Atomic Notes

-

Leonardo da Vinci, whose notes were “a collection without order”;

-

Leibniz, who created a haystack of notes (oh, and calculus);

-

Aby Warburg, who suffered from Verknüpfungszwang - the compulsion to find connections; and

-

Hermann Berger, a Swiss author who wrote a novel about a Zettelkssten (two actually) but didn’t publish it.

-

Then there’s cultural theorist Walter Benjamin, who invented a whole new methodology for his Arcades Project, which he didn’t finish. Wikipedia. He’s certainly a candidate for unqualified posthumous ADHD diagnosis.

- Austin Kleon, interview on The Echoes Podcast, 10 June 2025.

Use case for the Zettelkasten

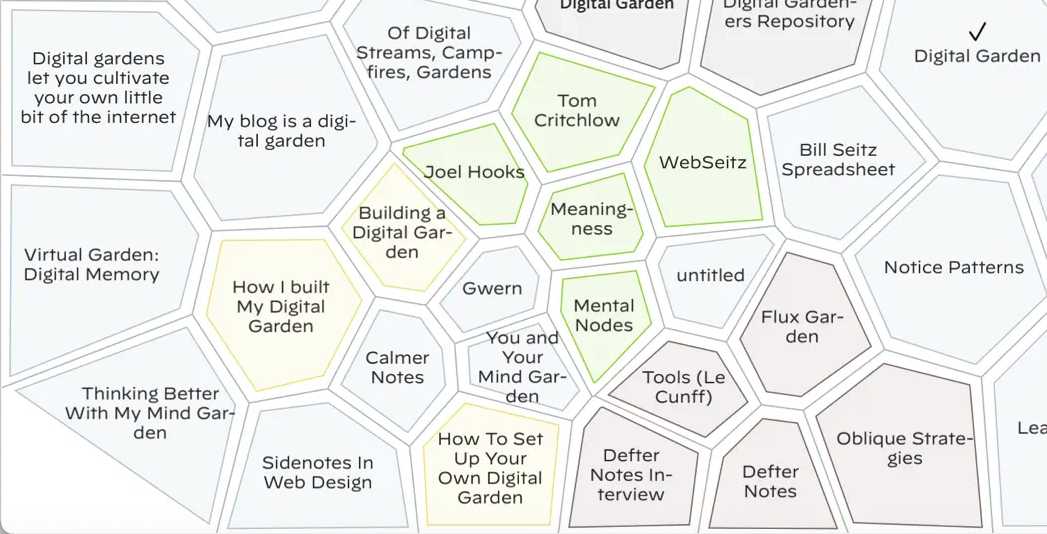

Why use a Zettelkasten? Why indeed? Geeky online legend Gwern was rather negative:

Most people simply have no need for lots of half-formed ideas, random lists of research papers, and so on. This is what people always miss about “Zettelkasten”: are you writing a book? Are you a historian or Teutonic scholar like Niklas Luhmann? Do you publish a dozen papers a year? Are you the 1% of the 1%? No? Then why do you think you need a Zettelkasten?

He argued that tools for thought don’t actually aid thought and that the obviously useful alternative is ‘systems that think for the user instead’.

Wait, what? Systems that think for the user?? I disagree with this very strongly. Sure, it’s true that as they stand, ‘tools for thought’ are no substitute for humans putting in the effort. But I don’t see that as a valid criticism.

The human effort is the part that matters. The effort of thought is actually a feature not a bug. Human thought is preferable to AI computation not because it’s more efficient (although it very often is) but because it’s more human, and humans warm to the activity of other humans.

For instance, in early 2025 a Lithuanian explorer attempted to cross the Pacific Ocean in a one-man rowing boat. He made it to within 740km of the Australian coast, when he was assailed by a cyclone and prevented from sleeping for several days straight. In extremis he finally set off his SOS beacon and the Australian navy came to rescue him, despite the 16-metre-high swells they had to brave. The adventurer only just made it out alive. Returned from the dead, back on shore and reunited with this wife in a photogenic moment he sank to his knees as she embraced him.

Now this was all very interesting, despite the fact that the very ocean water that was trying to capsize him routinely crosses vast distances with no problem. No one cares about the brine, no one feels for its plight and the media never report on its travails. Did you ever see a headline like this:

“Alone and exhausted, a desperate ocean wave makes it gratefully to shore”?

No you didn’t. That was a rhetorical question. Human interest stories work because it’s humans that we’re interested in.

*Won't someone think of the poor wave?*

*Won't someone think of the poor wave?*

Improbably, this wasn’t the only Lithuanian paddler to survive a run-in with Australian waters in recent years. The previous year a Lithuanian kayaker slipped into some rapids on Tasmania’s Franklin River, where he was jammed between rocks and pinned down by a flow of 13 tonnes of water per second. Again, he was the subject of a daring and extreme rescue. Meanwhile, no one thought twice about how the water felt.

And no one cares either when it’s AI that’s supposedly doing the ‘thinking’. It’s inanimate. But they do care quite a lot about a solitary Lithuanian in mortal danger. And so on.

I’ve never visited the Franklin River, which this photograph I took in New Zealand clearly illustrates.

I’ve never visited the Franklin River, which this photograph I took in New Zealand clearly illustrates.

Getting back on track, the thought that goes into making notes matters, quite simply because thought just does matter. Conversely, when ‘systems think for the user’, well, whatever that is, it’s not thought.

But beyond this, I can’t help wondering why we need to justify at all a practice so basic as simply making notes and linking them. My half-formed thoughts might not be as good as Gwern’s (OK, they definitely aren’t), but at least they’re my half-formed thoughts.

In a co-authored conference paper, Mark Bernstein, creator of the Tinderbox app, makes what ought to be an obvious point:

“It may frequently be the case that we ourselves do not know the ultimate uses of our notes, yet still find note-taking rewarding.” - Bernstein et al., 2025, Back to the Information City

Reflecting on Gwern’s dismissal of the Zettelkasten approach, I’m reminded of self-help guru Oliver Burkeman, who had a different criticism to offer. He said he had tried a Zettelkasten but found it too organised. That got me wondering, how much mess is just enough?

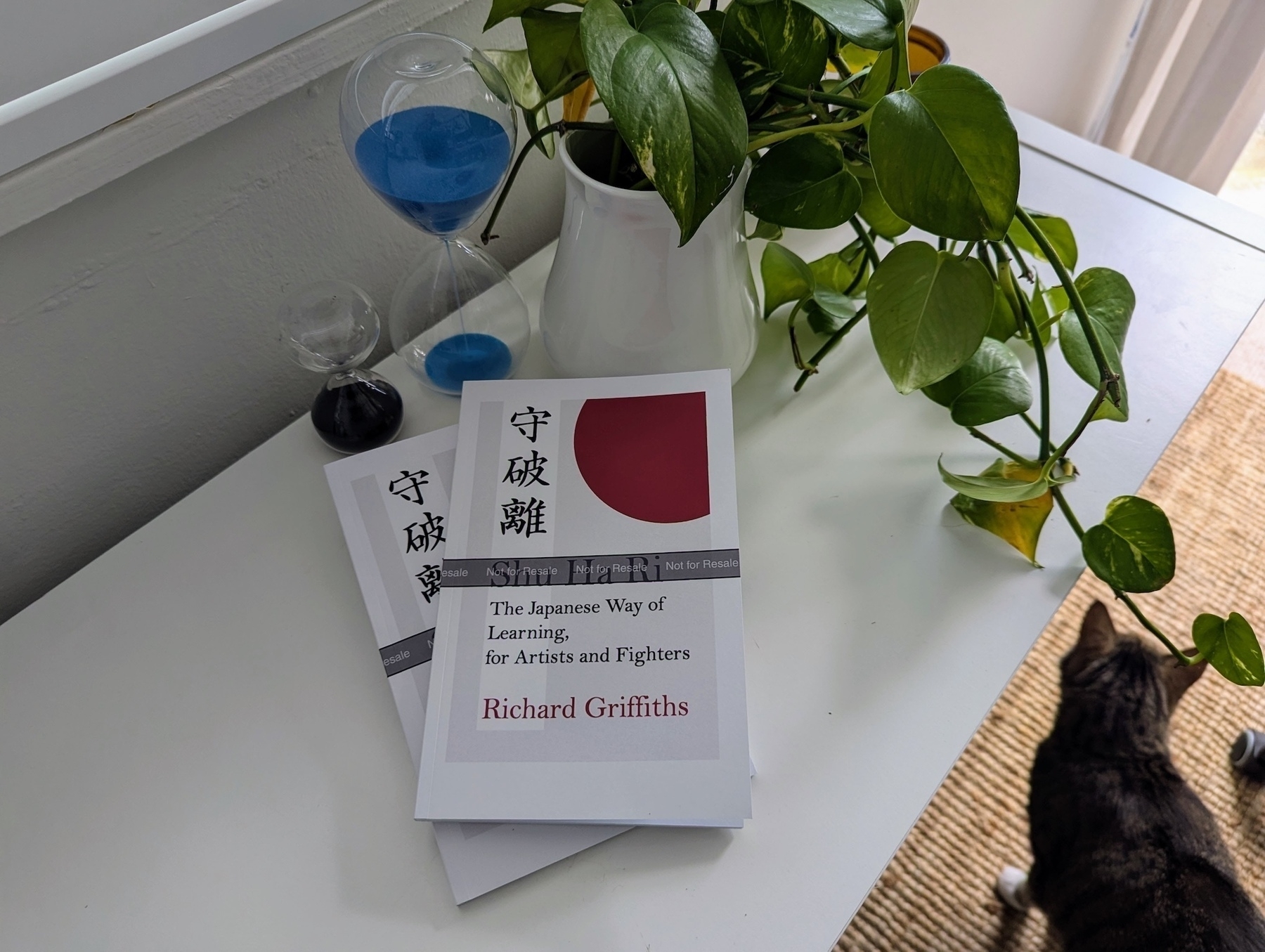

For what it’s worth, I’ve found the Zettelkasten approach very practical and quite productive, despite my not being particularly organised. Here’s a book it helped me write and publish: Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters.

And of course, my Zettelkasten is helping me to carry on Writing Slowly. You can follow the frenetic action with the weekly digest - a blog magically transformed into an email. Amazing!

See also: From tiny drops of writing great rivers will flow.

Reference:

Bernstein, Mark, Silas Hooper, and Mark Anderson. ‘Back to the Information City’. Paper presented at HT 2025: 36th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media, September 15–18, 2025, Chicago, IL, USA. 2025. Preprint PDF.

#Zettelkasten #PKMS #notetaking #toolsforthought #Lithuanian #HT2025

Is there a Zettelkasten method?

Quite a few people write and speak about the Zettelkasten, a simple way of maintaining a note making system, but is there really any such thing? Some reflections on the seemingly obsolete practice of writing notes on small slips of paper and arranging them so they can be found again.

Open, free and poetic

The Web is 34 years old! Following on from Plenty of ways to write online, here are some really practical resources to help you create your own presence online :

Keeping the Web free, open and poetic.

Old hands will probably find a few useful tips here too.

Oh, and here’s another great big list of useful personal website stuff. Actually, I’m making a note of this for my own ‘going down the rabbit-hole’ purposes:

Resources List for the Personal Web

It’s also easier than ever to publish a book. Check out mine: Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters. And to stay connected, subscribe to the weekly email digest.

*Image source: Public Domain, Wikimedia.

#indieweb #webwriting #worldwideweb #blogging

Plenty of ways to write online

Writing online is more accessible than ever. We can maintain control of our own work by publishing on personal websites while also syndicating content to social media. And as I’ve discovered, it’s also easier than ever to publish a book..

Watch in awe as a fleeting thought becomes a lasting note

I describe in detail how I wrote a blog post and then repurposed it as a permanent note in my Zettelkasten collection. This is the opposite of my usual workflow, where I create publishable writing from my existing notes.

Hot takes on our future with AI

Here are eight ‘hot takes’ on the latest problems, questions and opportunities large language models are giving us. It was going to be just three, but the hot takes are coming thick and fast right now. These links are shared alongside my personal reflections on the impact and future of AI that does your writing for you while cosplaying as a human.

If there's more than one way of seeing, there's more than one way of organising

💬 “Our eyes are built for two perspectives. During the daytime we rely on our cone cells, which depend on lots of light and let us see details. At night the cone cells become useless and we depend on rod cells, which are much more sensitive. The rod cells in our eyes are connected together to detect stray light; as a result they don’t register fine details. If we want to see something in bright light, we focus the image on the center of our retina (the fovea), where the cone cells are tightly packed. To see something at night, we must look off to the side of it, because staring directly at it will focus the object on the useless cone cells in the fovea. The way we see in bright light differs from the way we see in shadows. Neither is the ‘‘right’’ way. We need both.” - Gary Klein (2009) Streetlights and Shadows. Searching for the Keys to Adaptive Decision-making. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

On reflection, more can be said along these lines. Another way of looking at this ‘double perspective’ of human vision is to note that it constantly depends on some kind of accommodation between our two eyes working simultaneously and in concert.

So although vision is actually several processes taking place at once, we insist on perceiving it as one unified process. We can’t help it. We’re made to synthesize. But that doesn’t mean it is one process.

The cat is characteristically ecstatic to see that the proofs of the new book have arrived. Not long now before it’s published!

Update: I did it. Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters is now available. I hope you enjoy it!

#amwriting #booklaunch #comingsoon #nonfiction

💬 On Notebooks and Thinking Better Thoughts

Once we’ve let our thoughts mature for a while, we’ll want to produce something for other people to look at, an artifact.

Exactly so.

As Alan Jacobs says, reading more books and reading books more - they’re not the same thing.

I designed a book in three and a half hours

A while ago, well, quite a long while ago, I designed a book in three and a half hours. Fun, yes, but it wasn’t very publishable.

Now, years later, I’ve finally got round to updating and redesigning the whole thing.

Yes, I’m still writing slowly but I’m excited to say it will soon be available for sale - so watch this space for more information.

I’m unqualified to diagnose the following writers with ADHD but I’ll do it anyway

Yes indeed: confidently diagnosing deceased note-making writers with ADHD, while in possession of no medical qualifications myself, is a temptation I simply cannot resist.

For example I have wondered about:

As I said, it’s interesting, but for now I’ll stop there.

—-

This post started life as a comment on Reddit. If you’d like more from me, but in a weekly email, why not subscribe right now?

💬 “The things that make us different, in the right context are superpowers. You know, Saul Steinberg said the thing that we respond to in any work of art is the struggle of the artist against his or her limitations.”

This makes me feel like there’s an awful lot of wrong context lying about. I guess we all need to find a place where we can thrive, or else make it ourselves.

The original quote is from Kurt Vonnegut’s recollection of a conversation with Saul Steinberg.

#creativity #writerslife #deepthoughts #inspiration

💬 Most attempts at providing computerised tools for writers have thrown out the affordances that previous analogue systems offered, almost without noticing their loss. - writingslowly.com on Ted Nelson’s evolutionary list file.

“Sometimes it’s just nice to know there are other people out there quietly thinking things through.” - writingslowly.com

Don't let your note-making system infect you with Archive Fever

The Zettelkasten note-taking system offers a structured approach to organizing thoughts but might induce “archive fever,” which may lead to an obsession with preservation over actual writing. Here’s how to protect yourself.

📷 Photo challenge day 25: decay.

My worm farm is amazing! By turning waste into compost these little wrigglers perfom a kind of magic.

It’s also a metaphor for my writing process. I don’t worry if the input is rotten. The output will be quite different.

See also: No writing is wasted

Don’t throw away your old notes

Don’t throw out your old notes, even if you feel overwhelmed by them. Here are some helpful ideas on what to do instead.

What to do when you've made some notes: Start writing

The next step after taking notes is to create a finished piece of writing, acknowledging that the first draft may be disorganized but serves as a foundation for improvement.

What I Learned from Bob Doto about Making Effective Notes and Writing a Book

Historian Dan Allosso led a discussion on Bob Doto’s insights on flexible note-taking and writing processes. It emphasised the importance of iterative development and audience engagement. Here are my notes.