Being human is a trend now.

According to the Mintel Global Consumer Trends Report for 2024:

“Today’s rapidly advancing AI-powered technologies seem to be on track to outpace human output. While consumers and businesses learn to balance the use of this emerging technology, consumers will begin to appreciate what makes humans so unique. A new ‘human-as-premium’ label will emerge, giving greater influence to artisans who can take on the creative spirit that exists outside of an algorithm. As the collective memory of a pre-tech world grows more distant, nostalgia will appeal, even to younger generations that only know the conveniences of a digitised world. From this will rise services that teach human skills like self-expression and focus on how to connect with fellow humans.”

🐙 Octopus intelligence is intriguing. Having read Ray Naylor’s The Mountain in the Sea 📚, I now want to try Other Minds: The Octopus and the Evolution of Intelligent Life by Peter Godfrey-Smith. I’d also like to read Children of Ruin by Adrian Tchaikovsky, which has a somewhat similar theme.

I really enjoyed the latest micro.blog photo challenge, both taking part and seeing all the great photos you people posted. As ever, there were some very imaginative responses to the daily prompts.

Why not check out the photo grid? My own little photo wall is also open for viewing.

As online search declines (thanks Google 😖) more people should know about it the discovery tools on micro.blog. They’re seriously useful.

📷 Day 30: hometown

📷 Day 29: drift

Is the Web reconfiguring itself again?

Is the web falling apart?, Eric Gregorich wonders.

Meanwhile Manuel Moreale is confident that the web is not dying.

I agree with both of them. These views aren’t contradictory. Falling apart is what the Web does best. It’s been falling apart since it started, and reconfiguring itself too.

Google search used to control and shape the web. Because everyone just Googled their searches, websites all used Search Engine Optimization in a vicious circle of conformity. But that’s finally changing.

Search gets degraded by advertising greed on one side and AI tools are generating drivel on the other. Both are examples of what Ed Zitron calls the rot economy.

So how can good material rise to the surface?

In part it’s a return to the old ways. Blogrolls and webrings and RSS are having a mini-revival and it’s not entirely mere nostalgia. One-person search engines like Marginalia are having a moment, as are metasearch engines and other ‘folk’ search strategies. I like little experiments like A Website Is A Room.

Here’s my tip: to find interesting books, great quotes, and intriguing podcasts, more people should know about micro.blog Discover!

Photo by Valeria Hutter on Unsplash

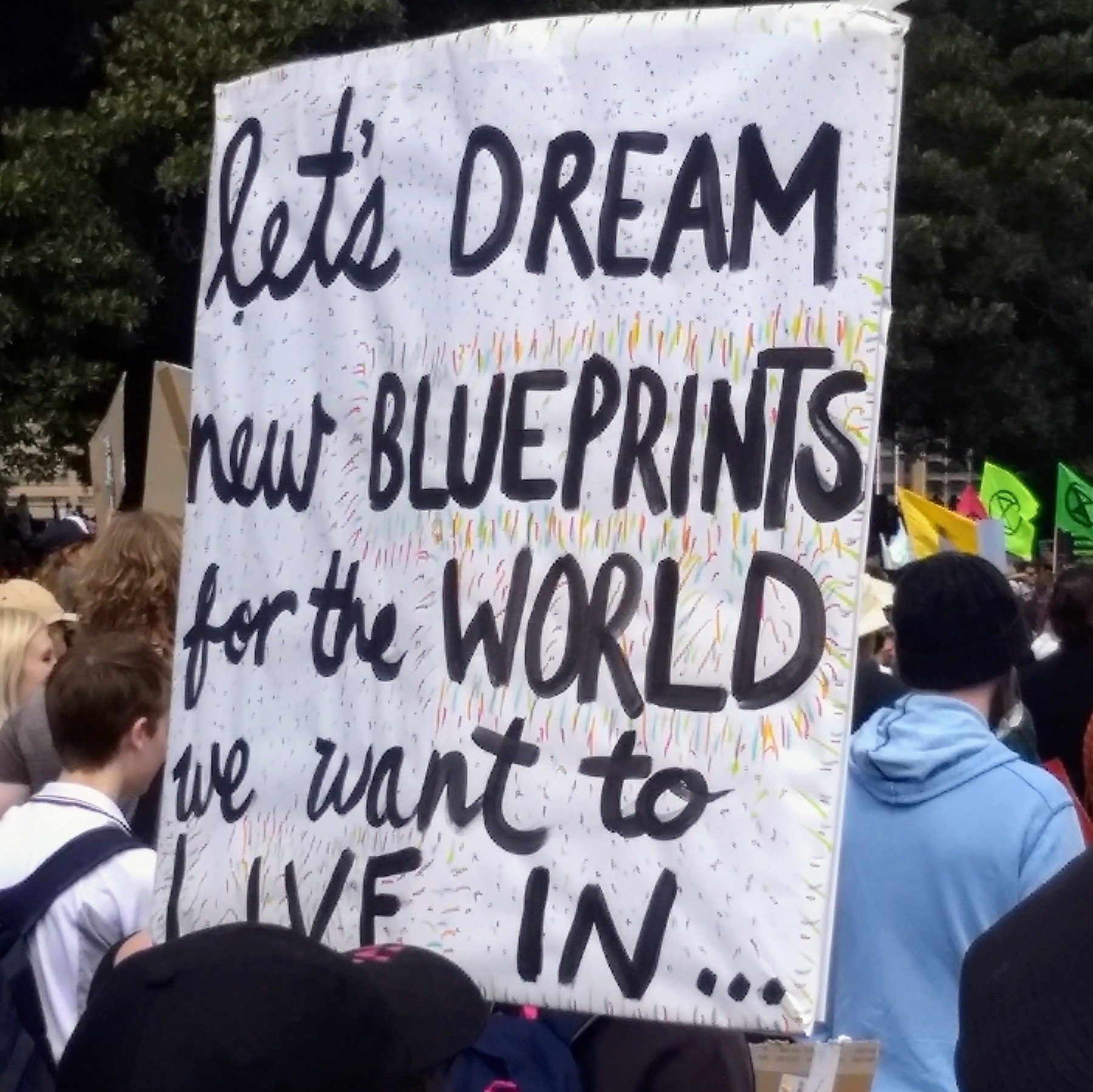

📷 Day 28: Community. Spotted at a rally in Sydney: “Let’s dream new blueprints for the world we want to live in…”

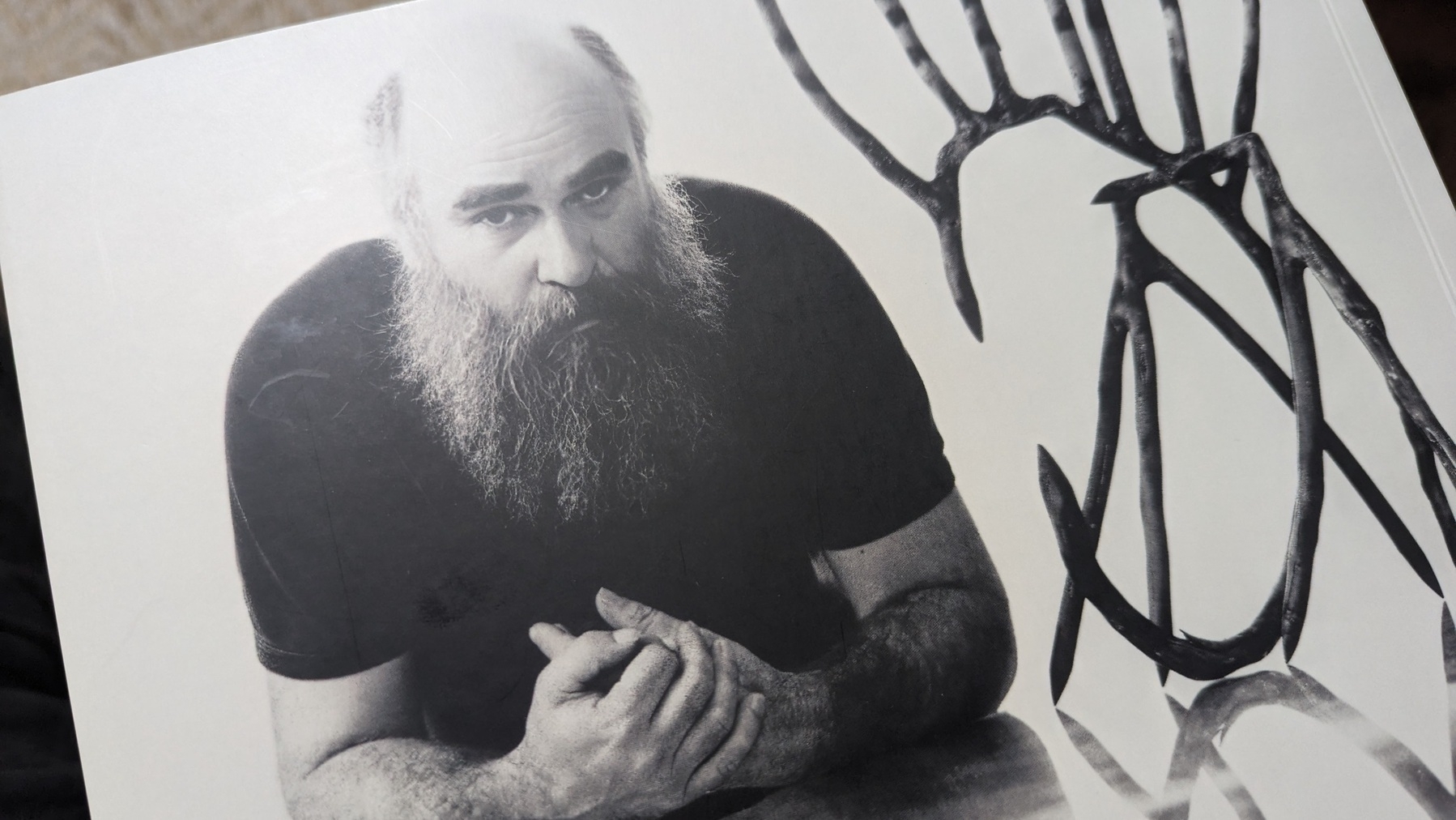

Finished reading: Ian Gentle: The Found Line, edited by David Roach 📚

I’ve posted about this interesting artist previously, because I loved The Gentle Project.

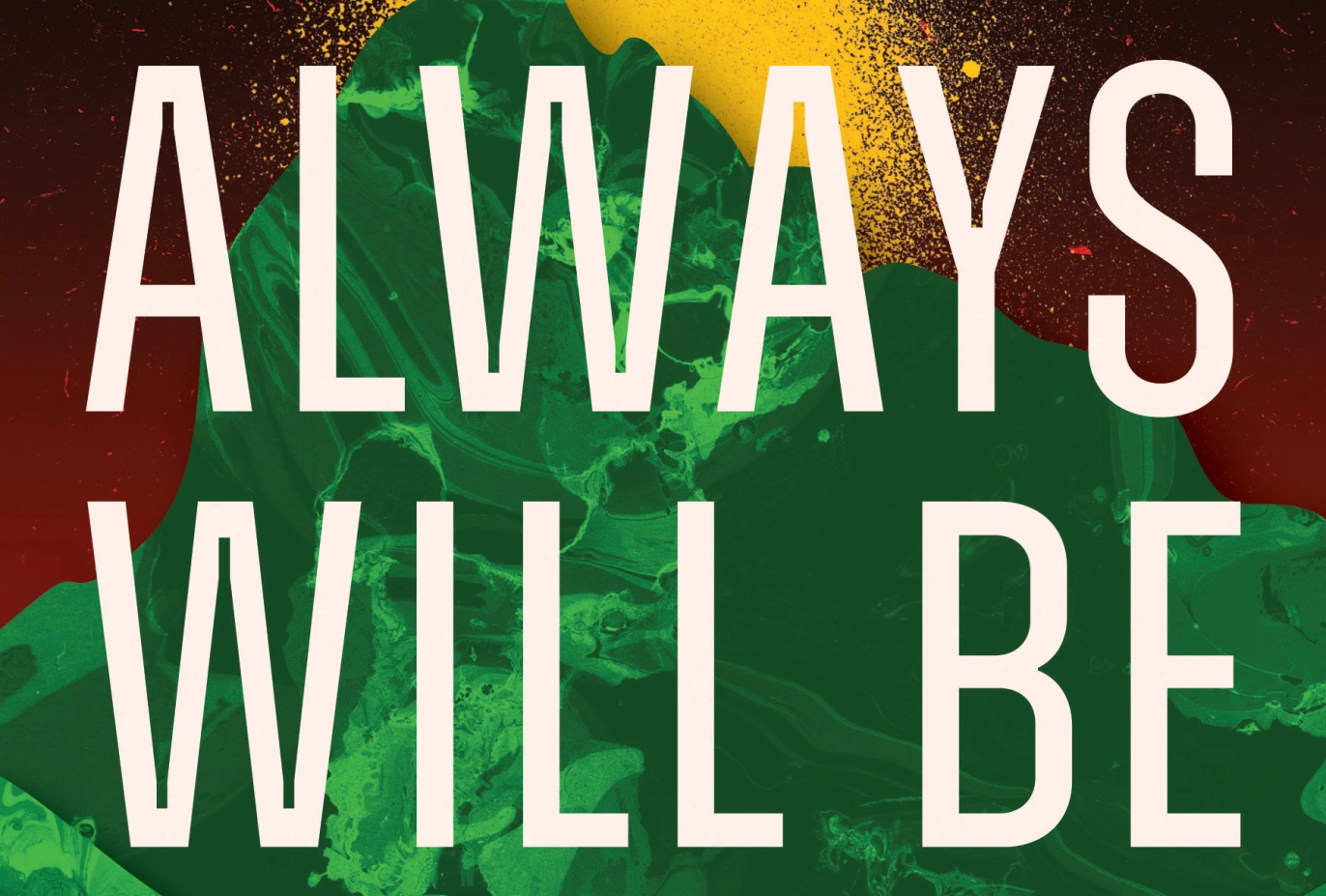

Finished reading: Always Will Be by Mykaela Saunders 📚

These short stories are set entirely in Australia’s Tweed region, but they range over a vast time-frame: from the more-or-less present to the far distant future. I loved the tough optimism. Always will be Aboriginal land - an ideal sci-fi theme.

📷 Day 27: it’s always a lovely surprise to receive a bespoke selection of books in the mail, from the Wild Book Box.

📷 Day 26: critter. It’s a bluebottle, or Portuguese man o’ war. These wash up on the beach, mainly in late Summer and early Autumn.

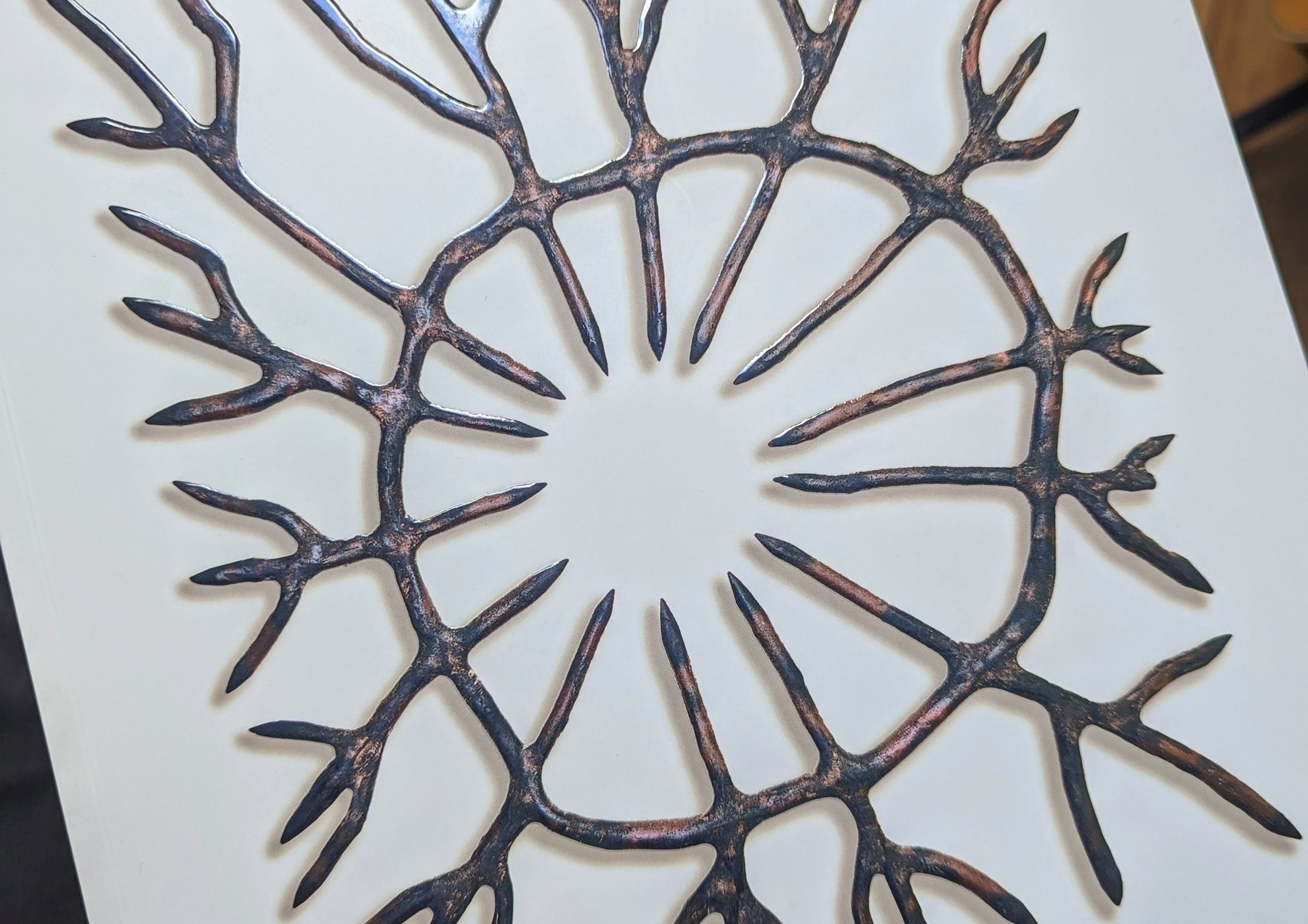

📷 Day 25: spine.

This is ‘Echidna’ by Illawarra artist Ian Gentle.

📷 Day 24: light. I took this shot as we saw in the new year on the beach.

📷 Day 23: dreamy. On the weekend I visited White Bay Power Station for the Sydney Biennale. Reopened after 40 years mothballed!

📷 Day 22: blue. This is the ocean pool at Kiama, NSW.

📷 Day 21: mountain. This is Black Mountain, the unlikely centre of Canberra.

📷 Day 20: ice

Memories of Norway.

📷Day 19: birthday

On my birthday this year I visited an exhibition of the artist Louise Bourgeois. She claimed we’re born alone, but it’s the opposite. We’re born quite literally connected to another person.