📷 Day 12: magic

📷 Day 11: sky

📷 Day 10: train

📷 Day 9: crispy

Finished reading: To Be Taught, If Fortunate by Becky Chambers 📚My backlog of sci-fi reading is getting a little smaller.

Finished reading: A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers 📚I seem to be getting through the pile of sci-fi books that never shrinks but only grows.

📷 Day 8: prevention.

📷 Day 7: I’ve posted this photo before but it’s definitely my idea of wellbeing.

📷 day 6: windy

📷 Day 5: serene

Remembering 2 Tone records.1 (I once met Jerry Dammers’ dad. He was an extremely proud father).

-

HT Alan Ralph. ↩︎

📷 Micro.blog photo challenge April 2024. Day 4: foliage

#mbapr

💬“Peace of the sort that brings wholeness, harmony, and health to our lives only happens when chaos, confusion, and conflict are included and transcended.”

- Harrison Owen, creator of Open Space Technology.

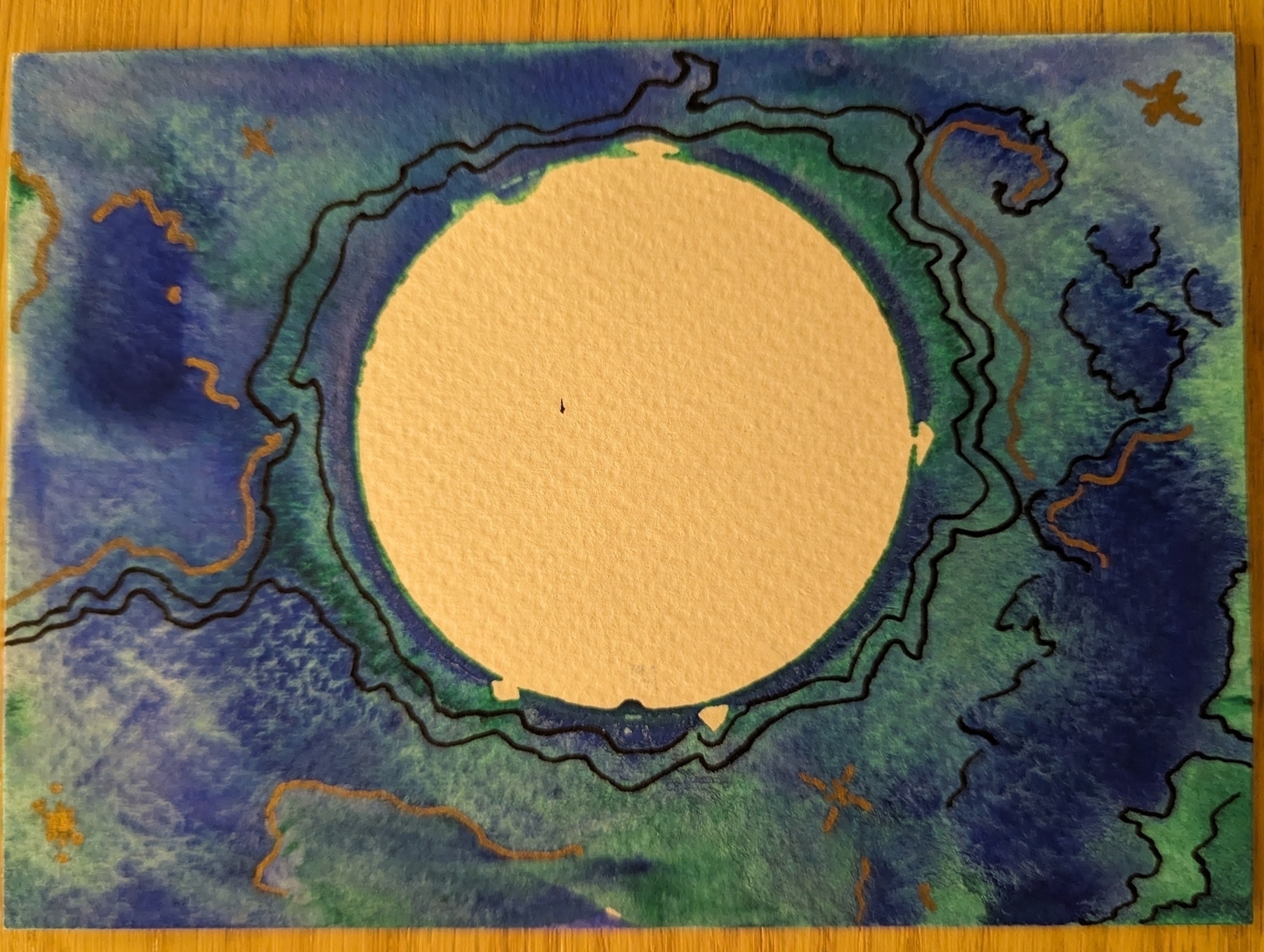

Micro.blog photo challenge April 2024. Day 3: Card. My daughter made this card for my birthday, to go with a themed collection of sci-fi novels.

#mbapr

📷 Micro.blog photo challenge April 2024. Day 2: Flowers. This extraordinary bunch came our way. What a beautiful gift!

#mbapr

📷Micro.blog photo challenge April 2024. Day 1: toy

How to set your own agenda

Harrison Owen, who died in March 2024, invented one of the most hopeful approaches to group facilitation I’ve ever come across. He called it ‘Open Space Technology’ (OST), but it was far from hi-tech. In fact, the main ‘technology’ was simply in how people in a group setting can interact fruitfully with one another, even when they really don’t agree.

“Peace of the sort that brings wholeness, harmony, and health to our lives only happens when chaos, confusion, and conflict are included and transcended.”

- Harrison Owen, creator of Open Space Technology.

I first came across Open Space as a means of organising workshops in highly contested political spaces.

In the UK during the 1980s and early 1990s progressive social activity was constantly undermined by Trotskyites (or whatever they were) striving to co-opt social movements for their own ends. There was always a risk that as soon as you set up a committee of any kind, they’d get themselves voted onto it and turn it into a front for the true workers revolutionary communist workers party, or some such combination of those terms.

But what were the alternatives? The Labour Party had been hammered with this problem, and had settled on a full-blown witch hunt against anyone affiliated with the Militant Tendency, which like a monstrous baby cuckoo had nearly pushed them out of their own nest. We’d witnessed how the so-called cure was nearly as bad as the disease.

I think it was about 1992 when we organised our own small Open Space event. Of course, the entryists turned up, but the Law of Two Feet really stumped them. When they realised anyone could set the agenda they were delighted. This must have seemed much easier than having to take over by stealth! But when the discussions began they were confounded by the fact that, equally, anyone could just walk away and find something more important to them. To everyone except the entryists, the experience was delightful.

Image by Chris Kinkel from Pixabay

Of course, OST didn’t change the whole world, and it’s not useful for every meeting. But it was formative for me personally, because I could see how people could come together to identify, commit to and begin to solve their own problems, without waiting for someone else to do it for them.

Open Space Technology has also left a strong mark on facilitation generally. Unconferences, World Café, Bar Camp, the Art of Hosting, design sprints, and many other approaches owe a great deal to Harrison Owen’s pioneering determination to trust people to pursue their own agendas.

Vale Harrison Owen.

More:

Working in Open Space: A Guided Tour

Finished reading: A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers 📚

I found this almost too whimsical yet strangely moving. A bit like my life then.

When it comes to writing notes, how much mess is just enough?

Oliver Burkeman, author of Four Thousand Weeks, likes to keep his notes messy1:

“‘Messiness’, in this context at least, is just the state of not being so hubristic as to imagine that you know, in advance, precisely what’s required in order to do or to create something worthwhile. Which, of course, nobody does.” - The life-changing magic of not tidying up

I really appreciate the benefits of serendipity, but I also need some structure, which is why I’m happy with making atomic notes, densely linked. You might call it a Zettelkasten. Burkeman says he tried a Zettelkasten approach to his notes, but found it too organised.

That’s not at all how I’ve experienced it.

The image that for me best sums up this process of making short notes to create longer pieces of writing is that of my little worm farm. All sorts of scraps get dumped in at the top. And mostly unseen, the worms turn everything into nourishing compost.

It’s almost magical.

So instead of being obsessive, I just have a few simple rules that I mostly stick to.

- Plain text (Markdown) notes.

- Each note is a single idea with a unique ID.

- Each note deserves a clear title.

- Notes link meaningfully to other notes.

And while this little system might not result in much tidiness, it’s still really neat.

Really looking forward to forward to photoblogging in April. It’s simple: just post a photo every day for a month. But I’ve been surprised to find how much I like it. Thanks to @jean, who has some thoughts on whether or not it’s a ’challenge’.