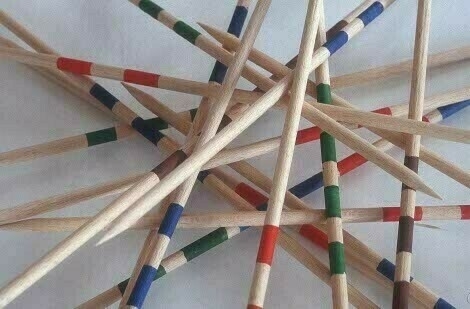

📷 photo challenge day 4: nostalgia. Can you tell what these are? #mbjune

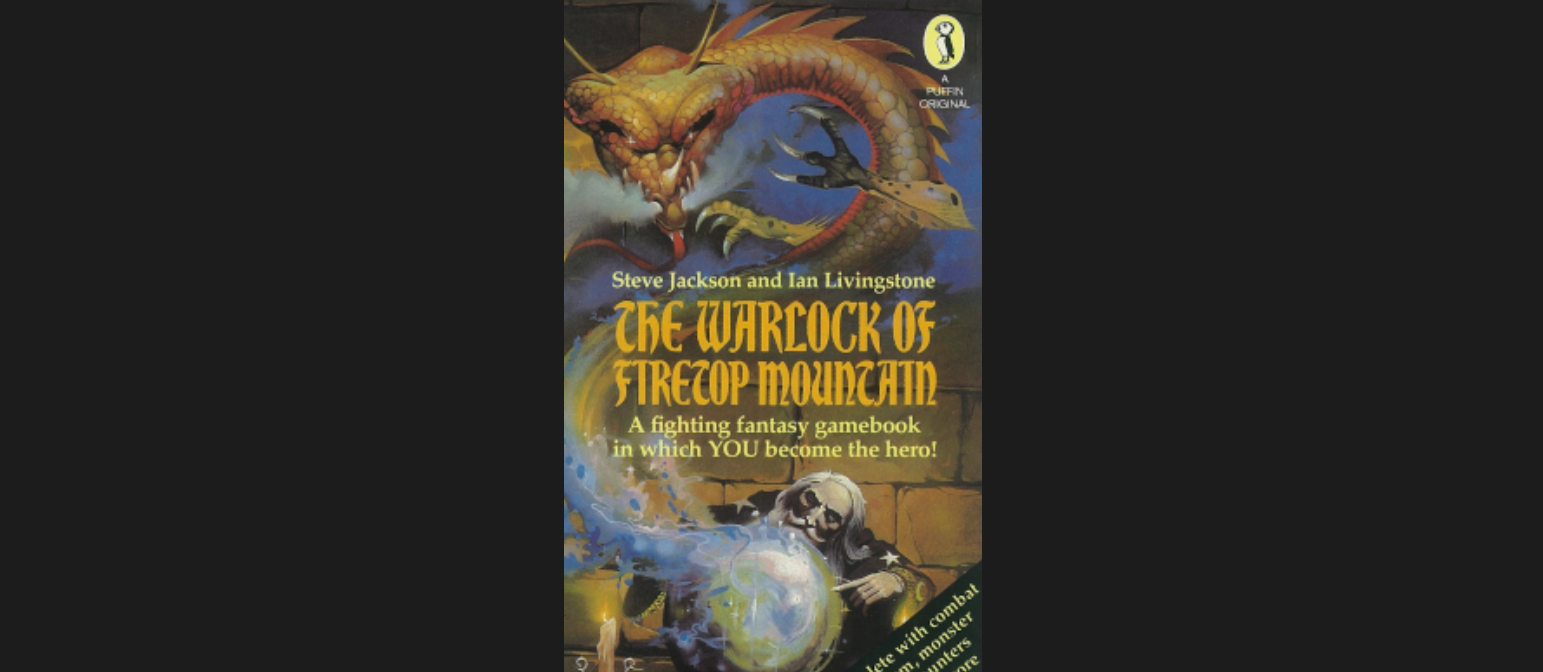

💬 “There’s a left-field way of thinking about the world that doesn’t follow the straight path. The route forward doesn’t have to lead in one true direction but potentially many.”

Non-linear narratives inspire non-linear notes.

📷 Day 3: shadow #mbjune.

💬 “My work grows from the duel between the isolated individual and the shared awareness of the group.” - Louise Bourgeois, 1954.

See the whole photogrid.

Finished reading: This Is Happiness by Niall Williams 📚

A shaggy dog story in the best possible sense. I re-read several passages to try to work out how the author achieved his almost magical prose. Friends who read it said they felt not much happened. I felt not much happened, miraculously.

What I've learned from non-linear narratives

Thoughts on how non-linear narratives have profoundly influenced my reading and writing practices, allowing for a more organic and interconnected approach to storytelling and knowledge creation.

When did you first hear about making notes the Zettelkasten way?

#pkm #zettelkasten #notetaking

Daniel Wisser’s notecards as art and archive

Daniel Wisser’s exhibition in Vienna features 60 index cards with sketches of stories displayed in a note box (Zettelkasten).

What Tim Berners-Lee Has to Teach About Effective Notes

Tim Berners-Lee’s insights on the interconnected nature of knowledge have inspired a flexible, web-like approach to note-making that mirrors my natural thinking rather than some restrictive categorization.

How I learned to make useful notes the Zettelkasten way

I encountered Niklas Luhmann’s sociological work in 1990 but only came across his Zettelkasten approach in 2007, thanks to historian Manfred Kuehn’s wonderful but sadly defunct blog Taking Note Now.

I gradually converted my existing personal wiki from then on, at first emulating Kuehn’s use of Connected Text an also sadly defunct app. So that’s 17 years and counting.

It has taken ages to get to a system that works well for me, but I think I’ve got there now. 🤞

“The rapid passage of time is a complete antimeaning machine. Doesn’t life absolutely require tactical slowing down if a person, even a smart, serious, concerned one, is to find the time and space to make meaning?” - Eric Maisel

Tactical slowing down is great, but then writing slowly is a whole strategy.

“No writing is wasted. Did you know that sourdough from San Francisco is leavened partly by a bacteria called lactobacillus sanfrancisensis? It is native to the soil there, and does not do well elsewhere. But any kitchen can become an ecosystem. If you bake a lot, your kitchen will become a happy home to wild yeasts, and all your bread will taste better. Even a failed loaf is not wasted. Likewise, cheese makers wash the dairy floor with whey. Tomato gardeners compost with rotten tomatoes. No writing is wasted: the words you can’t put in your book can be used to wash the floor, to live in the soil, to lurk around in the air. They will make the next words better. "

Erin Bow, Anti-advice for writers

Leibniz created a haystack of notes that wouldn't fit in his Zettelschrank

Gottfried Leibniz, a prolific yet disorganized thinker, struggled to manage an overwhelming influx of ideas, resulting in a vast but minimally published literary legacy. Is this a cautionary tale or some other kind of tale? I have an opinion.

Sinister Zettelkasten?

The 2025 Sydney Film Festival program features Jodie Foster’s new film, “Vie privée,” accompanied by a marketing image that evokes mystery with index card boxes in the background.

“You only come to know these things in hindsight – when you look back and see the precarious chain of events, happenstance, and good fortune that led to wherever you are now. Before you reach that point, you have no way of predicting which idea will make a difference and which will die on the vine. That’s why you record them all. No matter how random, how small, how half-baked, how unfinished it may be; if you have a thought, record it right away.” ― Antony Johnston, The Organised Writer.

From a single idea to many, and from networks of linked ideas to reconfigured networks of knowledge. I found a way to create order from my jumbled ideas.

#zettelkasten #writing #learning #pkm #notetaking #writingprocess #learningstrategies

I found a way to create order from my jumbled ideas

A discussion of the SOLO taxonomy model of learning, which emphasizes the progression from disorganized ideas to structured knowledge through atomic notes and meaningful connections.