The Lost Medieval Library Found in a Romanian Church medievalists.net

Old news, but new to me. I’d love to find a lost medieval library in a tower somewhere, but I might be on the wrong continent for that kind of discovery.

HT: @glynmoody@mastodon.social

Image: Ropemaker’s Tower, Mediaș, Romania (Source. CCby SA4.0)

My notes were full but my heart was empty. Doug Toft travels beyond progressive summarization

Doug Toft discusses his struggle with summarizing reading notes and suggests that writing about what you read, as opposed to simply taking notes, can enhance understanding and retention.

Well the book arrived this morning. Now I really am publishing slowly!

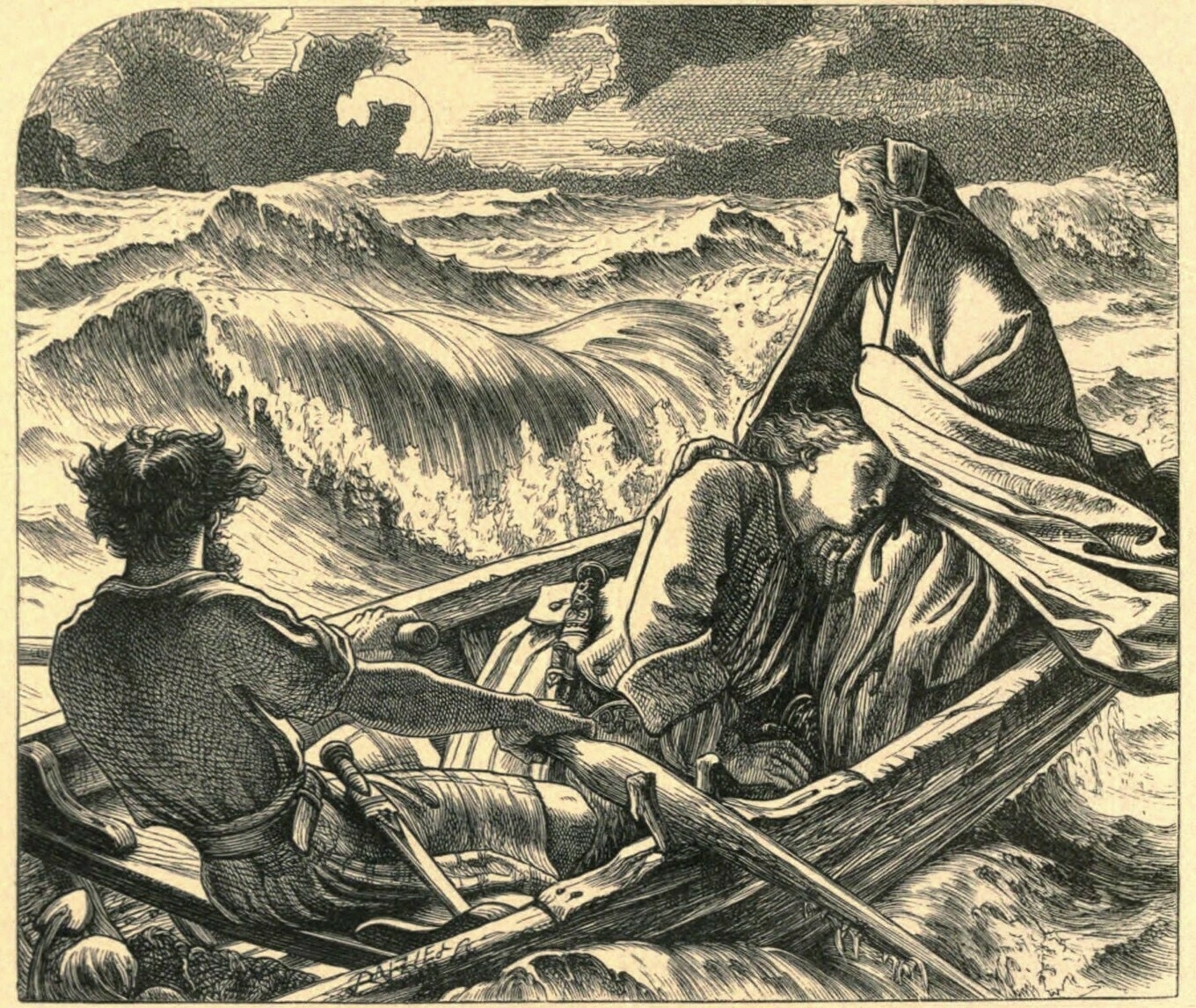

Finished reading: Nothing Left to Fear from Hell by Alan Warner. 📚

This was so piteously moving. The lost cause, the delusional hopes, the petty snobbery, the misplaced loyalties, the few quiet voices of reason, and oh, that startling, poignant ending. The Young Pretender like you never knew.

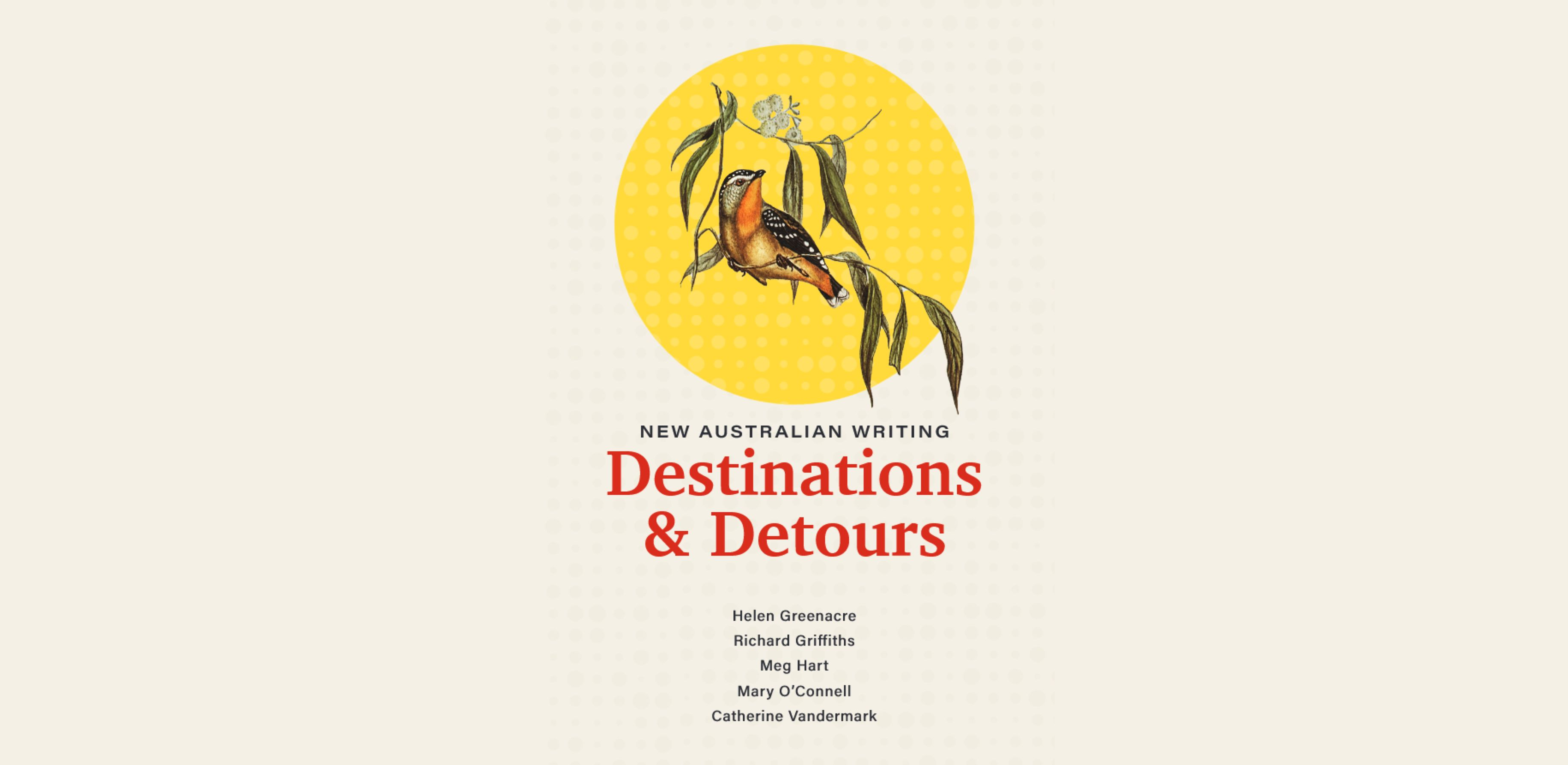

Publishing slowly

I’m writing so slowly that you might be wondering if I’m ever going to get anything published.

Well wonder no more. I’m happy to say extracts of my memoir, ‘The Green Island Notebook’ are published in the anthology Destinations & Detours: New Australian Writing.

Published by Detour Editions, the collection launches here in Sydney on Sunday 2nd March 2025, and if you happen to be in the vicinity, I’d be delighted to meet you in person.

Book Launch 2pm, Sunday 2nd March, at Randwick Literary Institute, 60 Clovelly Road, Randwick NSW

Watch out too for news of how you can get your hands on a copy, wherever in the world you find yourself.

And this isn’t the only news on the publishing front. I’ll be sharing details of some further publishing adventures very soon.

But don’t worry, whatever happens, I’ll still be writing slowly.

Update: Oh look, I wrote another book: Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters.

Randwick Literary Institute, the venue for our book launch, celebrates its 100th anniversary in 2025. Here it is in 1957, and it hasn’t changed much since then:

Subscribe to the Writing Slowly weekly digest (unsubscribe any time):

To care is to disobey

The book Pirate Care discusses how the act of caring for others has been criminalized, and it advocates for a grassroots political practice of solidarity against oppressive legal measures.

I’ve found Natalie Goldberg’s writing prompts to be especially helpful. Maybe it’s the pleasure of a deck of cards I can shuffle and deal.

A great strength of youth is to be able to say, with naive but powerful conviction: “How hard could it be?”

I wrote comics as a child and as a teenager I wrote poetry and plays. It wasn’t hard, I just did it.

What did you achieve then that you doubt now?

It’s worth leaning into that.

💬 “We live in a warehouse of casts that have lost their moulds,” - Roberto Calasso, The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony (1988).

Making meaning where there is none

A quote by Italian author Roberto Calasso parallels the enigmatic environment of Piranesi’s world, in a novel where meaning is derived from seemingly disconnected elements.

A photo of a toy train set from @manton brought back a fond memory: The first time I ever used eBay I was clueless and accidentally won three auctions. The result was enough wooden tracks to cross the whole continent.

My kids were delighted. Now In their mid-twenties, they still have some of that haul.

Old trains.

Currently reading: Wanderlust by Rebecca Solnit 📚

I like walking because it is slow, and I suspect that the mind, like the feet, works at about three miles an hour. If this is so, then modern life is moving faster than the speed of thought, or thoughtfulness.

-Rebecca Solnit; Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Useful Australian software? You’re probably thinking of Canva or Atlassian. And who even knows WiFi is Australian? But my favourite Aussie tool by far is Sublime Text, also made… here in Sydney.

I use it to write my #zettelkasten notes.

James Doyle is a fan too: ohdoylerules.com, and there’s a great discussion on Hacker News.

Torches against pitchforks

There’s a great Dave Coverly cartoon of a worried king looking down from the battlements of his castle at an angry crowd massed just below. His relaxed advisor says, “Oh, you don’t need to fight them - you just need to convince the pitchfork people that the torch people want to take away their pitchforks.”

While the people who always use the correct words in just the right tone use up their wrath on the people who sometimes, in their estimation, don’t quite manage to, the real evil stays focused on growing stronger each day.

PS. a lot of conflict online could be addressed with a simple phone call. Yes, we still have that.

PPS. Did I say torches against pitchforks? Maybe I meant OMG.lol against micro.blog

“Libraries will get you through times of no money better than money will get you through times of no libraries.” - Anne Herbert, The Next Whole Earth Catalog (1980), p 331.

Indeed, what’s more punk than the public library? Flaming Hydra

Create a note system that indexes itself

Niklas Luhmann’s Zettelkasten system exemplifies a self-indexing record-keeping method. It allows efficient organization of notes through associative linking rather than through traditional indexing.

Semantic line breaks are a feature of Markdown, not a bug

The adoption of semantic line breaks in Markdown enhances clarity by encouraging writers to isolate each sentence while allowing for visually appealing paragraph formatting. It’s a superpower I didn’t know I had - until now.

💬 “It was mainly a matter of transcribing and rearranging my notes… My notes were like plans for a bridge. Writing the book was like building that bridge.” - John Gregory Dunne, The Studio, 1968.

Maybe you can create coherent writing from a pile of notes after all. writingslowly.com

💬“Read Montaigne, read him slowly, carefully! He will calm you . . . Read him from one end to the other, and, when you have finished, try again . . . But do not read, as children read, for fun, or as the ambitious read, to instruct you. No. Read to live.” - Gustave Flaubert

Just what is ‘close reading’, anyway? writingslowly.com