📷 Photo challenge day 18: texture.

Furry or spiky? Spotted on a boardwalk in the Royal National Park near #Sydney - as featured in day 2.

#mbjune

What I Learned from Bob Doto about Making Effective Notes and Writing a Book

Historian Dan Allosso led a discussion on Bob Doto’s insights on flexible note-taking and writing processes. It emphasised the importance of iterative development and audience engagement. Here are my notes.

📷 Photo challenge day 17: warmth.

We saw a curious warning at this year’s Vivid, the big winter festival of light in #Sydney. #mbjune

📷 Photo challenge day 16: blur. A smoking ceremony at Prince Alfred Park, #Sydney. #mbjune

Influence is everything: novelty its flimsy dress

This whole article dumbed down by AI summary: Cultural trends often leave behind valuable ideas that merit revisiting rather than being dismissed as unfashionable. And I thought I was being clever.

Finished reading: Spring, Summer, Asteroid, Bird: The Art of Eastern Storytelling by Henry Lien 📚

A ‘how-to’ book on kishotenketsu, a Japanese storytelling concept that’s an alternative to ‘the hero’s quest’. Like many such books, it’s worth reading just for the summaries of example stories.

💬"When you’re writing, you’re trying to find out something which you don’t know. The whole language of writing for me is finding out what you don’t want to know, what you don’t want to find out. But something forces you to anyway." - James Baldwin. Paris Review, The Art of Fiction No. 78. no. 91, 1984.

📷 Photo challenge day 15: tie. This is how the tugboat from day 9 was secured to the wharf at Pyrmont, #Sydney. #mbjune

Photo challenge, day 14: twilight at the mouth of Deerubbin, the Hawkesbury River #mbjune #Sydney

📷 Photo challenge day 13: pathway. Calna Creek, just north of #Sydney. #mbjune

📷 Photo challenge day 12: hidden.

It’s easy to watch the annual ‘humpback highway’ whale migration at Malabar Headland in #Sydney - so you might easily miss this guy, who is looking the other way.

#mbjune

Worth repeating and re-repeating:

“the evidence shows that regularising migration is a positive-sum game, in economic, social and security terms.”

A definitive study of a hotly debated phenomenon: migration into Europe and America, its socioeconomic impacts, and the eternal policy efforts to stop the inevitable.

#migration

📷 Photo challenge day 11: brick.

#Sydney has more than one Japanese garden, but only one is owned by geese.

#mbjune

📷 Photo challenge, day 10: rail.

Of the many wonderful exhibits at the NSW Rail Museum, this little railbus is one of my favourites. Though small, it still gets a Wikipedia entry.

#mbjune #Sydney #railwayheritage

📷 Day 9: wood. There’s a truly massive amount of timber in the old wharves around Sydney Harbour. #mbjune #Sydney.

See the whole photogrid.

A search for meaning in the palace of lost memories: Thoughts on Piranesi, a novel by Susanna Clarke

Susanna Clarke’s novel Piranesi has got me thinking about memory, identity, the fallibility of writing, and the paradox that intrinsic value might be created rather than found

📷 Photo challenge day 8: travel. Most of the photos this month are of #Sydney, but given today’s theme, this was taken as far from Sydney as it’s possible to get. #mbjune

Who says you have to choose between yourself and others? The case for intelligent generosity

It’s not rocket science but if you want to foster sustainable generosity and human flourishing here’s how to cultivate a balance between caring for yourself and supporting others.

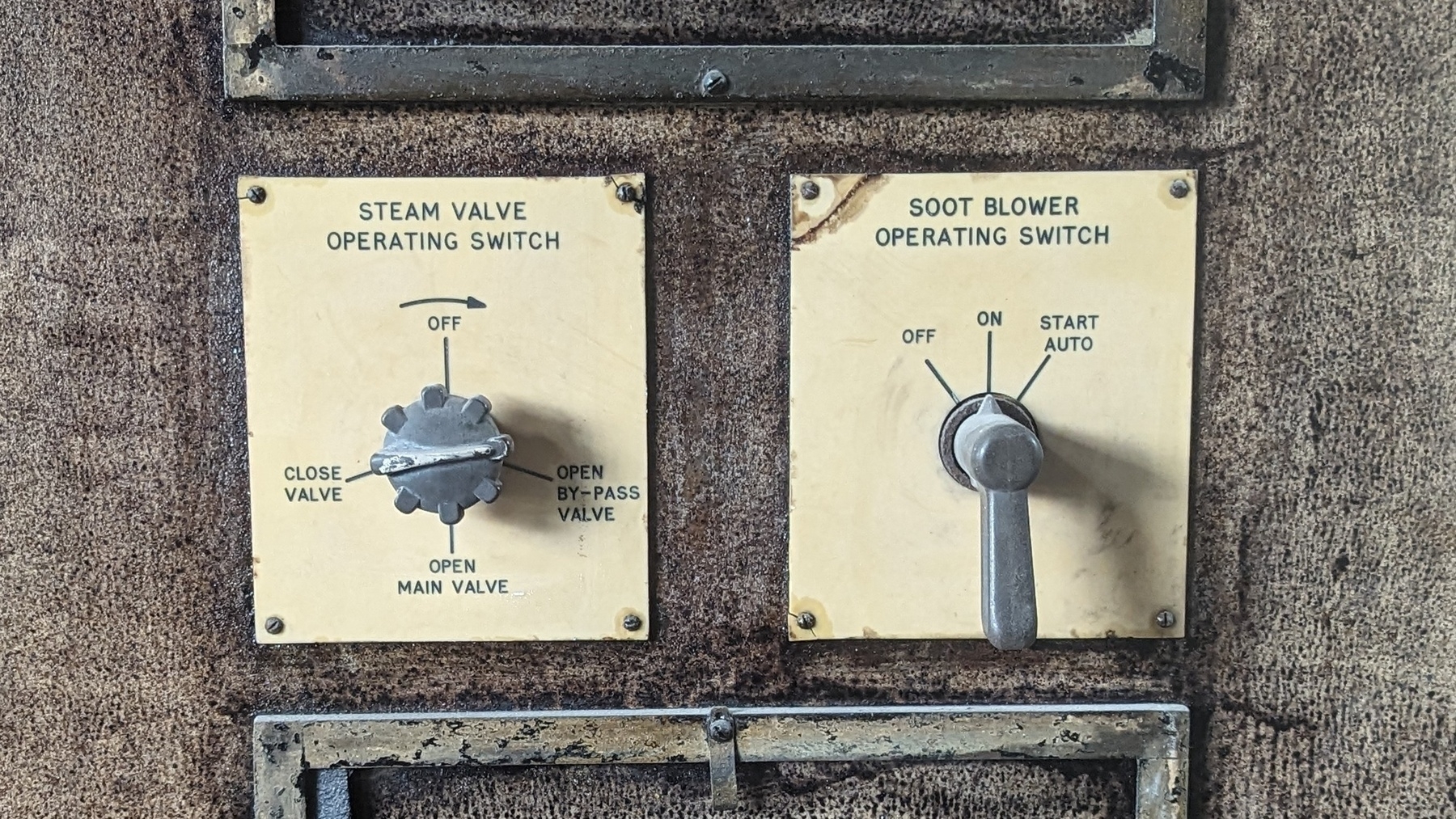

📷 micro.blog photo challenge day 7: switch. #mbjune

This is what nuclear ‘decommissioning’ looks like: a debacle. #nuclearindustry

“The NDA expects the clean-up of the Sellafield site to go on until 2125 and cost £136 billion ($184 billion), an estimate which has increased nearly 19 percent since March 2019.”

www.theregister.com/2025/06/0…

HT: Glyn Moody, Mastodon