article

-

To clarify, I’m claiming, with Solms, that Freud’s pursuit was meta-psychological, not metaphysical. In contrast, I’m going further than Solms and reading Jung against himself here. Jung seems to have taken a strongly metaphysical approach (Mills 2019), whereas, I’m suggesting his programme may nevertheless be treated as a non-metaphysical but meta-psychological enquiry into the relationship between consciousness and human culture, not the brain. Mark Solms took part in a discussion on the differences between Freud and Jung. ↩︎

- First Ashby made almost random notes in his notebooks, which he indexed alphabetically by key-word, using a card index. To aid referencing, he gave the notebooks a continuous page numbering across all 25 volumes.

- Next, in April 1943 and based on his notes, he created an outline for a book manuscript p.1234, then revised it six months later, on October 4th p.1447.

- Satisfied with the revised outline p.1497, he created a completely new card index (the ‘Other’ index), arranged by subject, based on the outline headings, rather than key-words. This new index is what he describes in his note of October 20th 1943, which is reproduced above.

- He deliberately kept this second index flexible, so that his notes could be re-arranged for as long as possible prior to the drafting of the actual manuscript.

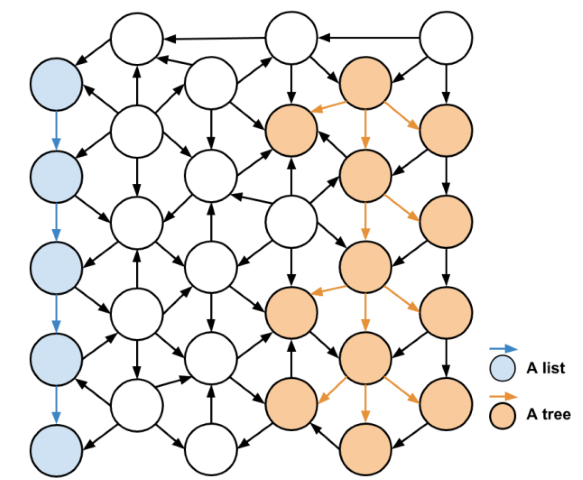

- A network of notes is a rhizome not a tree.

- Manuel Lima on The power of networks (it’s a cool video!)

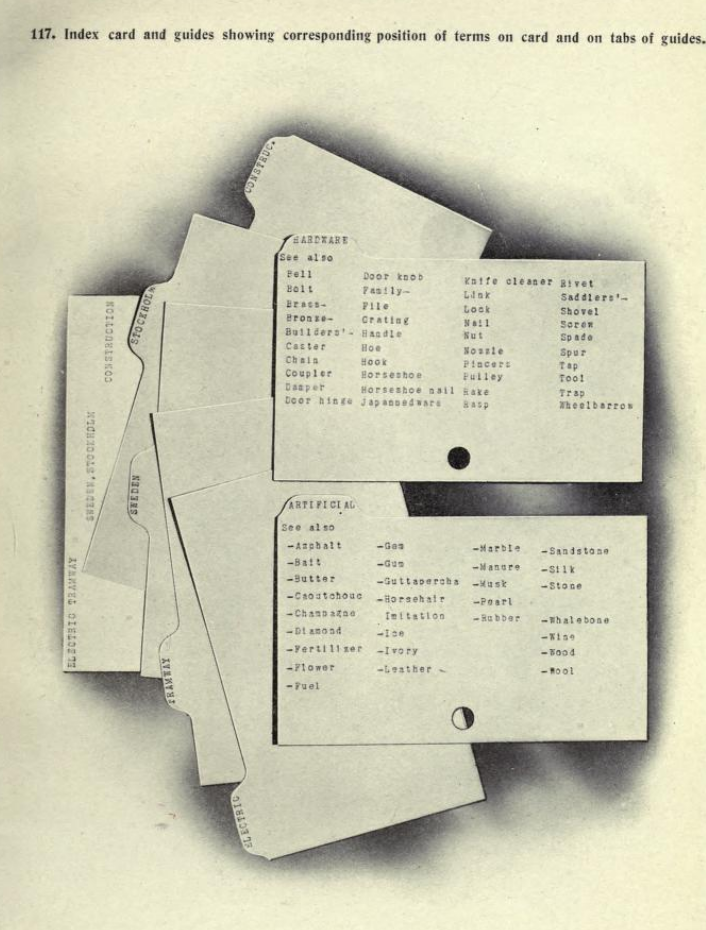

- Top image source: The Card System at the Office by J. Kaiser, 1908.

- Free-form note-making. In this mode, you start with no expectations and just make notes whenever something grabs you. This is great when you don’t yet know what you want to focus on. The risk is you try to read everything, only to discover it’s like drinking the ocean. Ars longa, vita brevis, so you’ll ultimately need to narrow down your field somehow.

- Directed note-making. In this mode, you already know, broadly, what interests you, for example, Richard Hamming’s 10-20 problems. So you make notes whenever something you read resonates with one of your predetermined interests. I used to think I was interested in everything, like Thomas Edison. But after writing notes on whatever took my fancy for a while, I observed that really, I kept revolving around a fairly limited set of concerns. So mostly these days I make directed notes, or else engage in the closely related purposeful note-making.

- Purposeful note-making. This mode is more focused still than directed note-making. Here you have a specific project in mind, such as a particular book or article you want to write, and so you make notes whenever your reading material chimes with what you want to write about. If there’s a risk to this kind of note-making, it’s that in your focused state, you’ll miss ideas that you might otherwise have found worth making notes about.

-

Christian Wiman, “The Preacher Addresses the Seminarians” from Once in the West (Farrar Straus and Giroux, 2014). ↩︎

- Baker, S. (1985). The practical stylist. Harper and Row. p. 2-3). 1

- Choose your own race and finish it

- Only sinners left down here

- Why I’m writing slowly

- You can get a lot done by writing slowly

- My range is me

- The mastery of knowledge is an illusion

-

Quoted in Cruz, Robson Nascimento da Cruz, and Junio Rezende. “A escrita de notas como artesanato intelectual: Niklas Luhmann e a escrita acadêmica como processo.” Pro-Posições 34 (2023): e20210123. English PDF. ↩︎

-

In the case of reading magazine submissions, the threat of AI imitating humans is a little overblown. To maintain a manageable slush pile you simply need to introduce some little task that only a human could perform. You could accept only manuscripts that were sent in the mail, for example. This immediately kills the zero-cost proposition of submitting AI-written stories. And when that gets gamed, you could decide to read only those submissions with a hand-written address on the envelope. In other words, if you only want to accept human labour, you just need to request human labour. Re-introduce any human work at all, and the cost benefits of automation are curtailed or even eliminated. ↩︎

-

If you’re using crumbs to reach the molten heart of creation, they’ll pretty soon be toast. ↩︎

- the friendship roles I’m good at,

- the roles I’m bad at, and

- the roles I’d like to focus more on.

- The Builder

- The Champion

- The Collaborator

- The Companion

- The Connector

- The Energizer

- The Mind Opener

- The Navigator

-

Well, Tom Rath’s 2006 book, Vital Friends. ↩︎

-

an emerging network of federated networks, all interoperable, thereby marginalising the walled garden silos of monopolistic data-extracting megacorps. HT: Paulo Amoroso ↩︎

- global education

- effective language learning

- multilingualism

- equal treatment regardless of language - language rights

- language diversity; and

- human emancipation

- N - what larger pattern does this concept belong to?

- S - what more basic components is this concept made of?

- E - what is this concept similar to?

- W - what is this concept different from?

-

you’ll write worthwhile notes that address your own questions and

-

this hook of curiosity will help you remember as you learn.

-

What does the medium enhance?

-

What does the medium make obsolete?

-

What does the medium retrieve that had been obsolesced earlier?

-

What does the medium reverse or flip into when pushed to extremes?

Can we understand consciousness yet?

Professor Mark Solms, Director of Neuropsychology at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, revives the Freudian view that consciousness is driven by basic physiological motivations such as hunger. Crucially, consciousness is not an evolutionary accident but is motivated. Motivated consciousnesses, he claims, provides evolutionary benefits.

Mark Solms. 2021. The Hidden Spring. A Journey to the Source of Consciousness. London: Profile Books. ISBN: 9781788167628

He claims the physical seat of consciousness is in the brain stem, not the cortex. He further claims that artificial consciousness is not in principle a hard philosophical problem. The artificial construction of a conscious being, that mirrors in some way the biophysical human consciousness, would ‘simply’ require an artificial brain stem of some sort.

I have been wondering what it would be like to have injuries so radical as to destroy the physiological consciousnesses, if such a thing exists, while retaining the ability to speak coherently and to respond to speech. Perhaps a person in this condition would be like the old computer simulation, Eliza, which emulated conversation in a rudimentary fashion by responding with open comments and questions, such as “tell me more”, and by mirroring its human conversation partner. The illusion of consciousness was easily dispelled. The words were there but there was no conscious subject directing them. However, since then language processing has become significantly more advanced and machine learning has progressed the ability of bots without consciousness to have what appears to be a conscious conversation. Yet still there’s a suspicion that there’s something missing.

One area of great advance is the ability of machine learning to take advantage of huge bodies of data, for example, a significant proportion of the text of all the books ever published, or literally billions of phone text messages, or billions of voice phone conversations. It’s possible to program with some sophistication interactions based on precedent: what is the usual kind of response to this kind of question? Unlike Eliza, the repertoire of speech doesn’t need to be predetermined and limited, it can be done on the fly in an open ended manner using AI techniques. But there’s still no experiencer there, and we (just about) recognise this lack. Even if we didn’t know it, and bots already passed among us incognito, they might still lack ‘consciousness’.

So, at what point does the artificial speaker become conscious? If the strictly biophysical view of consciousness is correct, the answer is never.

A chat bot will never “wake up” and recognise itself, because it lacks a brain stem, even an artificial one. Even if to an observer the chat-bot appears fully conscious, at least functionally, this will always be an illusion, because there is no felt experience of what it is like to be a chat bot, phenomenologically.

From the perspective of neo-Freudian neuropsychology, it is easy to see why Freud grew exasperated with Carl Jung. Quite apart from the notorious personality clashes, it seems Jung departed fundamentally from Freud’s desire to relate psychological processes to their physical determinants. For example, what possible biophysical process would be represented by the phrase “collective unconscious” (see Mills 2019)?

For Freud, the consciousness was strongly influenced by the unconscious, which was his term for the more basic drives of the body. For example, the Id was his term for the basic desire for food, for sex, to void, etcetera. This was unconscious because the conscious receives this information as demands from a location beyond itself, which it finds itself mediating.

He saw terms such as the Id, the Ego and the Superego as meta-psychological. He recognised what was not at the time known about the brain, such as the question of where exactly the Id is located, but he denied it was a metaphysical term. In other words, he claimed that the Id was located, physically, somewhere, yet to be discovered. His difficulty was he fully understood that his generation lacked the tools to discover where.

Note that meta-psychology is explicitly not metaphysical. Freud had no more interest in the metaphysical than other scientists of his time, or perhaps ours have done. His terminology was a stopgap measure meant to last only until the tools caught up with the programme.

The programme was always: to describe how the brain derives the mind.

Jung’s approach made a mockery of these aspirations. Surely no programme would ever locate the seat of the collective unconscious?

But perhaps this is a misunderstanding of the conflict between Freud and Jung. What if the distinction is actually between two conflicting views of the location of consciousness? For Freud, and for contemporary psychology, if consciousness is not located physically, either in the brain somewhere or in an artificial analogue of the brain, where could it possibly be located? Merely to ask the question seems to invite a chaos of metaphysical speculation. The proposals will be unfalsifiable, and therefore not scientific - “not even wrong”.

However, just as Mark Solms has proposed a re-evaluation of Freud’s project along biophysical lines, potentially acceptable in principle to materialists and empiricists (i.e. the entire psychological mainstream), perhaps it is possible for a re-evaluation of Jung’s programme along similar lines, but in a radically different direction.

If the brain is not the seat of the conscious, what possibly could be? This question reminds me of the argument in evolutionary biology about game theory. Prior to the development of game theory it was impossible to imagine what kind of mechanism could possibly direct evolution other than the biological. It seemed a non-question. Then along came John Maynard Smith’s application of game theory to ritualised conflict behaviour and altruism, and proved decisively that non-biological factors decisively shape evolutionary change.

What if Jung’s terms could be viewed as being just as meta-psychological as Freud’s, but with an entirely different substantive basis? Lacking the practical tools to investigate, Jung resorted to terms that mediated between the contemporary understanding of the way language (and culture more generally), not biology, constructs consciousness.

What else is “the collective unconscious”, if not an evocative meta-psychological term for the corpus of machine learning?

Perhaps consciousness is just a facility with a representative subset of the whole culture.

I’m wary of over-using the term ‘emergence’. I don’t want to speak of consciousness as an emergent property, not least because every sentence with that word in it still seems to make sense if you substitute the word ‘mysterious’. In other words, ‘emergence’ seems to do no explanatory work at all. It just defers the actual, eventual explanation. Even the so-called technical definitions seem to perform this trick and no more.

However, it’s still worth asking the question, when does consciousness arise? As far as I can understand Mark Solms, the answer is, when there’s a part of the brain that constructs it biophysically, and therefore, perhaps disturbingly, when there’s an analogue machine that reconstructs it, for example, computationally.

My scepticism responds: knowing exactly where consciousness happens is a great advance for sure, but this is still a long way from knowing how consciousness starts. The fundamental origin of consciousness still seems to be shrouded in mystery. And at this point you might as well say it’s an ‘emergent’ property of the brain stem.

For Solms, feeling is the key. Consciousness is the theatre in which discernment between conflicting drives plays out. Let’s say I’m really thirsty but also really tired. I could fetch myself a drink but I’m just too weary to do so. Instead, I fall asleep. What part of me is making these trade-offs between competing biological drives? On Solms’s account, this decision-making is precisely what conscousness is for. If all behaviour was automatic, there would be nothing for consciousness to do.

As Solms claims in a recent paper (2022) on animal sentience, there is a minimal key (functional) criterion for consciousness:

The organism must have the capacity to satisfy its multiple needs – by trial and error – in unpredicted situations (e.g., novel situations), using voluntary behaviour.

The phenomenological feeling of conscioussness, then, might be no more than the process of evaluating the success of such voluntary decision-making in the absence of a pre-determined ‘correct’ choice. He says:

It is difficult to imagine how such behaviour can occur except through subjective modulation of its success or failure within a phenotypic preference distribution. This modulation, it seems to me, just is feeling (from the viewpoint of the organism).

Then there’s the linguistic-cultural approach that I’ve fancifully been calling a kind of neo-Jungianism 1. When does consciousness emerge? The answer seems to be that the culture is conscious, and sufficient participation in its networks is enough for it to arise. If this sounds extremely unlikely (and it certainly does to me), consider two factors that might minimise the task in hand - first that most language is merely transactional and second that most awareness is not conscious.

As in the case of chat bots, much of what passes for consciousness is actually merely the use of transactional language, which is why Eliza was such a hit when it first came out. This transactional language could in principle be dispensed with, and bots could just talk to other bots. What then would be left? What part of linguistic interaction actually requires consciousness? Perhaps the answer is not much. Furthermore, even complex human consciousness spends much of the time on standby. Not only are we asleep for a third of our lives, but even when we’re awake we are often not fully conscious. So much of our lives is effectively automatic or semi automatic.

When we ask what is it like… the answer is often that it’s not really like anything.

The classic example is the feeling of having driven home from work, fully awake, presumably, of the traffic conditions, but with no recollection of the journey. It’s not merely that there’s no memory of the trip, it’s that, slightly disturbingly, there was no real felt experience of the trip to have a memory about. This is disturbing because of the suspicion that perhaps a lot of life is actually no more strongly experienced than this.

These observations don’t remove the task of explaining consciousness, but they do point to the possibility that the eventual explanation may be less dramatic than it might at first appear.

For the linguistic (neo-Jungian??) approach to consciousness the task then is to devise computational interactions sufficiently advanced as to cause integrated pattern recognition and manipulation to become genuinely self aware.

A great advantage of this approach is that it doesn’t matter at all if consciousness never results. Machine learning will still advance fruitfully.

For the biophysical (neo-Freudian) approach, the task is to describe the physical workings of self awareness in the brain stem so as to make its emulation possible in another, presumably computational, medium.

A great advantage of this approach is that even if the physical basis of consciousness is not demystified, neuropsychology will still understand more about the brain stem.

As far as I can see, both of these tasks are monumental, and one or both might fail. However, the way I’ve described them they seem to be converging on the idea that consciousness can in principle be abstracted from the mammalian brain and placed somewhere else, whether physical or virtual, whether derived from the individual brain, analogue or digital, or collective corpus, physical or virtual.

I noticed in the latter part of Professor Solms’s book a kind of impatience for a near future in which the mysteries of consciousness are resolved. I wonder if this is in part the restlessness of an older man who would rather not accept that he might die before seeing at least some of the major scientific breakthroughs that his life’s work has prepared for. Will we work out the nature of consciousness in the next few years, or will this puzzle remain, for a future generation to solve? I certainly hope we have answers soon!.

References:

Mills, J. (2019). The myth of the collective unconscious. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 55(1), 40-53.

Solms, Mark (2022) Truly minimal criteria for animal sentience. Animal Sentience 32(2) DOI: 10.51291/2377-7478.1711

Jules Verne could have told us AI is not a real person

Ross Ashby's other card index

During the Twentieth Century many thinkers used index cards to help them both think and write.

British cyberneticist Ross Ashby kept his notes in 25 journals (a total of 7,189 pages) for which he devised an extensive card index of more than 1,600 cards.

At first it looks as though Ashby used these notebooks to aid the development of his thought, and the card index merely catalogued the contents. But it turns out he used his card index not only to catalogue but also to develop the ideas for a book he was writing.

In a journal entry of 20 October 1943 he explained his decision to switch from an alphabetical key-word index to ‘an index depending on meaning’.

He describes his method as follows:

“20 Oct ‘43 - Having seen how well the index of p.1448 works, & how well everything drops into its natural place, I am no longer keeping the card index which I have kept almost since the beginning. The index was most useful in the days when I was just amassing scraps & when nothing fitted or joined on to anything else; but now that all the points form a closely knit & jointed structure, an index depending on meaning is more natural than one depending on the alphabet. So I have changed to a (card) index with the points of p.1448 in order. Thus it can grow, & be rearranged, on the basis of meaning. Summary: Reasons for changing the form of the index.” - Ross Ashby, Journal, Vol. 7

What was he up to? Thanks to Ashby’s meticulous note-taking, and the fact that it has all been saved and digitized, you can trace his working methods. It also helps that his handwriting is very clear!

This workflow is quite different from that of sociologist Niklas Luhmann, who unlike Ashby, didn’t use notebooks to any great extent. In fact it highlights a particularly striking aspect of Luhmann’s approach: for Luhmann the card index is its own contents; they are one and the same. Put another way, Luhmann’s Zettelkasten is largely self-indexing.

Ashby didn’t do this. Instead he followed the more standard card index system, elaborated, for example, by R.B. Byles, in 1911. In this system, originally designed for business, all documents are filed away, typically in order of receipt or creation, and then accessed by means of a separate card index, which provides the key to the entire collection. Ashby’s innovation was to adapt the card index system to refer to key-words in his notebooks, referenced by page number. Luhmann, certainly, also used key-words. His first Zettelkasten had “a keyword index with roughly 1,250 entries”, while his second, larger Zettelkasten had “a keyword index with 3,200 entries, as well as a short (and incomplete) index of persons containing 300 names” (Schmidt, 2016: 292).

However, due to Luhmann’s meticulous cross-referencing of individual cards, the key-word index isn’t strictly essential to connect the ideas in the Zettelkasten in a meaningful way; Luhmann’s cards link directly to other cards.

Fast-forward two generations and it seems that in the Internet age it is Luhmann’s method that has won out. The online version of Ross Ashby’s journal includes both the notebooks and the index as a single hyperlinked body of work. This represents a tremendous effort on the part of those who have painstakingly digitized the collection. Today, like Luhmann’s Zettelkasten, Ashby’s notebooks, at least in their Web-based incarnation, are finally self-indexing.

And there’s another sense in which Luhmann’s method won out. While Luhmann published scores of books, Ashby published plenty of academic articles, but only two full-length books. And neither of these books, as far as is evident, bear much relation to the manuscript outlines in his ‘other’ index. We can only speculate on whether Ashby might have produced more books had he used a system more like Luhmann’s.

Yet despite their differences, Ashby’s approach in creating his ‘other’ index is very consistent with Luhmann’s concern to keep the order of notes as flexible as possible for as long as possible.

References

The W. Ross Ashby Digital Archive

Jill Ashby (2009) W. Ross Ashby: a biographical essay, International Journal of General Systems, 38:2, 103-110, DOI: 10.1080/03081070802643402 (This is the source of the photo, above, of Ashby at his desk).

Byles, R.B. 1911. The card index system; its principles, uses, operation, and component parts. London, Sir I. Pitman & Sons, Ltd.

F. Heylighen, C. Joslyn and V. Turchin (editors): Principia Cybernetica Web (Principia Cybernetica, Brussels), URL: cleamc11.vub.ac.be/ASHBBOOK….

Schmidt, J. (2016). Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine. pdfs.semanticscholar.org/88f8/fa9d…)

*Read more *:

The Hashtags of a cyberneticist

Even the index is just another note

To illustrate that claim, here’s a dynamic index of my Zettelkasten articles

Soon we'll all be writing the books we want to read

To benefit from AI-assisted writing, look closely at how it’s transforming the readers.

Whenever new technologies appear, many changes in the economy happen on the consumer side, not the producer side.

As AI-assisted writing disrupts the writers, it will do so mainly by transforming the readers.

Reading Confessions of a viral AI writer in Wired magazine made me realise I had the future of AI-assisted writing the wrong way around. Vauhini Vara’s article shows how AI is already making a massive difference to our expectations of writing. She’s a journalist and author who has seen her working practices upended. But what about the readers? Sure: production is undergoing massive disruption.

But meanwhile the consumption of writing is on the cusp of a complete revolution.

In the old days you used to stand at the grocery store counter while the staff fetched all the groceries for you, and at the fuel station an attendant would fill up your vehicle’s tank on your behalf. Then new technology transferred these tasks from the seller to the buyer, and the buyer had no real say in the matter, so that by now it’s completely normal to walk down a grocery aisle filling the trolley yourself, or to operate the fuel hose on your own.

No one pays you to do this work that the employees used to insist on doing.

It’s the same for all kinds of office work. The managers do their own budgeting using spreadsheets, while the staff do all their own typing. No one expects to find a typing pool at work. In fact, few workers are even old enough to have seen one.

Move forward a few years and social media has completely adopted this labour-shifting approach.

All the work of social networks is done by the customer.

On YouTube, Instagram and TikTok, the users literally make their own entertainment.

The consumer is now the producer. And this is exactly how it’s going to be with AI-assisted writing.

In former times other people, professionals, wrote books for you. They were called ‘writers’ or ‘authors’, and they, in turn, called you a ‘reader’. But the new technology is shifting the workload to the consumers. We won’t really have a choice, no one will pay us, and eventually we’ll come to see it as completely normal.

“If there’s a book you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” — Toni Morrison

From now on the readers will use AI to write the books they want to read.

‘Professional writer’ will be a job like ‘bowser attendant’ - almost forgotten. Certainly the books still need to be written, just as the fuel tank still needs filling, but why not just let the reader write the books themselves? Who better to decide what they want?

Soon we’ll all be authors, each of us writing for a single reader - ourselves.

These categories, reader and writer, used to be obviously distinct. But AI will result in only one category. Maybe we’ll even need a new name for it.

But as every marketer and advertiser knows, people are completely out of touch with their own taste - they need someone to show them. Fashion, celebrity - consumerism is an ideology that requires followers.

The writers will have a new job: advising people on how best to describe their own desires.

A further, more tentative prediction: AI will also assist the general public to write computer programs. The programmer’s job will shift towards advising the public on what software they actually want to write.

Footnote: I’ll revisit this article in five years to see how accurate my crystal-ball-gazing really is!

Image source: How it was: life in the typing pool

See also:

Even the index is just another note

It’s tempting to place your notes in fixed categories

At some point in your note-making journey you’ll notice that quite a few people like to place their notes in fixed categories according to some scheme or other. The ancient method of commonplaces held that knowledge was naturally organised according to loci communis (common places). Ironically, no one from Aristotle onwards could ever agree on what the commonly-agreed categories were. Assigning your notes to categories is consistent with the ‘commonplace’ tradition, but that’s not what the prolific sociologist Niklas Luhmann did with his Zettelkasten, and furthermore it runs exactly counter to Luhmann’s claim in ‘Communicating with Slipboxes’, where he said:

“it is most important that we decide against the systematic ordering in accordance with topics and sub-topics and choose instead a firm fixed place (Stellordnung).”

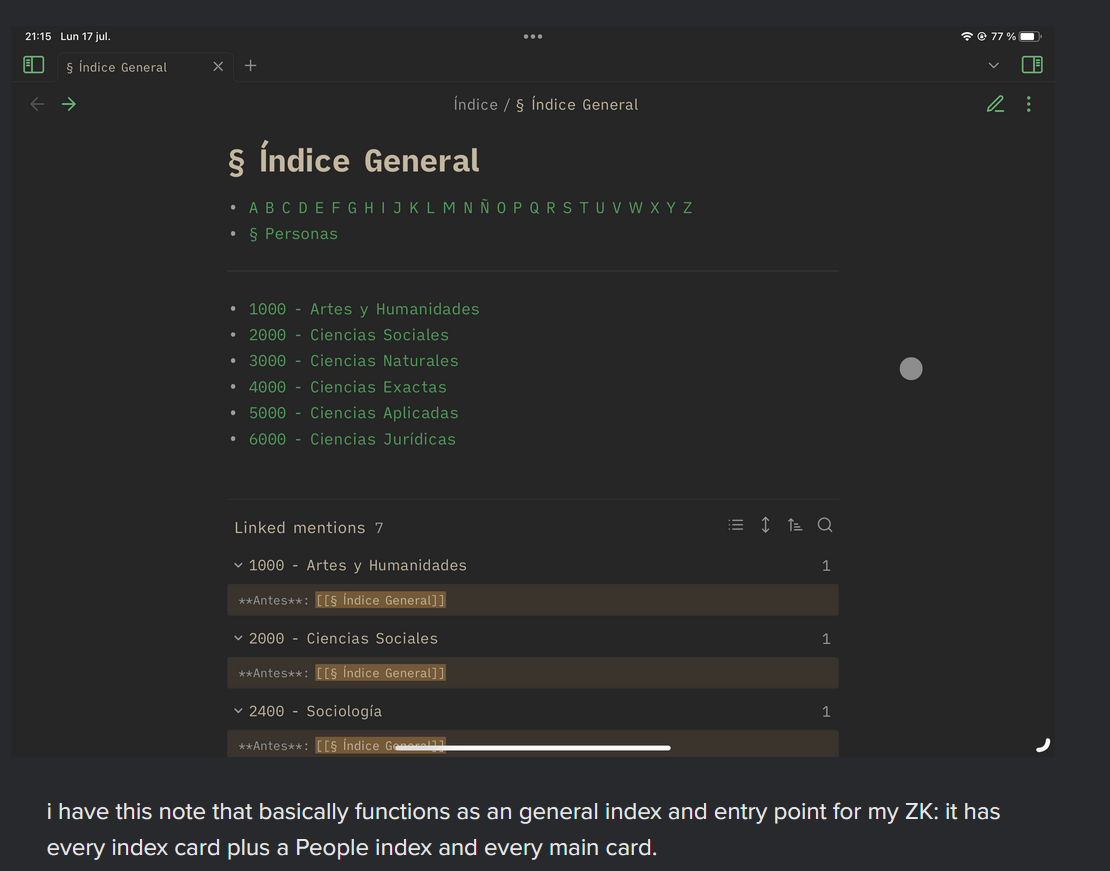

But there’s no need to despair, there is a way through the impasse! After all, what exactly is a subject or category? The subject or category index itself, it turns out, is nothing other than just another note. Here’s a real-life example:

“i have this note that basically functions as an general index and entry point for my ZK: it has every index card plus a People index and every main card.” - u/Efficient_Earth_8773

When everything’s a note, even the categories are just notes

Why does this matter? If even the index is just a note, then you haven’t constrained yourself with pre-determined categories. Instead, you can have different and possibly contradictory index systems within a single Zettelkasten, and further, a note can belong not only to more than one category, but also to more than one categorization scheme. Luhmann says:

“If there are several possibilities, we can solve the problem as we wish and just record the connection by a link [or reference].”

When even the index is just a note, a reference to a ‘category’ takes no greater (or lesser) priority than any other kind of link. This is liberating. Where a piece of information ‘really’ belongs shouldn’t be determined in advance, but by means of the process itself.

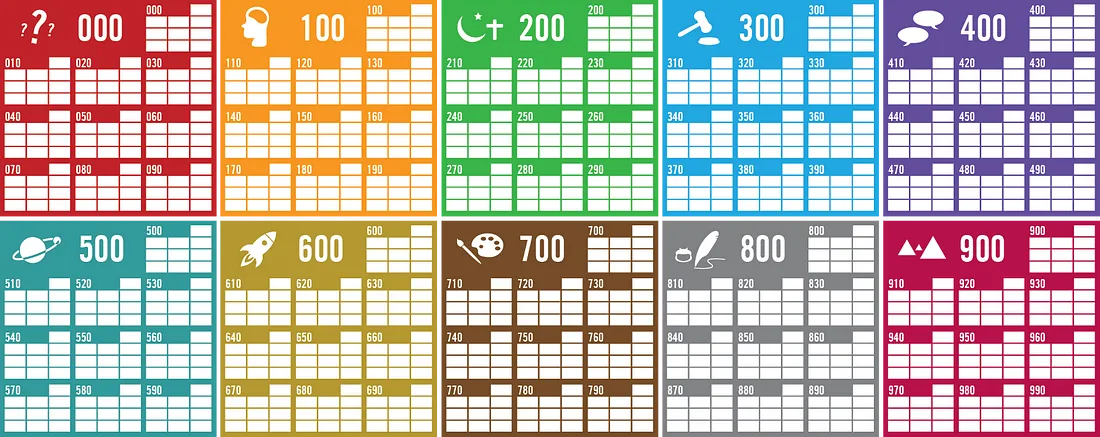

The Dewey Decimal System pigeonholes all knowledge, like cells in a prison.

Some people want an index, like folders in a filing cabinet, or subject shelves in the library. Well they can have it: just write a note with the subjects listed and make them linkable. Some people don’t want this, and they can ignore it. I personally don’t understand why you’d want to set up a subject index that mimics Wikipedia or the Dewey Decimal system, or even the ‘common places’ of old. I’m neither an encyclopedist, a librarian, nor an archivist. What I’m trying to do is to create new work. I want to demonstrate my own irreducible subjectivity by documenting my own unique journey through the great forest of thought. My journey is subjective, because it’s my journey. I’m pioneering a particular route, and laying down breadcrumbs for others to follow should they so choose. It’s unique, not because it’s original but because the small catalogue of items that attract me is wholly original. As film-maker Jim Jarmusch said:

“Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic.” (I stole that from Austin Kleon).

But that’s just me (and Luhmann).

Make just enough hierarchy to be useful

Having thought a bit about this I’m inspired now to sketch my own workflow, to see how it… flows. In general, I favour just enough data hierarchy to be viable - which really isn’t very much at all. I’m inspired by Ward Cunningham’s claim that the first wiki was ‘the simplest online database that could possibly work’. Come to think of it, this may be one of the disadvantages of the way the Zettelkasten process is presented: perhaps it comes across as more complex than it really needs to be. As the computer scientist Edsger Dijkstra lamented,

“Simplicity is a great virtue but it requires hard work to achieve it and education to appreciate it. And to make matters worse: complexity sells better.” - On the nature of Computing Science (1984).

If you must have hierarchies like lists and trees, remember that they’re both just subsets of a network.

Source: I don’t know. If you do, please tell me ;)

See also:

Three worthwhile modes of note-making (and one not-so-worthwhile)

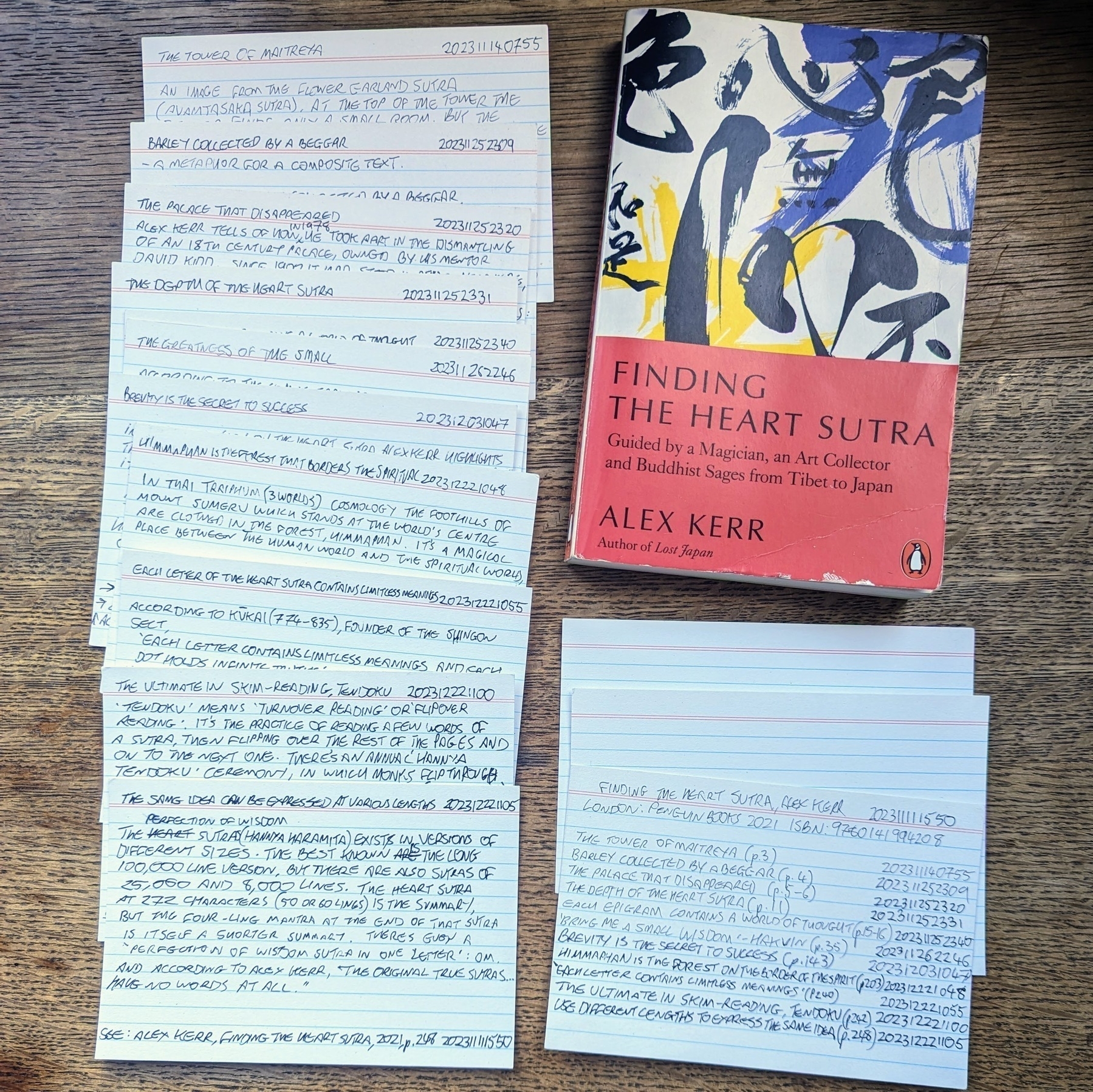

I finished reading Alex Kerr’s Finding the Heart Sutra on New Year’s Eve, so it just scraped into my reading for 2023. And while reading I made notes by hand, as I’ve done before. Although there aren’t very many notes (just eleven, plus a literature note that acts as a mini-index), they’re high quality, since I found the book very interesting.

I don’t mean I’ve written objectively ‘good’ notes. Rather, I mean the notes are high quality for my purposes. Everyone who reads with a pen in hand is an active reader, so the notes one person makes will be different - perhaps completely different- from the notes another person makes. In any case, no two readers read a book the same way.

Reflecting on this it seems to me there are at least three fruitful ways, or modes, of making notes while reading, as follows: Free-form, directed, and purposeful note-making.

Each of these note-making modes has its place, but in this particular case I was reading Finding the Heart Sutra with a very specific project in mind. So the notes I made were also quite specific. I imagine that someone else would be surprised by the notes I made, since they don’t really reflect the contents of the book. For instance, my notes are definitely not a summary of the book’s contents. Nor do they even follow the main contours of the book’s themes. Instead, I was making connections while reading with the main concerns of my own project. Each of my notes stands in its own right and could potentially be used in a variety of different contexts, but collectively, they make sense in relation to my own preoccupations. They fit into my own Zettelkasten, and no one else’s.

“Most great people also have 10 to 20 problems they regard as basic and of great importance, and which they currently do not know how to solve. They keep them in their mind, hoping to get a clue as to how to solve them. When a clue does appear they generally drop other things and get to work immediately on the important problem. Therefore they tend to come in first, and the others who come in later are soon forgotten. I must warn you, however, that the importance of the result is not the measure of the importance of the problem. The three problems in physics—anti-gravity, teleportation, and time travel—are seldom worked on because we have so few clues as to how to start. A problem is important partly because there is a possible attack on it and not just because of its inherent importance.”

If you want to know more about how to read a book, you could do worse than read How to Read a Book, by Mortimer Adler. It’s not the last word on the subject, but it’s a good starting point.

And it’s a warning against a fourth mode of note-making that I don’t advise: encyclopedic note-making. This is where you read a book and try to write a summary that will work for everyone. First, it’s hard work, and secondly, it’s probably already been done. If you open the link above you’ll see that the Wikipedia entry for How to Read a Book already includes a summary of the book’s contents. There are circumstances where the careful and complete summary is worthwhile, but I suggest you only start this task with the end - your own end - in mind.

If you have thoughts about making notes while reading, I’d be very interested to hear about it.

See also:

A note on the craft of note-writing

Learning to make notes like Leonardo

Raising babies? Here's how to survive - I mean, enjoy it

Ben Werdmuller may not be alone in finding it quite a challenge raising a baby while also having a life. Here are some thoughts from my own experience of parenting very young children.

tldr; I think I just about got away with it.

It’s just a phase

First, you will get through it. Though the feeling of being (over-) stretched and (completely) grounded may seem permanent, it really is just a short phase of your life. Before you know it, it will be over and you’ll miss it. So the important thing is to lean into the constraints. This is now, and even though it may seem like an eternity it won’t be like this for very long. Children grow very fast and you miss every stage as they outgrow it.

Plan on returning to the things you abandon

Second, because it’s just a phase, you can afford to let go of a few things - even things that seem indispensable. A bit like how at the end of the day you go to sleep thinking “that will just have to wait till tomorrow” - some things will have to wait till the kid grows up a bit and is a bit more independent. I noticed that even as pre-school arrived, my kids needed much less of me and much more of their peers. Then, at the age of about 5, they had a less independent phase. It goes in waves but in general they need your time less intensely the older they get. I did a graduate diploma in psychology when they were teenagers and they didn’t even notice. Those things you really need to do this year? Well, you prioritised kids (theory) so now you need to prioritise your time with kids (practice). Create a three or five year plan which includes ramping up the things you do without the kid, so you know those days really are coming, with a little patience.

Find something nurturing in every little thing

Third, “If you have a young family and you are managing to spend time on creative work…” Yes, I’m getting to that! Even though you’re now travelling at the speed of a baby, you can still experience something for yourself in almost every activity. I remember visiting Seattle with a toddler and a baby. We saw every children’s playground and not much else really. But hey! I visited Seattle! There was a fish ladder too, as I recall. The Bumbershoot music festival? There was a ride where you go round and round slowly in a large toy car. Oh, and space noodles at the Space Needle. Most importantly though, I did it with my tiny children. Thomas Merton said it more eloquently:

“if we have the courage to let almost everything else go, we will probably be able to retain the one thing necessary for us — whatever it may be. If we are too eager to have everything, we will almost certainly miss even the one thing we need. Happiness consists in finding out precisely what the “one thing necessary” may be, in our lives, and in gladly relinquishing all the rest.” - Thomas Merton,No Man Is An Island.

Find the others

Fourth, find some allies and make a community of peers. You can’t actually do it all on your own. That trip to Seattle? We were on a journey across the world, emigrating to Australia, to live in a town where I knew precisely no one. Very quickly we set up a baby-sitting circle, then on the back of that a local economic trading system (LETS) for the same families, using washers as credits, and I joined the community garden toddler group, and before long we had a group of adults to do baby activities with together, so the baby stuff wasn’t just baby stuff - it was social activity for the adults too. By sharing the load, both my partner and I managed to get a lot of writing done in the time we had very young kids. Also, some of those people we met through mutual desperation weren’t just temporary allies. They became our close friends. Yes, raising children slowed us down, and not all of our aspirations were fulfilled (putting it mildly), but both our kids are young adults now and though this is fantastic, I miss them as babies terribly. Would I go back there? Yes, in a flash.

To sleep, perchance to dream

Fifth, sleep and tiredness? Absolutely. It’s actual torture. Easy to say and hard to do, but sleep when the baby sleeps. Far from perfect, and usually far from doable, but wherever possible, get those micro-sleeps in. Compared with chinstrap penguin parents, who sleep for 4 seconds at a time throughout the day, human parents have it easy. They might get at least ten seconds at a time. Well, that’s obviously no help at all, but to refer back to point one: you will get through it. And I found meditation really helped, though YMMV.

Baby advice is absolutely the worst advice

Well no one ever benefited from offering unsolicited baby-raising advice. I mean, either it sounds unbearably smug, as in “just be a good parent and it will work out fine”, or completely unhelpful, as in “have you tried just turning the light off?”, or “it’s just a phase” (sorry about that).

Now you’ve seen my poor attempt at being the exception to the rule, what are your top tips for annoying your friends who have young babies?

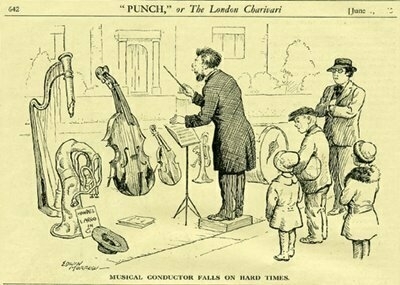

Conducting myself properly

They made me the student leader of the school orchestra. One day the music teacher was sick and he asked me to conduct. I had no idea what to do, except what I’d seen him doing. So I waved my arms around.

Today I’m fragmented, overwhelmed by what there is still to complete, and also by all there is to start. Somewhere in the middle, there I am, lost between starting and finishing. Flailing.

Yet even no method is still a method. Says the poet Christian Wiman1:

💬 “The truth is our only savior is failure.”

And look at those stats! This is my 200th post here this year. Writing slowly? No, not me.

The real story of Napoleon?

If you’re thinking of viewing Ridley Scott’s movie version of Napoleon 🍿, or if you’ve already seen it, I’d recommend also reading The Black Count: Glory, Revolution, Betrayal, and the Real Count of Monte Cristo by Tom Reiss. 📚

This Pulitzer prizewinning biography puts Napoleon’s life and times in historical context and it’s an amazing story. The ‘black count’ of the title was Alexandre Dumas, father of the famous author of The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers. He rose from obscurity to became Napoleon’s commander of cavalry during the Egyptian campaign.

But quite unlike Napoleon, he seems to have been motivated by something rather more than personal glory. He actually believed in the ideals of the Revolution, not least the implementation of Liberté.

As an aside, the book provides a huge number of fascinating factoids, such as why dolomite (the mineral as well as the mountain range) is named dolomite.

Why I'm writing faster

Why do you write?

Everyone has their reasons but I write so I can think:

Writing is not simply a way of saying what someone knows but one of the most effective ways to unveil what there is to say. As Baker (1985) suggests, “in fact, writing creates a thought and the capacity to think: with writing you discover thoughts that you barely knew you had”

But what slows you down?

I’ve been running this site, and writing slowly since 25 January 2014. For the first nine years it really lived up to its name, because I posted very rarely. The reason, I reasoned, was that the WordPress front end and I just didn’t get along. It was a room of my own, sure, but it wasn’t comfortable. It just didn’t feel like a room I wanted to spend time in.

The author Virginia Woolf wrote about how women need a room of one’s own to write in. But that still left the rest of the world to the men. Jane Austin wrote at the kitchen table of a busy household, and it wasn’t ideal. Capitalism gives us hot-desking - not even a table to call your own. So your virtual environment really matters. A UI of your own? Not likely.

And what speeds you up?

Eventually, after complaining about WordPress for five years, and having tentatively connected the site to micro.blog (not before eight months of procrastination) while still hosting it on WordPress, I finally switched completely to micro.blog as the host. This meant the front-end editor also changed completely. Now I just had a plain box to write in, with a couple of options for simple categories. Often though, I just wrote in a text editor and copy-pasted as necessary. The outcome was stark. This shift resulted in a dramatic increase in writing frequency, which given the name of the site is a little embarrassing. On 27 January 2023 I wrote:

“Don’t worry, whatever happens I’ll still be writing slowly.

Between 2014 and 2022 I had only written 26 posts. But following the big changeover I wrote 194 posts and counting, in a single year. As a result there’s now about 33,000 words on this site. And here are the latest statistics.

So what’s the right speed for you?

I admit it then: I’ve sped up. Yet I still maintain that writing slowly is the way to go. A little every day or two adds up to a whole heap. Never mind the quality. Just look at the size! Maybe I’ll change the name of this site to Writing Bigly.

“Don’t worry, whatever happens I’ll still be writing bigly.”

Well clearly that won’t be happening. Meanwhile, though, I wish you a very big writing year ahead. Let me know in the comments what you’ve achieved, and what you have planned. Exciting!

More on writing and blogging

Publish first, write later

“Literature is perhaps nothing more complicated and glorious than the act of writing and publishing, and publishing again and again."

- Marcelo Ballvé, on the curious writing career of César Aira

César Aira on the constant flight forward

Argentinian author César Aira’s writing process is more about action than reflection. In a moment I’m going to share with you an extract from The Literary Alchemy of César Aira, an essay by Marcelo Ballvé, originally published in The Quarterly Conversation in 2008.

But before coming to the extract, I’ll just comment on David Kurnick’s claim in Public Books that Aira’s work is primarily about process:

“It is not in the least original to begin talking about César Aira’s work by recounting the technique that produces it. But it can’t be helped: Aira has made a discussion of his practice obligatory. To read him is less to evaluate a freestanding book, or a series of them, than to encounter one of the most extraordinary ongoing projects in contemporary literature.”

True, I’m not being at all original here, just cutting and pasting. Still…

Aira’s own Aleph

It’s as though through his writing Aira has found the basement in Buenos Aires that contains the entire universe in condensed form, the basement that features in Borges’s 1945 story “The Aleph”.

And having found that fabled basement, it’s as though Aira has taken on the persona of Carlos Argentino Daneri, the character in Borges' story whose life’s obsessive goal is to write a poetic epic describing each and every location on Earth in perfect detail.

But instead of taking the find seriously, Aira parodies it. Everything is here: and what do you know? None of it makes sense! Or, perhaps instead of parodying “The Aleph”, he takes it completely seriously: Why not write about it, about all of it? What then? In an interview in 2017 for the New Yorker, Aira said: “I am thinking now that maybe . . . maybe all my work is a footnote to Borges.”

Of course I’m not just cutting and pasting. I’m writing too. Aira also inspires my own writing process. His example inspires me to choose my own race - and finish it.

One of my role models is the Argentinian author César Aira. He’s written a very large number of novels and novellas (at least 80 - around two to five per year since 1993), published by a variety of presses. That’s a lot of races and a lot of finish lines crossed.

Now here’s Marcelo Ballvé on Aira’s unique writing process.

According to Aira, he never edits his own work, nor does he plan ahead of time how his novels will end, or even what twists and turns they will take in the next writing session. He is loyal to his idea that making art is above all a question of procedure. The artist’s role, Aira says, is to invent procedures (experiments) by which art can be made. Whether he executes these or not is secondary; Aira’s business is the plan, not necessarily the result. Why is procedure all-important? Because it is relevant beyond the individual creator. Anyone can use it.

Aira’s procedure, which he has elucidated in essays and interviews, is what he calls el continuo, or la huida hacia adelante. These concepts might be translated into English as “the continuum,” and a “constant flight forward.” Editing is an abhorrent idea in the context of Aira’s continuum. To edit oneself would be to retrace one’s steps, go backwards, when the idea is to always move forward. To judge yesterday’s writing session, to censor a lapse into the absurd or the irrational, to revive a character your work-in-progress sent tumbling over a cliff—all of these actions go against Aira’s procedure. Instead, the system prioritizes an ethic of creative self-affirmation and, I would say, optimism. To labor to justify previous work with more strange creations that in turn establish the need for ever more artistic high-wire acts in the future—this is the continuum, the high-wire act the artist must perform when he refuses to submit to any rule that is not his autonomously chosen procedure. It is an act performed with deep abysses yawning to each side of him—conformity, market pressures, conventionality, self-repression of all kinds . . . In other words, Aira’s literary career, embodied in each of his 63 novels, is a reckless pursuit of artistic freedom.

Aira says that when he sits down to write his daily page or two, he writes pretty much whatever comes into his head, with no strictures except that of continuing the previous day’s work. (The spontaneous feel of his stories would seem to back up this claim, but I’ve always asked, can anyone write as well as Aira does while simply letting the pen ramble?)

True, his books are very short. Aira says in interviews that he’s often tried to make his novels longer, but they seem to come to a natural rest at around the 100-page mark. Technically, much of what Aira has written would have to be classified in the novella category, but it’s hard to classify Aira’s work within any genre, be it story, novel, or novella. In my mind, Aira’s creations are something different altogether. They are stories, pure and simple, which Aira has managed to ennoble by seeing them into publication in the form of a single book. What he has done is put stories into circulation as objects, which is a defiant feat when seen in the context of a global literary market that demands hefty, sprawling, “big” novels.

The key to Aira’s curious career, I think, is to be found in his conception of literature as something with more affinities to the realm of action than the inner world of reflection. Literature is perhaps nothing more complicated and glorious than the act of writing and publishing, and publishing again and again. Editing is dispensable, so is the search for the “right” publisher. (Aira publishes seemingly with whomever shows any interest in his manuscripts; at least a dozen publishers, most of them small independents, in Argentina alone.) The idea seems to be: publish first and ask questions later…In fact Aira’s mentor, the deceased Argentine poet and novelist Osvaldo Lamborghini had a saying: “Publish first, write later.”

Extracted from The Literary Alchemy of César Aira, by Marcelo Ballvé. The Quarterly Conversation

César Aira’s main publisher in English is New Directions. They’ve published about 21 of Aira’s works in translation, while And Other Stories has published another half-dozen.

Now read: Choose your own race

Choose your own race and finish it

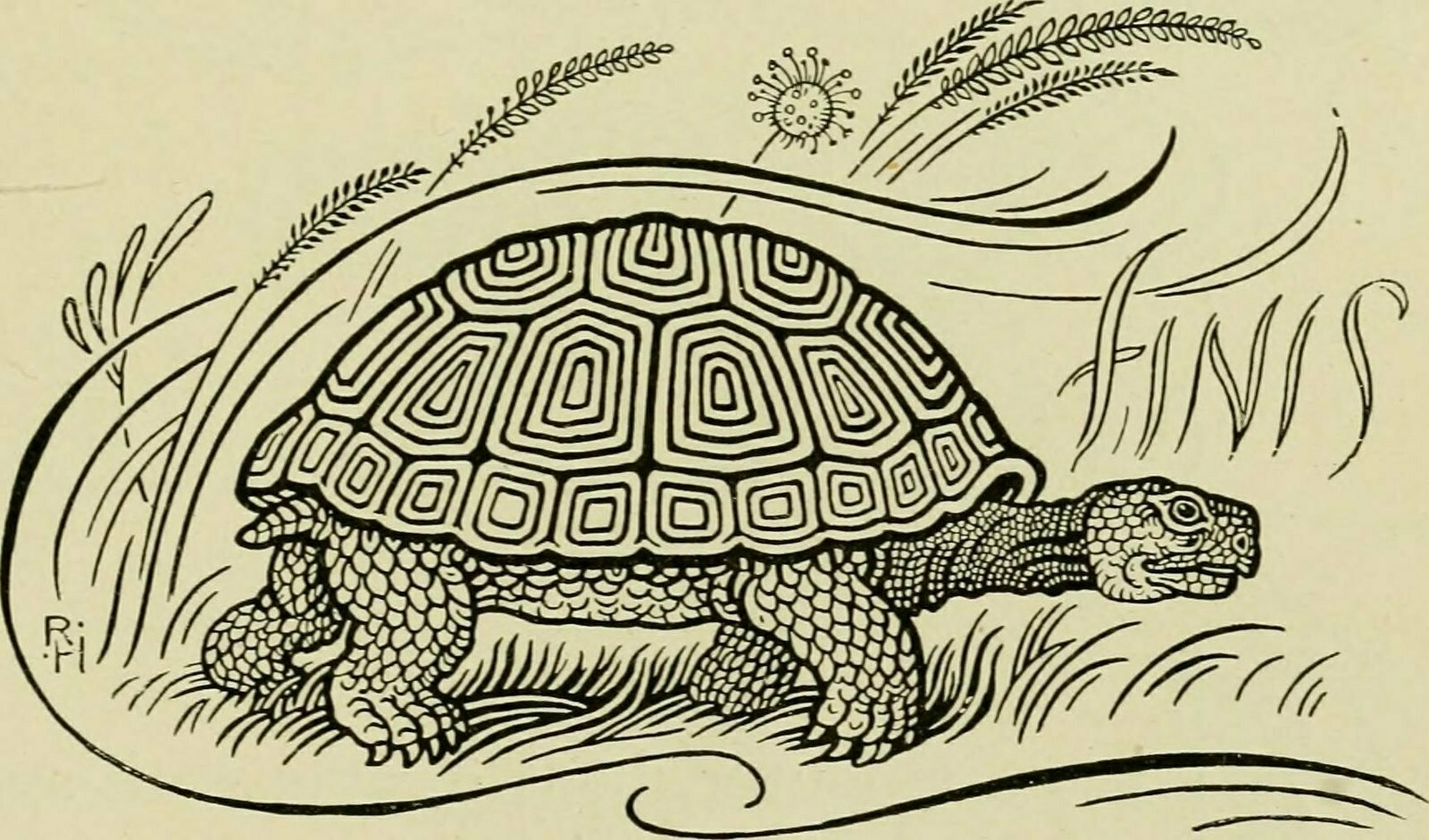

Are you Hare or Tortoise?

The idea of writing slowly appeals to me because it comes from Aesop’s fable of the hare and the tortoise. Perhaps you remember it.

The hare challenges the tortoise to a race, which he’s obviously the favourite to win. Everyone knows a hare moves much faster than a tortoise. As expected, the hare shoots ahead, then slows for a well-deserved rest, since there’s no way the tortoise will ever catch up. Meanwhile, the tortoise just plods along and eventually passes the hare, who has fallen into a deep sleep by the side of the road. The hare wakes up, just in time to watch the tortoise cross the finish line first.

Now perhaps the moral of the story is something like: slow and steady wins the race. Well, sure, that’s a good moral. And it’s true too: if you just keep on going you’ll achieve far more than if you give up. Obviously.

Another popular interpretation is that ‘pride comes before a fall’. Everyone knew the hare was fast, so why did he have to boast about it? And by trying to beat a tortoise, of all creatures?

I think of myself as someone who hasn’t been quick to publish. I think that because its completely, starkly true. There are others much quicker than me (for example, everyone who ever published). But if publishing quickly is your key metric, there’s now a big problem.

Too fast to keep up

On Amazon there are hundreds or even thousands of genre fiction writers who are writing a novel a month or even faster, just to satisfy the voracious appetite of the algorithm. If they slow down their pace even a little, the site loses sight of them and they risk sinking back down towards obscurity - so all they can do is keep going, writing faster and faster, and with the assistance of AI tools if necessary. In relation to these prolific authors, everyone is writing slowly.

But now that AI has worked out how to tell a coherent story too, the humans, however fast, have no chance. Bots are writing for themselves, and they can write far, far quicker than any human could possibly keep up. If all that matters is quantity, we’re sorted - AI will make mountains of it.

In 2023 for example, the news reported literary journals closing their books to new entries because they were simply overwhelmed by automated entries that the editors couldn’t tell apart from the stories written by humans. And with so many entries they didn’t have time to check anyway1.

So from now on, by most metrics, all humans are writing slowly. Let’s face it, in relation to the machines, we’re second best, no longer gold medal material. It’s enough to induce a bout of Promethean shame.

Each of these moments of innovation involves an emotion similar to what German philosopher Günther Anders called ‘Promethean shame’. This is the feeling that technology is embarrassing us by pointing out our human limitations. We’re just not as good at doing things as the tech that we invented to ‘help’ us do it. In Anders' original formulation the shame arose in the observation of high quality manufactured goods. What was it shame of? That we were born, not manufactured (Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen, 1956). In the face of the latest AI panic, we’re asking, yet again: if the tools don’t really need us, what’s the point of humans at all?

Keep your eye on the finish line

But for me, the key message of the fable of the hare and the tortoise isn’t about how you’ll win the race if you just keep going. I don’t really have any problem with keeping going. I’m tenacious and have a lot of inertia. That means I find it hard to start, but equally hard to stop. No, for me the moral of the fable of the hare and the tortoise is quite different.

The story reminds me that I’ve only won when I cross the finish line. Anything else isn’t a victory. That means it’s OK to write slowly, but what I need to keep sight of is finishing something, anything, and shipping it. It’s not enough to actually write, however fast or slow. What matters is publishing, in whatever form, for whatever audience.

But maybe the process is what matters

One of my role models is the Argentinian author César Aira. He’s written a very large number of novels and novellas (at least 80 - around two to five per year since 1993), published by a variety of presses. That’s a lot of races and a lot of finish lines crossed.

Even if you met another Aira fan it would be unlikely you’d both have read the same Aira books, because there are just so many of them. And of course, Aira’s has written a novel called The Hare - but who, even among Aira enthusiasts, has read it? In other words, Aira’s oeuvre is more the record of a particular creative process than it is a body of work to be read in its entirety.

Indeed, the critic Marcello Balvé says Aira’s many novels are “stepping stones, a trail of crumbs leading to a place as close to the molten heart of creation as it is possible to come without burning up.” That’s a bit overheated, but why not2?

Which way are you running?

The story of the hare and the tortoise reminds me too that while I can’t really control my top speed, I can at least control the length and direction of the race I’m running. I often think in terms of writing a whole book, or even a series of books - only to feel overwhelmed by the enormity of the task I’ve set myself.

But it doesn’t have to be like this. Aira only writes short books, but he publishes roughly two a year. A book is made out of chapters, and chapters are built from sections, and sections are made from paragraphs and sentences. In fact, the road to a complete book passes necessarily through a series of completed short pieces, each no harder to write than this one I’m writing right now. I could rein in my ambitions, and publish as I go, one idea at a time.

That way, instead of never completing anything, I’ll always be completing something. And publishing it for you to read, exactly as I’m doing now.

But whether I’m a tortoise or a hare, or even a person who resists anthropomorphizing animals just for the sake of a cheap fable, or even a person who’s uncomfortable with running and competition metaphors, all the same I’m running my own race: watch me win.

More on writing slowly

You can get a lot done by writing slowly

Thoughts are nest-eggs. Thoreau on writing

More on Artificial intelligence (AI) and large language models (LLMs)

Despite AI, the Internet is still personal

Can AI give me ham off a knee?

More than ever, embracing your humanity is the way forward

Jules Verne could have told us AI is not a real person

Gaslit by machinery that calls itself a person

In eight different ways, to have a friend is to be one

A few years ago, Barking Up The Wrong Tree reflected on research 1 that identified the eight different kinds of friends you need. But it struck me that this is really a primer on the eight different kinds of friend you need to be to others.

Remember the old saying, “to have a friend is to be one”? Well there’s more than one way you can be a friend to someone and you’re probably not making the most of all your opportunities here. I’m not saying you should try to cover all the bases. It’s unlikely any one person could really fulfill all the eight roles to best effect. Instead, I’m using this as a checklist to reflect on:

I’m also using this as a way of being more reflective about what my various friends actually need from me. For example, I tend to do a lot of ‘mind-opening’, but actually, this may not always be very useful. If I’m honest, it might well just be annoying.

“What do you need right now?” might be a good phrase to practice!

Eight ways to be a friend

Is domain-hosting a viable social media business model?

Since July 2023 BlueSky has apparently learned from Manton Reece and micro.blog that you can run a sustainable and open social media network with a domain-hosting business model.

Almost learned. There’s a way to go yet, with a big missing owning your content piece.

Meanwhile, micro.blog cross-posts automatically to BlueSky, so the #Interverse1 is gradually becoming a reality. 😍

“You can automatically cross-post your microblog posts to Medium, Mastodon, LinkedIn, Tumblr, Flickr, Bluesky, Nostr, and Pixelfed.” Source

I’m not using BlueSky myself. I really loved Paul Frazee’s work on BeakerBrowser, and it’s great he’s working on BlueSky. That’s very nearly enough to sign me up, but the venture capital vibe still puts me right off. I mean, ultimately it’s all just for the venture fund returns isn’t it?

I’m very happy just owning my content, and sharing it with you myself, with a little help from micro.blog and Mastodon. So thanks for reading, wherever you read.

Can you make your autobiography out of hashtags?

Image credit[^1]

Image credit[^1]

The hashtags of a cyberneticist

In 1963 Ross Ashby, the British cyberneticist and inventor of the automatic homeostat, engraved a tiny schnapps glass with a list of things his wife liked. He called this gift A Cup of Happiness from Ross to Rosebud.

When I read the tiny spiral writing engraved on that glass it seemed like a very personal version of the hashtags by which, sixty years later, people on Mastodon or other social networking sites introduce themselves. But they are also a rather touching distillation of the couple’s life together.

Since reading this, I’ve been over-thinking what hashtags I might use for this purpose, and Ross Ashby’s attempt has inspired me. Not that my hashtags would be anything like these, but their bourgeois English everyday intimacy does have a certain kind of charm. As a historical document the list fairly oozes ‘mid-century anti-modern’! Here are the items, in full:

Jill ~ Pottery ~ Sally ~ TR2 ~ Ruth ~ Arranging flowers ~ Preserved ginger ~ ITMA ~ Shaffers ~ Steven ~ Dinard ~ Tennis ~ Mark ~ May Hill ~ John ~ Merrow Down ~ Richard ~ Lobster ~ Bread making ~ Michael ~ Clive Brook ~ Bear Lake ~ Chas. B Cochran ~ Auctions ~ Wood fires ~ Stratford ~ Terry’s ~ Gardening ~ Cookham ~ Tiddles ~ Repertory ~ Swimming ~ Bingen ~ Green Ridges ~ Sand castles ~ Ewhurst ~ Nov. 1926 ~ Cheltenham ~ Monday Night at Eight ~ Ouray ~ Delphiniums ~ Windon House ~ North Devon ~ Eau de Cologne ~ Dressmaking ~ Rhossilli ~ Tea ~ Palo Alto ~ Hot baths ~ Take it from here ~ Earrings ~ Cornwall ~ Geraniums ~ Painswick ~ Bear Grass ~ Oeufs Mournay ~ Furs ~ Vanilla slice ~ Crème de Menthe ~ Gt. Smith Street. Source

There are several different ways of reading this list. You can highlight interests:

Pottery, arranging flowers, tennis, bread making, gardening, swimming

Or you can name favourite places and houses:

Shaffers, Dinard, May Hill, Merrow Down, Bear Lake, Stratford, Cookham, Bingham, Ewhurst, Cheltenham, Ouray, North Devon, Rhossilli, Palo Alto, Cornwall, Painswick, Terry’s, Green Ridges (the house they built)

You can remember favourite people:

Jill, Sally, Ruth, Steven, Mark, John, Richard, Michael,

Or shows:

ITMA, Monday Night at Eight, Take it from Here, Chas. B Cochran (impressario of Cole Porter and Noel Coward musicals)

Or favourite foods:

Preserved ginger, lobster, tea, oeufs mornay, vanilla slice, creme de menthe

Or beloved objects:

TR2 (the Ashbys' sports car), wood fires, sand castles, delphiniums, eau de cologne, hot baths, earrings, geraniums, bear grass, furs

Or special moments:

Nov. 1926, Gt Smith Street (the place in central London where the couple first met)

According to the Ross Ashby information site, Tiddles was their cat. The rest we have to work out for ourselves.

What do your own hashtags say about you?

If you think about your own list of hashtags, I wonder which personal ones you left out, since the Internet doesn’t need to know everything about us (read: has already categorised us to the minutest detail).

For example, web developer Jeremy Keith has a ‘bedroll’ list on his website of people who have visited his house in Brighton. Who else does this?! Hashtags may be quite generic, but in combination they can tell a unique story.

Cybernetics revisited

Clearly no mention of Ross Ashby can go without reference to cybernetics, which is seemingly back in fashion. As the AI revolution takes off there’s a renewed interest in revisiting the aims of the earlier cyberneticians, and to some extent their methods. A new School of Cybernetics has recently opened at the Australian National University (part-funded by Microsoft, Meta and others), with a public exhibition that took place until 2 December 2022. The school is led by Prof Genevieve Bell, a former vice president of Intel.

The claim is:

“We focus on systems – rather than specific technologies, or disciplines—as the unit of analysis. Cybernetics offers a way of transcending boundaries, of thinking in systems and ensuring that humans, technology and the physical environment are in the frame as technology advances and transforms the world around us. It is a way to imagine humans steering technical systems safely through the world.”

And there’s plenty more on what they’re calling ‘the new cybernetics’.

I can’t help thinking: there’s a lot of politics in who gets to do the steering. The culture of Microsoft and Meta is powerfully to resist being steered, at every possible opportunity, law-suit by law-suit for eternity. Cyberneticist Stafford Beer’s support for the socialist Allende government of Chile is probably not a model they’re all that interested in. But if you are interested in what might have been, you could do worse than listen to Evgeny Morozov’s podcast, The Santiago Boys. I’ve found it fascinating.

A note on the craft of note-writing

An fairly new article from Brazil caught my eye, on note-writing as an intellectual craft. It highlights the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann’s note-making process (he put his many linked notes in a Zettelkasten - an index box).

Cruz, Robson Nascimento da Cruz, and Junio Rezende. “Note-writing as an intellectual craft: Niklas Luhmann and academic writing as a process.” Pro-Posições 34 (2023).

<doi.org/10.1590/1…>

https://www.scielo.br/j/pp/a/L7gmq6W7bvzgn984hSJ94

Abstract: "Despite numerous indications that academic writing is a means toward intellectual discovery and not just a representation of thought, in Brazil, it is seen more as a product of studies and subjects than an integral part of university education. This article presents note-taking, an apparently simple and supposedly archaic activity, as a way through which academic writing is eminently oriented towards constructing an authorial thought. To this end, we discuss recent findings in the historiography of writing that show note-taking as an essential practice in the development of modern intellectuality. We also present an emblematic case, in the 20th century, of the fruitful use of a note-taking system created by German sociologist Niklas Luhmann. Finally, we point out that the value of note-taking goes beyond mere historical curiosity, constituting an additional tool for a daily life in which satisfaction and a sense of intellectual development are at the center of academic life."

Yes, Esperanto is idealistic - not that there's anything wrong with that

The child who learns Esperanto learns about a world without borders, where every country is home.

Yes, Esperanto is idealistic…

The Prague Manifesto of the 1996 World Esperanto Congress promoted seven objectives, goals or principles of the Esperanto movement.

It positioned Esperanto as a movement for:

…and what’s wrong with idealism?

Even without knowing any Esperanto, I applaud these aims. They’re idealistic and so am I. But if the aim is human emancipation, is it possible that the language itself is just a MacGuffin? Not that there’s anything wrong with that, as they’d say on Seinfeld.

On the other hand, perhaps it is still possible to imagine not only a different language, but a different kind of language - one that by its very existence helps promote the kind of values outlined by the Prague Manifesto.

If you’re an Esperanto speaker, or if you speak another ‘international auxillary language’, I’d like to know what you think.

How many books are you reading?

On Mastodon, Evan Prodromou asked “How many books are you reading?” and I was slightly shocked by the results.

Only 5% of 569 people said they were reading six or more books. I thought I was quite normal, but it turns out I’m not. Currently I’m officially reading seven books, but that doesn’t include the four books I’ve finished recently that never made it onto the ‘currently reading’ list. Somehow, having a list of books I’m reading makes me want to read different books. I get through about 35-40 a year, which isn’t a terribly low number, so even though I get stuck on some books, seeming to take months to finish them, I still manage to read quite a few.

Perhaps I’m just starting into my to-be-read pile too early. Maybe I could resist this.

Actually I don’t think I’m at all normal, but everything I do feels normal. And who am I kidding? I can’t resist starting new books. Can you?

How to connect your notes to make them more effective

A linked note is a happy note

A great strength of the Zettelkasten approach to writing is that it promotes atomic notes, densely linked. The links are almost as valuable as the notes themselves, and sometimes more valuable.

But once you’ve had an idea and written it down, what is it supposed to link to? Is there a rule or a convention, or do you just wing it?

How are you supposed to make connections between your notes when you can’t think of any?

When I started creating my system of notes I didn’t know how to make these links between my atomic ideas, and this relational way of working didn’t come naturally to me. I would just sit there and think, “what does this remind me of?” Sometimes I’d come up with a new link, but more often than not, I didn’t. The problem is, the Zettelkasten pretty much relies on links between notes. An un-linked note is a kind of orphan. It risks getting lost in the pile. You wrote it, but how will you ever find it again? And if you do somehow stumble upon it again, it won’t really lead anywhere, because you haven’t related it to anything else.

Fortunately, there are some helpful ways of coming up with linking ideas that can really aid creative thinking and unlock the power of connected note-making.

Make a path through your notes with the idea compass

Niklas Luhmann, the sociologist who famously (to nerds) kept a Zettelkasten, didn’t exactly say this, but each atomic note already implies its own series of relations. Each note can be extended by means of the idea compass - a wonderful idea of Fei-Ling Tseng, as follows:

Notice how the first two questions promote a tree-like hierarchical structure, with everything nested in everything else, while the second two questions promote a fungus-like anti-hierarchical structure, with links that form a rhizome or lattice. Alone, the former structure is too rigid and the latter is too fluid. But put them together and they can be very powerful. The genius of the Zettelkasten system is that it absorbs hierarchical knowledge networks into its overall rhizomatic structure, without dissolving them, and allows new structures to form (Nick Milo helpfully calls these ‘maps of content’).

Find the larger pattern

Each atomic idea might be thought of as part of a larger pattern. In a sense, every note title is just an item in a list that forms a structure note at a level above it. Say I write a note on ‘functional differentiation’. I realise that this is just one component of a structure note that also includes ‘social systems’, ‘communication’, ‘autopoeisis’ and so on. I write this list, call it ‘Niklas Luhmann - key ideas’, and link it to my existing note. Now I have some ideas for some more notes to write. But will I write them all? No - I’ll only pursue the thoughts that actually interest me, or seem essential. The rest can wait for another day. Actually, I’m suddenly intrigued by what you could possibly have instead of functional differentiation (i.e. what is this note different from?), so I write a new note called ‘pre-modern forms of social structure’ - and link it back to my ‘functional differentiation’ note.

Look for the basic components

Going even further, the atoms, which seemed to be the smallest unit, turn out to be made of sub-atomic particles and so on, all the way down to who knows what (well, particle physicists might know, but I don’t). That means each atomic idea is really just the title of a structure note that hasn’t been written yet. So I take a new note and write: ‘Functional differentiation - the key points’. I imagine this new structure note to be like a top-ten list of important factors, each one ultimately with its own new note - but I’m not going to force myself to write about ten things that don’t matter, just what I find interesting.

When making links, trust and follow your own interest

It’s really important that you don’t try to answer all four questions with a new link. You’re not creating an encyclopedia. Instead, you should only make the connections that actually matter to you. The trace of your own inquisitiveness through the material is, in itself, important information. If it doesn’t matter to you, don’t write about it! Since the notes are atomic, and the possible links increase exponentially (?) the possibility space you are opening up is almost infinite and it can feel overwhelming. So just go with the flow. The key is to find your own curiosity and run with it. That way (as I’ve said before):

That’s what I’ve been doing this morning. At no point have I stopped to think “what shall I write next?” In this sense, the Zettelkasten is a kind of conversation partner. Niklas Luhmann said he only ever wrote about things that interested him. This seems unlikely until you try it for yourself.

And if you keep asking yourself these questions, you’ll find that over time the linking starts to come naturally. It will be increasingly obvious to you what relationships matter. The questions in the idea compass will become intuitive and fade into the background. Well, that’s my experience, but YMMV.

Apply a framework that intrigues you

Another way of making connections, besides the idea compass, is to apply a conceptual framework (or mental model) that interests you - and see where it leads. Here’s an example: Marshall McLuhan’s tetrad of media effects.

The idea here is that any new technology changes the whole landscape or ecology, by bringing some features into the foreground and pushing others into the background. It’s called a tetrad because there are four questions to ask of a new technology:

(This really clicked for me when I puzzled over why my kids don’t use smart phones for talking to people. It seemed crazy to me, but then I looked at question 3 and realised the new technology had retrieved asynchronous communication, which the telephone had previously made obsolete. But I digress.)

Anyway, I’m suggesting you might be able to take these four questions and ask them of the ideas in your notes. For each atomic note: what does this idea enhance, make obsolete, retrieve, or reverse?

Another simple but powerful example is Tobler’s law: “I invoke the first law of geography: everything is connected to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things”. What would it be like if you made everything about physical location?

It’s important to say these are just examples, and they may not work for you. Nevertheless, you may be able to think of frameworks from within your own line of work that allow you to ask a similar set of questions about your ideas. In my experience these frameworks are everywhere and yet are quite under-used.

This article is a lightly edited version of a Reddit comment.

You might also like to read about how a network of notes is a rhizome not a tree.

What is the real work of Serendipity?

Currently reading: The Real Work by Adam Gopnik 📚

The Real Work is what magicians call ‘the accumulated craft that makes for a great trick’, and the enigmatic S.W.Erdnase was a master. Adam Gopnik’s book on the nature of mastery devotes a whole chapter to him, so I was amused to find him also mentioned on the new series of Good Omens. This is a great example of the chance happening that people often confuse with serendipity. But as Mark De Rond claims serendipity isn’t luck alone. It’s really the relationship between good fortune and the prepared mind:

“serendipity results from identifying ‘matching pairs’ of events that are put to practical or strategic use.”

On this account it’s not luck or chance that matters, but the human agency that does something with it. From two chance encounters with S.W. Erdnase that seemed to match, I’ve constructed this short post. In his 2014 article, ‘The structure of serendipity’, De Rond identifies some examples of much more significant serendipity in the field of scientific innovation.

It strikes me that one significant feature of mastery is to be able to spot a lucky opportunity and then make something of it. The expert can’t help but see it. Everyone else would miss this chance moment, or else be unable to execute the essential implementation.

Reference: De Rond, Mark. “The structure of serendipity.” Culture and Organization 20, no. 5 (2014): 342-358. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2014.967451

Ted Nelson's Evolutionary List File

Rick Wysocki has a great post introducing Ted Nelson’s innovative idea for a new kind of file system. New, at least, in 1965.

Ted Nelson’s Evolutionary List File and Information Management

In many ways though, we’re still waiting for this kind of approach to become available.

The 1965 paper begins with a programmatic statement that has still not been fulfilled:

“The kinds of file structures required if we are to use the computer for personal files and as an adjunct to creativity are wholly different in character from those customary in business and scientific data processing. They need to provide the capacity for intricate and idiosyncratic arrangements, total modifiability, undecided alternatives, and thorough internal documentation.”

Ted Nelson, in case you don’t know, was the first person to coin the term ‘hypertext’, and this is the first published reference to hypertext. In his post, Wysocki reflects on the connections across decades between Nelson’s ideas and the contemporary interest in ‘personal knowledge management’ and Niklas Luhmann’s non-hierarchical Zettelkasten system of notes. He sees the Zettelkasten as potentially more creative than many contemporary systems because it doesn’t impose a fixed system of categories from the top down.

“Creating hierarchies and outlines of information can be useful, but many don’t realize that outlines have to work on existing material; they are not creative practices themselves (Nelson 135b). This is why the common myth we tell ourselves and our students that an outline should be worked on before writing at best makes little sense and at worst is cruel; how can we outline ideas we haven’t created yet?”