The future of the humanities is wide open

The humanities are shipwrecked

The university humanities are an ongoing shipwreck.

According to Zena Hitz, “the life of the mind is dying or dead in conventional institutions.” (Quoted in William Deresiewicz’s article, Deep reading will save your soul ).

And as John Halbrooks observes, “Our university administration clearly sees humanities faculty as a (barely) necessary annoyance, as is the case in most public universities these days. It is all about STEM fields and professional schools and grant money, especially as state appropriations for higher education have shrunk. The only values are economic. "

Image source: Jules Verne, Dick Sand: A Captain at Fifteen. Illustration by Henri Meyer Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, Alan Jacobs commented on how the liberal arts seem to be thriving beyond the universities, just as those institutions continue to shrink their own involvement. He quotes a WSJ book review that mentions the Catherine Project and the Lyceum Movement in the US.

Jacobs observes that a prospective student might find it hard to justify spending many thousands of dollars on a traditional arts degree when so much of the same or similar material is available outside that framework. As a professor at a liberal arts college, he offers a cautious welcome, two cheers perhaps, to the growth of the arts beyond the academy.

Also of note is the French phenomenon of radical philosophers establishing learning contexts beyond the university.

For example, there’s Le Collège international de philosophie, co-founded by Jacques Derrida. And there’s Le Université populaire de Caen, founded by Michel Onfray.

In the US there is Vital Thought, and in the UK The Reading Room, sponsored by Pluto Press. And older experiments such as the venerable and once vibrant Chautauqa movement still exist.

The outlook might be poor in the US, but in Australia applications to arts subjects have gone up, and this increase in applications is despite a massive rise in fees.

I find it unfortunate, sad even, that so much of the discussion about education has revolved around money. William Deresiewicz quotes a student, Matthew Strother, who says, “It’s hard to build your soul when everyone around you is trying to sell theirs”.

Whether it’s the price of the course of study, or the potential return on investment in the form of a well-paid job, or the creation of a compliant worker, why is it all about money and not about human flourishing?

Well, one obvious answer would be that these days it simply is all about the money.

Cracking capitalism at the edge of the academy

Yet a quite different answer to this question appears in the form of sociologist John Holloway’s concept of ‘cracking capitalism’ by abandoning our subservience to ‘abstract labour’:

“The real determinant of society is hidden behind the state and the economy: it is the way in which our everyday activity is organised, the subordination of our doing to the dictates of abstract labour, that is, of value, money, profit. It is this abstraction which is, after all, the very existence of the state. If we want to change society, we must stop the subordination of our activity to abstract labour, do something else.”

And this doesn’t sound quite so radical when you consider that we’re already doing something else, at least for some of the time.

We allocate a significant portion of our lives to activities that place financial considerations firmly in the background rather than the foreground, to pursuits which, in brute economic terms might be, well, uneconomic. We do all sorts of things for which there’s little financial justification.

Immense resources go into the sporting life in all its forms, for example, and in return it provides health, meaning and community. No one says: “we’re promoting youth sports so children will be fit for the modern workplace”. But if that’s so, why are they promoting youth sports? No one really asks. They just go ahead and promote sports. The sports club exists in order to promote sports, not the other way around.

As Latin scholar Justin Stover said in 2017, when he claimed that there is no case for the humanities, “Golfers do not need to justify the rationale for hitting little white balls to their golf clubs”. Instrumentalist rationality is nowhere to be seen. Or else it’s the inverse of university rationality. The golf club exists to enable the playing of golf, in a way that the university does not now exist to enable learning (learning, like golf, is a ‘social object’ with multiple benefits).

So why not approach the arts and humanities like this too?

No, seriously, why not?

Maybe it’s a category error. Holloway assumes his readers might not like a subservience to ‘abstract labour’, but perhaps the leadership of universities does actually want exactly this subservience. Stover claims that without the humanities, the university simply won’t be a university, but perhaps by now the very definition of the term has been transformed. In the old days the cynics used to say that Harvard was large investment fund with a university attached. But the real situation is far worse than that. As neo-liberalism metastasised further into financialisaton, the universities, like every other institution, changed their purpose, became mechanisms whose primary purpose is to establish relations of debt.

You may come away with a degree. You may as a result become more employable in the job market than you otherwise might have been. But these are not certainties. There is however one certainty: you will leave university with a substantial debt, a student loan which will follow you into your distant future like a hound of hell.

This matters because it turns institutions that only exist as universities provided they include the study of the humanities, as Justin Stover claimed, into institutions that only exist as universities provided they can encumber their customers with a significant long-term loan.

The cyberneticist Stafford Beer coined the unwieldy acronym POSIWID , meaning that the purpose of a system is what it does. And in that spirit we can observe that the purpose of higher education is to create student loans. In fact, since many don’t graduate, it creates many more student loans that it creates graduates.

Ironically, the advocates of qualitative evaluation by means of quantitative analysis, those whose ‘only values are economic’, will probably deny that this particular quantitative analysis has any relevance. The loans are obviously just a side-effect of the main purpose of the university, they will claim. Yet this is exactly the kind of evasion that Stafford Beer intended to highlight. They would say this, because they got the bulk of the cash.

Now what would it look like if higher education didn’t intrinsically entail higher debt?

Among several examples John Holloway gives of the ordinariness of resistance to abstract labour are the following:

- “the university professor in Athens who creates a seminar outside the university framework for the promotion of critical thought”.

- “the university teacher in Leeds who uses the space that still exists in some universities to set up a course on activism and social change”.

What we do in our leisure time is usually understood as being without economic value (or is extractive, as in watching TV adverts). Leisure is time when workers are not being productive. But maybe there’s a different kind of productivity going on here, following a different logic.

In the world of value, money, profit, Celine Nguyen has some valuable thoughts on research as a leisure activity, a concept she got from Karly W. John Holloway sees ‘cracking’ as “the perfectly ordinary creation of a space or moment in which we assert a different type of doing”.

What kinds of different?

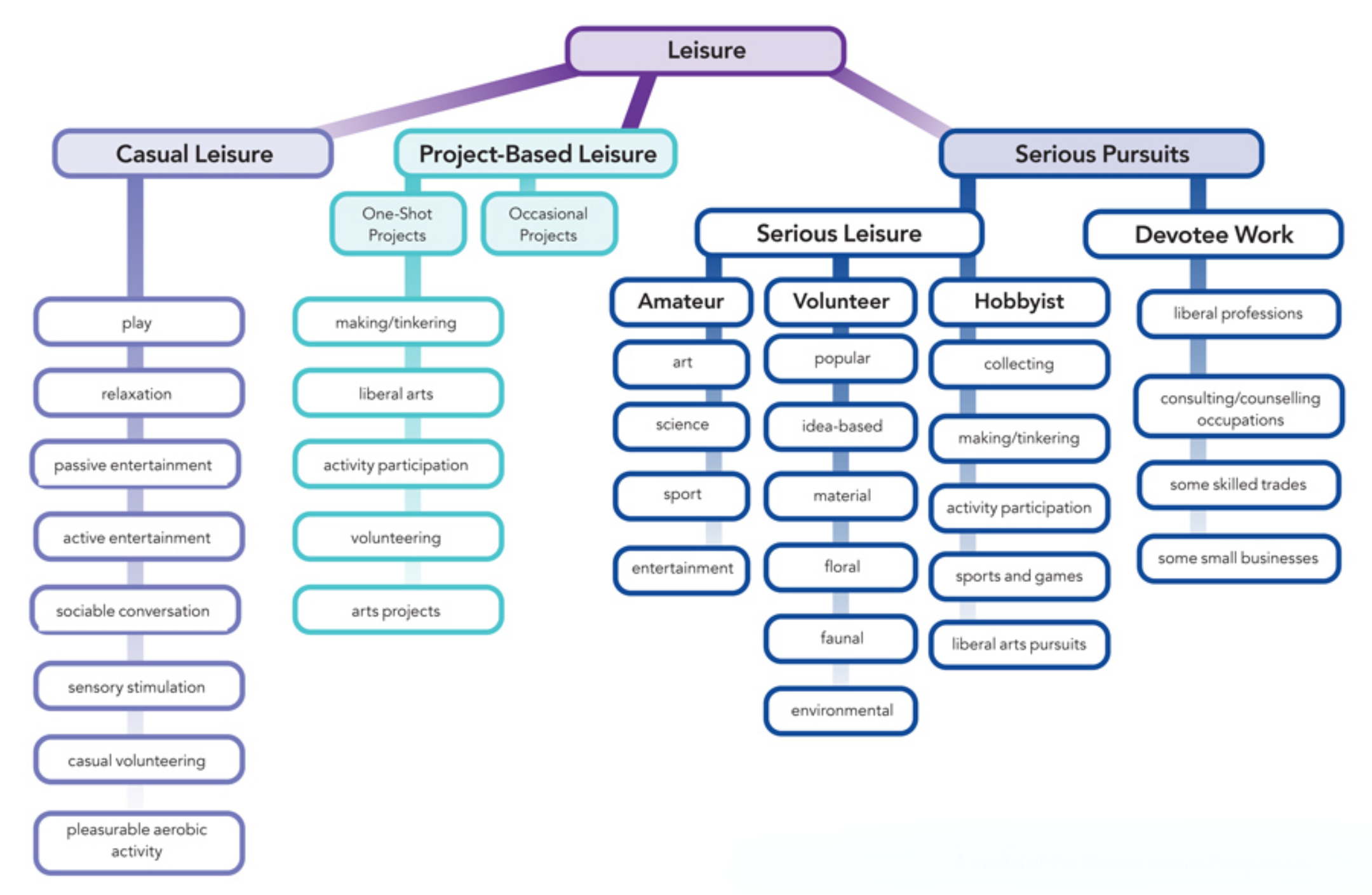

Whether or not you want to change the world, the serious leisure perspective is a framework of analysis that might be useful here. Sure, it’s leisure, but it’s far from trivial.

*Image Source: researchoutreach.org/wp-conten…

Leisure is a serious business

This perspective charts the continuum of activities and approaches that ranges across a spectrum from the entirely casual to the entirely professional. There’s a lot to be understood about the wide regions between these two poles. Recognising the breadth of the field might help clarify the nature of the shifts that are taking place in our time.

Starting with casual leisure, we have passive entertainment such as reading, and active entertainment, such as writing. These are casual because there’s no particular expectation of any skills development or improvement.

Serious leisure, on the other hand, is predicated on taking it seriously (there’s a clue in the name), with a measure of dedication - serious time and effort spent to improve one’s skills and capabilities. Hobbyists and amateurs are both serious about their enthusiasms. The hobbyist differs from the amateur in that the former has no particular relationship with the professional end of the spectrum, whereas the amateur might well have such a connection. For example, the hobbyist might just pursue the activity alongside other hobbyists, while the amateur might also take part in classes and workshops led by professionals.

Beyond the amateur pursuit of serious leisure, the devotee engages in quasi-professional activities. For example, the amateur historian might research and write about local history, but the devotee might also publish it and present talks on the subject, in a manner similar to that of the professional historian. You can probably see that the line between the serious leisure devotee and the professional is not in fact very rigid.

Another way of describing this is that at the professional end of the spectrum, professional work blends into devotee work. Vocational activities might be seen as a kind of commitment to devote one’s working life to very serious leisure. Indeed, there are many professionals who would readily admit that they would willingly do their work even if they weren’t paid for it. What they do is serious, whether it’s called leisure or work, or anything else.

I want to emphasize here the long continuum from casual leisure, through serious leisure, all the way to professional activity and work. Each step along this continuum requires its own institutional context with varying degrees of recognition and membership, and different kinds of gateways and barriers to entry.

It’s amazing, at least to me, how walled off from the rest of the world the academy has become. So much of the institutional structure seems deliberately set up to break any sense of the continuum I’ve been describing between casual, serious and professional. The world of sports would collapse if it behaved like this. So would the music industry, the art world, and many other areas of human endeavour where excellence is valued. The outreach, extension and continuing education efforts of universities, at least in the British and Australian context of which I’m aware, seem a pale shadow of what they surely would be, if only serious leisure was taken seriously.

Looking at the Cinderella-like existence of many university extension programmes, it’s almost as though the pursuit of academic interests for leisure purposes is perceived as a threat to the institution, or an annoyance at best, rather than an opportunity, as though the academic experts are in some kind of competition with the devotees, the amateurs the hobbyists and even with the casual dabblers. Why should this be? Where does this sense of threat come from?

Perhaps employment precarity in an era of rampant casualisation comes into play here. As a senior academic once told me: “The gap between tenured professor and casual taxi-driver is surprisingly small.”

And perhaps status anxiety has something to do with it too. Viewed as a hierarchy with tenured professors at or near the top, casual lecturers near the bottom, just above the undergraduates, and the massed ranks of the leisure enthusiasts so low down as to be beneath consideration, the structure of the higher education sector begins to make sense.

With whole arts and humanities departments facing the axe, or already uprooted, the anxiety makes sense too. It must be hard to enjoy the view from the top of the tree when the entire forest is being clear-felled around you.

Then there is the matter of boundary transactions. Eliel Cohen (2021) documents how educational institutions “must engage in boundary transactions in order to maintain their unique position and identity”, but at the same time, these transactions risk undermining academic boundaries.

The remedy for this is hopeful, but it requires a radical reappraisal of the relationship between the top and bottom of the hierarchy. In fact, it requires the difficult recognition that it’s not a hierarchy at all: it’s an ecology.

Image source: Dick Sand: A Captain at Fifteen by Henri Meyer Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

Towards a healthy academic ecosystem

In a healthy ecosystem, diversity enables cycles of growth, flourishing, decline and regrowth to persist through time.

Similarly, in a thriving educational ecosystem, there is a healthy mutuality between the experts and the amateurs, between professionals and dabblers, that has been largely lost, but that stands a chance of growing back again. Once the largest trees have been felled, the weeds move in to protect the ground. That’s how I see the proliferation of history podcasts and YouTube channels at exactly the same time the history and literature departments are being pulped. The twilight of the Humanities at a university level has nothing to do with the burgeoning level of interest in the humanities among the general public.

I mentioned John Halbrooks and his gloomy view of the humanities. He might be gloomy but he’s not sitting around waiting for the axe to fall. Instead, he’s doing his part in re-connecting the academy and the general public, refurnishing the public intellect. His Substack newsletter, Personal Canon Formation, relates closely to an undergraduate course he’s teaching - on writing newsletters. He’s teaching humanities students to connect to a wider world that is interested and enthused by the humanities, and he’s leading by example.

So if you’ve read this far and are still thinking it’s all very well ignoring the money, pretending we’re changing the world by reading critical theory or Nineteenth Century novels, but that will just end in bankruptcy, here’s some news for you: The Chinese education sector is rapidly shifting towards what it calls the ‘silver economy’.

The silver economy involves seniors, a fast-growing sector of the population. In fact over the next decade about 300 million Chinese people will enter the retirement phase of their lives. With this huge demographic shift in mind it seems reasonable to predict massive financial benefits for education-providers who diversify, or else switch entirely to the older end of the market. This will be a difficult shift for the higher education sector in the English-speaking world, because the emphasis for many centuries has been so firmly placed on younger students. After all, each year there’s a new crop (of future debtors)!

But since, as we’ve heard, “the only values are economic”, and since higher education exists not to challenge the logic of capital but faithfully to reproduce it, I fully expect education providers sooner or later just to follow the money.

—-

Did you know you can subscribe to a weekly email digest of all the Writing Slowly posts?

—-

References

Cohen, Eliel (2021). “The boundary lens: theorising academic activity”. The University and its Boundaries: Thriving or Surviving in the 21st Century 1st Edition. New York, New York: Routledge. pp. 14–41. ISBN 978-0367562984.

Alan Jacobs, we need to spend a lot of time imagining the humanities without the university.

Zettelkasten Forum discussion on self-improvement.

Serious leisure: What constitutes optimal leisure?.

William Deresiewicz, Deep Reading will save your soul.

Further reading

Zina Hitz, Lost in Thought: The Hidden Pleasures of an Intellectual Life (2020) Jeffrey Bilbo (ed) et al. The Liberating Arts. Why We Need Liberal Arts Education. Plough Publishing House, 2023. ISBN: 9781636080673

Michael D. Smith, 2023. The Abundant University. Remaking Higher Education for a Digital World. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN: 9780262048552 P.xxii. A podcast interview with Michael D. Smith [New Books Network] (https://newbooksnetwork.com/the-abundant-university)

Dirks, Nicholas B. City of Intellect: The Uses and Abuses of the University. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, (2023). ISBN: 9781009394444 P. 296.

See also: Detweiler, Richard A. The Evidence Liberal Arts Needs: Lives of Consequence, Inquiry, and Accomplishment. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2021.

Hayot, Eric. 2021. Humanist Reason. A History. An Argument. A Plan. Columbia University Press. ISBN: 9780231197854

- A podcast interview with Eric Hayot New Books Network

Merrifield, Andy. 2018. The Amateur: The Pleasures of Doing What You Love. First paperback edition. London New York: Verso. ISBN: 9781786631077

Rybczynski, Witold. Waiting for the Weekend. United Kingdom: Penguin Books, 1992. Reimagining Higher Education in the United States McKinsey

DAOs as University Replacements: A Thought Experiment. Kassen Qian

Colleges Are Dying, Long Live Higher Education. How the death of institutions shouldn’t mean the demise of personal development. Matt Klein and Robert Cain

The Catherine Project. Zina Hitz. Plough, May 23, 2022.