The Toe of the Year and the Curious Case of John Donne's Missing Commonplace Book

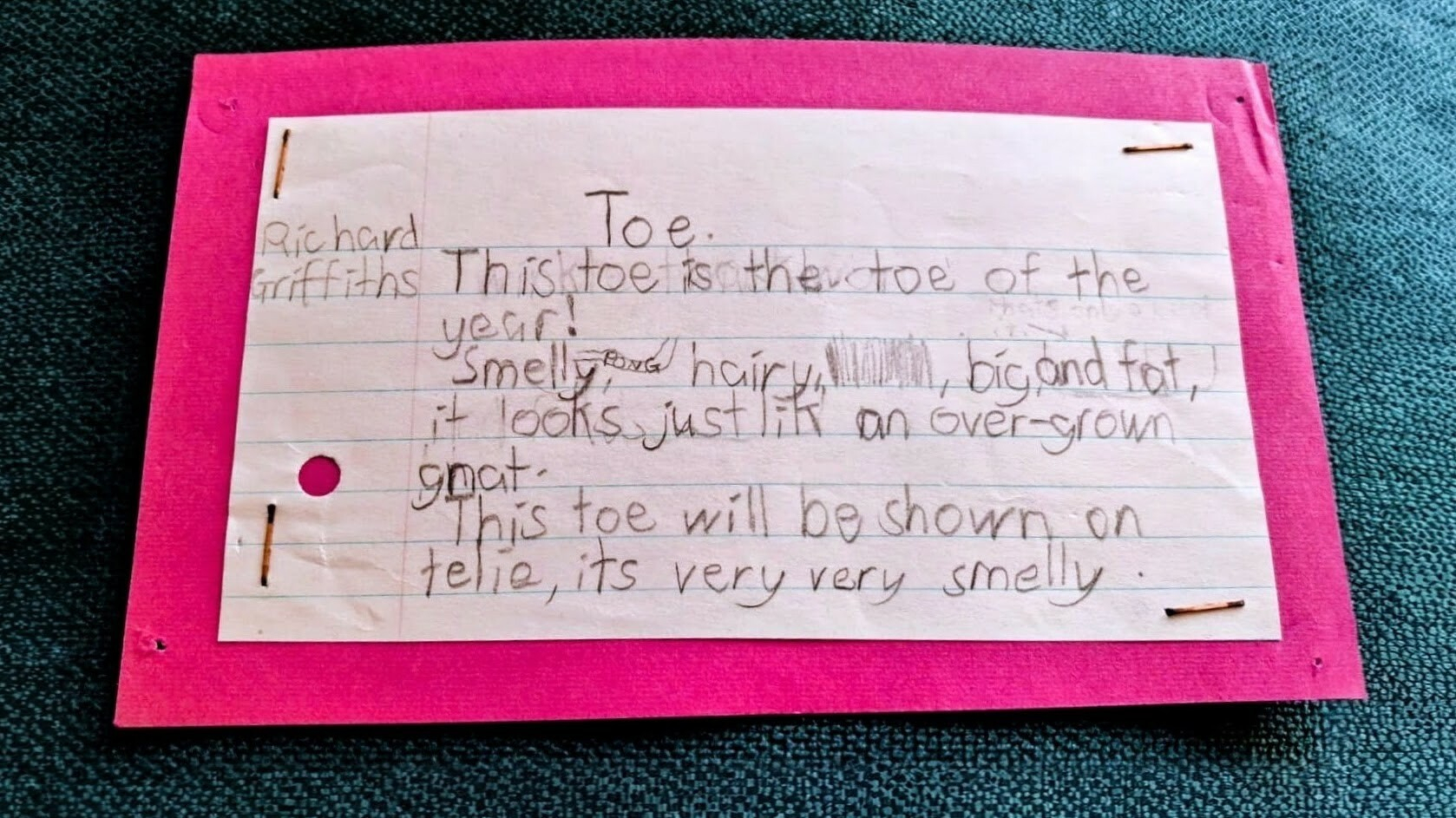

Last month, while my sister was moving house, she discovered a box of papers she’d never seen before. Inside was a collection of documents, decades old, that our parents must have gathered and kept from our childhood. There in a carefully wrapped pile was a sheaf of my sister’s old school reports. And next to them was a set of poems I must have written way back when I was a primary school student.

Perhaps you’ve had the experience of venturing into the attic or the basement and finding long-forgotten documents like these. But this chance rediscovery got me thinking about just how much has been lost to time.

Mostly we don’t bother archiving, and even when we do, there are later moments when we decide to spring-clean, rationalise, declutter, or tidy up.

These are all euphemisms for destroying the evidence.

Not that we shouldn’t do it, but I couldn’t help wondering at the sheer immensity of what must have been lost to history in this way. Admittedly, my childhood poetry and my sister’s school reports aren’t entirely essential for the public record, but what about the other items that well-meaning tidiers have chucked out? Some proportion of them, surely, must have been priceless.

Writing survives through luck and neglect

Given all the destruction of the centuries, and even just the spring-cleaning, it’s amazing that so much of the past still remains available to us, especially through the writing of contemporaries.

To take just one famous example: Leonardo da Vinci’s notes were almost lost because he left them to his favourite student, whose son inherited them and neglected them in a mouldering attic. Despite — or perhaps because of — the neglect, the notes survived and so today we can still marvel at Leonardo’s quickness of thought, virtuosity of line, and genius of innovation.

It’s a big win for forgetting to clear out the attic.

We’re not quite so lucky with John Donne, the poet of the English Renaissance, whose name, for some reason, is pronounced ‘Dunn’. His poems survive, but his commonplace book is currently lost — though its trail is tantalizingly clear.

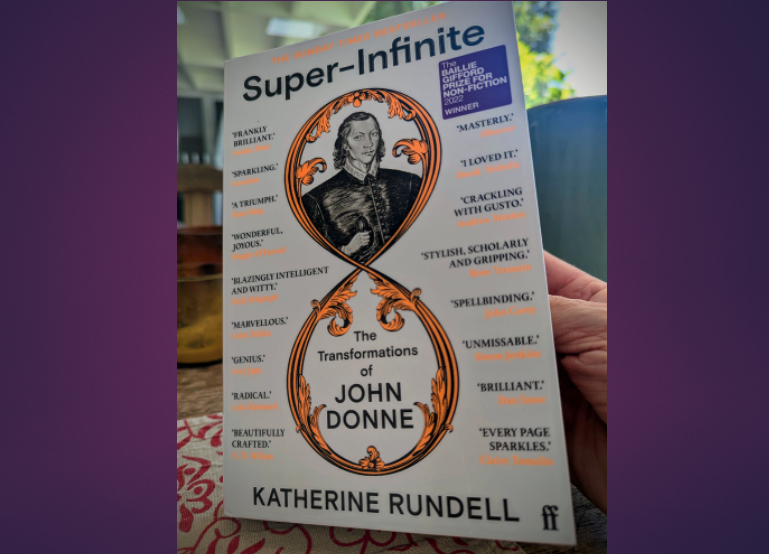

According to Katherine Rundell’s lively biography Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne, Donne gave it to his eldest son, who left it to Izaak Walton’s son in his will. That made sense because Walton was Donne’s friend and biographer. But Walton’s son in turn left all his books and papers to Salisbury Cathedral. And that’s where the trail goes cold.

The commonplace book is completely missing.

Perhaps one day they’ll rediscover Donne’s commonplace book. If it’s ever found, Rundell says, it will cause ‘joyful chaos’ among the Donne community. On reading this I couldn’t decide which I loved more: the delightful concept of joyful chaos, or the endearing fact that there’s such a thing as the Donne community.

Donne’s genius depended on gathering scraps

The loss, for fans of the poet, is particularly frustrating because Donne wouldn’t be Donne without his commonplace book. He lived in what we might call the golden age of commonplacing. It was an era that nurtured his collector’s sensibility and his obsession with hoarding the quotations of others. As Samuel Johnson said disapprovingly, in Donne’s work “the most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together.”

But this magpie tendency, as Rundell calls it, to gather and juxtapose, was hardly a flaw; it was central to his genius. Throughout his poetry, Rundell says, “one thought reaches out to another, across the barriers of tradition and ends up somewhere fresh and strange.”

Though Donne himself coined the term ‘commonplacer’ (another fact I learned from Rundell’s biography), the practice itself was codified by Erasmus, the doyen of Dutch humanism. He instructed readers to create headings at the top of each page, such as beauty, friendship, faith, hope, the vices and virtues. Then, while reading, you’d note down anything striking: a story, a fable, a pithy remark, a clever turn of phrase. The result was both a form of scholarship and a map of your own obsessions. Donne’s book, says Rundell, surely included: angels, women, faith, stars, jealousy, gold, desire, dread, death.

But of course, we don’t know. We haven’t seen it.

The purpose of the commonplace book wasn’t mere collection. As Erasmus explained, whenever a witty occasion demanded, you’d have “ready to hand a supply of material for spoken or written composition.” But despite this, the commonplace book wasn’t really designed for regurgitation. It offered raw material for a combinatorial, plastic process; a process that was half evidence-building and half treasure-hunting.

Like any intellectual pursuit, commonplacing created anxiety about doing it right. Even back then the market naturally monetised that worry, by selling ready-made commonplace books with the quotations already filled in. I find this amusing, but buying pre-compiled wisdom surely defeated the point. It’s the early equivalent of getting a chat bot to do your homework for you: easy but almost pointless.

The work itself is the point.

Sir Robert Southwell, President of the Royal Society, left some headings in his commonplace book forever blank (Academia and Tedium, tellingly), while others left him scribbling in increasingly tiny handwriting at the foot of the page, crossing out headings to make space. Each commonplace book is the unique record of the workings of a unique mind.

Donne built palaces from unrelated bricks

You can see the commonplace book’s influence throughout Donne’s poetry. In a single poem he might reference Aristotelian logic, Ptolemaic astronomy, Augustine’s discussion of beauty, and Pliny’s theory on poisonous snakes. In a poem about sexual inconstancy, he compares women to both foxes (apparently fairly normal for his day) and goats (apparently and understandably unusual).

The Twentieth Century poet T.S. Eliot understood what made this work. “When a poet’s mind is perfectly equipped for its work,” he wrote, “it is constantly amalgamating disparate experience.” For ordinary minds, experience remains chaotic, irregular, fragmentary. But for Donne, as Katherine Rundell observes,

“apparently unrelated scraps from the world were always forming wholes. Commonplacing was a way to assess material for those new connections: bricks made ready for the unruly palaces he would build.”

Donne himself was alert to the danger of mindless compilation. In his poem “Satire 2,” he mocked writers who merely copied others' words and regurgitated them as their own: like someone who eats your food and then claims the resulting waste as their supposedly better creation. Harsh, but memorable. And yes, the analogy certainly did make me think of ChatGPT and its copyright-denying siblings.

But he is worst, who (beggarly) doth chaw

Others' wits' fruits, and in his ravenous maw

Rankly digested, doth those things out spew,

As his own things; and they are his own, ‘tis true,

For if one eat my meat, though it be known

The meat was mine, th’ excrement is his own.

What lessons emerge from a book we’ve never seen?

First, you can’t simply jam together random quotations and expect to produce thoughtful prose. Johnson accused Donne of yoking heterogeneous ideas together by violence, yet Eliot saw that Donne’s “perfectly equipped poet’s mind” achieved something remarkable. The rest of us may need to work harder to overcome the illusion of integrated thought and produce the real thing.

Second, commonplacing risks collecting other people’s words without fully digesting them. Apparently there’s a German word for the kind of writing this can produce: Zitatsalat, ‘citation salad’. There are other methods — the Zettelkasten system, for instance, which I prefer — that encourage reflection and connection-making from the outset. I’ve taken a minimal approach to making notes, with just these affordances.

Third, it’s important to publish, not least because unpublished notes often end up lost. Leonardo da Vinci’s notes barely survived. Donne’s commonplace book is long gone (though I encourage you to check down the back of your sofa just in case). A scholar of the philosopher Charles Peirce recently told me that after Peirce left his voluminous papers to a university library, they reused them as scrap paper. Happily, someone realized the error before too much damage was done. And to cap it all, my own poem about the toe of the year nearly didn’t make it. And these days, when you’re gone someone will eventually press “delete.” Better to get your words out there while you can.

A short postscript:

Indeed, this very article was almost the victim of delayed publication. I wrote this, mostly, three months ago. Then my iPad’s note-writing app developed a mysterious glitch which made the app and all its notes unusable. Only the happy fact that I’d backed everything up ensured my words would be saved from the digital wreckage. Otherwise, oh the horror, as with Donne’s Commonplace book, you wouldn’t be reading this right now.

—

Further reading:

Rundell, Katherine. Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne. New York City: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022. ( see especially pages 36-39, the source of most of the quotes here )

Overcome the illusion of integrated thought

A minimal approach to writing notes

Get your words out there by publishing first

—

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now.

And if you found this article interesting you might like to sign up to the Writing Slowly weekly email digest. You’ll receive all the week’s posts in that handy email format you know and love.