Is there a Zettelkasten method?

Quite a few people write and speak about the Zettelkasten, a simple way of maintaining a note making system, but is there really any such thing? An online forum comment drew my attention, since it captured something I’ve been thinking about for a while:

“I have come to the conclusion that there is no such thing as a method. The very adjective is a mistake. What exists are a few very general guidelines, essentially revolving around the idea of atomic notes and some form of connection between them. I am not saying this as a criticism of the method or anyone. I have been using “the method” since 2020 and appreciate zettelkasten.de. But there is no method. There is not much to write about “the method” as if it were something beyond those two guidelines.” - u/Magnifico99 on Reddit.

Here are my thoughts and I’d like to know what you think.

There’s no single method, but many

“I have come to the conclusion that there is no such thing as a method… What exists are a few very general guidelines… But there is no method.” - u/Magnifico99 on Reddit.

I really agree with this. There is no single ‘method’. Instead there’s a seemingly obsolete practice of writing notes on small slips of paper and arranging them so they can be found again. Then there’s the digital version of this, which differs from how most note-making apps expect their users to do things.

“What exists are a few very general guidelines, essentially revolving around the idea of atomic notes and some form of connection between them.” - u/Magnifico99 on Reddit.

Well, yes, that’s pretty much it. At any rate, there’s not all that much more to it than that. And I appreciate a minimal approach to making notes.

It’s not a method, but an ‘approach’

I usually employ the phrase Zettelkasten approach. That’s because there clearly isn’t just a single Zettelkasten method. The German sociologist Niklas Luhmann, unwitting patron saint of contemporary Zettelkasten discussions, kept two different Zettelkästen, and everyone else who ever made notes on cards also did it a bit differently from everyone who was doing something similar. I’ve read several 19th and 20th century manuals on writing and note writing - and they all prescribe slightly different approaches, which are all a bit different both from how Luhmann did it and from how most people do it now.

We can experiment with writing notes

But this fuzzy definition isn’t a weakness, it’s a strength. It means the field is wide open for us to experiment and to discover and share what works for us, each of us, guided, but not constrained, by a handful of simple principles.

I see the Zettelkasten in the context of what science historian Hans-Jörg Rheinberger calls “epistemic things” (1997). By discussing the Zettelkasten, we’re actually engaging in the process of creating it 1. Conversely, if ever the conversation stops, that’s when the concept is over. As the Russian literary theorist Mikhael Bakhtin (1986) said,

“If an answer does not give rise to a new question from itself, it falls out of the dialogue”.

But isn’t it a waste of time?

“For a few years now, I have not been able to read anything about Zettelkasten on the internet without clearly feeling that I am wasting my time or indulging in some form of entertainment."- u/Magnifico99 on Reddit.

Despite writing quite a lot here about note-making (sorry to waste your time, dear reader), I agree with this view too. Since the basic guidelines are simple, there’s only so much to be said about them before confusion ensues.

In particular, I’m frustrated by a ballooning of idiosyncratic vocabulary. For example, ‘evergreen notes’? This is kind of helpful, though it seems to be conflating note-making with journalism. For journalists an evergreen article is one you can write at any time of the year and publish later, since it won’t get old. It’s what the newspapers publish when all the journalists are on holiday around Christmas and New Year.

Andy Matuschak reuses this concept for his evergreen notes, to describe something slightly different: a note that stays fresh because it can always be added to. I don’t usually add to my notes. Instead I resolve this differently - not by editing and updating my notes, but by writing new, linked notes, so I can clearly see the evolution of my thought over time.I’m also a little frustrated by the proliferation of supposed note types. What’s the difference between a ’fleeting note’ and a ‘permanent note’?

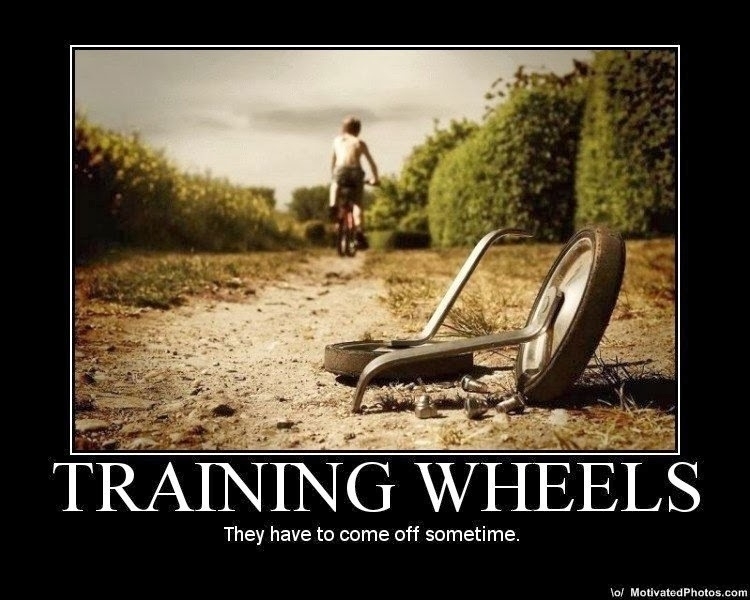

These concepts are like training wheels on a bicycle. They’re useful until you don’t need them, but as with training wheels, there’s a possibility they may impede learning, for some people.

I’m even more frustrated with all those YouTube videos and AI-generated articles purporting to come from helpful experts but actually just regurgitating the previous videos and SEO fodder.

It seems like everyone who ever heard of the Zettelkasten approach has also made a YouTube video or ten about it. And if you look at the chat bot marketplaces you’ll see that there’s an explosion of AI Zettelkasten ‘helpers’ that all offer various half-baked schemes for writing all your notes for you. I counted more than 50 before I gave up. It all seems to add up to nothing but a pile of pointlessness.

So where’s the silver lining?

In two words: community and practice. Low-key community, that is, and real-life practice.

Low-key community

Low-key community is one silver lining to all this rumination. There’s a loose assortment of people (on Reddit/zettelkasten, zettelkasten.de, maybe the Obsidian forums and personal knowledge management (PKM) forums somewhere — and even some readers of this very website) who are interested in better writing and clearer thinking. We are using the Zettelkasten approach as a social object, around which to gather and work on.

These people don’t necessarily agree with one another. In fact disagreeing is one key hallmark of a ‘discourse coalition’ (Hajer, 2009), where everyone who talks about the same thing gets to mean something different by it, then argues over the definitions 2. Although this may sound obtuse, it’s actually quite productive. That’s because it’s in the nature of objects of knowledge to be unfinished or unattained - maybe perpetually.

objects of knowledge in many fields have material instantiations, but they must simultaneously be conceived of as unfolding structures of absences: as things that continually ‘explode’ and ‘mutate’ into something else, and that are as much defined by what they are not (but will, at some point, have become) than by what they are. - Cetina (2001: 182).

Not that, but this. Not quite agreeing on the contours of the Zettelkasten approach is evidence that it’s worthwhile (at least for us) to continue to explore the concept. The more you look into it, the more you see.

“objects of knowledge appear to have the capacity to unfold indefinitely. They are more like open drawers filled with folders extending indefinitely into the depth of a dark closet.” - Bennet (2005). Chat GPT made this great image, but for now your job putting handles on drawers appears quite safe.

Real-life practice

The other silver lining, the main one really, is real-life practice. Writing is and remains an ‘organizational technology’ for thinking (Eddy, 2023). By writing notes, and experimenting with doing it better (whatever better means), people are gradually improving their skills at writing and thinking productively and meaningfully.

Until the hype settles down, AI is revolutionising our understanding of the significance of literacy, but the need to organise our thoughts effectively will probably increase, not decrease. Making notes, whatever the ‘method’ or ‘approach’, will continue to have a place in the intellectual toolkit.

That’s my view and I’m sticking to it until you convince me otherwise. I’ve found the Zettelkasten approach to making notes very helpful and I know others have too.

Now read:

Don’t let your note-making system infect you with Archive Fever.

What to do when you’ve made some notes.

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters. It’s a short and accessible introduction to the concept, available now.

And if you liked this article, why not subscribe to the weekly Writing Slowly email digest?

References

Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech genres and other late essays. University of Texas Press.

Bennett, T. (2005), ‘Civic Laboratories: Museums, Cultural Objecthood and the Governance of the Social’, Cultural Studies, 19(5): 521-547. Preprint PDF

Cetina, Karin Knorr (2001). Objectual practice. Ch.12 in The practice turn in contemporary theory. Ed. Theodore R. Schatzki. London: Routledge, 17-18. P. 182

Eddy, Matthew (2023). Media & the Mind : Art, Science, and Notebooks as Paper Machines, 1700-1830. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Hajer, Maarten A. (2009). Authoritative Governance: Policy-Making in the Age of Mediatization. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Hajer, Maartin (2024). Teaching discourse and dramaturgy. Ch. 20 in St. Denny, Emily, and Philippe Zittoun, eds. Handbook of Teaching Public Policy. Cheltenham, UK ; Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Rheinberger, Hans-Jörg (1997). Toward a history of epistemic things: Synthesising proteins in the test tube. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

-

Rheinberger argues that scientific research is driven by the investigation of “epistemic things”—entities or phenomena that are not yet fully known or understood. These “things” emerge within “experimental systems,” which are the material and conceptual arrangements of research. Rheinberger claims these systems don’t just reveal pre-existing objects but actively shape and bring forth these epistemic things through the ongoing process of experimentation. In this way the unknown plays a key role in scientific discovery. ↩︎

-

“A discourse coalition is a set of actors that, via their activities in particular practices, shares and reproduces a particular construction of reality (cf. Hajer 2009). Note that actors within a particular discourse coalition do not necessarily agree with each other on matters of substance; yet they share a language to express their concerns and fight their fights. Hence, they will also search for solutions within the confines of the reality that that particular discourse allows one to express.” (Hajer 2004:300). ↩︎