Jules Verne could have told us AI is not a real person

A castle of mysterious voices

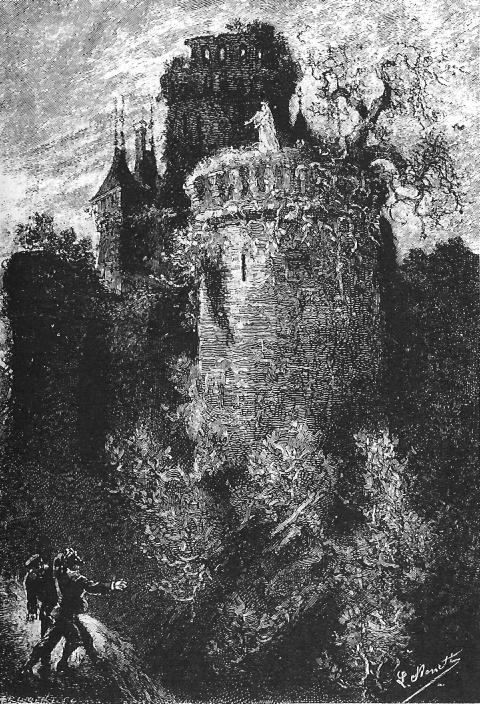

In one of French writer Jules Verne’s many sensational novels, The Carpathian Castle, the hero, Count Franz de Telek, investigates a creepy Transylvanian castle. The castle is rumoured to be haunted by the ghost of his former love, the Italian opera diva, La Stilla. Rumours of sightings suggest that sensationally, La Stilla has come back to life!

“If La Stilla were dead, how came it that Franz could hear her voice in the saloon of the inn, see her on the bastion, and listen to her song when he was in the crypt? And how could he have found her alive in the donjon?”

After much gothic prose, it turns out that [Spoiler:] the supposed ghost is nothing more than a photographic wall projection and a ‘high quality’ phonograph recording of the singer’s voice. The re-staging of La Stilla’s performance has been set up for the castle’s owner, Baron Rodolphe de Gortz, who had also loved La Stilla when she was alive.

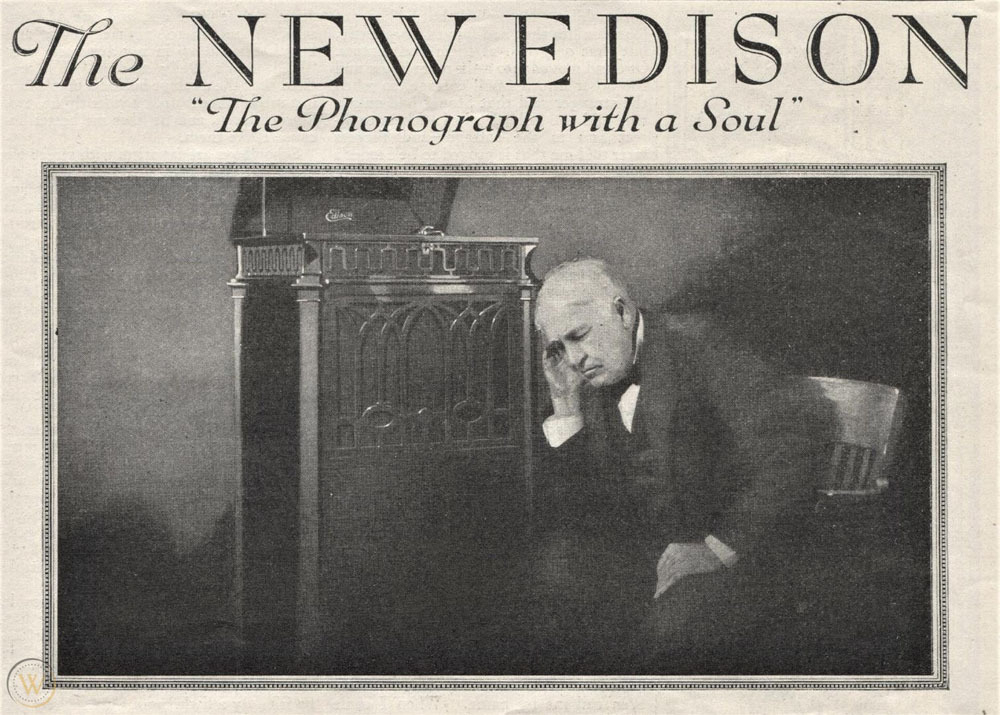

In 1892 when the novel was published, these were still new inventions, so readers would have found the happenings at the castle truly mysterious, and the ending not at all corny. Verne probably first experienced a demonstration of an Edison phonograph 14 years previously, at the 1878 Paris World’s Fair, and it appeared shortly after in his 1879 novel, The Tribulations of a Chinaman.

In fact, the story is more science fiction than Gothic horror (‘This story is not fantastic, it is merely romantic", states the author at the start). New technology presents the convincing appearance of life, which fools all observers - until the trick is finally revealed. And even then, there are some who prefer to believe in the supernatural explanation, despite the evidence.

La Stilla Syndrome

You can probably see where this is going.

With the rise of large language models (LLMs), we are once more suffering from La Stilla Syndrome. That’s my Jules Verne-inspired name for the condition in which we keep allowing our technology to fool us into thinking it has finally come alive.

But it’s not the technology itself that’s tricking us, any more than La Stilla the Italian diva had any hand in her audiovisual reconstruction. She was well and truly dead. It was the Count’s sidekick Orfanik who staged the counterfeit, and he alone was to blame for the conceit.

Now, with applications such as Claude, ChatGPT and Gemini (formerly Bard), Microsoft and Google are tricking us into seeing a living diva where there is none, and amazingly, even after 120 years of familiarity with this kind of tall tale, we still fall for it.

We’ve learned nothing from Jules Verne. We’re still suffering from La Stilla Syndrome.

You might be thinking…

You might be thinking: “Well it’s too obvious, I wouldn’t fall for a crude trick like that”. But the point of Jules Verne’s novel is that even after the mechanism has been revealed, many of the characters persist in believing there was a real ghost - and nothing will dissuade them that the mechanised singer wasn’t a really present human, back from the dead.

And then you might be thinking, “The phonograph was just a crude recording machine. It was way back in the nineteenth century. That’s completely different from the real technological revolution that AI represents right now”.

If so, you should be aware that the phonograph was a real technological revolution. Thomas Edison wrote an improbably long list of all its possible uses. Every one of them came to pass. The author of a Scribner’s article in 1878, “A Night with Edison’, reported breathlessly:

“The invention has a moral side, a stirring, optimistic inspiration. ‘If this can be done,’ we ask, ‘what is there that cannot be?'” (p.88)

False people should be banned

Given the extent to which people almost want to be fooled, philosopher Daniel Dennett argues that ‘false people’ should be banned. I’m not going to argue with this. At the very least, corporations should immediately stop using the first person pronoun, “I”, in the interface between their chatbots and us, the gullible humans.

No more of Siri ‘saying’:

“I’m a virtual assistant, not an actual person, but you can still talk to me.”

No more obfuscation like this response when I asked Google, “Are you an actual person?”

“I’m really personable. Does that count?”

No, it doesn’t count.

Today, for the first time in history, thanks to artificial intelligence, it is possible for anybody to make counterfeit people who can pass for real in many of the new digital environments we have created. These counterfeit people are the most dangerous artifacts in human history, capable of destroying not just economies but human freedom itself. Before it’s too late (it may well be too late already) we must outlaw both the creation of counterfeit people and the “passing along” of counterfeit people.

Advertisers once claimed the phonograph was so life-like it actually had a soul.

It didn’t then. And AI still doesn’t now.

But if now we can see through the advertising gimmick of a century ago, why are we letting ourselves be fooled by the most recent advertising trick? Is there any cure for La Stilla Syndrome? Or will time, yet again, be the only healer?

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri: The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, out now.

See also:

More than ever, embracing your humanity is the way forward.

Despite AI, the Internet is still personal

Since AI can easily write everything correctly with perfect spelling and punctuation, one way to show you’re human is to do the opposite.

The single best way to supercharge your workflow with AI writingslowly.com

Phonographia.com has a long list of ‘phonoliterature’ - books in which a phonograph appears at least once. In fact, Verne’s tale is almost repeated in Arthur Conan Doyle’s much shorter 1899 version, ‘The Story of the Japanned Box’. People were obsessed with this revolutionary technology.

Very happy the videos are already available from micro.camp. It was frustrating to be (not) watching from a distant time-zone, but I’m looking forward to catching up!

I read the top ten Zettelkasten posts on Hacker News so you can do something more wholesome with your day

I really did read a lot of geeky Zettelkasten posts and now I’m going to share them with you

Every so often someone on Hacker News mentions Zettelkasten, a method of making longer work from simple, connected notes. An interesting conversation usually follows. Several of these posts have reached the front page of the Hacker News site, making their authors ‘HN famous’, which is the geek’s version of blowing up on TikTok. The top Zettelkasten post there has around 300 comments, while the 10th has 31.

It’s worth staying a little sceptical about whether visibility on Hacker News is a good proxy for competence. But the comments are usually interesting and often helpful. So here’s a countdown of the top Zettelkasten posts, from 10 to 1. And here, top simply means ‘most commented upon’. For your reference, I’ve noted whether each article is introductory/basic, intermediate/involved, or advanced/complex.

And I’d be interested to know what your favourite Zettelkasten article or resource is - there are a lot to choose from. Or else feel free to tell me exactly why you think this is all a daft waste of time.

So now…

The Zettelkasten article top ten countdown

10. Zettelkasten, linking your thinking, and Nick Milo’s search for ground

Bob Doto, presents a constructive comparison of two different approaches to note-making. The Zettelkasten method, and Nick Milo’s ‘Linking Your Thinking’ (LYT) may appear similar, but as this article points out, they’re really quite different:

“The things that differentiate zettelkasten from LYT are the very things that make each system truly work.”

Bob has some additional articles about the Zettelkasten approach, which are highly recommend.

Complex

Principles

Comparison

9. Org-roam-UI – graphical front end for exploring your org-roam Zettelkasten

Org-Roam is a plain text knowledge management system based on Emacs Org-mode. This post provides an add-on visual interface that shows a map of your notes, similar to other tools such as Roam, Obsidian and Logseq. The tool is “a frontend for exploring and interacting with your org-roam notes.” If you use Org-mode and think you might need this, read on.

Complex

Tools

Github Repo

8. The Zettelkasten Method (2019)

Abram Demski of lesswrong.com goes to town on explaining the evolution of his paper-based Zettelkasten system. He uses 3x5 inch index cards, but he also tried Workflowy and has nice things to say about it. There’s a follow-up at the end, in which the author says he now uses notebooks, but still finds the Zettelkasten referencing system very useful. Along the way he offers one of my favourite principles: “small pieces of paper are just modular large pieces of paper”. This particular article also one of Abram’s top posts on lesswrong.com

Complex

Manual

Principles

Tools

Examples

(Yes, this article covers a lot)

7. My Second Brain – Zettelkasten

Web developer Scott Spence writes about the tools he has been using for notetaking: GitHub, Notion, RoamResearch, Obsidian, Foam. There’s a helpful warning at the top of the article that since it’s three years old the technical details may be out of date. This post is for lovers of digital tools!

Involved

Tools

6. Luhmann’s Zettelkasten

An article from a small German software company about Niklas Luhmann and the structure of his notes. Warning: the description here of how Luhmann connected notes through consecutive numbering (Folgezettel) seems a little simplistic. And TBH I’m not sure how useful this article really is, but the authors do seem to have succeeded with the HN popularity contest.

Basic

Article

5. Introduction to the Zettelkasten Method

A very full introduction to the Zettelkasten method, by Sascha Fast of zettelkasten.de. It’s a great introduction, which also goes into useful depth. If you’ve already been building your Zettelkasten for a while, it’s worth coming back to this to see what you can pick up now you’ve got a real example to play with. These guys also have an app (the Archive) and a great forum, but if you’re reading this you probably already know that.

Involved

Manual

Examples

4. Zettelkästen?

Brian Kam (of Interintellect) writes a simple summary of the Zettelkasten approach, with a follow-up post two years later, by which time he was no longer a beginner since he’d written (drum roll…) 6,837 notes. He implements his Zettelkasten with a Git-based wiki.

Basic

Principles

3. A tour to my Zettelkasten note clusters

Involved

Example

Tech writer Mingyang Li describes his Zettelkasten categories in Obsidian. There are categories like ‘Journal’, ‘chat with people’ and ‘distinguishing-between’. It’s quite useful to see how one person benefits from specific clusters of notes.

2. Zettelkasten note-taking in 10 minutes

Basic

How-to

GitLab software engineer Tomas Vik runs through the slip-box method, based on Sönke Ahrens’s book, How to Take Smart Notes. He recommends creating individual plain text (markdown) files and gives clear examples of how this is structured. He used Zettlr as his markdown-enabled text editor of choice, but mentions alternative apps that do similar things. As a bonus, there’s a follow-up post a year later, in which the author describes how his process has changed (not much) and why he now uses Logseq instead of Zettlr.

1. Stop Taking Regular Notes; Use a Zettelkasten Instead

Basic

How-to

Amazon data scientist Eugene Yan wins the HN Zettelkasten popularity prize with his post on how he implements the system in Roam. Well, it has attracted the most comments anyway. It’s a useful introduction, and commenters mention other apps such as TiddlyWiki, Obsidian and Workflowy. The author seems to have moved on, and started using Obsidian in 2023.

Reflections

Well done If you’ve read this far you are clearly my kind of person. Though you’ve probably noticed that these aren’t necessarily the very best articles about the Zettelkasten method. In any case, everyone differs on what that would even mean. But if you want to gain an understanding of this particular approach to note-making and writing, most of these articles are well worth reading. And if this was all you had available you’d certainly be able to make a good start.

I was interested to discover that quite a few technically-competent people are interested in the Zettelkasten, and are even using one, and was mildly amused to see how keen some seem to be on their many and various digital tools.

I found the follow-up posts, where they existed, the most useful, because they showed how the authors' methods had evolved over time, with actual Zettelkasten use. This is much better than the kind of breathless article that says, basically: “I heard about this Zettelkasten word two days ago and now I’m up against a deadline to post something, anything.” The HN comments are worth skimming too, not least because there are a some sensible criticisms of this system and plenty of alternative suggestions.

To be honest, though, I’ve found the commentary on Reddit and at the zettelkasten.de forum to be generally of a higher quality. This is probably because the participants there are all already Zettelkasten-curious.

More than ever, embracing your humanity is the way forward.

Innovation makes people panic.

Every so often there’s a panic about how the computers are making us look bad.

I first experienced this as a kid when pocket calculators came out and maths teachers everywhere spent several years trying to stop us from using them.

But there had already been many previous rounds of this tech-induced disorientation. When telephones went mainstream, the morse code operators were probably saying, “Well the voice is all very well but it can hardly match the speed and precision of dots and dashes, so my job is clearly quite safe. or is it?”

And this is not to mention that the morse operators had already put the semaphore operators out of a job.

More recently people freaked out about personal computers, spreadsheets, word processors, robots that built cars, robots that built robots, mobile phones, smart phones, chess computers, Go computers. The list goes on and on.

The latest entry is, of course, AI, or to be more exact, large language models (LLMs) that produce automated text, and their image-creating, deep learning equivalents. Midjourney and DALL-E are quickly killing off artists' livelihoods. Meanwhile, ChatGPT makes it look as though technical writers and copywriters are doomed to retraining.

Promethean shame

Each of these moments of innovation involves an emotion similar to what German philosopher Günther Anders called ‘Promethean shame’. This is the feeling that technology is embarrassing us by pointing out our human limitations. We’re just not as good at doing things as the tech that we invented to ‘help’ us do it. In Anders' original formulation the shame arose in the observation of high quality manufactured goods. What was it shame of? That we were born, not manufactured (Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen, 1956). In the face of the latest AI panic, we’re asking, yet again: if the tools don’t really need us, what’s the point of humans at all?

Naval said, “nobody can compete with you on being you."

This is true, but being you, last time I looked, doesn’t pay the rent. This is why Promethean shame is so powerful. It’s associated with the real prospect of destitution.

This type of shame really plays to our fears of being thrown on the scrap heap. As Anders observed:

“The modern individual is not afraid of being used (employed, exploited), but of not being used (p. 42)”

Gold medals for effort

Actual humans aren’t good at much. And Promethean shame means they’re even embarrassed to be themselves. Most of the time, we ignore our limitations and celebrate our supposedly amazing prowess. What are the Olympic Games, for example, other than a sad display of how humans without powered accessories are really quite slow, and can’t even jump as high as a ladder? But no one ever mentions this embarrassing fact. To do so would obviously be tasteless. Instead we marvel at a human achieving a triple spin when the best previous attempt was two and a half spins. We’re collectively wowed by a person swimming almost as fast as a slow rowing boat, or rowing almost as fast as a broken speed boat. They hand out gold medals for effort.

When general knowledge genius Ken Jennings lost the TV game show Jeopardy! against a computer named Watson, he wrote an article about the experience called My puny human brain.

One reason we find it difficult and embarrassing to accept that we’re worse than our machinery is that we already tended to discount the sub-par people. The poor, the disabled, the maimed, the troubled, the difficult, the different in, oh, so many ways. The culture already looked down on all of them, tried to silence them and make them less visible. We already knew that some people didn’t make the cut. They were too old, too young, too sick, too foreign, or not foreign enough. Well, now that’s us. All of us.

The solution to Promethean shame is to recognise it, then to lean into our humanity. No one is as good at being human as an actual human. And to be human means to be fragile, frail and fallible. And it’s a hallmark of genuine human being that we’re just not that great. Paradoxically, this means the better a fake human (robot, chatbot, talking iron, whatever) becomes at imitating a human, the worse it will be at replacing the actual humans.

Mediocre is good enough - for some

We used to get paid to produce work that was ‘good enough’, but now computers can do it faster and for peanuts. And does anyone really care if it’s mediocre? That has yet to be seen.

William Deresiewicz observed:

“having turned art into “content”—limitless, interchangeable, disposable—the internet has already eroded taste to such an extent that fewer and fewer people are capable of distinguishing between crap and quality in the first place. Or bother to.”

Indeed, it’s now possible for AI publishers like Ingenio to churn out, say, 10,000 celebrity horoscope profiles a month. And if it turns out there’s a viable business model for this kind of flood it will just be a confirmation of TV producer Dan Harmon’s prediction from way back in 2016:

“maybe everyone in the world will turn out to be so hopelessly stupid that they think bad things are good”.

Thriving on the new normal

Harmon’s advice to those with writer’s block was to admit that your writing is terrible and do it anyway. Except that his version was cruder:

“Switch from team “I will one day write something good” to team “I have no choice but to write a piece of shit””.

As it happens this is the human condition. Ernest Hemingway once told F. Scott Fitzgerald:

“I write one page of masterpiece to ninety one pages of shit.”

If mostly failing was good enough for Hemingway, it’s probably good enough for you. And this is good general advice for the new age of AI. As humans, we suck so we might as well get used to it 1. In any case, this is what we’ve been getting used to for generations now. We can’t stand the cold so we wear clothes. And to stop our dangerously soft feet from wearing out we wear shoes. We can’t run at 80 or even 50 kilometres per hour so we drive cars. We can’t shout across oceans so we send email.

The sentence we find ourselves needing to complete now is: We can’t each produce 10,000 romance novels per month, so we…”

Austin Kleon points out that after Ken Jennings lost out to Watson on Jeopardy! that wasn’t the end of his story. He now makes a living being the person who lost to a computer. He’s a professional human loser.

That’s what we all are now. And it’s really nothing to be ashamed of.

I’m not saying everything is fine in the world of AI, and there’s nothing to worry about. There are larger questions of capitalist extraction and exploitation. And these won’t be addressed merely by regulating the tech multinationals. Meanwhile, though, let’s at least recognise we’re just humans. All of us.

References

Anders, Günther. 2016. On Promethean Shame. In Prometheanism: Technology, Digital Culture and Human Obsolescence, Christopher John Müller, 29-95. London: Rowman & Littlefield International.

Fuchs, Christian. 2017. Günther Anders’ Undiscovered Critical Theory of Technology in the Age of Big Data Capitalism. Triple C Vol 15 No 2.

-

A counterpoint to Stewart Brand’s programmatic claim in the first edition of his Whole Earth Catalogue (1968), “We are as gods and might as well get good at it.” ↩︎

🍳📷 I made this. Just saying.

📷🐦Though they’re a common site on Sydney Harbour and the Parramatta River, I rarely see this many cormorants gathered together. Guessing there must be a lot of fish in these bays. TIL an alternative collective term for a flock of cormorants is a gulp.

Aby Warburg's Zettelkasten and the search for interconnection

Aby Warburg and the compulsion to interconnect

Aby Warburg was a German art historian obsessed with the connections he saw across European and Mediterranean culture in the afterlife of Antiquity. He even coined a phrase: Verknüpfungszwang - the compulsion to find connections.

“Coining a word that is as fitting as it is symptomatic of the urge it describes, [Aby] Warburg spoke of his Verknüpfungszwang. This ‘compulsion to interconnect’ lies not only at the root of his research and working methods. It is also manifested in regular references within his work to events in his private life, his family and collaborators.” - The Warburg Institute

Three projects in particular display Warburg’s extraordinary scholarly methods.

“The library, panels and boxes formed the ensemble of supports on which Aby Warburg’s spiritual work and intellectual creativity were based.” - Benjamin Steiner, Aby Warburgs Zettelkasten Nr. 2 “Geschichtsauffassung”, In: Heike Gfrereis / Ellen Strittmatter (Hrsg.): Zettelkästen. Maschinen der Phantasie (Marbacher Kataloge, 66). Marbach 2013, S. 154-161.

Taken together, these three amount to a technology for exploring Warburg’s obsession with interconnection.

Image source: Helix Center Warburg Symposium

The Zettelkasten as a thread through the labyrinth of thought

The first technology of note is Warburg’s Zettelkasten, his collection of index boxes, containing notes on many subjects.

“Aby Warburg’s collection of index cards (III.2.1.ZK), containing notes, bibliographical references, printed material and letters, was compiled throughout the scholar’s life. Ninety-six boxes survive, each containing between 200 and 800 individually numbered index cards. Cardboard dividers and envelopes group these index cards into thematic sections. The online catalogue reproduces the structure of the dividers and sub-dividers with their original titles in German and consists of about 3,200 items.” - Warburg Institute Archive

“…Warburg apparently worked constantly with these boxes, and, as his first biographer Carl Georg Heise has reported, he often stood with a strained facial expression bent over the mass of papers and arranged and shifted the individual cards in a long-lasting and never-ending process of order. “Those who follow Warburg’s note box follow his train of thought; from the banking system in Florence, the medieval trading company, the development of individuality, the restless professional work of the Calvinists and the Reformed form of asceticism, to Warburg’s own origin from the old Jewish banking family. The slip box is Warburg’s Ariadne’s thread through his labyrinthine library like his labyrinthine thinking: from the werewolf to the historical concept. A thought, an idea or a new concept does not emerge in a linear progression, but in a process of reciprocating units of ideas and cross-references, which continues until new intersections and nodes have formed.” - Benjamin Steiner, Aby Warburgs Zettelkasten Nr. 2 “Geschichtsauffassung”, In: Heike Gfrereis / Ellen Strittmatter (Hrsg.): Zettelkästen. Maschinen der Phantasie (Marbacher Kataloge, 66). Marbach 2013, S. 154-161.

According to Fritz Saxl, Warburg’s assistant and collaborator, “this vast card-index had a special quality… they had become part of his system and scholarly existence”.

“Often one saw Warburg standing tired and distressed bent over his boxes with a packet of index cards, trying to find for each one the best place within the system; it looked like a waste of energy. […] It took some time to realise that his aim was not bibliographical. This was his method of defining the limits and contents of his scholarly world and the experience gained here became decisive in selecting books for the Library.” - Fritz Saxl, The History of Warburg’s Library (1943-44, p. 329), quoted in Mnemonics, Mneme And Mnemosyne. Aby Warburg’s Theory Of Memory, Claudia Wedepohl (p.389).

A library of good neighbours

Second of note, and much larger than the card-index, is Warburg’s library. As the oldest son, Aby Warburg was in line to inherit his family’s seriously wealthy banking business. But his lack of interest in finance led him to offer the business to his younger brother Max, on the condition he could purchase any books he needed for his research into his true interest, art history. It may have seemed like a modest request, but Warburg’s book collection grew ever larger and eventually expanded into a significant research library. This library was organised like no other. The shelves, and eventually whole rooms were arranged to enable serendipitous connections across and between categories.

“the book you need might not necessarily be the one you were looking for. It might, in fact, be the one next to it. The books are shelved around the law of the good neighbour, meaning that the library’s collection is organised thematically instead of by author, title, or publication date. Gertrud Bing, an architect of the classification system and director of the Institute when it moved to London, said that ‘the manner of shelving the books is meant to impact certain suggestions to the reader who, looking on the shelves for one book, is attracted by the kindred ones next to it, glances at the sections above and below, and finds himself involved in a new trend of thought which may lend additional interest to the one he was pursuing’. Although the Warburg’s serendipitous system may initially seem unconventional and somewhat esoteric, the structuring of the library’s collection around the law of the good neighbour means that it is much easier for readers to discover and find texts they didn’t even know they needed within the interconnected, interdisciplinary classmarks. For Warburg, every book was useful in the context of the whole collection.”

…“the arrangement of the books at the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, the first Warburg library in Hamburg, was intended to encourage rather than obstruct discoveries. Whenever Warburg, an avid book collector, took receipt of one of his many deliveries of new acquisitions, he would rearrange the shelves to accommodate each new book into the collection. In this way, his theories on the interrelation of various images, literary motifs and disciplines found physical form in the arrangement of the books on the shelves. Bing remarked that ‘Warburg had chosen and arranged the books like stones from a mosaic of which he had the pattern in his mind’. They were collected for research into specific areas, under a general theme of the afterlife of antiquity.” Source: The Warburg Institute

An Atlas of Images

The third technology for making connections was Warburg’s visual Memosyne Atlas, intended to demonstrate in a series of large panels the lines of connection between artistic motifs in varying periods and locations.

“Warburg believed that these symbolic images, when juxtaposed and then placed in sequence, could foster immediate, synoptic insights into the afterlife of pathos-charged images depicting what he dubbed “bewegtes Leben” (life in motion or animated life).” - ZKM Center for Art and Media

Warburg’s institutional legacy

These three enterprises, card index, library and atlas, are today combined into the Warburg Institute, which began life in Hamburg and since 1944 has been in London.

Above the front door of the Institute is inscribed the Greek word MEMOSYNE. Warburg saw this not straightforwardly as the name of the goddess of memory, but as a sphynx presenting a great riddle. The Institute revolves around memory as a problem. What is memory? How does it persist in culture and individuals, and especially through art?

“In the first public occurrence of the word “Mnemosyne” I am aware of in his writings, found in the annual report on the Library for the year 1925, Warburg identifies Mnemosyne not as the goddess of Memory and mother of the Muses but rather as “the great Sphynx,” out of whom he hopes “to unlock, if not her secret, at least the formulation of her riddle [der grossen Sphynx Mnemosyne, wenn auch nicht ihr Geheimnis, so doch die Formulierung ihrer Rätselfrage zu entlocken]”” – Davide Stimilli, «Aby Warburg’s Impresa», Images Re-vues (En ligne), Hors-série 4, 2013.

Arguably, Warburg’s self-diagnosed Verknüpfungszwang, his ‘compulsion to interconnect’ hindered the completion and publication of his work. Perhaps his constant sorting and re-sorting represented a kind of perfectionism, or even a form of obsessive-compulsive behaviour. Indeed, he spent several years battling significant mental health problems and the end published comparatively little.

However, in another sense, through his Zettelkasten, his library and his atlas of images, the compulsion to interconnect became Warburg’s life’s work. It is telling that though Warburg left relatively few completed texts, his institutional legacy, especially through London’s Warburg Institute and Hamburg’s Warburg-Haus, has proved extremely influential and highly intellectually fertile over many decades - and continues strongly into the Twenty-first Century.

In his novel The White Castle (1998), Orhan Pamuk’s narrator says: “I suppose that to see everything as connected with everything else is the addiction of our time.” The life and legacy of Aby Warburg, shows that this doesn’t have to be a pointless pursuit of arbitrary links but can generate lasting knowledge and meaning with wide implications.

Further reading and viewing:

Chernow, Ron (1993). The Warburgs: The Twentieth Century Odyssey of a Remarkable Jewish Family. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0525431831.

The Warburg Institute Library: A Brief Description

Introduction to the Warburg Institute Library and Collections - description of Warburg’s Zettelkasten at 8:36

Aby Warburg: Metamorphosis and Memory - and Chris Aldridge’s online notes on this documentary (which is how I discovered it).

I’m the author of Shu Ha Ri. The Japanese Way of Learning, for Artists and Fighters, available now in paperback and ebook.

Thanks to a post by @chrisaldrich I was finally prompted to write about Aby Warburg’s Zettelkasten and library.

Aby Warburg's Zettelkasten and the search for interconnection writingslowly.com

Aby Warburg's Zettelkasten and the search for interconnection

Aby Warburg and the compulsion to interconnect

Aby Warburg was a German art historian obsessed with the connections he saw across European and Mediterranean culture in the afterlife of Antiquity. He even coined a phrase: Verknüpfungszwang - the compulsion to find connections.

“Coining a word that is as fitting as it is symptomatic of the urge it describes, [Aby] Warburg spoke of his Verknüpfungszwang. This ‘compulsion to interconnect’ lies not only at the root of his research and working methods. It is also manifested in regular references within his work to events in his private life, his family and collaborators.” - The Warburg Institute

Three projects in particular display Warburg’s extraordinary scholarly methods.

“The library, panels and boxes formed the ensemble of supports on which Aby Warburg’s spiritual work and intellectual creativity were based.” - Benjamin Steiner, Aby Warburgs Zettelkasten Nr. 2 “Geschichtsauffassung”, In: Heike Gfrereis / Ellen Strittmatter (Hrsg.): Zettelkästen. Maschinen der Phantasie (Marbacher Kataloge, 66). Marbach 2013, S. 154-161.

Taken together, these three amount to a technology for exploring Warburg’s obsession with interconnection.

Image source: Helix Center Warburg Symposium

The Zettelkasten as a thread through the labyrinth of thought

The first technology of note is Warburg’s Zettelkasten, his collection of index boxes, containing notes on many subjects.

“Aby Warburg’s collection of index cards (III.2.1.ZK), containing notes, bibliographical references, printed material and letters, was compiled throughout the scholar’s life. Ninety-six boxes survive, each containing between 200 and 800 individually numbered index cards. Cardboard dividers and envelopes group these index cards into thematic sections. The online catalogue reproduces the structure of the dividers and sub-dividers with their original titles in German and consists of about 3,200 items.” - Warburg Institute Archive

“…Warburg apparently worked constantly with these boxes, and, as his first biographer Carl Georg Heise has reported, he often stood with a strained facial expression bent over the mass of papers and arranged and shifted the individual cards in a long-lasting and never-ending process of order. “Those who follow Warburg’s note box follow his train of thought; from the banking system in Florence, the medieval trading company, the development of individuality, the restless professional work of the Calvinists and the Reformed form of asceticism, to Warburg’s own origin from the old Jewish banking family. The slip box is Warburg’s Ariadne’s thread through his labyrinthine library like his labyrinthine thinking: from the werewolf to the historical concept. A thought, an idea or a new concept does not emerge in a linear progression, but in a process of reciprocating units of ideas and cross-references, which continues until new intersections and nodes have formed.” - Benjamin Steiner, Aby Warburgs Zettelkasten Nr. 2 “Geschichtsauffassung”, In: Heike Gfrereis / Ellen Strittmatter (Hrsg.): Zettelkästen. Maschinen der Phantasie (Marbacher Kataloge, 66). Marbach 2013, S. 154-161.

According to Fritz Saxl, Warburg’s assistant and collaborator, “this vast card-index had a special quality… they had become part of his system and scholarly existence”.

“Often one saw Warburg standing tired and distressed bent over his boxes with a packet of index cards, trying to find for each one the best place within the system; it looked like a waste of energy. […] It took some time to realise that his aim was not bibliographical. This was his method of defining the limits and contents of his scholarly world and the experience gained here became decisive in selecting books for the Library.” - Fritz Saxl, The History of Warburg’s Library (1943-44, p. 329), quoted in Mnemonics, Mneme And Mnemosyne. Aby Warburg’s Theory Of Memory, Claudia Wedepohl (p.389).

A library of good neighbours

Second of note, and much larger than the card-index, is Warburg’s library. As the oldest son, Aby Warburg was in line to inherit his family’s seriously wealthy banking business. But his lack of interest in finance led him to offer the business to his younger brother Max, on the condition he could purchase any books he needed for his research into his true interest, art history. It may have seemed like a modest request, but Warburg’s book collection grew ever larger and eventually expanded into a significant research library. This library was organised like no other. The shelves, and eventually whole rooms were arranged to enable serendipitous connections across and between categories.

“the book you need might not necessarily be the one you were looking for. It might, in fact, be the one next to it. The books are shelved around the law of the good neighbour, meaning that the library’s collection is organised thematically instead of by author, title, or publication date. Gertrud Bing, an architect of the classification system and director of the Institute when it moved to London, said that ‘the manner of shelving the books is meant to impact certain suggestions to the reader who, looking on the shelves for one book, is attracted by the kindred ones next to it, glances at the sections above and below, and finds himself involved in a new trend of thought which may lend additional interest to the one he was pursuing’. Although the Warburg’s serendipitous system may initially seem unconventional and somewhat esoteric, the structuring of the library’s collection around the law of the good neighbour means that it is much easier for readers to discover and find texts they didn’t even know they needed within the interconnected, interdisciplinary classmarks. For Warburg, every book was useful in the context of the whole collection.”

…“the arrangement of the books at the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, the first Warburg library in Hamburg, was intended to encourage rather than obstruct discoveries. Whenever Warburg, an avid book collector, took receipt of one of his many deliveries of new acquisitions, he would rearrange the shelves to accommodate each new book into the collection. In this way, his theories on the interrelation of various images, literary motifs and disciplines found physical form in the arrangement of the books on the shelves. Bing remarked that ‘Warburg had chosen and arranged the books like stones from a mosaic of which he had the pattern in his mind’. They were collected for research into specific areas, under a general theme of the afterlife of antiquity.” Source: The Warburg Institute

An Atlas of Images

The third technology for making connections was Warburg’s visual Memosyne Atlas, intended to demonstrate in a series of large panels the lines of connection between artistic motifs in varying periods and locations.

“Warburg believed that these symbolic images, when juxtaposed and then placed in sequence, could foster immediate, synoptic insights into the afterlife of pathos-charged images depicting what he dubbed “bewegtes Leben” (life in motion or animated life).” - ZKM Center for Art and Media

Warburg’s institutional legacy

These three enterprises, card index, library and atlas, are today combined into the Warburg Institute, which began life in Hamburg and since 1944 has been in London.

Above the front door of the Institute is inscribed the Greek word MEMOSYNE. Warburg saw this not straightforwardly as the name of the goddess of memory, but as a sphynx presenting a great riddle. The Institute revolves around memory as a problem. What is memory? How does it persist in culture and individuals, and especially through art?

“In the first public occurrence of the word “Mnemosyne” I am aware of in his writings, found in the annual report on the Library for the year 1925, Warburg identifies Mnemosyne not as the goddess of Memory and mother of the Muses but rather as “the great Sphynx,” out of whom he hopes “to unlock, if not her secret, at least the formulation of her riddle [der grossen Sphynx Mnemosyne, wenn auch nicht ihr Geheimnis, so doch die Formulierung ihrer Rätselfrage zu entlocken]”” – Davide Stimilli, «Aby Warburg’s Impresa», Images Re-vues (En ligne), Hors-série 4, 2013.

Arguably, Warburg’s self-diagnosed Verknüpfungszwang, his ‘compulsion to interconnect’ hindered the completion and publication of his work. Perhaps his constant sorting and re-sorting represented a kind of perfectionism, or even a form of obsessive-compulsive behaviour. Indeed, he spent several years battling significant mental health problems and the end published comparatively little.

However, in another sense, through his Zettelkasten, his library and his atlas of images, the compulsion to interconnect became Warburg’s life’s work. It is telling that though Warburg left relatively few completed texts, his institutional legacy, especially through London’s Warburg Institute and Hamburg’s Warburg-Haus, has proved extremely influential and highly intellectually fertile over many decades - and continues strongly into the Twenty-first Century.

In his novel The White Castle (1998), Orhan Pamuk’s narrator says: “I suppose that to see everything as connected with everything else is the addiction of our time.” The life and legacy of Aby Warburg, shows that this doesn’t have to be a pointless pursuit of arbitrary links but can generate lasting knowledge and meaning with wide implications.

Further reading and viewing:

Chernow, Ron (1993). The Warburgs: The Twentieth Century Odyssey of a Remarkable Jewish Family. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0525431831.

The Warburg Institute Library: A Brief Description

Introduction to the Warburg Institute Library and Collections - description of Warburg’s Zettelkasten at 8:36

Aby Warburg: Metamorphosis and Memory - and Chris Aldridge’s online notes on this documentary (which is how I discovered it).

Emotional Ignorance by Dean Burnett 📚demolishes the old myth that we only use 10% of our brains. It’s far more complex and interesting than that. My brain is literally parked outside for all but 5% of the time. Yet when I need to go somewhere I need 100% of it. So inefficient! Wait, that’s my car.

Was Dracula foiled by a gang of obsessive note-takers?

May 3 is the date Bram Stoker’s famous novel, Dracula begins. It’s a classic tale of evil, lust and violence and you can follow along from the safety of your in-box with Dracula Daily.1

I was not able to light on any map or work giving the exact locality of the Castle Dracula, as there are no maps of this country as yet to compare with our own Ordnance Survey maps; but I found that Bistritz, the post town named by Count Dracula, is a fairly well-known place. I shall enter here some of my notes, as they may refresh my memory when I talk over my travels with Mina.

The novel is presented as a whole series of notes - journal entries, letters, typed memos and phonograph transcriptions - by a group of bewildered friends (lovers? enemies?), as they try to make sense of the supernatural designs of the mysterious Count. In 1897, when the novel was written, all this seemed new and high-tech. The story, in effect, pits aspirational note-taking against monstrous, blood-sucking evil. You’ll have to read it to find out which of these two tremendous powers wins out in the end.

These days, fortunately, all we have to worry about is ChatGPT taking our jobs. But collecting our notes together and making sense of them, against all the odds, remains as important as ever.

-

I have no connection with this site - I’m just obsessed with Dracula. ↩︎

30 years of the World Wide Web. An incredible journey! I recall wondering if it would supersede Gopher. Didn’t have to wonder long. I also remember CompuServe pretending the WWW didn’t exist. That didn’t last long either. www.npr.org/2023/04/3…

More discontent in the world of academic publishing. It’s amazing how far the brightest people have been tricked by the industry. Troubling to see how hard is their climb back out of the well. dailynous.com/2023/04/2…

“The question: what are you making with your notes?” An important question, and a great article from @annahavron

“Everyone needs their own thinking space.” Sometimes it’s a room of your own, sometimes it’s a website of your own. But it’s never Chad’s Garage - because Chad’s garage is not yours.

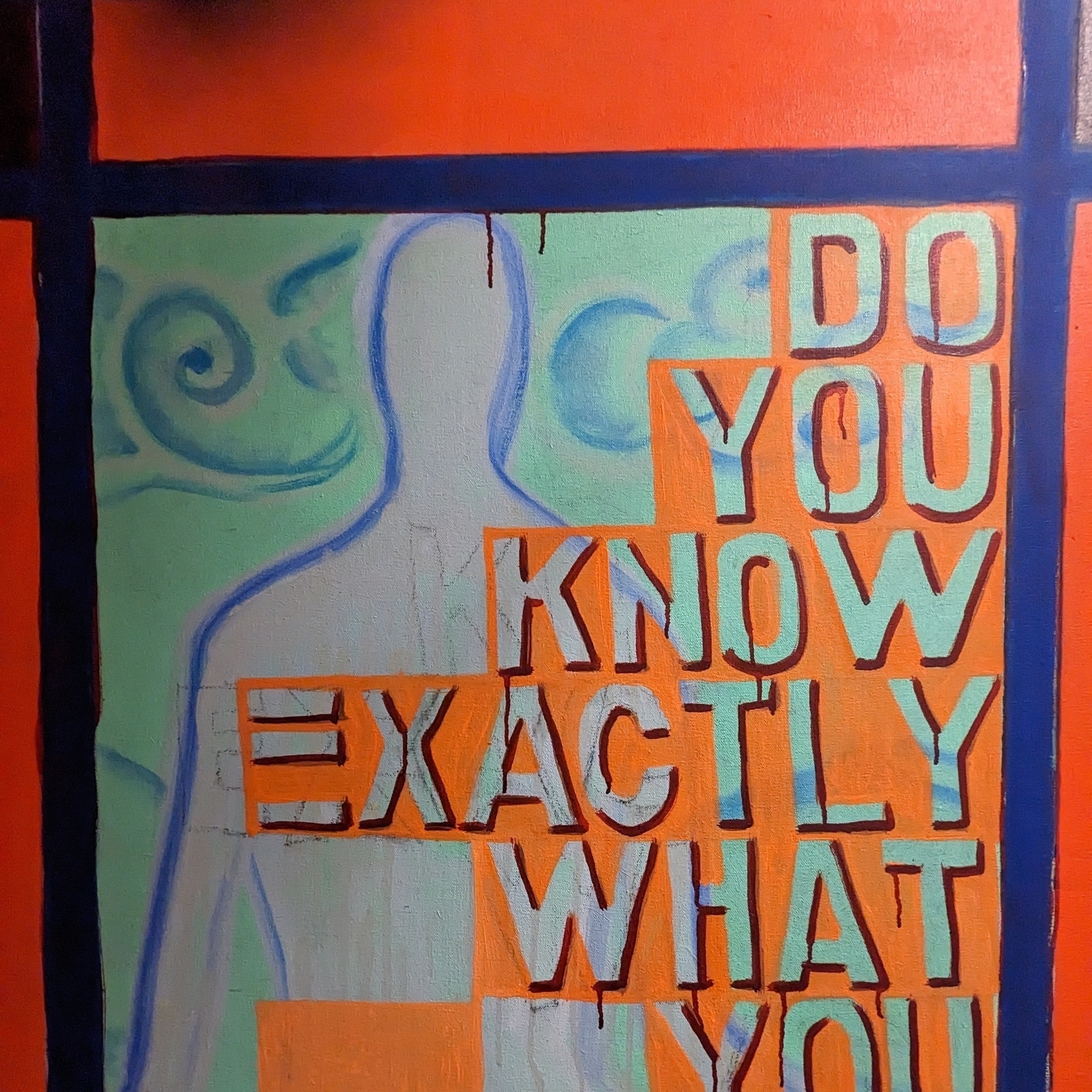

“Do you know exactly what you want?” It’s a very good question. I do, and my word of the year is “focus”. That’s because I find it very hard to prioritise what I want. I suspect I’m not alone in this

An amazing Femi Kuti concert last night. The recordings are great but they don’t do justice to this band in person. The total confidence that everyone in the audience would be dancing and the complete fulfilment of that confidence.

For two enthralling hours of Afrobeat Femi Kuti gave more energy than all his dancers put together - and they gave a huge amount of energy.

There was a sax solo from Femi that was completely magical. I wouldn’t previously have called myself a fan but I was completely won over. It was a sublime night. Live music at its absolute best. 🎵

📷 Golden early-evening light on the route home.

The Writer’s Journey began as a memo.

Working at Disney during the 1980s, Christopher Vogler saw senior executives using memos effectively. He wrote one to summarise The Hero with a Thousand Faces, as he was sure Joseph Campbell’s book had inspired George Lucas’s Star Wars. He wrote a 7-page memo that became so popular he expanded it into a book. This became the ‘Bible’ for beginning scriptwriters. He called it a ‘practical guide’, since besides summarising Campbell’s ideas on narrative, he showed how they could be used to write film scripts.

Question: what else could start with just a memo?

April already

📷📚It’s April already. Do the months slip past ever faster?

Autumn has arrived again and it’s glorious - a limpid blue sky after a weekend wet with rain. Quite different from Summer, when we would push open the rear doors to enjoy the cooling breezes from the coast, and watch dragonflies come and go as they pleased.

But Autumn is the season when our kitchen comes into its own. Through closed windows the early morning sun warms the room, inviting us to attend, to sit and read. That’s why we’ve moved the rocking chair back to its corner in the light.