Lord Acton took too many notes, but that doesn't mean you have to

It’s intriguing to discover a prolific author with a working collection of 148,000 notes, but it begs the question: can you make too many notes?

I mean, surely there comes a point where your note-making gets in the way of the outcomes you’re looking for, and the endless writing of notes starts to defeat its very purpose.

Well, maybe. Here’s a little cautionary tale from the Nineteenth Century, a time when both empire and facial hair were unrestrained by decency.

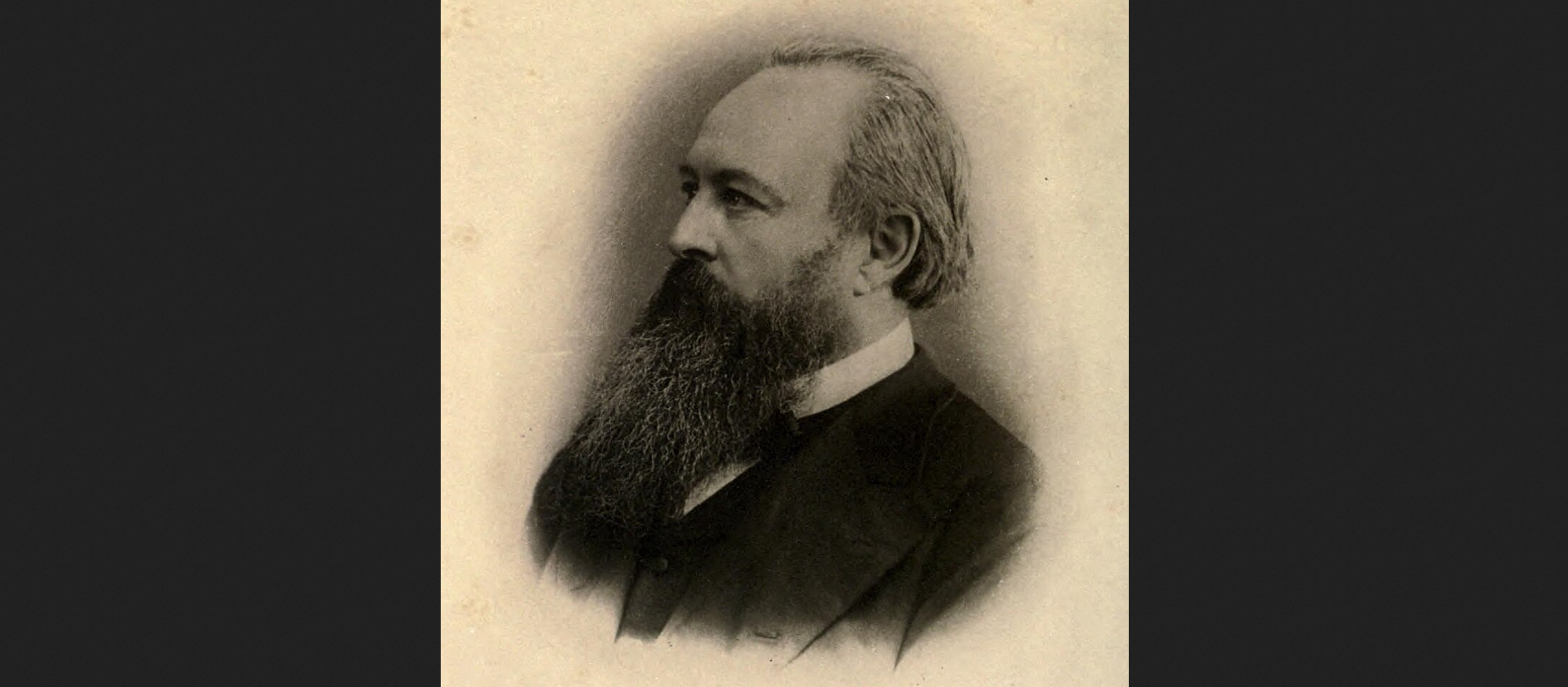

John Dalberg-Acton (1834-1902) was a significant British political figure of the Victorian era. Did he have one of those massive walrus mustaches that they all seemed to go in for back then? Well sort of, but he also had the type of beard that make it look like its owner has just swallowed a beaver, so frankly it’s hard to tell.

He was also an important historian who nevertheless published very little in his lifetime. The consensus seems to be that he took too many notes.

Acton’s Encyclopedia Britannica (11th Edn) entry reads in part:

“Lord Acton has left too little completed original work to rank among the great historians; his very learning seems to have stood in his way; he knew too much and his literary conscience was too acute for him to write easily, and his copiousness of information overloads his literary style. But he was one of the most deeply learned men of his time, and he will certainly be remembered for his influence on others.”

By the way, it’s topical to talk about Lord Acton. He has indeed been remembered, but chiefly for his prescient aphorisms:

“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

“There is no worse heresy than that the office sanctifies the holder of it.”

No prizes for guessing which Scofflaw-in-Chief this is a reminder of. Too many notes? Sad! But I digress.

That’s not all. Here’s Keith Thomas in an entertaining London Review of Books piece.

“It is possible to take too many notes; the task of sorting, filing and assimilating them can take for ever, so that nothing gets written. The awful warning is Lord Acton, whose enormous learning never resulted in the great work the world expected of him. An unforgettable description of Acton’s Shropshire study after his death in 1902 was given by Sir Charles Oman. There were shelves and shelves of books, many of them with penciled notes in the margin. ‘There were pigeonholed desks and cabinets with literally thousands of compartments into each of which were sorted little white slips with references to some particular topic, so drawn up (so far as I could see) that no one but the compiler could easily make out the drift.’ And there were piles of unopened parcels of books, which kept arriving, even after his death. ‘For years apparently he had been endeavouring to keep up with everything that had been written, and to work their results into his vast thesis.’ ‘I never saw a sight,’ Oman writes, ‘that more impressed on me the vanity of human life and learning.’’

According to Oman, in his book, On the Writing of History (1939), Lord Acton left behind only one good book, some lectures, and several essays scattered in hard-to-find journals. He also created a plan for a large history project that others would write after his death, but not in the way he had intended.

In 1998 the historian Timothy Messer-Kruse drew entirely the wrong conclusion from all this. He seemed to point the blame for Lord Acton’s little problem on the fact that all he had to work with was compartments full of paper notes:

“What may have been accomplished had Acton possessed more than a row of dusty pigeon-holes to store his notes and musings?”

Would perhaps a computer have helped him out, by any chance? Yes indeed:

“The advances in computing and communication technologies over the past thirty years have laid the material basis for overcoming the Lord Acton syndrome that continues to plague the historical profession. It is now possible for the Lord Actons of today to share an unlimited number of their notes, ideas, and annotations with the entire world of interested scholars with minimal cost. Paperless publishing through the Internet theoretically offers the means for transcending a centuries-old model of historical scholarship and breaking down the barriers between academic and amateur historians.”

Well, we’ve had another 27 years of the digital era since then, and it’s probably safe to say that while there’s certainly a ‘Lord Acton Syndrome’, the cure is not more computers.

If anything, the situation is even worse now, made so by the massive expansion of available information. Imagine what Acton would have done with all the many terabytes of historical data that’s now available at the click of a button.

That’s right: he’d have made notes on it.

In fact, Charles Oman had already understood the poor man’s real problem much earlier.

Oman saw that this limited output from such a capable scholar happened because Lord Acton tried to master everything before finishing anything. Apparently he had a great book in mind, but gathering all the necessary information became overwhelming for one person.

The lesson, for Oman at least, is clear:

“In short the ideal complete and perfect book that is never written may be the enemy of the good book that might have been written. Ars longa, vita brevis— one must remember the fleeting years, or one’s magnum opus may never take shape, if one is too meticulous in polishing it up to supreme excellence.”

Being too focused on perfection might mean our greatest work (or indeed any work) never materializes at all.

So take look in the mirror. Are you a walrus? Have you swallowed a beaver? No? Then you don’t need to copy Lord Acton’s note-taking excesses either. Make some notes, sure, but please don’t ‘do an Acton’ and die before you make something from them.

Footnote:

Oman complained about the seemingly hopeless diversity of Lord Acton’s interests, as evidenced from the wide range of his notes - from pets, to stepmothers to totems. Well, I’m not convinced this is a problem in itself. In the right hands it might even be an advantage. The real problem was that Acton doesn’t seem to have developed a system for writing, beyond the publication of his lectures.

“There were pigeon-holed desks and cabinets with literally thousands of compartments, into each of which were sorted little white slips with references to some particular topic, so drawn up (so far as I could see) that no one but the compiler could easily make out the drift of the section. I turned over one or two from curiosity—one was on early instances of a sympathetic feeling for animals, from Ulysses' old dog in Homer downward. Another seemed to be devoted to a collection of hard words about stepmothers in all national literatures, a third seemed to be about tribal totems.” See also: The mastery of knowledge is an illusion

Acknowledgement

Ched Spellman posted about Lord Acton’s problem 15 years ago. Now I’m just commenting on Spellman’s commentary on Thomas’s commentary on Oman’s commentary. Yes, this is the Internet. What did you expect?

References

Hugh Chisolm (1910) ‘Acton, John Emerich Edward Dalberg’, in Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Edition. Vol 1, pp. 159ff. Internet Archive.

Timothy Messer-Kruse (1998) ‘Scholarly publication in the electronic age’, in Dennis A. Trinkle. Writing, Teaching and Researching History in the Electronic Age: Historians and Computers. London: Routledge. p. 41.

Charles Oman (1939), On the Writing of History. 1st Edition, London: Routledge. doi.org/10.4324/9…

Keith Thomas (2010), ‘Diary: Working Methods’. London Review of Books. Vol. 32 No. 11 · 10 June 2010. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v32/n11/keith-thomas/diary

Congratulations! Since you’ve made it right to the bottom of this page, you might also like to subscribe to the weekly email digest.