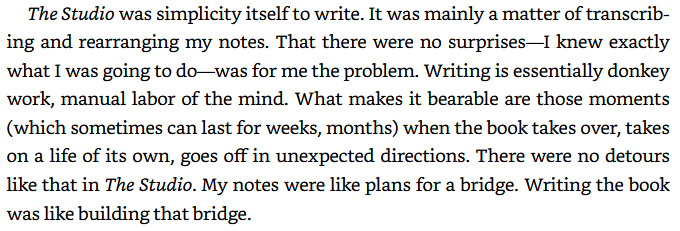

Maybe you can create coherent writing from a pile of notes after all

“My notes were like plans for a bridge”.

I’ve argued that you can’t create good writing just by mashing your notes together and hoping for the best. That’s the illusion of connected thought, I’ve said, because you can’t create coherent writing just from a pile of notes.

Well, maybe I was wrong.

Perhaps a strong or experienced writer can do exactly that. Here’s John Gregory Dunne, the journalist husband of Joan Didion, in the Foreword to his 1968 book on Hollywood, The Studio:

I imagine he wasn’t just a good writer, though.

Surely he was first a very good note-maker.

I’d like to hear about people’s experiences, good and bad, of using their notes to create longer pieces of writing. Was it like building a bridge, or perhaps like building a bridge out of jelly?

HT: Alan Jacobs, who draws a different but very valid lesson from the anecdote.

Stay in the Writing Slowly loop and never miss a thing (unless you don’t get round to opening your emails, in which case, yeah, you might miss a thing. Anyway:

Read better, read closer

For anyone seeking clues on better techniques for reading, Scott Newstok, author of How to Think Like Shakespeare, has created a marvelous resource: a close reading archive. Here is where all your close reading questions will be answered, including, what is it? how do you do it? what have people done with it? and does it have a future in a digital age?

Close reading is one of those two-word phrases that seem to take on a life of their own. Anyone connected to the humanities has probably heard of it, but it’s not necessarily well understood. Is it finished? Apparently not. Not at all.

Professor Newstok’s close reading archive is an openly available companion to John Guillory’s cultural history, On Close Reading, published January 2025.

Newstok is also editor of a book on Montaigne’s view of teaching, which is how I discovered Gustave Flaubert’s endorsement of what might perhaps be seen as a kind of close reading avant la lettre1:

“Read Montaigne, read him slowly, carefully! He will calm you . . . Read him from one end to the other, and, when you have finished, try again . . . But do not read, as children read, for fun, or as the ambitious read, to instruct you. No. Read to live.”

Now consider: three ways to make notes while reading.

For even more, please subscribe.

-

but don’t take my word for it, what do I know? Read the book and the close reading archive. ↩︎

Improve your notes (and your life) with two-word phrases

I’ve been discovering the power of two-word phrases in innovation and branding. This article illustrates their impact through historical examples and modern applications.

Year in books for 2024

Happy New Year!

Here are some of the books I finished reading in 2024.

Happy New Year!

Do you have annual reading goals? And do you kep a record of your reading? I posted a little gallery of the books I finished reading in 2024. Micro.blog, the web service I use, is great for this. But it only works if I actually use it! Which is why only some of my reading was captured.

So my reading resolution for 2025 is to be more systematic in recording my reading.

In the past few years I’ve set a target. This has helped me to understand my reading cadence, but now I know it, I don’t really need a target any more. It’s not like there’s a big reward to be had for reading 1000 books a year!

How about you? How do you keep track? What works? And do you have any specific book goals for 2025?

Here’s a fascinating podcast episode about Andrew Hui’s new book. The Study.

“With the advent of print in the fifteenth century, Europe’s cultural elite assembled personal libraries as refuges from persecutions and pandemics. Andrew Hui tells the remarkable story of the Renaissance studiolo–a “little studio”–and reveals how these spaces dedicated to self-cultivation became both a remedy and a poison for the soul.”

I’ve written previously about the ideal creative environment, but the history of the studiolo is new to me.

Zettelkasten anti-patterns

When developing your Zettelkasten, your collection of linked notes, what have you learned not to do?

Mathematician Alex Nelson keeps a paper Zettelkasten, and has posted online about how he does it. He calls this Zettelkasten best practices.

But Nelson also lists some ‘worst practices’ to avoid, which he calls anti-patterns.

So I’m wondering, do you have any other examples of ‘Zettelkasten anti-patterns’ from your own experience?

For reference, here are the ‘anti-patterns’ Nelson identifies. I’m not going to explain these here, though, because you can read the post for yourself:

-

Using the Zettelkasten (or Bibliography Apparatus) as a Database

-

Collecting Reading Notes without writing Permanent Notes

-

Treating Blank Reading Notes as “To Read” list

-

Forgetting to write notes while reading

Are there any more Zettelkasten worst practices, and how have you avoided them?

💬 “Put something on the Web, and do it for free”.

Here’s one for the #Zettelkasten and #PKM tragics: a dive into the pre-history of ‘atomic notes’.

writingslowly.com/2024/11/2…

Atomic notes and the unit record principle

Thinking about atomic notes

Researcher Andy Matuschak talks about atomicity in notes, an idea also developed by the creators of the Archive note app, at zettelkasten.de.

To make a note ‘atomic’ is to emphasise a single idea rather than several. An atomic note is simplex rather than multiplex. And this form of simplicity relates to the idea of ‘separation of concerns’ in computer programming.

Back to the unit record principle

But the idea is much older than this. I found something very similar described in 1909, in The Story of Library Bureau.

How to write a better note without melting your brain

There’s a great line in Bob Doto’s book [A System for Writing][2] which goes like this:

“The note you just took has yet to realize its potential.”

Haven’t you ever looked at your notes and had the same thought? So much potential… yet so little actual 🫠.

Perhaps you jotted something down a couple of days or weeks ago and returning to it now you can’t remember what you meant to say, or what you were thinking of at the time.

Or perhaps you made a great note then, but now you can’t find it.

Or maybe you just know your note connects to another great thought… but you can’t for the life of you remember what.

Well I already make plenty of half-baked notes like these, but how can I make them better? It’s not something they teach in school, so most of us don’t even realize there’s untapped potential, if only we could access it.

So, how can I make worthwhile notes from my almost illegible scribbles on the fly? Well, here’s what works for me. Maybe it’ll work for you too.

When writing my notes, I just have a few simple rules that I mostly stick to:

In The Atlantic Arthur Brooks suggests three ways to become a deeper thinker. He also ‘solves’ a famous koan.

Meanwhile, my suggestion for deeper thought is simple: make notes.

I still can’t solve koans though.

#PKM #zettelkasten

TIL there’s a tracker for bogong moths! What? Yes, the iconic, endangered species that keeps the critically endangered Mountain Pygmy-possums fed. Thanks for asking. #australianwildlife

The future: They touted a slow race between 1984 and Brave New World. Instead it’s a sprint to the finish for The Handmaid’s Tale and Parable of the Sower. My money’s on Octavia. Came for the hope, stayed for the resistance.

Want to read: On Mysticism by Simon Critchley 📚 Having written about Julian of Norwich as a sci-fi author, I’m very interested in philosopher Simon Critchley’s angle. #philosophy #religion

🗨️ Keanu Heydari on the value of the #Zettelkasten.

“Maintaining a zettelkasten is, in itself, an exercise in Stoic care of the self (epimeleia heautou). This practice is not merely about external organization but about cultivating inner freedom through discipline, mindfulness, and deliberate engagement with knowledge.”

📷 Just returned from hiking in New Zealand, where the sky was blue and the politics torrid. I learned of the Dawn Raids. We can all learn from this shameful history of bungled deportation.

Do I prefer Mastodon or Bluesky? No need to choose, just cross-post from my blog using micro.blog. POSSE FTW.

”You can automatically cross-post your microblog posts to Medium, Mastodon, LinkedIn, Tumblr, Flickr, Bluesky, Nostr, Pixelfed, and Threads.”

Lots of interest in Bluesky lately. I signed up a year ago. Although I hate venture-funded projects, I loved what Paul Frazee did with beaker Browser and want to check out the next iteration. Micro.blog does automatic posting to Bluesky, so it’s POSSE all the way.

Not just notes: another meaning of 'Zettel'

In German, Zettelkasten, quite simply, means ‘note box’. But there’s another, more hidden meaning of the word Zettel (note) that even German-speakers may know nothing of.

All the same, it’s useful for thinking with.

This year, for Halloween, I’m wearing normal clothes. Somebody asked me, “What are you supposed to be?” I said, “I’m a former gifted child. I was supposed to be a lot of things.”

The horror!