Atomic Notes

-

Don’t build a magnificent but useless encyclopaedia

-

Document your journey through the deep forest

-

Avoid inert ideas

-

Converse about what really matters to you

-

Imagine, then build, new knowledge products

-

Where (and how) you go is more important than where you start from

-

An example

-

If you’re not sure what website feeds are, see IndieWeb: feed reader and how to use RSS feeds. ↩︎

-

Does the index box distort the facts?

-

Can you create coherent writing just from a pile of notes?

-

Perhaps you should keep your notes private

-

Make it flow

-

To create coherent writing, make coherent notes

-

Begin with fragments

-

From smaller parts build a greater whole

-

Join your work together

-

Do it seamlessly well

- If you’ve enjoyed it so far, you can just keep doing what you’ve been doing, collecting all the things. Why not?

- But if you like, you could start doing it more deliberately. For example, at the start of a new year, you could say to yourself: In 2023 I seem to have been interested in a,b, and c. Now in 2024 I want to explore more about b, drop a, and learn about d and e.

- How to be interested in everything

- Don’t you need to start with categories?

- It’s tempting to place your notes in fixed categories

- To build something big start with small fragments

- Thoughts are nest-eggs: Thoreau on writing

- This article is adapted from a comment on Reddit

-

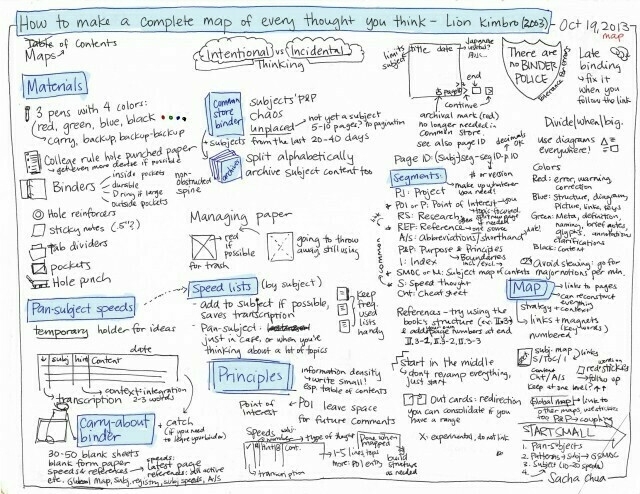

There are exceptions. A few people have tried to video their whole lives. And at least one person, Lion Kimbro, has tried to write down all their thoughts. But its not sustainable. ↩︎

-

Which way is up?

-

Try seeing the trees and the forest too

-

Hierarchy, heterarchy, homoarchy… am I just making these words up?

-

Get linking to get thinking

-

The key questions

-

What if I really just want a fixed structure?

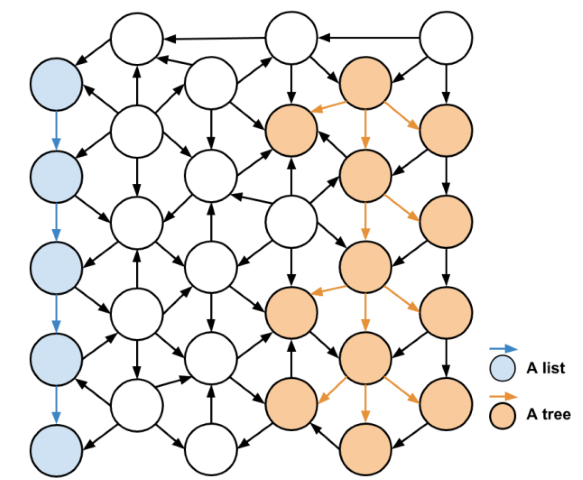

- A network of notes is a rhizome not a tree.

- Manuel Lima on The power of networks (it’s a cool video!)

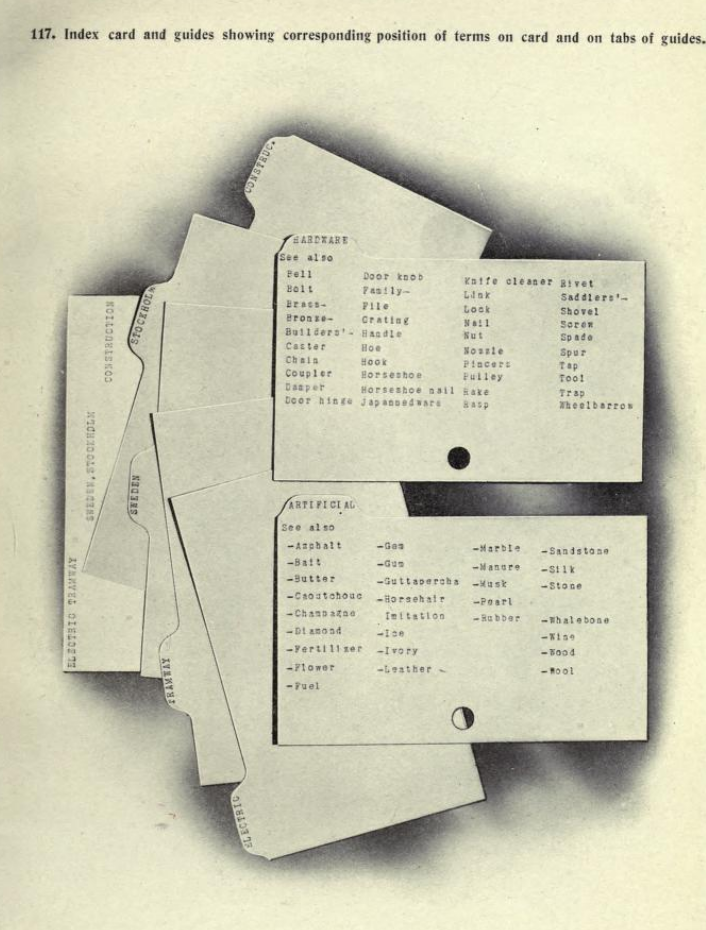

- Top image source: The Card System at the Office by J. Kaiser, 1908.

- Free-form note-making. In this mode, you start with no expectations and just make notes whenever something grabs you. This is great when you don’t yet know what you want to focus on. The risk is you try to read everything, only to discover it’s like drinking the ocean. Ars longa, vita brevis, so you’ll ultimately need to narrow down your field somehow.

- Directed note-making. In this mode, you already know, broadly, what interests you, for example, Richard Hamming’s 10-20 problems. So you make notes whenever something you read resonates with one of your predetermined interests. I used to think I was interested in everything, like Thomas Edison. But after writing notes on whatever took my fancy for a while, I observed that really, I kept revolving around a fairly limited set of concerns. So mostly these days I make directed notes, or else engage in the closely related purposeful note-making.

- Purposeful note-making. This mode is more focused still than directed note-making. Here you have a specific project in mind, such as a particular book or article you want to write, and so you make notes whenever your reading material chimes with what you want to write about. If there’s a risk to this kind of note-making, it’s that in your focused state, you’ll miss ideas that you might otherwise have found worth making notes about.

- N - what larger pattern does this concept belong to?

- S - what more basic components is this concept made of?

- E - what is this concept similar to?

- W - what is this concept different from?

-

you’ll write worthwhile notes that address your own questions and

-

this hook of curiosity will help you remember as you learn.

-

What does the medium enhance?

-

What does the medium make obsolete?

-

What does the medium retrieve that had been obsolesced earlier?

-

What does the medium reverse or flip into when pushed to extremes?

The card index system is ‘a thing alive’ - or is it?

Niklas Luhmann, the famed sociologist of Bielefeld, Germany, wrote of how he saw his voluminous working notes (his ‘Zettelkasten’) as a kind of conversation partner, which surprised him from time to time. But he wasn’t the first to suggest that a person’s notes might be in some sense alive.

At the end of the Nineteenth century there was a massive explosion of technological change which affected almost every aspect of society. People marveled at new invention after new invention and there was a tendency to see mechanical and especially electrical advances as somehow endowed with life. The phonograph, for example, was held to be alive and print adverts even claimed it had a soul.

How to start a Zettelkasten from your existing deep experience

An organized collection of notes (a Zettelkasten) can help you make sense of your existing knowledge, and then make better use of it. Make your notes personal and make them relevant. Resist the urge to make them exhaustive.

💬"At what point does something become part of your mind, instead of just a convenient note taking device?"

A question discussed with philosopher David Chalmers, on the Philosophy Bites podcast.

🎙️Technophilosophy and the extended mind

So much of this depends on what ‘the mind’ means. Meanwhile, we do seamlessly interact with our note-making tools, to achieve more than we could without them.

Give it, give it all, give it now

Mark Luetke shows how he uses a Zettelkasten for creative work (‘zines!)

“The goal here is to create an apophenic mindset - one where the mind becomes open to the random connections between objects and ideas. Those connections are the spark we’re after. That spark is inspiration.”

Atomic notes - all in one place

From today there’s a new category in the navigation bar of Writing Slowly.

‘Atomic Notes’ now shows all posts about making notes.

How to make effective notes is a long-standing obsession of mine, but this new category was inspired by Bob Doto, who has his own fantastic resource page: All things Zettelkasten.

The Atomic Notes category is now highlighted on the site navigation bar.

And if you’d like to follow along with your favourite feed reader,there’s also a dedicated RSS feed (in addition to the more general whole-site feed).1

But if there’s a particular key-word you’re looking for here at Writing Slowly, you can use the built-in search.

And if you prefer completely random discovery, the site’s lucky dip feature has you covered.

Connect with me on micro.blog or on Mastodon. And on Reddit, I’m - you guessed it - @atomicnotes.

See also:

Assigning posts to a new category with micro.blog

How to overcome Fetzenwissen: the illusion of integrated thought

It’s too easy to produce fragmentary knowledge.

One potential problem associated with making notes according to the Zettelkasten approach is Verknüpfungszwang: the compulsion to find connections. It may be true philosophically that everything’s connected, but in the end what matters is useful or meaningful connections. With your notes, then, you need to make worthwhile, not indiscriminate links.

Another potential problem is Fetzenwissen: fragmentary knowledge, along with the illusion that disjointed fragments can produce integrated thought.

Almost by definition, notes are brief, and I’m an enthusiast of making short, modular, atomic notes. Yes, this results in knowledge presented in fragments. And in their raw form these fragmentary notes are quite different from the kind of coherent prose and well-developed arguments readers usually expect. You can’t just jam together a set of notes and expect them to make an instant essay. So is this fragmentary knowledge really a problem for note-making? If so, how can determined note-makers overcome it?

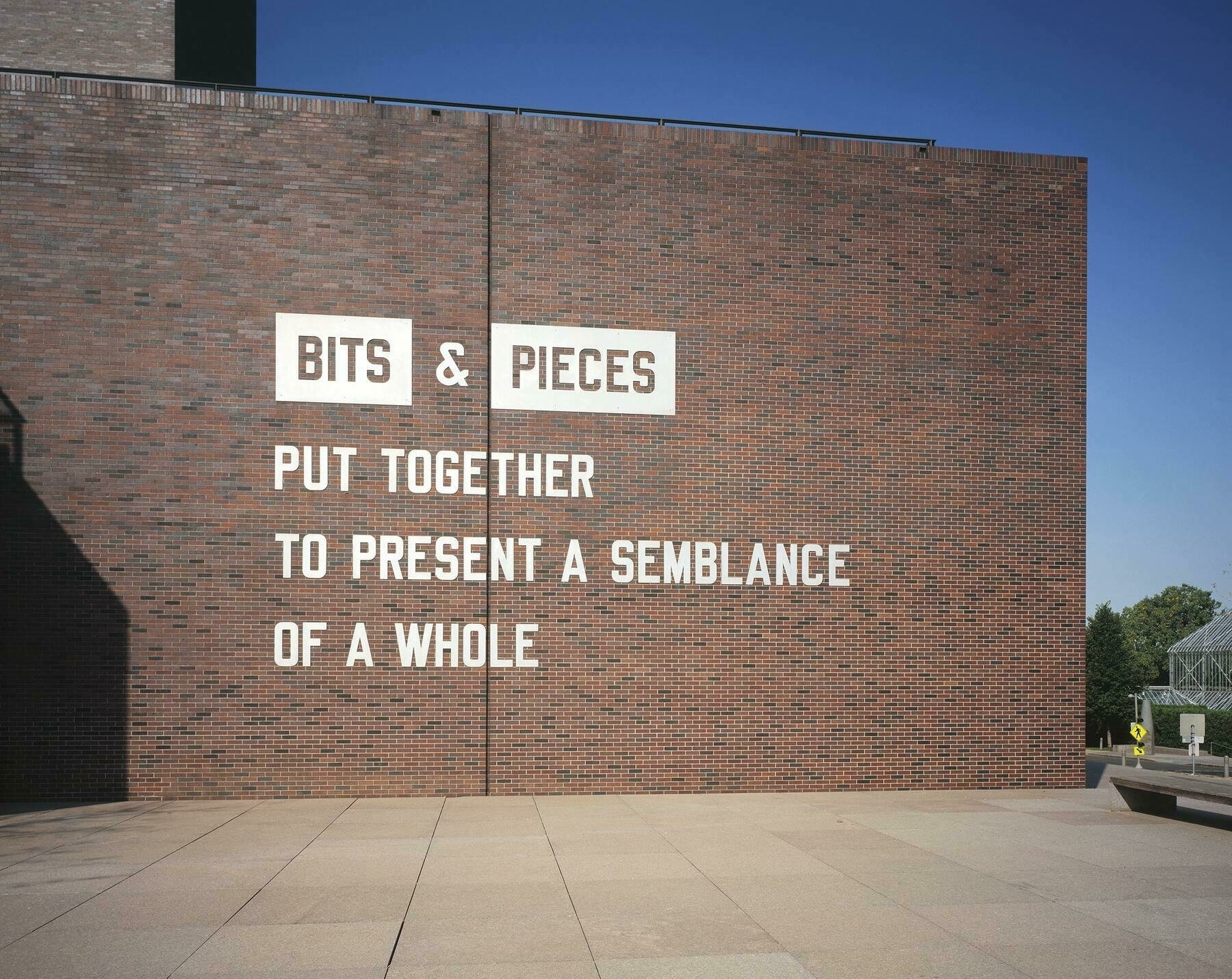

From fragments you can build a greater whole

Everything large and significant began as small and insignificant

This is my working philosophy of creativity and I’m trying to follow it through as best I can. Starting with simple parts is how you go about constructing complex systems.

“A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over, beginning with a working simple system”. — John Gall (1975) Systemantics: How Systems Really Work and How They Fail, p. 71.

Bits and pieces put together to create a semblance of a whole, by Lawrence Weiner

How to decide what to include in your notes

Before the days of computers, people used to collect all sorts of useful information in a commonplace book.

The ancient idea of commonplaces was that you’d have a set of subjects you were interested in. These were the loci - the places - where you’d put your findings. They were called loci communis - common places, in Latin, because it was assumed everyone knew what the right list of subjects was.

But in practice, everyone had their own set of categories and no one really agreed. It was personal.

Since the digital revolution, things have become trickier still. There’s no real storage limit so you could in principle make notes about everything you encounter. But no matter what software you use, your time on this earth is limited, so you need to narrow the field down somehow1.

But how, exactly?

You might consider just letting rip and collecting everything that interests you, as though you’re literally collecting everything.

Lion Kimbro tried to make a map of every thought he had.

As time passes, you’ll notice that you haven’t actually collected everything because that’s completely impossible. Even Thomas Edison, the prolific inventor, wasn’t interested in absolutely everything, although he tried hard to be. If you do a bit of a stock-take of your own notes, you’ll see that, really, you gravitate towards only a few subjects.

These are your very own ‘commonplaces’.

From then on you have two choices.

You could create an index, with a set of keywords, and add page number references to show what subject each entry is about, and how they relate. Or not. Of course, it’s your collection of notes and you can do whatever pleases you. That’s the point.

Bower birds collect everything, but with one crucial principle.

Where I live we have satin bower birds.

The male creates a bower out of twigs and strews the ground with the beautiful things he’s found. Apparently this impresses the females. The bower can contain practically anything, and it really is beautiful. Clothes pegs, pieces of broken pottery, plastic fragments, bread bag ties, lilli pilli fruit, Lego, electrical wiring, string - even drinking straws, as in the photo above. The male bower bird really does collect everything. But what every human notices immediately is that every single item, however unique, is blue.

I enjoy collecting stuff in my Zettelkasten, my collection of notes, but like the bower bird I have a simple filter. I always try to write: “this interests me because…” and if there’s nothing to say, there’s no point in collecting the item. It’s just not blue enough.

See also:

Images:

Sacha Chua Book Summary CC-by-4.0.

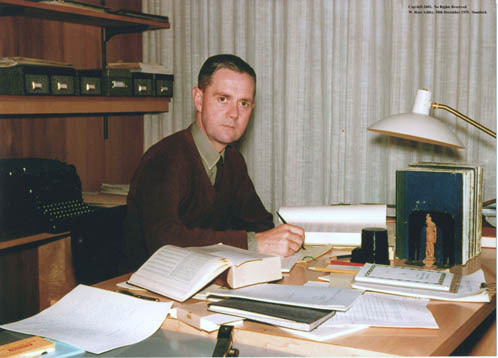

Peter Ostergaard, Flickr, CC NC-by 2.0 Deed

Does the Zettelkasten have a top and a bottom?

What does it mean to write notes ‘from the bottom up’, instead of ‘from the top down’?

It’s one of the biggest questions people have about getting started with making notes the Zettelkasten way. Don’t you need to start with categories? If not, how will you ever know where to look for stuff? Won’t it all end up in chaos?

Bob Doto answers this question very helpfully, with some clear examples, in What do we mean when we say bottom up?. I especially like this claim:

“The structure of the archive is emergent, building up from the ideas that have been incorporated. It is an anarchic distribution allowing ideas to retain their polysemantic qualities, making them highly connective.”

Ross Ashby's other card index

During the Twentieth Century many thinkers used index cards to help them both think and write.

British cyberneticist Ross Ashby kept his notes in 25 journals (a total of 7,189 pages) for which he devised an extensive card index of more than 1,600 cards.

At first it looks as though Ashby used these notebooks to aid the development of his thought, and the card index merely catalogued the contents. But it turns out he used his card index not only to catalogue but also to develop the ideas for a book he was writing.

Even the index is just another note

It’s tempting to place your notes in fixed categories

At some point in your note-making journey you’ll notice that quite a few people like to place their notes in fixed categories according to some scheme or other. The ancient method of commonplaces held that knowledge was naturally organised according to loci communis (common places). Ironically, no one from Aristotle onwards could ever agree on what the commonly-agreed categories were. Assigning your notes to categories is consistent with the ‘commonplace’ tradition, but that’s not what the prolific sociologist Niklas Luhmann did with his Zettelkasten, and furthermore it runs exactly counter to Luhmann’s claim in ‘Communicating with Slipboxes’, where he said:

“it is most important that we decide against the systematic ordering in accordance with topics and sub-topics and choose instead a firm fixed place (Stellordnung).”

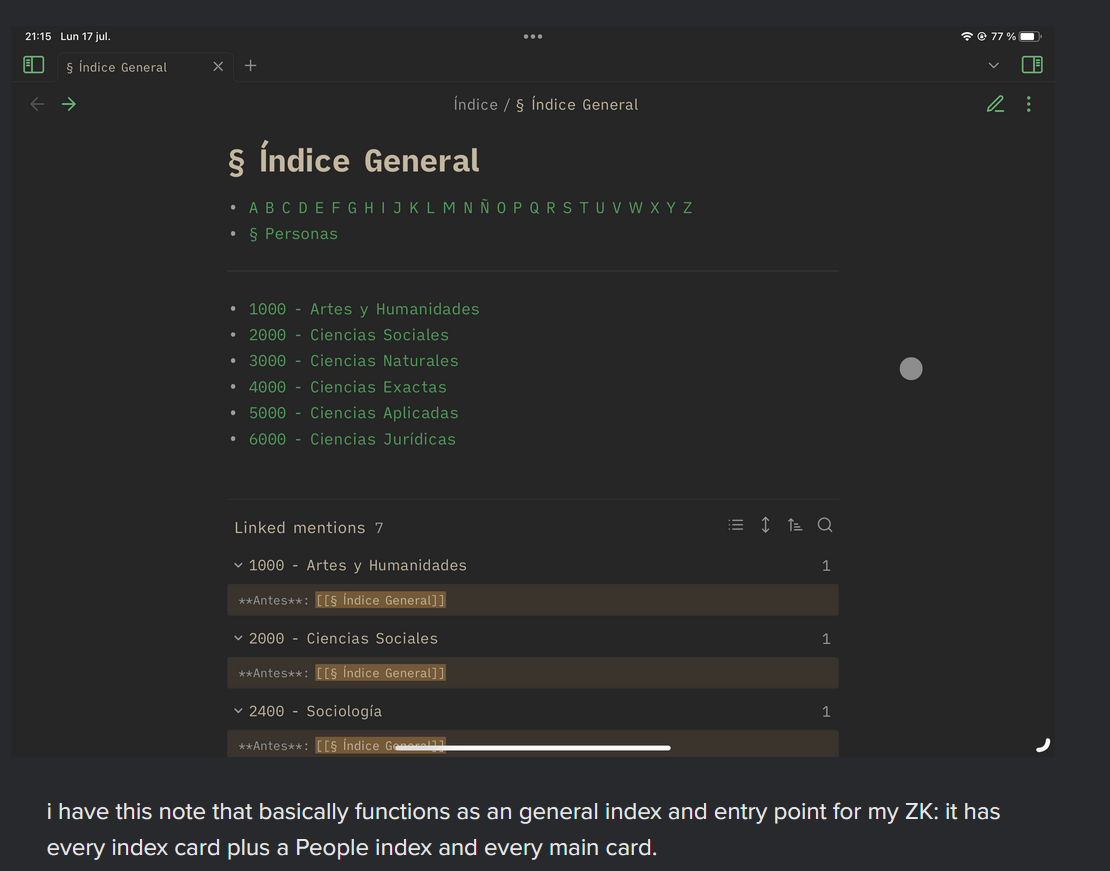

But there’s no need to despair, there is a way through the impasse! After all, what exactly is a subject or category? The subject or category index itself, it turns out, is nothing other than just another note. Here’s a real-life example:

“i have this note that basically functions as an general index and entry point for my ZK: it has every index card plus a People index and every main card.” - u/Efficient_Earth_8773

When everything’s a note, even the categories are just notes

Why does this matter? If even the index is just a note, then you haven’t constrained yourself with pre-determined categories. Instead, you can have different and possibly contradictory index systems within a single Zettelkasten, and further, a note can belong not only to more than one category, but also to more than one categorization scheme. Luhmann says:

“If there are several possibilities, we can solve the problem as we wish and just record the connection by a link [or reference].”

When even the index is just a note, a reference to a ‘category’ takes no greater (or lesser) priority than any other kind of link. This is liberating. Where a piece of information ‘really’ belongs shouldn’t be determined in advance, but by means of the process itself.

The Dewey Decimal System pigeonholes all knowledge, like cells in a prison.

Some people want an index, like folders in a filing cabinet, or subject shelves in the library. Well they can have it: just write a note with the subjects listed and make them linkable. Some people don’t want this, and they can ignore it. I personally don’t understand why you’d want to set up a subject index that mimics Wikipedia or the Dewey Decimal system, or even the ‘common places’ of old. I’m neither an encyclopedist, a librarian, nor an archivist. What I’m trying to do is to create new work. I want to demonstrate my own irreducible subjectivity by documenting my own unique journey through the great forest of thought. My journey is subjective, because it’s my journey. I’m pioneering a particular route, and laying down breadcrumbs for others to follow should they so choose. It’s unique, not because it’s original but because the small catalogue of items that attract me is wholly original. As film-maker Jim Jarmusch said:

“Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic.” (I stole that from Austin Kleon).

But that’s just me (and Luhmann).

Make just enough hierarchy to be useful

Having thought a bit about this I’m inspired now to sketch my own workflow, to see how it… flows. In general, I favour just enough data hierarchy to be viable - which really isn’t very much at all. I’m inspired by Ward Cunningham’s claim that the first wiki was ‘the simplest online database that could possibly work’. Come to think of it, this may be one of the disadvantages of the way the Zettelkasten process is presented: perhaps it comes across as more complex than it really needs to be. As the computer scientist Edsger Dijkstra lamented,

“Simplicity is a great virtue but it requires hard work to achieve it and education to appreciate it. And to make matters worse: complexity sells better.” - On the nature of Computing Science (1984).

If you must have hierarchies like lists and trees, remember that they’re both just subsets of a network.

Source: I don’t know. If you do, please tell me ;)

See also:

Three worthwhile modes of note-making (and one not-so-worthwhile)

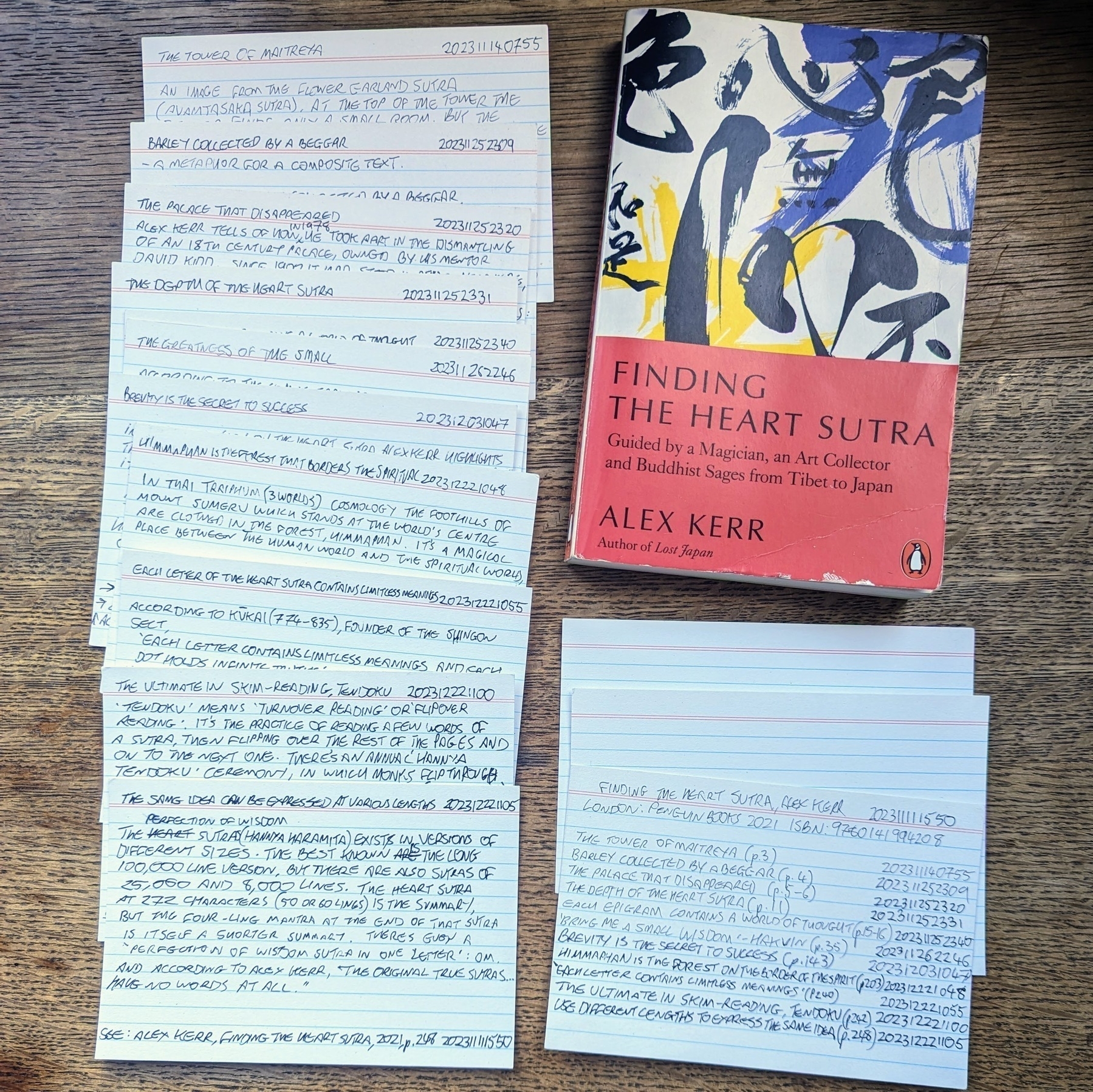

I finished reading Alex Kerr’s Finding the Heart Sutra on New Year’s Eve, so it just scraped into my reading for 2023. And while reading I made notes by hand, as I’ve done before. Although there aren’t very many notes (just eleven, plus a literature note that acts as a mini-index), they’re high quality, since I found the book very interesting.

I don’t mean I’ve written objectively ‘good’ notes. Rather, I mean the notes are high quality for my purposes. Everyone who reads with a pen in hand is an active reader, so the notes one person makes will be different - perhaps completely different- from the notes another person makes. In any case, no two readers read a book the same way.

Reflecting on this it seems to me there are at least three fruitful ways, or modes, of making notes while reading, as follows: Free-form, directed, and purposeful note-making.

Each of these note-making modes has its place, but in this particular case I was reading Finding the Heart Sutra with a very specific project in mind. So the notes I made were also quite specific. I imagine that someone else would be surprised by the notes I made, since they don’t really reflect the contents of the book. For instance, my notes are definitely not a summary of the book’s contents. Nor do they even follow the main contours of the book’s themes. Instead, I was making connections while reading with the main concerns of my own project. Each of my notes stands in its own right and could potentially be used in a variety of different contexts, but collectively, they make sense in relation to my own preoccupations. They fit into my own Zettelkasten, and no one else’s.

“Most great people also have 10 to 20 problems they regard as basic and of great importance, and which they currently do not know how to solve. They keep them in their mind, hoping to get a clue as to how to solve them. When a clue does appear they generally drop other things and get to work immediately on the important problem. Therefore they tend to come in first, and the others who come in later are soon forgotten. I must warn you, however, that the importance of the result is not the measure of the importance of the problem. The three problems in physics—anti-gravity, teleportation, and time travel—are seldom worked on because we have so few clues as to how to start. A problem is important partly because there is a possible attack on it and not just because of its inherent importance.” - Richard Hamming, You and Your Research. Sources: pdf; YouTube; Gwern.net.

If you want to know more about how to read a book, you could do worse than read How to Read a Book, by Mortimer Adler. It’s not the last word on the subject, but it’s a good starting point.

And it’s a warning against a fourth mode of note-making that I don’t advise: encyclopedic note-making. This is where you read a book and try to write a summary that will work for everyone. First, it’s hard work, and secondly, it’s probably already been done. If you open the link above you’ll see that the Wikipedia entry for How to Read a Book already includes a summary of the book’s contents. There are circumstances where the careful and complete summary is worthwhile, but I suggest you only start this task with the end - your own end - in mind.

If you have thoughts about making notes while reading, I’d be very interested to hear about it.

See also:

A note on the craft of note-writing

Learning to make notes like Leonardo

How to make the most of surprising yourself

How to be interested in everything

Thanks for reading. Why not check out my book, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters?

And to keep up to date, you can subscribe to the weekly email digest.

Publish first, write later

“Literature is perhaps nothing more complicated and glorious than the act of writing and publishing, and publishing again and again."

- Marcelo Ballvé, on the curious writing career of César Aira

César Aira on the constant flight forward

Argentinian author César Aira’s writing process is more about action than reflection. In a moment I’m going to share with you an extract from The Literary Alchemy of César Aira, an essay by Marcelo Ballvé, originally published in The Quarterly Conversation in 2008.

But before coming to the extract, I’ll just comment on David Kurnick’s claim in Public Books that Aira’s work is primarily about process:

“It is not in the least original to begin talking about César Aira’s work by recounting the technique that produces it. But it can’t be helped: Aira has made a discussion of his practice obligatory. To read him is less to evaluate a freestanding book, or a series of them, than to encounter one of the most extraordinary ongoing projects in contemporary literature.”

True, I’m not being at all original here, just cutting and pasting. Still…

Aira’s own Aleph

It’s as though through his writing Aira has found the basement in Buenos Aires that contains the entire universe in condensed form, the basement that features in Borges’s 1945 story “The Aleph”.

And having found that fabled basement, it’s as though Aira has taken on the persona of Carlos Argentino Daneri, the character in Borges' story whose life’s obsessive goal is to write a poetic epic describing each and every location on Earth in perfect detail.

But instead of taking the find seriously, Aira parodies it. Everything is here: and what do you know? None of it makes sense! Or, perhaps instead of parodying “The Aleph”, he takes it completely seriously: Why not write about it, about all of it? What then? In an interview in 2017 for the New Yorker, Aira said: “I am thinking now that maybe . . . maybe all my work is a footnote to Borges.”

Of course I’m not just cutting and pasting. I’m writing too. Aira also inspires my own writing process. His example inspires me to choose my own race - and finish it.

One of my role models is the Argentinian author César Aira. He’s written a very large number of novels and novellas (at least 80 - around two to five per year since 1993), published by a variety of presses. That’s a lot of races and a lot of finish lines crossed.

Now here’s Marcelo Ballvé on Aira’s unique writing process.

According to Aira, he never edits his own work, nor does he plan ahead of time how his novels will end, or even what twists and turns they will take in the next writing session. He is loyal to his idea that making art is above all a question of procedure. The artist’s role, Aira says, is to invent procedures (experiments) by which art can be made. Whether he executes these or not is secondary; Aira’s business is the plan, not necessarily the result. Why is procedure all-important? Because it is relevant beyond the individual creator. Anyone can use it.

Aira’s procedure, which he has elucidated in essays and interviews, is what he calls el continuo, or la huida hacia adelante. These concepts might be translated into English as “the continuum,” and a “constant flight forward.” Editing is an abhorrent idea in the context of Aira’s continuum. To edit oneself would be to retrace one’s steps, go backwards, when the idea is to always move forward. To judge yesterday’s writing session, to censor a lapse into the absurd or the irrational, to revive a character your work-in-progress sent tumbling over a cliff—all of these actions go against Aira’s procedure. Instead, the system prioritizes an ethic of creative self-affirmation and, I would say, optimism. To labor to justify previous work with more strange creations that in turn establish the need for ever more artistic high-wire acts in the future—this is the continuum, the high-wire act the artist must perform when he refuses to submit to any rule that is not his autonomously chosen procedure. It is an act performed with deep abysses yawning to each side of him—conformity, market pressures, conventionality, self-repression of all kinds . . . In other words, Aira’s literary career, embodied in each of his 63 novels, is a reckless pursuit of artistic freedom.

Aira says that when he sits down to write his daily page or two, he writes pretty much whatever comes into his head, with no strictures except that of continuing the previous day’s work. (The spontaneous feel of his stories would seem to back up this claim, but I’ve always asked, can anyone write as well as Aira does while simply letting the pen ramble?)

True, his books are very short. Aira says in interviews that he’s often tried to make his novels longer, but they seem to come to a natural rest at around the 100-page mark. Technically, much of what Aira has written would have to be classified in the novella category, but it’s hard to classify Aira’s work within any genre, be it story, novel, or novella. In my mind, Aira’s creations are something different altogether. They are stories, pure and simple, which Aira has managed to ennoble by seeing them into publication in the form of a single book. What he has done is put stories into circulation as objects, which is a defiant feat when seen in the context of a global literary market that demands hefty, sprawling, “big” novels.

The key to Aira’s curious career, I think, is to be found in his conception of literature as something with more affinities to the realm of action than the inner world of reflection. Literature is perhaps nothing more complicated and glorious than the act of writing and publishing, and publishing again and again. Editing is dispensable, so is the search for the “right” publisher. (Aira publishes seemingly with whomever shows any interest in his manuscripts; at least a dozen publishers, most of them small independents, in Argentina alone.) The idea seems to be: publish first and ask questions later…In fact Aira’s mentor, the deceased Argentine poet and novelist Osvaldo Lamborghini had a saying: “Publish first, write later.”

Extracted from The Literary Alchemy of César Aira, by Marcelo Ballvé. The Quarterly Conversation

César Aira’s main publisher in English is New Directions. They’ve published about 21 of Aira’s works in translation, while And Other Stories has published another half-dozen.

Now read: Choose your own race

How to make the most of surprising yourself

Your collection of linked notes, your Zettelkasten, isn’t a ‘second brain’, as though it were separate from your first, actual brain. Rather it is part of your extended mind, which your brain creates constantly by co-opting its wider environment into its own processing activity. Brain and environment together create mind. In the case of the Zettelkasten it’s a very deliberate extension of the brain, with a few simple but powerful generative rules.

One of the interesting features of this deliberately extended cognitive tool is its ability to present you with surprises. Reading through old notes, for example, you may be surprised that you ever wrote this. And re-reading your work in the light of new information, you may have new flashes of inspiration or see new connections that weren’t previously visible. Or perhaps the juxtaposition of two seemingly unrelated notes will prompt you to create a third, which contains an entirely new idea.

In this sense, your notes become a kind of conversation partner, reminding you of what you once thought, and even challenging you to go further. It’s a living thinking environment, an ever-evolving ‘connectome’, which sometimes appears to have a life of its own.

Why not surprise yourself?

Philosopher Andy Clark is quite well known for claiming that the human mind extends beyond the brain, and that “human brains spawn and maintain extended human minds”.

In a podcast interview with Sean Carroll, he recommends artificially curating environments in which we can surprise ourselves. This temporary increase in uncertainty, he claims, reduces prediction error in the long term.

“it looks as if very often, the correct move for a prediction-driven system is to temporarily increase its own uncertainty so as to do a better job over the long time scale of minimizing prediction errors, and that looks like the value of surprise, actually, and that we will… I think we artificially curate environments in which we can surprise ourselves. I think, actually, this is maybe what art and science is to some extent, at least, we’re curating environments in which we can harvest the kind of surprises that improve our generative models, our understandings of the world in ways that enable us to be less surprised about certain things in future.”

Clark refers to the work of Karin Kukkonen, a literary scholar who has applied the idea of predictive processing to literature. This reminded me of Steven Johnson’s suggestion in his book, Farsighted that a good novel is a decision-making simulation. He extolls the sophisticated decision-making conundrums of the characters in George Eliot’s Middlemarch, over the simpler black-and-white decisions of Charles Dickens' characters.

So perhaps the surprise function of the Zettelkasten is more useful than at first appears. It isn’t merely an aid to memory, or a handy conversation partner, or a writing prompt. On Clark’s account, it may also enable precisely the kind of surprises we need and can learn from in order to understand the world better.

Of course, we constantly encounter surprises in everyday life, and sometimes learn from them too. But viewed through the ‘predictive, extended mind’ lens, the Zettelkasten presents a precise, controlled and deliberate laboratory for cultivating such a learning process.

I wonder how your notes have surprised you. Please let me know.

Some resources

Andy Clark on the Extended and Predictive Mind - [Sean Carroll’s Mindscape: Science, Society, Philosophy, Culture, Arts, and Ideas] (https://www.preposterousuniverse.com/podcast/2023/04/27/235-andy-clark-on-the-extended-and-predictive-mind/)

Clark, Andy. 2022. Extending the Predictive Mind, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, DOI: 10.1080/00048402.2022.2122523

Johnson, Steven. 2018. Farsighted : How We Make the Decisions That Matter the Most. New York: Riverhead Books an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

Kukkonen, Karin. 2020. Probability Designs: Literature and Predictive Processing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780190050962

See also

A network of notes is a rhizome not a tree

Learning to make notes like Leonardo

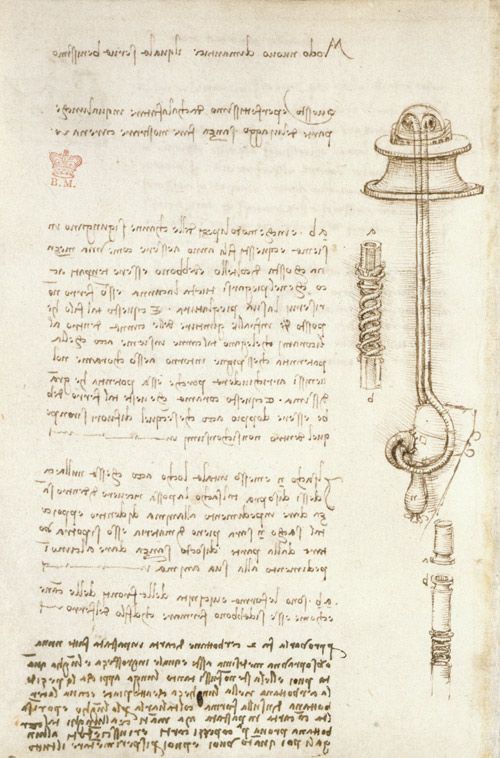

Leonardo wrote on loose sheets of paper

The Codex Arundel, a notebook of Leonardo Da Vinci, is not what it first appears. It isn’t a notebook that Leonardo used. For the man himself it wasn’t a notebook at all. It’s a collection of individual notes, bound for convenience only after his death. The British Library webpage observes:

“The structure of the notebook reveals that it was not originally a bound volume. It was put together after Leonardo’s death from loose papers of various types and sizes, some indicating Leonardo’s habit of carrying smaller bundles of notes to document observations outdoors.”

He wasn’t the first to adopt this habit. Beginning in the Fourteenth century it had become something of a fashion for Italians to create their own ’zibaldone’, a hodgepodge of notes on diverse subjects. Leonardo wrote of his notes:

“This is to be a collection without order, drawn from many papers, which I have copied here, hoping to arrange them later each in its place, according to the subjects of which they treat.”

The same is true of the Forster Codices, in the care of the Victoria and Albert Museum: they weren’t originally codices (books), but unbound notes.

“Leonardo probably worked on loose sheets of paper (bought at one of Milan’s many stationers' shops), which he carried about with him to record his observations. His papers were at some stage folded into booklets and later bound, possibly under the ownership of the Spanish sculptor Pompeo Leoni (1533 – 1608).” (https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/leonardo-da-vincis-notebooks)

Many of the notes in the Codex Arundel were written in 1508, but they span most of Leonardo’s career.

The notes cover a very wide range as well as references to many different subjects. They include sketches of a mechanical organ and of an underwater breathing apparatus, There are notes and diagrams on mechanics, lists of proverbs and riddles, sketches on bird-flight, a household inventory, notes on optics and mirrors for producing heat, calculations on balances and weights, a plan for an urban quarter, and for a complete city, notes on the acoustics of drums and wind instruments, notes on river dynamics and on geometry, and a sketch of a cockleshell.

Leonardo Da Vinci - master of making notes

Here’s the German scholar Hektor Haarkötter, writing about the note-making expertise of Leonardo Da Vinci:

“Leonardo is the early master of the note [Nottizettel]. Today da Vinci is famous as an artist and painter, inventor and designer. However, he was not very productive as a public artist. Only about fifteen paintings that can be proven to have been created by him have survived, some of them in very poor condition or never completed. Leonardo da Vinci was really productive, however, in the privacy of his writing. He left behind over 10,000 sheets, drafts, scraps, snippets, sketches, papers, pages and slips of paper. (Many have been transcribed in Theodor Lücke, Leonardo da Vinci. Tagebücher und Aufzeichnungen. Leipzig, Paul List Verlag, 1953)

And this is only the part of his many records that have come down to us. Through his papers we know of other ledgers, notebooks, and codices, but they have disappeared, been scattered, torn apart, sold off, or in one way or another through the course of time, simply destroyed. How large the number of those records is of which we have no, well, note, is incalculable.

Already in Leonardo’s work all the characteristics of the note [Nottizettel] as a private medium are visible. He wrote in a code so that unauthorized eyes could not have read his notes. The universality of writing materials and forms of writing corresponded the universality of the subjects. From word lists and shopping wishes to technical drawings and philosophical notes to obscene and pornographic sketches. None of them was intended for the public, and the Renaissance master never published a book. He would hardly have been able to do so, he admitted to himself in his notebooks, which today are traded at astronomical prices at auctions, but which themselves lost an overview of his records.

What remains?

The amazing thing about the inconspicuous medium of notes is that from a hodgepodge of notes in the writing practice of writers and scientists, a completed book can emerge in the end. However we must not forget that, as a rule, only a small part of the notes, as a preliminary stage, finally ends up in the work. The larger part of such paralipomena [supplementary material, literally ‘things omitted’] remains, is never used, is hardly ever read again, and is often discarded and thrown away. Or the notes end up in the archives, where they are preserved as cryptic manuscripts, in worm-eaten folders or as messy single sheets, where they can enjoy the security of all basement magazines, never again to be viewed by human eyes. Notes are communicants after all without communicating. The path to the finished book is paved with media corpses.”

Source: Hektor Haarkötter, «Ich notiere, also bin ich» Notizen als Medien des Denkens Passim 28 (2021) Bulletin des Schweizerischen Literaturarchivs, p.4-5. Available at: <www.nb.admin.ch/snl/de/ho…> Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator and a bit of imagination.

What can we learn from Leonardo’s approach to making notes?

Write everything down

Make notes. you never know when you’ll invent a diving mechanism, or a flying machine, or who knows what else? Toby Lester, author of Da Vinci’s Ghost, claims, “Whenever something caught his eye he would compulsively open a small notebook that he wore hanging from his belt and begin sketching furiously, with almost mind-boggling virtuosity. He loved his tiny sketchbook and recommended that all serious artists carry one.” “These things should not be rubbed out,” wrote Leonardo, “but preserved with great care, for the forms and positions of objects are so infinite that the memory is incapable of retaining them”. Leonardo plainly wrote (and drew) in order to think - and you can too.

Use your memory too

Don’t expect your note system to remember things for you. There is a view that writing helps you to remember. But Hektor Haarkötter calls this ‘a myth of the media’. “In fact,” he says, “there is hardly a more effective way to erase a thought from memory than to write it down. The problem of remembering is not solved by taking notes, but only delegated, namely from “What did I want to remember?” to “Where did I write it down?” And the larger the volume of notes, the smaller the probability of finding a specific note again.” So making a note is primarily the act of thinking itself, not a primarily a way to remember what you thought.

Do what works for you

Loose leaf pages worked for Leonardo, and he wrote thousands of them. He had a system that enabled him both to think and to capture his thoughts. Don’t wait for the ideal system to appear, when an OK one will do. And don’t over-complicate things. He didn’t have a Moleskine notebook, or Obsidian software. He just wrote.

Don’t put off the organisation for another time

Don’t put it off, because that day may never come.

Leonardo intended “to arrange them later each in its place, according to the subjects of which they treat”, but as far as we can tell, he never did. This is possibly a reference to the then popular practice of arranging notes in ‘loci communis’, or commonplaces - so called because there were several different standard systems of thematic arrangement by category. He didn’t get round to it. And later editors didn’t have much idea of what order to put his notes after he was gone. Who knows what he might have finished if he’d been a bit more organised at the outset. Don’t put off the organisation of your notes, because it will probably never happen.

Publish, by any means necessary

Notoriously, Leonardo hardly finished anything. Some of this, such as the unfinished painting now known as Mona Lisa, may have been deliberate. But on his death, Leonardo left his notes to his faithful pupil Francesco Melzi, who then left them to his son. The son didn’t value them at all and abandoned them to molder in an attic, so it’s amazing any of these now priceless notes survived at all. In fact the reason Leonardo is best known as an artist, which was not his main occupation (in 1482 he put at the very bottom of his resume for the Duke of Milan, “also I can do in painting whatever may be done”), is that the notes were effectively lost for generations and only really came to attention in later centuries. Don’t put off the publishing of your knowledge. Your pupils' children might not follow your instructions any more than Leonardo’s did. Share what you know with others. Don’t expect it to outlive you. Seize the day. You might think you’re no Leonardo. That’s right. You’re not. You are you, and that’s exactly what the world needs.

Furthermore, it’s so much easier to publish these days than it was at the time of Leonardo. There’s hardly any excuse not to press ‘send’.

There might just be a better system

I hesitate to try to improve on arguably the greatest genius of all time, but with the greatest presumption, here goes. Leonardo himself called his notes ‘a collection without order’, and perhaps a modicum of order might heave helped him. The system he never got around to using was that of ‘commonplaces’, extremely widely used during the Renaissance and for centuries after. The idea was that you’d catalogue your notes according to a more-or-less standard set of locations (i.e. common places). There are a few problems here.

First, it’s hard and uninteresting work to catalogue all your thoughts into predetermined folders like this. Perhaps that’s why Leonardo didn’t do it. Maybe it was just not important enough.

Second, even if you do want to file your notes, it’s not universally agreed what the folder names should be. Through the ages there have been numerous attempts to design a standard set of commonplaces, and none of them have stuck. One such is the Dewey Decimal System, often used for cataloguing library subjects. Not even all the libraries follow this particular system. Wikipedia has a list of ‘main topic classifications’, too. Though you might not know this, you probably haven’t suffered from your ignorance on this matter. To the ordinary Wikipedia user, it doesn’t really seem to make much difference.

Third, keeping your ideas in the categories within which they were formed tends to limit innovation and re-combination. For example, a folder of notes labelled ‘psychology’ doesn’t really tell you much and it keeps your psychology ideas artificially separated from your thoughts on art, or sport, or jokes. In fact, any categories tend to damp down the creative spark. Perhaps that’s why Leonardo’s ‘collection without order’ worked for him.

More resources

The Codex Arundel is at the British Library and online.

David Kadavy has a great podcast episode about Leonardo: Leonardo Mind, Raphael World – Love Your Work, Episode 290 Ironically, Kadavy sees Leonardo as ‘the greatest procrastinator who ever lived’. It’s ironic because, well, it’s Leonardo.

Hektor Haarkötter’s book on notemaking includes more on Leonardo as well as a host of other characters, but Notizzettel is currently only published in German.

And if you’ve read this far, you’ll love Gillian Hess’s Substack blog, Noted. She has already written plenty about Leonardo, which you can read by subscribing.

Meanwhile, on this site, I’ve also written about Aby Warburg’s compulsion to make notes, and about Ted Nelson’s evolutionary file list, and about the writing process of Henry Thoreau - and probably lots more about Zettelkasten I’ve forgotten about.

—

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now.

And if you found this article interesting you might like to sign up to the Writing Slowly weekly email digest. You’ll receive all the week’s posts in that handy email format you know and love.

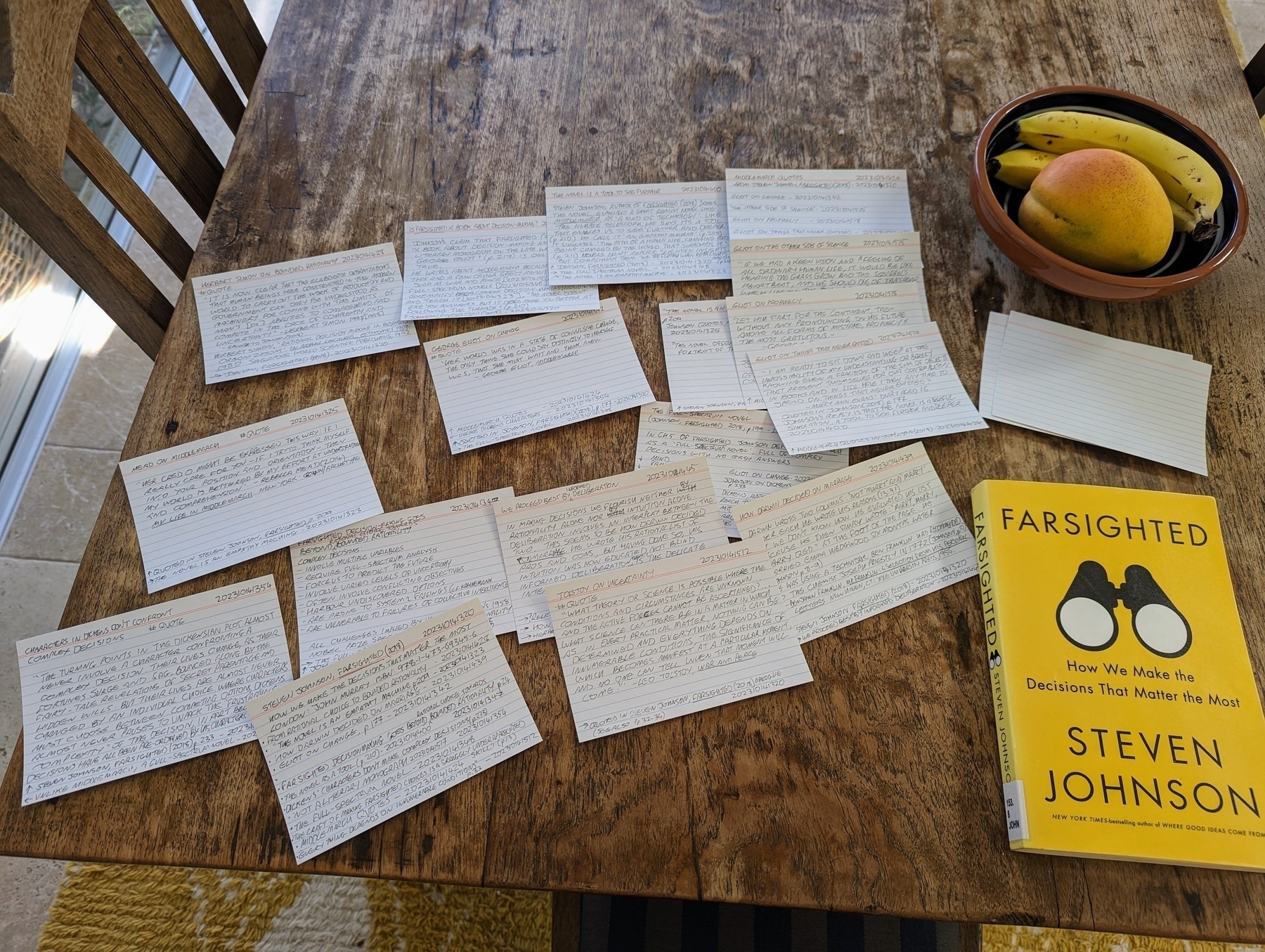

Finished reading: Farsighted by Steven Johnson 📚

Wrote 17 notes in 2 hours, and enjoyed doing it by hand. Realised this book is as much about novels - especially Middlemarch - as it is about making decisions. And that a good novel is a decision-making simulator. #Zettelkasten #Notemaking

A note on the craft of note-writing

An fairly new article from Brazil caught my eye, on note-writing as an intellectual craft. It highlights the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann’s note-making process (he put his many linked notes in a Zettelkasten - an index box).

Cruz, Robson Nascimento da Cruz, and Junio Rezende. “Note-writing as an intellectual craft: Niklas Luhmann and academic writing as a process.” Pro-Posições 34 (2023).

<doi.org/10.1590/1…>

https://www.scielo.br/j/pp/a/L7gmq6W7bvzgn984hSJ94

Abstract: "Despite numerous indications that academic writing is a means toward intellectual discovery and not just a representation of thought, in Brazil, it is seen more as a product of studies and subjects than an integral part of university education. This article presents note-taking, an apparently simple and supposedly archaic activity, as a way through which academic writing is eminently oriented towards constructing an authorial thought. To this end, we discuss recent findings in the historiography of writing that show note-taking as an essential practice in the development of modern intellectuality. We also present an emblematic case, in the 20th century, of the fruitful use of a note-taking system created by German sociologist Niklas Luhmann. Finally, we point out that the value of note-taking goes beyond mere historical curiosity, constituting an additional tool for a daily life in which satisfaction and a sense of intellectual development are at the center of academic life."

If you live your life in chunks, what size should they be?

Life tends to be lived in chunks. Hours, days, weeks, months, seasons, years - these are familiar if slightly artificial concepts. But what’s the best-sized chunk of life to focus on? Some would advise living in the moment, by which they don’t really mean the 86,400 seconds that are available in a single day. They effectively mean no chunks at all (or infinite chunks, perhaps).

Reading an article on why you should divide your life into semesters reminded me that I’ve already come across this idea in the shape of the book The Twelve Week Year. I actually bought The Twelve Week Year for Writers, which I’ve skimmed but haven’t read properly yet. I’d like to have a structure to my year that’s more than just “get through it”. But I’m daunted by the thought of needing something concrete to show for my time spent on earth. What did you achieve in your chosen chunk of life? This question won’t be answered by heartbeats or breaths, by sunsets or swims. It would be OK maybe if it could be answered with dollars, but that’s not really acceptable either. It’s too soulless. The question, what did you achieve? needs actual achievements. It needs productivity of the sort I’m not very available for.

@visakanv says “the meandering mind is a feature not a bug”. Why can’t I accept this? Perhaps because I keep putting myself in situations where the meandering mind is a bug not a feature?

I can just about manage to write a short note like this. And then another one… and so on. Austin Kleon calls this “Sisyphus mowing the lawn”. And indeed, I’m happy writing my short notes. If I can’t manage to organise my life into semesters, perhaps I can organise it into atomic notes - the shortest possible viable writing session.

I saw on the zettelkasten.de forum that some members log their note-making productivity on a 10-day rolling tally. One person has written 16 notes in ten days, another has written 33.

They are inspired, as am I, by Sonke Ahrens' exhortation to work as is nothing counts other than writing (well, some of them are).

"If writing is the medium of research and studying nothing else than research, then there is no reason not to work as if nothing else counts than writing.

Focusing on writing as if nothing else counts does not necessarily mean you should do everything else less well, but it certainly makes you do everything else differently.

Even if you decide never to write a single line of a manuscript, you will improve your reading, thinking and other intellectual skills just by doing everything as if nothing counts other than writing."

I’d like to know what kinds of time you find yourself dividing your life into. Do you mainly live in days, or mainly in hours, or perhaps weeks? Do you instead devote yourself to living in the moment? If so, which moment?

#reading

How to connect your notes to make them more effective

A linked note is a happy note

A great strength of the Zettelkasten approach to writing is that it promotes atomic notes, densely linked. The links are almost as valuable as the notes themselves, and sometimes more valuable.

But once you’ve had an idea and written it down, what is it supposed to link to? Is there a rule or a convention, or do you just wing it?

How are you supposed to make connections between your notes when you can’t think of any?

When I started creating my system of notes I didn’t know how to make these links between my atomic ideas, and this relational way of working didn’t come naturally to me. I would just sit there and think, “what does this remind me of?” Sometimes I’d come up with a new link, but more often than not, I didn’t. The problem is, the Zettelkasten pretty much relies on links between notes. An un-linked note is a kind of orphan. It risks getting lost in the pile. You wrote it, but how will you ever find it again? And if you do somehow stumble upon it again, it won’t really lead anywhere, because you haven’t related it to anything else.

Fortunately, there are some helpful ways of coming up with linking ideas that can really aid creative thinking and unlock the power of connected note-making.

Make a path through your notes with the idea compass

Niklas Luhmann, the sociologist who famously (to nerds) kept a Zettelkasten, didn’t exactly say this, but each atomic note already implies its own series of relations. Each note can be extended by means of the idea compass - a wonderful idea of Fei-Ling Tseng, as follows:

Notice how the first two questions promote a tree-like hierarchical structure, with everything nested in everything else, while the second two questions promote a fungus-like anti-hierarchical structure, with links that form a rhizome or lattice. Alone, the former structure is too rigid and the latter is too fluid. But put them together and they can be very powerful. The genius of the Zettelkasten system is that it absorbs hierarchical knowledge networks into its overall rhizomatic structure, without dissolving them, and allows new structures to form (Nick Milo helpfully calls these ‘maps of content’).

Find the larger pattern

Each atomic idea might be thought of as part of a larger pattern. In a sense, every note title is just an item in a list that forms a structure note at a level above it. Say I write a note on ‘functional differentiation’. I realise that this is just one component of a structure note that also includes ‘social systems’, ‘communication’, ‘autopoeisis’ and so on. I write this list, call it ‘Niklas Luhmann - key ideas’, and link it to my existing note. Now I have some ideas for some more notes to write. But will I write them all? No - I’ll only pursue the thoughts that actually interest me, or seem essential. The rest can wait for another day. Actually, I’m suddenly intrigued by what you could possibly have instead of functional differentiation (i.e. what is this note different from?), so I write a new note called ‘pre-modern forms of social structure’ - and link it back to my ‘functional differentiation’ note.

Look for the basic components

Going even further, the atoms, which seemed to be the smallest unit, turn out to be made of sub-atomic particles and so on, all the way down to who knows what (well, particle physicists might know, but I don’t). That means each atomic idea is really just the title of a structure note that hasn’t been written yet. So I take a new note and write: ‘Functional differentiation - the key points’. I imagine this new structure note to be like a top-ten list of important factors, each one ultimately with its own new note - but I’m not going to force myself to write about ten things that don’t matter, just what I find interesting.

When making links, trust and follow your own interest

It’s really important that you don’t try to answer all four questions with a new link. You’re not creating an encyclopedia. Instead, you should only make the connections that actually matter to you. The trace of your own inquisitiveness through the material is, in itself, important information. If it doesn’t matter to you, don’t write about it! Since the notes are atomic, and the possible links increase exponentially (?) the possibility space you are opening up is almost infinite and it can feel overwhelming. So just go with the flow. The key is to find your own curiosity and run with it. That way (as I’ve said before):

That’s what I’ve been doing this morning. At no point have I stopped to think “what shall I write next?” In this sense, the Zettelkasten is a kind of conversation partner. Niklas Luhmann said he only ever wrote about things that interested him. This seems unlikely until you try it for yourself.

And if you keep asking yourself these questions, you’ll find that over time the linking starts to come naturally. It will be increasingly obvious to you what relationships matter. The questions in the idea compass will become intuitive and fade into the background. Well, that’s my experience, but YMMV.

Apply a framework that intrigues you

Another way of making connections, besides the idea compass, is to apply a conceptual framework (or mental model) that interests you - and see where it leads. Here’s an example: Marshall McLuhan’s tetrad of media effects.

The idea here is that any new technology changes the whole landscape or ecology, by bringing some features into the foreground and pushing others into the background. It’s called a tetrad because there are four questions to ask of a new technology:

(This really clicked for me when I puzzled over why my kids don’t use smart phones for talking to people. It seemed crazy to me, but then I looked at question 3 and realised the new technology had retrieved asynchronous communication, which the telephone had previously made obsolete. But I digress.)

Anyway, I’m suggesting you might be able to take these four questions and ask them of the ideas in your notes. For each atomic note: what does this idea enhance, make obsolete, retrieve, or reverse?

Another simple but powerful example is Tobler’s law: “I invoke the first law of geography: everything is connected to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things”. What would it be like if you made everything about physical location?

It’s important to say these are just examples, and they may not work for you. Nevertheless, you may be able to think of frameworks from within your own line of work that allow you to ask a similar set of questions about your ideas. In my experience these frameworks are everywhere and yet are quite under-used.

This article is a lightly edited version of a Reddit comment.

You might also like to read about how a network of notes is a rhizome not a tree.