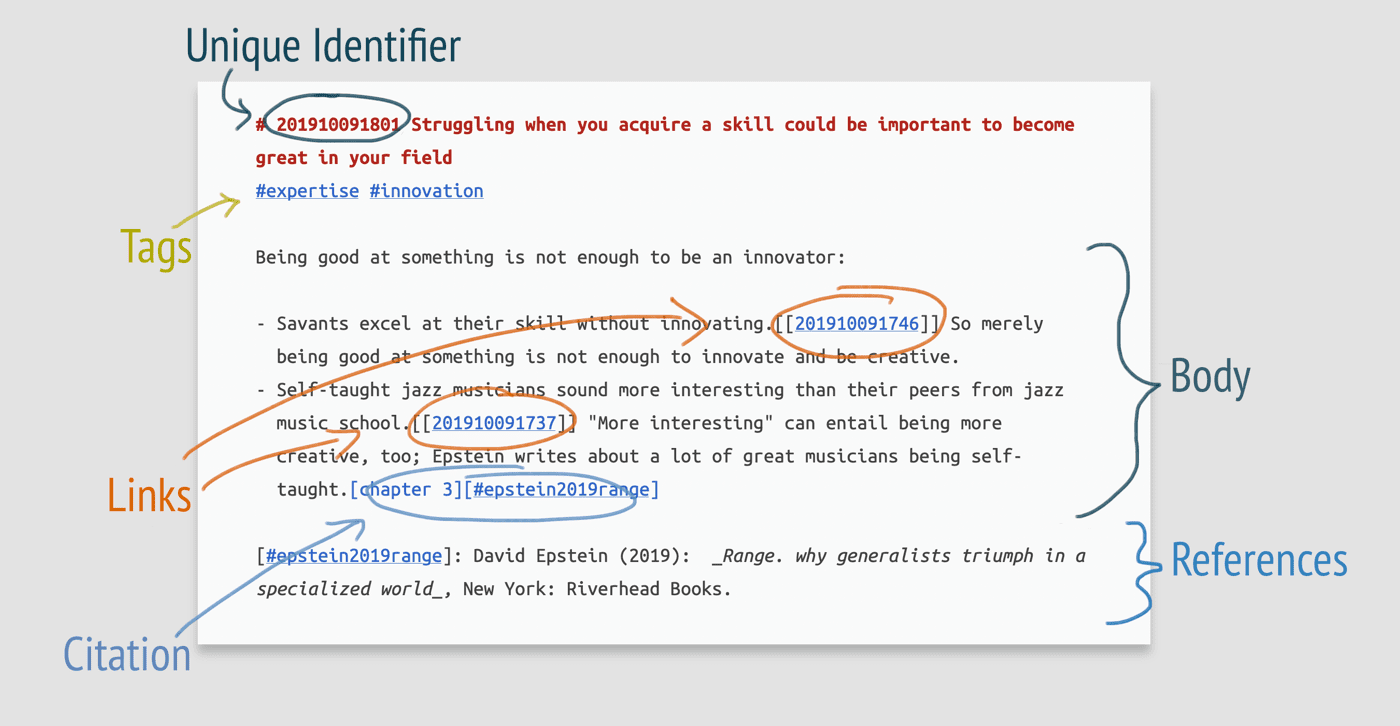

A note looks like this (from the indispensable article Introduction to the Zettelkasten Method, which you should definitely read):

Sure, a note like this has plenty of metadata such as an ID, a title, some links and maybe some references, but in the body of the note, the author is just making a single point.

So, to recap: you only need two kinds of notes: source notes and point notes (or reference notes and main notes, or literature notes and… look, just call them what you want, OK?).

Bonus tip: There is actually one other type of note that you might want to use once you’ve got your system going, but it’s optional, especially when starting out.

The one further useful kind of note is the hub note (or structure note, or map of content2). You use it to create a bit of structure in your collection of notes. But remember, a network of notes is a rhizome not a tree. You don’t need to impose the structure prematurely - it arises organically from your notes as you write them, not from top-down categories.

What does a hub note look like? It looks like a note title followed by a simple list of other linked note titles and note IDs. It’s almost like a mini- table of contents or an outline for an article. But really, it’s just a point note where the point of the note is: “here’s a list of linked notes that are all related to the title of this note”. What’s helpful about this is that the hubs emerge gradually from your notes as they accumulate, from the bottom up.

That’s it really. Source notes, point notes and hub notes.

That’s all you need to get going (and then to continue). After that you can invent all the note types you like, as and when they suit your particular uses. For example, in the novel Lila, Robert Pirsig’s protagonist Phaedrus writes about ‘program slips’, which describe how his note system works.

“PROGRAM slips were instructions for what to do with the rest of the slips. They kept track of the forest while he was busy thinking about individual trees. With more than ten thousand trees that kept wanting to expand to one hundred thousand, the PROGRAM slips were absolutely necessary to keep from getting lost.”

Well, maybe. Pirsig just made that note type up, as well as a few others, and so can you if you want.

Why not check out my own book, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters? And you can sign up to the weekly email news. There won’t be much, because I’m still writing slowly, but at least you’ll know you didn’t miss it.

Now read:

How to start a Zettelkasten from your existing deep experience

Even the index is just another note

Does the Zettelkasten have a top and a bottom?

Three worthwhile modes of notetaking

How to connect your notes to make them more effective

When it comes to writing notes how much mess is just enough?

-

My emphasis ↩︎

-

See Nick Milo’s Linking your Thinking for detailed information about maps of content ↩︎