How to decide what to include in your notes

Before the days of computers, people used to collect all sorts of useful information in a commonplace book.

The ancient idea of commonplaces was that you’d have a set of subjects you were interested in. These were the loci - the places - where you’d put your findings. They were called loci communis - common places, in Latin, because it was assumed everyone knew what the right list of subjects was.

But in practice, everyone had their own set of categories and no one really agreed. It was personal.

Since the digital revolution, things have become trickier still. There’s no real storage limit so you could in principle make notes about everything you encounter. But no matter what software you use, your time on this earth is limited, so you need to narrow the field down somehow1.

But how, exactly?

You might consider just letting rip and collecting everything that interests you, as though you’re literally collecting everything.

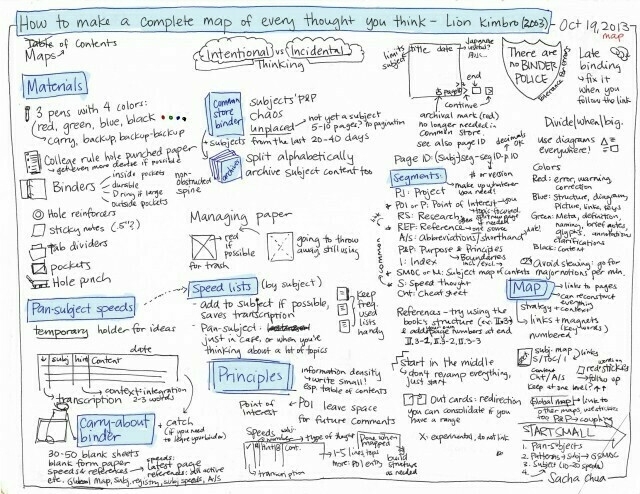

Lion Kimbro tried to make a map of every thought he had.

As time passes, you’ll notice that you haven’t actually collected everything because that’s completely impossible. Even Thomas Edison, the prolific inventor, wasn’t interested in absolutely everything, although he tried hard to be. If you do a bit of a stock-take of your own notes, you’ll see that, really, you gravitate towards only a few subjects.

These are your very own ‘commonplaces’.

From then on you have two choices.

- If you’ve enjoyed it so far, you can just keep doing what you’ve been doing, collecting all the things. Why not?

- But if you like, you could start doing it more deliberately. For example, at the start of a new year, you could say to yourself: In 2023 I seem to have been interested in a,b, and c. Now in 2024 I want to explore more about b, drop a, and learn about d and e.

You could create an index, with a set of keywords, and add page number references to show what subject each entry is about, and how they relate. Or not. Of course, it’s your collection of notes and you can do whatever pleases you. That’s the point.

Bower birds collect everything, but with one crucial principle.

Where I live we have satin bower birds.

The male creates a bower out of twigs and strews the ground with the beautiful things he’s found. Apparently this impresses the females. The bower can contain practically anything, and it really is beautiful. Clothes pegs, pieces of broken pottery, plastic fragments, bread bag ties, lilli pilli fruit, Lego, electrical wiring, string - even drinking straws, as in the photo above. The male bower bird really does collect everything. But what every human notices immediately is that every single item, however unique, is blue.

I enjoy collecting stuff in my Zettelkasten, my collection of notes, but like the bower bird I have a simple filter. I always try to write: “this interests me because…” and if there’s nothing to say, there’s no point in collecting the item. It’s just not blue enough.

See also:

- How to be interested in everything

- Don’t you need to start with categories?

- It’s tempting to place your notes in fixed categories

- To build something big start with small fragments

- Thoughts are nest-eggs: Thoreau on writing

- This article is adapted from a comment on Reddit

Images:

Sacha Chua Book Summary CC-by-4.0.

Peter Ostergaard, Flickr, CC NC-by 2.0 Deed

-

There are exceptions. A few people have tried to video their whole lives. And at least one person, Lion Kimbro, has tried to write down all their thoughts. But its not sustainable. ↩︎