The Dance of Joyful Knowledge: Inside Georges Didi-Huberman's Monumental Note Archive

People sometimes ask, “who these days uses Zettelkasten-style hand-written notes to produce significant work?” There are literally thousands of examples from before the digital age (Leonardo for example), but what of today? Isn’t this kind of thing pretty much obsolete?

No, it’s not obsolete. I’m happy to say the practice is still very effective.

Georges Didi-Huberman (Wikipedia) is a prolific French art historian and philosopher who has written more than sixty books.

He works in and beyond the tradition of cultural luminaries such as Aby Warburg and Walter Benjamin, so it’s no surprise that like them he keeps his own massive collection of working notes.

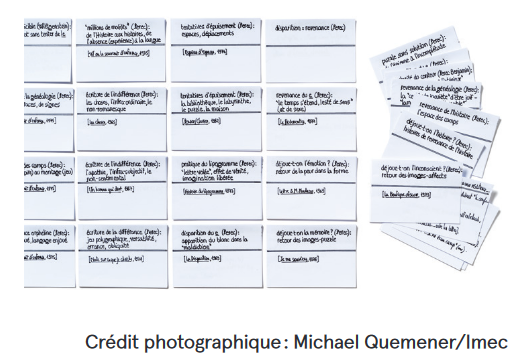

How many? Well, a recent exhibition was based on “his immense working file, begun in 1971, comprising more than 148,000 notes” (“son immense fichier de travail, commencé dès 1971, composé de plus de 148 000 fiches”).

And his process?

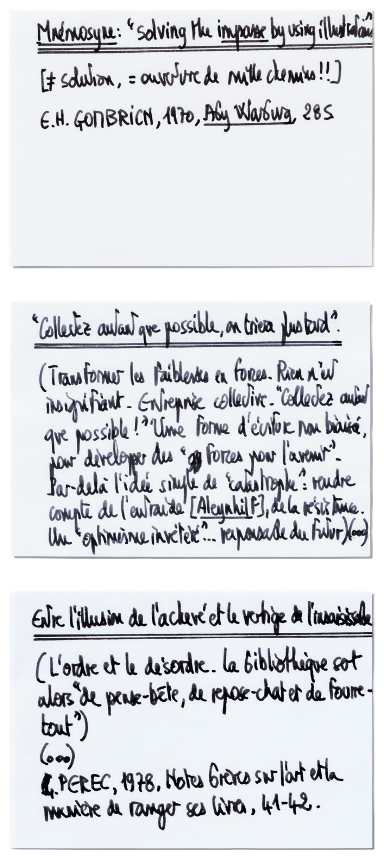

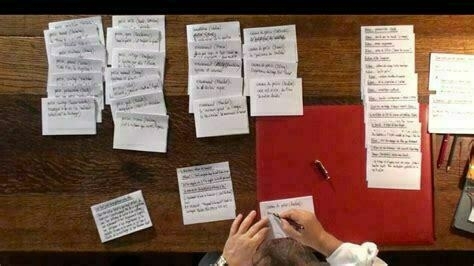

“To summarize, I would say that the first work is slow, modest, obsessive: it is the creation and accumulation of cards in confrontation or dialogue with certain texts or certain images. The second is fast, exhilarating, joyful, made of discoveries: it is the reassembly of the cards, like a successful card game, on a vast table where the layout of the cards allows one to visualize a large number of them synoptically and to see unexpected constellations emerge. The third work must be rhythmic or musical: it is the writing itself, the handwriting on the entire blank sheet.

As soon as there was a box, there were other boxes and other boxes still. The file is a tool for memorization, a technical prosthesis for thought that allows one to forget many cumbersome, even paralyzing, things. But we must know how to put an end to obsessive activity and the love of repetition, in order to open ourselves more radically to the advent of differences, to the dance of joyful knowledge.” (Source pdf)

The exhibition took place at the IMEC archive (l’Institut Mémoires de l’édition contemporaine) in Normandy, France. This is the same archive that holds more than 12,000 of the note cards of writer and philosopher Roland Barthes.

I’d have loved to visit the exhibition, since this is basically cat-nip for me. Here’s part of the introduction:

“Step into Georges Didi-Huberman’s studio! A philosopher and art historian, he meticulously collects fragments of texts, photographs, and images of all kinds. As a craftsman of thought, he assembles them to create visual and textual constellations to capture our reality. Imec invites you to explore this unique “dialogue machine” and enter the heart of a tirelessly repeated writing process: looking at images, collecting fragments of thought, and telling the world through the montage of ideas.” (Source)

Well, we might have missed the exhibition, but we can still watch a presentation on YouTube (perhaps with English subtitles).

And we can watch some of the short videos presented in the exhibition itself.

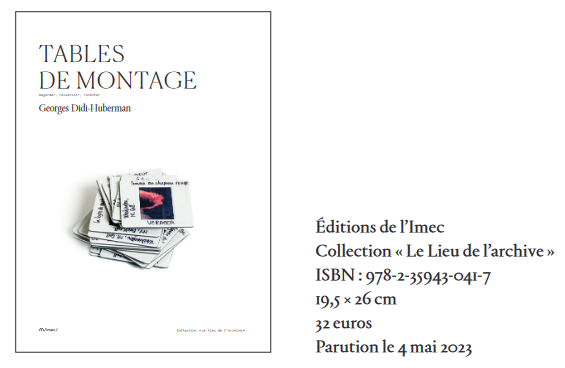

And finally, yes, there is a book of the exhibition.

This vast constellation of 148,000 notes shows that the art of creative note-making is alive and well. And this is not just an archive but a philosophy of thinking and writing. Didi-Huberman’s three-stage creative rhythm: patient collection, exhilarating reassembly, and musical composition, shows how fragments, properly arranged, may reveal unexpected truths. His practice is a reminder that notes exist not necessarily as endpoints, but as invitations to a dance.

For a weekly email digest of all the posts here, you may subscribe.