“Sometimes it’s just nice to know there are other people out there quietly thinking things through.” - writingslowly.com

📷Photo challenge day 30: solitude.

💬"I am the Cat who walks by himself, and all places are alike to me." - Rudyard Kipling.

And there’s more solitude.

#mbjune

Don't let your note-making system infect you with Archive Fever

The Zettelkasten note-taking system offers a structured approach to organizing thoughts but might induce “archive fever,” which may lead to an obsession with preservation over actual writing. Here’s how to protect yourself.

📷 Photo challenge day 26: bridge.

I’ve used this as a metaphor for writing, but it’s also a real bridge, of which #Sydney has many more than the famous one across the harbour. The image shows the causeway to Bare Island, at the mouth of Kamay, Botany Bay.

#mbjune

📷 Photo challenge day 29: winding.

It’s well worth taking a look inside White Bay Power Station in #Sydney - as previously seen on day 7 and day 5. Oh, and day 23 last year.

See the whole #mbjune photogrid.

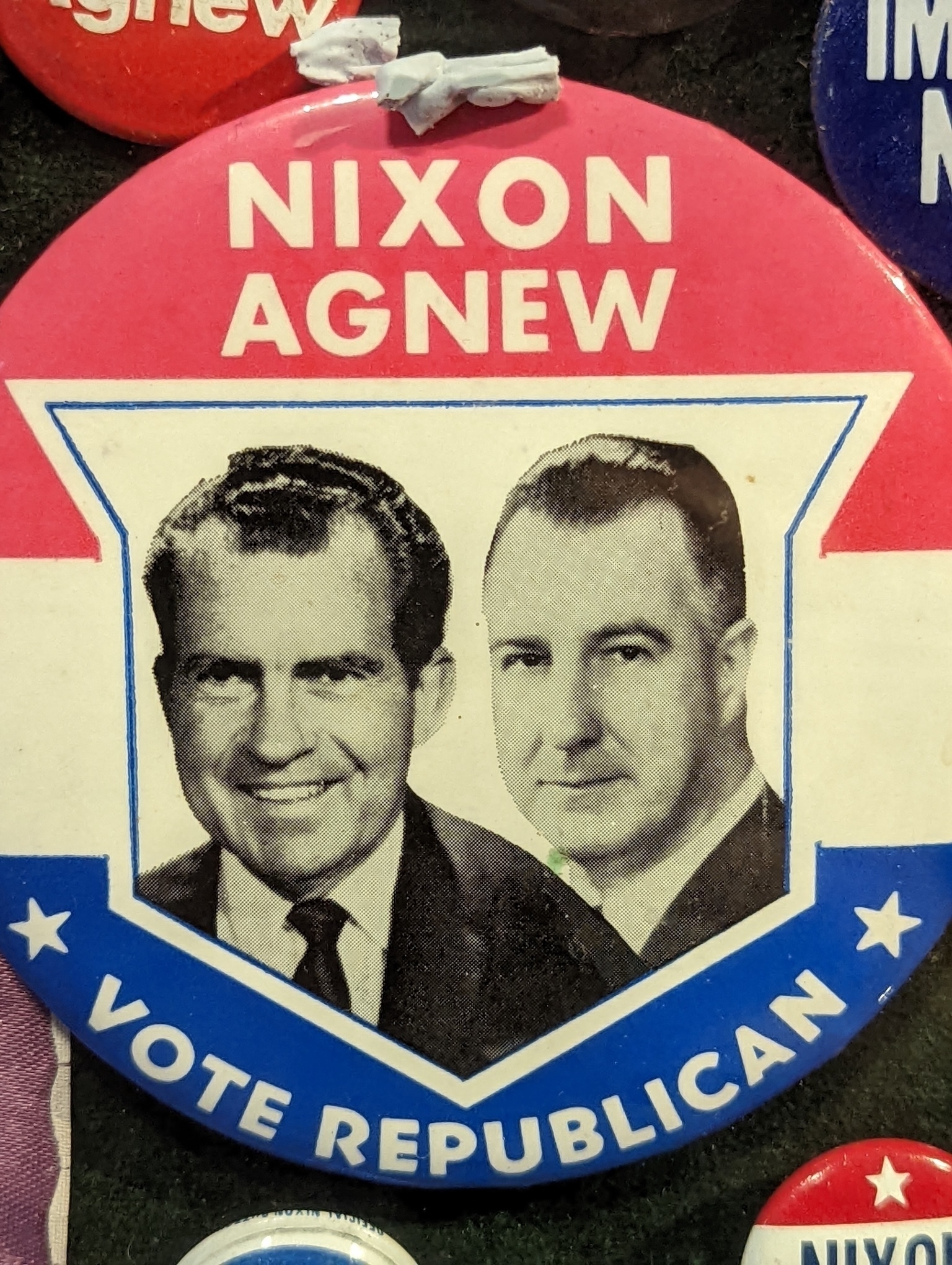

📷 Photo challenge day 28: ephemeral. A reminder that our leaders don’t last forever, or even for as long as they’d like to. I spotted this election button on the very last day the Leura toy museum was open, in the Blue Mountains, just West of #Sydney.

#mbjune

📷 Photo challenge day 27: collective. Rainbow lorikeets are among the most commonly seen #birds in #Sydney.

#mbjune

💬"In these unprecedented times, it’s more important than ever to find better ways to care for and love our neighbors," - Mon Rovîa.

See also: Who says to care is to disobey?

📷 Photo challenge day 25: decay.

My worm farm is amazing! By turning waste into compost these little wrigglers perfom a kind of magic.

It’s also a metaphor for my writing process. I don’t worry if the input is rotten. The output will be quite different.

See also: No writing is wasted

📷 Photo challenge day 24: bloom.

The bougainvillea does get a bit unruly, but it’s probably worth it. #mbjune

📷 Photo challenge day 23: fracture.

A crack in reality at the Edogawa Japanese Garden, north of #Sydney

#mbjune

Don’t throw away your old notes

Don’t throw out your old notes, even if you feel overwhelmed by them. Here are some helpful ideas on what to do instead.

💬 Back in 2018 I said “the next Web will be fit for humans”.

And how did that little prediction go? Well, I’ve updated my original post with some reflections.

📷 Photo challenge day 22: hometown.

The view from Yerroulbine (Balls Head) on our mid-winter walk in #Sydney yesterday. From this angle Me-mel (Goat Island) seems impossibly close to the CBD.

#mbjune

How Walter Breuggemann shaped me

At its best, a family can be ‘a communal network of memory and hope in which individual members may locate themselves and discern their identities’

📷 Photo challenge day 20: gather.

Six seagulls gather on a sandstone rock at La Perouse, #Sydney.

#mbjune

What to do when you've made some notes: Start writing

The next step after taking notes is to create a finished piece of writing, acknowledging that the first draft may be disorganized but serves as a foundation for improvement.

📷 Photo challenge day 19: equal.

💬 “I exist in a fractally connected, self-organized universe where everything relates dynamically to everything else” - Jeremy Lent, The Web of Meaning.

Yes, we all do.

#mbjune #zettelkasten

Bob Doto is the author of ‘A System for Writing’.

From reading to note-making to finished draft, his approach connects it all.

I watched his discussion with historian Dan Allosso and took notes so you don’t have to.

#WritingCommunity #NoteTaking #PKM #Zettelkasten #BookWriting #SlowWriting