books

- A video interview with the author.

- A summary of the argument, adapted from the introduction: The Surprising New Significance of Shu Ha Ri in Postwar Karatedo.

- A 1983 BBC documentary about Okinawan karate: The Way of the Warrior: Karate, the Way of the Empty Hand. This is extraordinary and a real classic! (mentioned in a footnote on p.97).

-

but don’t take my word for it, what do I know? Read the book and the close reading archive. ↩︎

Leonard Koren on Life as an Aesthetic Experience

I’ve never been much of a bathing person. Perhaps that’s due to unpleasantly lingering memories of luke warm water in freezing cold bathrooms in the UK when I was a child. The bath was fine enough, but getting out would be a real test. Even bathing, as an adult, in natural hot springs on Orcas Island in the US Pacific Northwest didn’t really do it for me. That was a little ‘rustic’, and not in a good way.

True, swimming here in Sydney where I live is fabulous, especially in the Summer, when the cool refreshment of the ocean waves is totally restorative. But bathing? Not so much. Until a few months ago, that is, when I visited Japan.

I hadn’t really understood the national Japanese obsession with bathing, but once I realised there are natural hot water sources all over the place in this volcanic archipelago, and how culturally central they are, and how refined the Japanese have made the whole bathing experience, I was completely hooked. In fact, returning to Australia, it feels strangely hard to live without it. Happily, a new spa and sauna has just opened up in our little neighbourhood, where my partner is already enjoying her season ticket. Come the Autumn, or even sooner, I’ll surely be joining her.

Which brings me to Leonard Koren, the august founder in the 1970s of ‘Gourmet Bathing’ magazine. He tells that story in a podcast interview. What particularly drew me to the interview though, was his account of how he came to write what he’s best known for — his cult book Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets and Philosophers. This book, published in 1994, has pretty much inspired not one but two cottage industries: one that centres on the concept of wabi-sabi, which now counts literally dozens of books exploring every possible angle of the term; and a second cottage industry that revolves around the exploration of Japanese concepts other than wabi-sabi, of which there are also now dozens. Who among us has not now heard of ikigai (finding your purpose), kaizen (continuous improvement), mono no aware (beauty in impermanance), shoshin (beginner’s mind) and so on and so forth?

Time Sensitive Podcast S11 E128 - 2 April 2025.Leonard Koren on Life as an Aesthetic Experience

I learned a few things from this podcast.

First, I learned that Leonard Koren had always intended to self-publish his book.

“When I made the first book," he said, “I thought it would be extremely niche… I realized that I would have to publish it myself.”

Second, I was happy to hear him fully owning the little secret of Wabi-Sabi, that there’s no such thing.

“Let me just be very clear: In Japanese there is no term wabi-sabi, OK? There’s an old word, ‘wabi’ and an old word ‘sabi’. If you look in the Japanese dictionary you won’t find wabi-sabi, period.”

Third, I was very taken with Koren’s description of his creative life:

”My life is essentially an aesthetic experience. Everything I know, everything I take in, every idea I have, comes to me through my senses. And then it’s processed.”

Well, Koren’s book is, quite clearly, the direct inspiration for my own, Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters.

They’re both short, just 100 pages.

They’re both direct, covering one concept and one concept only.

They’re both Artist’s books, including photography (mine has 20 photographs of Japanese gardens, which I took myself).

They’re both originally self-published, to enable a singular, perhaps eccentric vision to find full expression.

They’re both the first book on a Japanese concept that no one in Japan, or anywhere else, has written yet, at least not a long-form treatment.

They’re both at the leading edge of an emerging trend.

Wait! What? What emerging trend is this? Well, I waited 15 years for someone better qualified than me to write about the concept of Shu Ha Ri. No one did. At least, no one else wrote a clear, well-referenced, accessible introduction. Eventually I relented, wrote the book I wished already existed, and put it out there for readers to make their own judgement. But what do you know? Very shortly after I published my own introduction to the concept, another appeared, written by the partnership of Hector Garcia and Nobuo Suzuki. It’s in Spanish only for now, but the English version is published by Tuttle in August 2026, so perhaps soon there’ll be a Shu Ha Ri cottage industry. You heard it here first.

On my recent visit to Japan I walked past a gift shop in the small city of Matsumoto called ‘WabiXSabi’ (yes, in English), and it turns out there’s a whole chain of these stores across Japan. So maybe one day in the future someone will open a Shu Ha Ri shop, selling who-knows-what. Maybe it’ll be a footwear store. You heard that here first too.

But here’s word of warning to anyone thinking of trying this: Best not be selling anything fragile. Translated literally, Shu Ha Ri means ‘hold, break, leave’.

—

As you might have gathered, I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now.

And if you found this article interesting you might like to sign up to the Writing Slowly weekly email digest. You’ll receive all the week’s posts in that handy email format you know and love.

📚Tsundoku emergency temporarily averted.

Some books I read before visiting Japan.

#reading #Japantravel #shuhari

After launching my book on the Japanese concept of Shu Ha Ri I’m visiting Japan itself soon to research another concept that’s become a minor obsession.

I’m particularly interested in traditional Japanese gardens and in traditional crafts, so where should go? If you know Japan, what tips have you got to share?

#Japan #shuhari #Japantravel #Japanesegardens

Mastering Any Skill, the Japanese Way

📚 A review of Analysis of Shu Ha Ri in Karate-Do: When a Martial Art Becomes a Fine Art by Hermann Bayer, Ph.D.

Most people believe that mastery of a skill comes from practicing harder and longer. ‘10,000 hours of deliberate practice’ has achieved a level of imperative unwarranted by the actual evidence (Epstein, 2021). Yet countless learners, whether in business, the arts, or sport, hit a plateau they can’t break through. The problem isn’t effort. It’s that they’re missing a hidden progression that separates the true experts from the merely experienced.

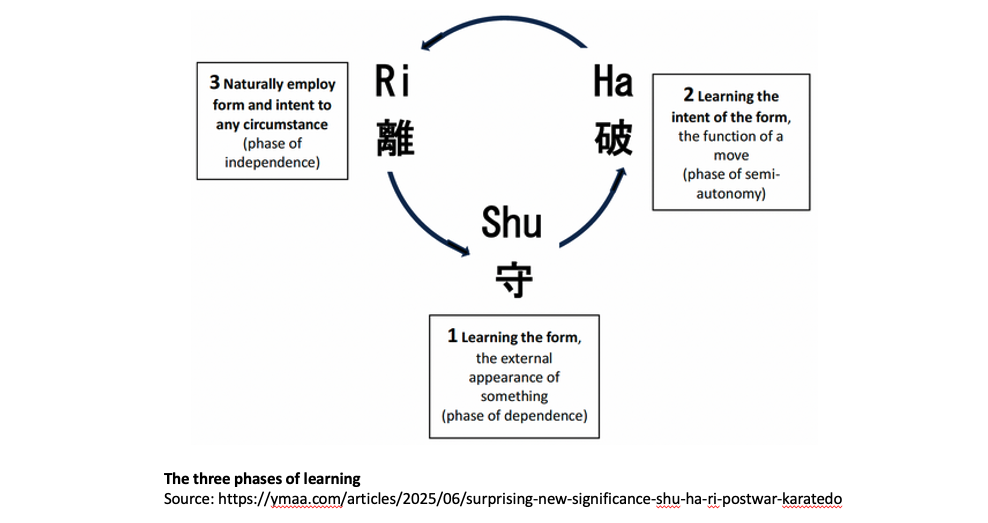

For centuries, Japanese masters have understood this journey. It has three distinct phases, Shu, Ha, Ri, and each demands a different mindset and approach. Skip one, and your growth stalls. Get them right, and you move beyond imitation into competence and ultimately mastery. Unlike many Western theories of learning, it’s not a linear set of stages to be climbed like the rungs of a ladder: instead it’s a cycle, a spiral of increasing competence where the earliest phase is never forgotten.

Hermann Bayer’s Analysis of Shu Ha Ri in Karate-Do is one of the clearest and most extensive explanations of this progression I’ve encountered. While his examples come from Okinawan karate, his real subject is the universal process of moving from novice to master, potentially in any discipline.

Bayer brings to his writing both deep scholarship and decades of martial arts expertise. This shows, but the book remains reasonably accessible for general readers. He unpacks philosophical ideas without jargon, showing exactly how they play out in practice. One of his most important clarifications is effectively a major theme of the book: Shu Ha Ri is not an Okinawan tradition. Despite its frequent modern association with karate, Bayer shows that the concept comes from Japanese fine arts, especially from the tea ceremony, and only entered karate after karate’s fairly recent introduction to mainland Japan, in 1922. This detail is more than just historical trivia; it changes how you see the concept. Shu Ha Ri is not tied to a single fighting style, and certainly not to karate. It’s potentially a transferable blueprint for mastering any complex skill.

Although Shu Ha Ri has wide applicability and has been adopted in many different disciplines, Bayer does focus heavily on karate, and on its Okinawan origins. This is the author’s specialist field. He is, after all the author of the two-volume Analysis of Genuine Karate, which explores Okinawa as the cradle of true karate. So readers curious about Shu Ha Ri, but with limited interest in karate and Okinawan history may wish for more examples from other disciplines. But the underlying framework is so universal that the author’s examples still work. You don’t need to know a kata from a kumite to apply what you learn.

If you are a practitioner of Karate, I suspect after reading this book you’ll never see it in quite the same way. But what makes the concept of Shu Ha Ri valuable beyond martial arts is its potential application to any field where performance and creativity matter. For instance, writers might see how to move from imitating their influences to developing a unique voice. Leaders might understand when to enforce process and when to encourage innovation. Artists, athletes, and entrepreneurs might recognise the moment to step beyond rules without losing their foundation.

If you care about personal growth and continuous improvement, or want a proven roadmap to mastery, this book will give you both the theory and the practical insight to get there. By the time you finish it, you won’t just understand Shu Ha Ri, you’ll be inspired to integrate this learning philosophy into your own life. And in case you were tempted, you will never again confuse Shu Ha Ri with the historical traditions of Okinawan karate.

Details

Analysis of Shu Ha Ri in Karate-Do: When a Martial Art Becomes a Fine Art by Hermann Bayer, Ph.D. (June 2025, ISBN: 9781594399954)

Purchase directly from the publisher, YMAA.

Resources

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters. It’s a short and accessible introduction to the concept, available now.

And if you enjoyed this review, you may like to subscribe to the weekly Writing Slowly email digest.

The cat is characteristically ecstatic to see that the proofs of the new book have arrived. Not long now before it’s published!

Update: I did it. Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters is now available. I hope you enjoy it!

#amwriting #booklaunch #comingsoon #nonfiction

As Alan Jacobs says, reading more books and reading books more - they’re not the same thing.

I designed a book in three and a half hours

A while ago, well, quite a long while ago, I designed a book in three and a half hours. Fun, yes, but it wasn’t very publishable.

Now, years later, I’ve finally got round to updating and redesigning the whole thing.

Yes, I’m still writing slowly but I’m excited to say it will soon be available for sale - so watch this space for more information.

Worth repeating and re-repeating:

“the evidence shows that regularising migration is a positive-sum game, in economic, social and security terms.”

A definitive study of a hotly debated phenomenon: migration into Europe and America, its socioeconomic impacts, and the eternal policy efforts to stop the inevitable.

#migration

A search for meaning in the palace of lost memories: Thoughts on Piranesi, a novel by Susanna Clarke

Susanna Clarke’s novel Piranesi has got me thinking about memory, identity, the fallibility of writing, and the paradox that intrinsic value might be created rather than found

Finished reading: This Is Happiness by Niall Williams 📚

A shaggy dog story in the best possible sense. I re-read several passages to try to work out how the author achieved his almost magical prose. Friends who read it said they felt not much happened. I felt not much happened, miraculously.

Daniel Wisser’s notecards as art and archive

Daniel Wisser’s exhibition in Vienna features 60 index cards with sketches of stories displayed in a note box (Zettelkasten).

Have you ever read a book by mistake?

Confession time: a mistaken identity led to the discovery of Cynthia Ozick’s novel The Messiah of Stockholm, which I enjoyed despite initially confusing it with a work by Ruth Ozeki.

Well the book arrived this morning. Now I really am publishing slowly!

Publishing slowly

I’m writing so slowly that you might be wondering if I’m ever going to get anything published.

Well wonder no more. I’m happy to say extracts of my memoir, ‘The Green Island Notebook’ are published in the anthology Destinations & Detours: New Australian Writing.

Published by Detour Editions, the collection launches here in Sydney on Sunday 2nd March 2025, and if you happen to be in the vicinity, I’d be delighted to meet you in person.

Book Launch 2pm, Sunday 2nd March, at Randwick Literary Institute, 60 Clovelly Road, Randwick NSW

Watch out too for news of how you can get your hands on a copy, wherever in the world you find yourself.

And this isn’t the only news on the publishing front. I’ll be sharing details of some further publishing adventures very soon.

But don’t worry, whatever happens, I’ll still be writing slowly.

Update: Oh look, I wrote another book: Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters.

Randwick Literary Institute, the venue for our book launch, celebrates its 100th anniversary in 2025. Here it is in 1957, and it hasn’t changed much since then:

Subscribe to the Writing Slowly weekly digest (unsubscribe any time):

To care is to disobey

The book Pirate Care discusses how the act of caring for others has been criminalized, and it advocates for a grassroots political practice of solidarity against oppressive legal measures.

Read better, read closer

For anyone seeking clues on better techniques for reading, Scott Newstok, author of How to Think Like Shakespeare, has created a marvelous resource: a close reading archive. Here is where all your close reading questions will be answered, including, what is it? how do you do it? what have people done with it? and does it have a future in a digital age?

Close reading is one of those two-word phrases that seem to take on a life of their own. Anyone connected to the humanities has probably heard of it, but it’s not necessarily well understood. Is it finished? Apparently not. Not at all.

Professor Newstok’s close reading archive is an openly available companion to John Guillory’s cultural history, On Close Reading, published January 2025.

Newstok is also editor of a book on Montaigne’s view of teaching, which is how I discovered Gustave Flaubert’s endorsement of what might perhaps be seen as a kind of close reading avant la lettre1:

“Read Montaigne, read him slowly, carefully! He will calm you . . . Read him from one end to the other, and, when you have finished, try again . . . But do not read, as children read, for fun, or as the ambitious read, to instruct you. No. Read to live.”

Now consider: three ways to make notes while reading.

For even more, please subscribe.

Notemaking helps you remember - and helps you forget

Do we really need to remember everything?

This is the question posed by Lewis Hyde’s memorable book, A Primer for Forgetting: Getting Past the Past 📚

He says:

“Every act of memory is an act of forgetting. The tree of memory set its roots in blood. To secure an ideal, surround it with a moat of forgetfulness. To study the self is to forget the self. In forgetting lies the liquefaction of time. The Furies bloat the present with the undigested past. “Memory and oblivion, we call that imagination.” We dream in order to forget.” ― Lewis Hyde, A Primer for Forgetting: Getting Past the Past

Forgetting is the essence of what makes us human

The subtitle of Joshua Foer’s book, Moonwalking with Einstein, promotes the art and science of ‘remembering everything’. Yet Foer accepts that forgetting is an essential aspect of memory. He quotes the Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges:

“It is forgetting, not remembering, that is the essence of what makes us human. To make sense of the world, we must filter it. “To think,” Borges writes, “is to forget.” – Joshua Foer, Moonwalking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything

A System for Writing by Bob Doto

“The note you just took has yet to realize its potential.” - Bob Doto.

Another ‘Zettelkasten primer’ won’t be needed for some time, since this one is direct, concise, thorough and strongly practical. A System for Writing by Bob Doto is out!

💻 Ebook

A System for Writing by Bob Doto

“The note you just took has yet to realize its potential.” - Bob Doto

Another ‘Zettelkasten primer’ won’t be needed for some time, since this one is direct, concise, thorough and strongly practical.

📚A System for Writing by Bob Doto is out!