The Spiral of Mastery: Why the Greatest Experts Are Serial Beginners

The greatest experts aren’t afraid of starting again

Apparently, my tennis is rusty

Here in Australia the Christmas holidays take place in mid-summer, and my family spent a few days at a house with a tennis court. It was an amazing opportunity, for which we were hardly prepared. I hadn’t played in years. One family member had barely held a racquet before. But we all shared the same problem: our serves were terrible. The ball hit the net, or it veered wildly off court. The serve seemed like some monolithic, unreachable skill you either had or you didn’t.

The view from the court — that was amazing, but the tennis, to say the least, wasn’t flowing.

That was until someone suggested we break it down: grip, swing, ball toss, contact. We stopped trying to play and started drilling. Within a short while, the court was alive with movement and we were laughing instead of frowning with effort. Our natural talent hadn’t changed; it was just that our willingness to break the seemingly impossible into achievable parts made it somehow seem doable. And after a short while, it actually was doable. We were delivering serves that made it over the net, that you could also imagine returning.

This experience was a reminder that expertise is hardly ever about making a single massive effort to achieve something that seems impossible. You don’t get good at tennis all at once. Playing the game well is really a whole portfolio of tiny pieces of expertise you have to master one by one and piece together smoothly before you can reach actual proficiency. And even when you get there, that’s not the end. There’s always something, some element of your play, you can improve. Is mastery a destination to reach and then enjoy forever? No. It’s more like a spiral that requires us to return to the beginning again and again of a long series of micro-skills.

Experts Get Stuck Because They Stop Looking

But you can reach a point where it’s hard to see how to improve, or if it’s even worth it. For creative practitioners, there may come a moment when the work loses its spark. You’re competent, maybe even accomplished, but something vital has drained away and it feels like you’ve reached the plateau of your expertise. You can’t see what to improve because you’ve stopped looking. So you repeat what works because it works. Meanwhile, beneath the surface, your joy is slowly curdling into staleness.

There’s a cultural dimension to this trap. Experts aren’t supposed to feel like beginners. So we stay on this plateau, defending our position rather than climbing higher. The writer Ernest Hemingway understood this. Despite his Nobel Prize and decades of acclaim, he insisted: “We are all apprentices in a craft where no one ever becomes a master.” He wrote to a friend of his that “dopes would say you’ve mastered it”, but he continually felt like an apprentice.

How Do You Actually Get Better?

In their book Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise, Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool show that expertise is built through deliberate practice: the systematic isolation and refinement of specific sub-skills.

Take that tennis serve we all struggled with on holiday. Total proficiency is really just a messy stack of mastered micro-movements. You have the grip and the swing mechanics, but also the ball toss, the contact point, and the tactical intent. A player gains expertise not by playing endless matches but by drilling these elements until they’re second-nature. For writers, the equivalent sub-skills are less obvious but they still exist. It might come down to the rhythm of dialogue or the way a transition sentence functions, or to opening hooks, sensory detail, and the painful art of compression. Drilling these exercises might feel artificial because to an extent it is. But the artificiality is exactly what creates the conditions for focused improvement.

I found the map of learning: Shu Ha Ri

The traditional Japanese framework, Shu Ha Ri, maps this growth as a recurring cycle, a sort of beautiful, never-ending loop that keeps things interesting no matter how far advanced you become. In the Shu phase, you just dive into the work. It’s this foundational, deeply immersive period of copying a master’s handwriting or holding a racquet in that specific, stiff posture that eventually starts to feel like it’s natural (please don’t challenge me on this — as I say, I still can’t actually play tennis). Early on you’re essentially acting as a mirror, reflecting something great until it sticks.

Eventually, you move into Ha, the breakout phase. This is where the tinkering starts. It’s the time when you really start to play. You begin questioning the rules and adjusting your grip, or just messing around with sentence rhythm to see where the tradition ends and your own unique voice begins to shine through.

Then there’s Ri. In this Zen-like space, the rules have been digested so deeply they just… click. The skill happens through you rather than by you, which is a pretty incredible feeling when you finally hit that flow. I certainly haven’t reached this level with tennis, but I have had such moments while playing squash. It’s not so much that you’re playing the game as that the game is now playing you. But the best part is when the top of that mountain reveals a much bigger, sun-drenched one hiding right behind it. You’re invited back into Shu. The master becomes a student again, starting over with a fresh sense of humility and a genuine, open-eyed curiosity for what’s next. The danger is that as an accomplished expert it all gets so serious that you might forget you can go back to the start, you can still play, you can have fun.

You can pivot from expert back to beginner

If you look, you can sometimes see this same recursive loop even at the top of the pop charts. Here’s a well-known example: Taylor Swift during the pandemic. She’d spent a decade building her massive, glitter-cannon “pop industrial complex.” Then, suddenly, she retreats. She ends up in a flannel shirt, recording folklore in a bedroom, where she’s obsessing again over the fragile mechanics of acoustic storytelling like she’s still a teenager. She had to junk the “superstar” persona if she was going to rediscover the songwriter underneath.

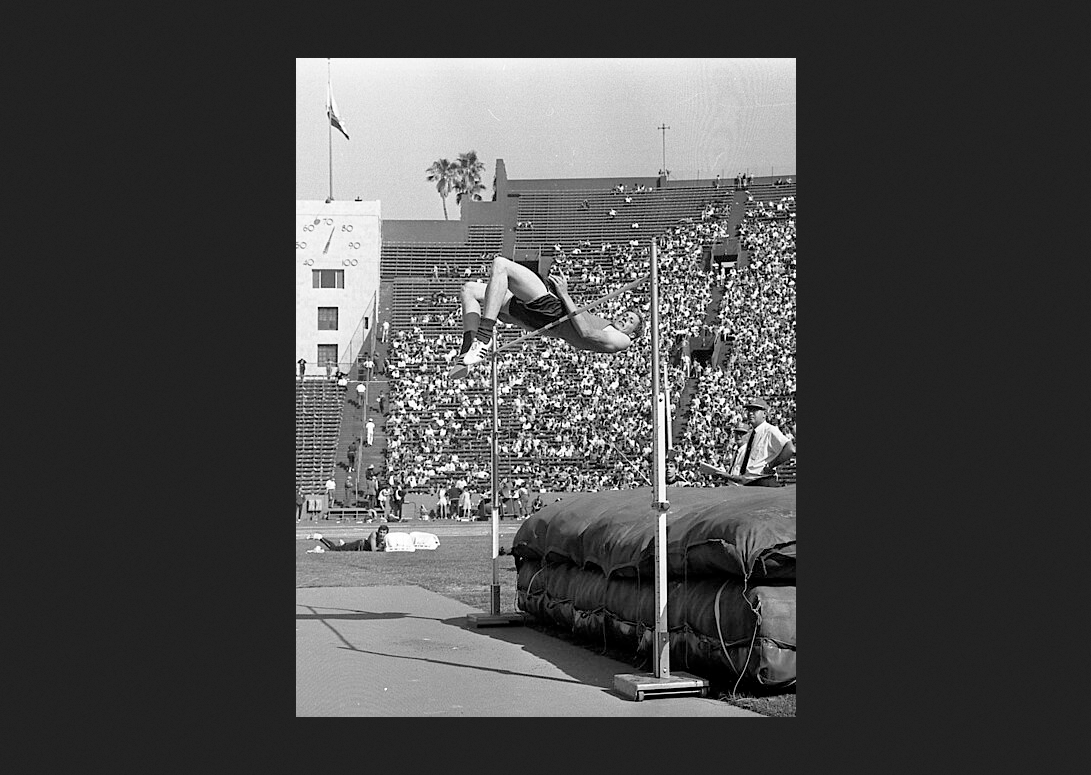

But it isn’t always about these polished pivots from glossy stars. There’s also Dick Fosbury at the 1968 Olympics. Before he showed up in Mexico City every “expert” high jumper on the planet was using the barrel-roll technique. This was basically a face-down belly-roll over the bar that everyone agreed was the limit of human potential. They’d already reached the end of what a scissor jump could achieve and now the barrel-roll was pretty much the rule.

Then Fosbury turns up and decides to jump over the bar head-first and backward instead.

It looked absurd. Here was this gangly young engineering student with mismatched running shoes, who looked like a camel on two legs, as the papers said at the time.

During his Shu phase of figuring it out, he was probably hitting the bar with his neck, landing on his head, and looking like a total amateur while everyone else was doing the proper barrel-roll technique. He had to be willing to look like a flop on the world stage just to prove that the experts' way of jumping was actually just a false ceiling that he could break through. If you watch the old footage, you can see way he has to psych himself up, then the hesitation in his run-up. There’s an electric, shaky moment where he has to choose to trust this new, unproven movement over the mastery he was supposed to have.

Backwards and head-first? It turned out not to be a flop at all. Instead he’d perfected the world-beating Fosbury Flop which almost everyone has used or adapted ever since. But this wasn’t magic. The reality is they’d only recently introduced deep foam mats for a safe landing. You can see this progression in a youtube video called Men’s high jump through the years! Fosbury saw this as an opportunity to become a beginner again, to try something new, and he took it, and it worked.

High jumper Dick Fosbury clearing the bar during 1968 Olympic trials at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Los Angeles Times, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Then, going back to pop, there’s the singer PJ Harvey. By 2007, she could play a rock guitar better than almost anyone alive. So, naturally, she decided to stop. She sat down at a piano, an instrument she barely understood, and forced herself to write the album White Chalk. If you listen to that record, you can hear the ghost of the beginner in it; there’s a kind of haunting, shaky tension, perhaps because her fingers don’t quite know where to go.

In an interview she said, “the great thing about learning a new instrument from scratch is that it […] liberates your imagination.” But I suspect she became a novice on purpose because she knew the “expert” version of herself was running out of things to say. And that’s not all. During the White Chalk tour she started performing on autoharp, another instrument she hadn’t perviously been known for.

You can see both instruments on this Youtube video from the time. PJ Harvey - KCRW 2007

PJ Harvey performing live at the Royal Festival Hall in London, United Kingdom on September 27, 2007. Ella Mullins, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Beginner’s Mind

Shunryu Suzuki, the Japanese monk who brought Zen to Northern California, noted that “in the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.” It’s an interesting way of looking at the world.

Execution requires certainty, the ‘few possibilities’ of the expert. But learning thrives on an open-ended sense of wonder, the ‘many possibilities’ of the beginner. Shoshin (Beginner’s Mind) is really just an intentional suspension of ego. It means looking at a weak sub-skill with total openness, gently setting aside that heavy, defensive armour of past achievement we all carry around. In the real world, this looks like a novelist with multiple published books happily sweating over a basic copywork drill. It’s an established painter returning to the simple magic of primary color-mixing, or a senior developer diving into a new language with the same enthusiasm they felt as a total novice. It’s Taylor Swift going back to basics; it’s Polly Harvey learning a new instrument live on stage; it’s Dick Fosbury attempting entirely the wrong kind of jump.

“When we have no thought of achievement, no thought of self, we are true beginners. Then we can learn something. The beginner’s mind is the mind of compassion. When our mind is compassionate, it is boundless… The most difficult thing is always to keep your beginner’s mind. … This is also the real secret of the arts: always be a beginner” - Shunryu Suzuki, Zen Mind, Beginners Mind: Prologue.

This openness is how you get the spark back. The plateau can sometimes dim the spark that made you pursue this path in the first place, but you can always find it again. To counter that staleness, you just move back into the learning zone. You embrace the risk of failing, a risk which is really just a part of the adventure, and you adopt that open, beginner’s gaze.

Where Do You Start?

Our tennis serves were still inconsistent after that Christmas holiday experiment. Our footwork was a joke. Actually I don’t think we even had anything you could properly call footwork. But still, the court felt alive. Breaking the skill down into its basic components was the thing that killed the frustration and let the joy back in.

If you’re not sure where to start with improving your writing, try this: Look at your last five finished pieces. What do they all avoid? What scenes do you consistently skip or rush through? That avoidance is a signal that this area can use some work. It might be action scenes or emotional confrontation. That’s your sub-skill.

Right now, pick one sub-skill you’ve been avoiding. Not your whole practice. One component. Dialogue attribution. The first sentence of a scene. If you’re an artist, maybe it’s colour mixing. Then set a timer for 15 minutes and drill only that. Don’t worry about the “big picture.”

Just wade, waist-deep into the spiral of continuous learning and let the flow take you.

Further Reading:

- Peak by Anders Ericsson (the science of deliberate practice).

- Big Magic by Elizabeth Gilbert (on creative courage). I wanted to dislike this but actually I loved it.

- Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Shunryu Suzuki (the original text on shoshin).

- A Life in Zen (an article about Shunryu Suzuki).

- Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters (my own exploration of this framework